Tom Selleck is faced with a dilemma. He is being forced to make a decision that will annoy at least one of three people.

“Well, I don’t know, Esme. What do you think?”

His publicist, Esme Chandlee, who is seated beside Selleck on a sofa in his office at Universal Studios, folds her arms and says, “If it’s what you want, Thomas!”

“We could maybe try it, Esme,” Selleck says.

“I don’t know why,” she says. “I’m not bothering anyone.”

Selleck looks beseechingly at me. “What do you think? Esme really hasn’t interfered.”

“It inhibits me,” I say. “I’ve never interviewed someone with their publicist sitting in.”

Selleck now looks beseechingly at Chandlee. “Gee, I feel comfortable with him, Esme. Maybe we could try it. Just him and me.” Chandlee stands up and glares at me. Selleck adds quickly, “If you don’t mind?”

“All right, Thomas,” she says. “If that’s the way you want it! But give him just ten more minutes. Do you hear Thomas?” Selleck nods like a chastised youngster as Chandlee leaves the room.

“Gee, l hope I didn’t offend her,” he says. “That’s the way she’s always done it with me.”

Esme Chandlee is in her late sixties. A savvy, schoolmarmish woman with rust-colored hair. She has been a Hollywood publicist for more than thirty years. She remembers Ava Gardner as a teenager in a halter top and tight shorts. “She breezed into the studio without makeup or shoes,” says Chandlee, “and every head turned.”

That was a time in Hollywood when actors were not actors, but stars. The stars deferred to their publicists, who kept a tight rein on their careers and lives. They built their stars’ careers less upon acting talent than on a distinctive, unwavering persona that satisfied their fans’ needs. These fans went to the movies to see John Wayne play John Wayne, not some fictional character.

It was also the publicist’s job to make sure that the John Wayne seen in the movies was consistent with the John Wayne seen in the press. Publicists often selected the magazines their stars would appear in, even setting the scene where an interview would take place (“Thomas will take batting practice with the Dodgers this afternoon,” says Chandlee. “You can watch”) and writing the script (“Tom always hits a few home runs in batting practice,” she adds). When the scene didn’t quite play as written (Selleck swings through the first twenty pitches thrown him, hangs his head and says, “This is humiliating!”), they simply stuck to their script (“Thomas! What are you talking about? You hit some good ones.”).

“In films, you can get a career-ending momentum from one film,” he says. Which is why movie actors make themselves accessible to the press: to keep their public presence alive in between screen appearances.

They also determined the questions to be asked and not asked, and just to make sure their rules were followed, they sat in on each interview, nodding, smiling, frowning, pointing a long finger at the reporter’s notebook (“Come on! Come on! We don’t have all day!” says Chandlee) and even, on occasion, interrupted their star with a clarification (“l don’t think Tom said he was opposed to abortion. Did you Thomas?”).

Most of Esme Chandlee’s stars are now dead, like John Cassavetes, or semiretired, like Vera Miles. She still has Selleck, though, and, to a lesser extent, Sam Elliott. Her boys. She fusses over their careers, both of which were based more on masculine images than on acting ability and were established in television rather than in feature films. Television is the last bastion of the old star system. Careers are founded there—stars are made there—by forging a captivating persona that never wavers from week to week. TV stars are so closely identified with their characters (Magnum, Rockford, J.R., Alexis) that fans often refer to them by those names.

Which is fine for TV stars as long as they remain on TV, as Tom Selleck did with Magnum, P.I. for eight years. But Magnum is gone now, at Selleck’s request, and he is trying to build a film career from his new home near L.A.

“L.A. has changed a lot in the eight years I was in Hawaii,” says Selleck. “L.A. jokes are more valid now. There are a lot more people full of shit here. I don’t mean to get into L.A.-bashing, but I was lucky to be isolated in Hawaii. It was the most wonderful experience of my life. I just worked.”

As a TV actor in the hinterland, Selleck was removed from the pressures and critical scrutiny of Hollywood. Television also afforded him the luxury of not needing the press, since his face appeared onscreen weekly rather than in a movie once a year. “In films, you can get a career-ending momentum from one film,” he says. Which is why movie actors make themselves accessible to the press: to keep their public presence alive in between screen appearances. Now that Selleck is solely doing films, he finds himself in the same position. “It’s new to me,” he says. “In-depth interviews. I don’t know how to do them yet.”

Selleck’s success in film has been limited. Of his nine movies, only Three Men and a Baby, in which he shared the spotlight with Ted Danson and Steve Guttenherg, was a critical and financial hit. Much of the criticism leveled at the failures (Her Alibi, Lassiter, Runaway, High Road to China) centered upon Selleck’s insistence on playing himself, or, rather, the self he had created with Magnum. Amiable. Jocky. Bumbling. Insecure. Unthreatening (to men and women). And disbelieving of his very substantial physical charms.

The problem is that Selleck’s characters in Lassiter and High Road were each supposed to have had a certain hard edge: In High Road, for instance, Patrick O’Malley was a drunken, conniving mercenary who exploits women in a way not dissimilar to that of Burt Reynolds’s film persona. (Burt and Tom are good friends. Selleck is listed as executive producer of Reynolds’s ABC-TV series, B. L. Stryker, and he is probably the only actor alive who will lower his eyes modestly and say “Thank you” when compared to Reynolds as an actor.) But Selleck didn’t totally mask his Magnum amiability in those roles. Like Reynolds, Selleck is of the acting school that insists that no matter what character he portrays onscreen, he must never let the audience forget the image he has off-screen. “I think it’s a compliment if the audience only sees me,” he says.

It just goes against Selleck’s nature not to be amiable. “I don’t see any reason not to be nice,” he says. “It can be one way, and an effective one, of achieving certain ends. Still, it bothers me when people equate niceness with being dull and wishy-washy. It makes me sound like a wuss.”

Even the success of Three Men and a Baby was predicated on his playing … an amiable, bumbling, love-struck architect—the one twist being that rather than a 25-year-old female in a bikini his love interest was a 6-month-old female in diapers.

The Boston Globe once wrote that Selleck was the only actor who appeared big on the small screen and small on the big screen. Actors who get away with playing the same character type in movie after movie (Mel Gibson, Clint Eastwood, Sylvester Stallone, Harrison Ford) do so because they have developed compelling personas that are bigger than life, which is what moviegoers demand. More intense, passionate, mysterious, heroic, screwy, even threatening. It was precisely Ford’s nutty quirks that elevated the seemingly normal professor into the obsessed adventurer Indiana Jones. Selleck, originally offered that part, had to turn it down because of Magnum commitments.)

Tom Selleck’s dilemma, then, is obvious. How far would he distance himself from Magnum—at the risk of losing his fans—in order to succeed in film?

But Tom Selleck is mercilessly normal, either unable or unwilling to take the risk not to be. For a human being, that’s admirable. For an actor, it can be fatal. TV viewers are drawn to the normal for their heroes (Selleck/Magnum, Cosby/Huxtable) because it reassures them about their own everyday lives. TV heroes are comforting because they are not bigger than life, which is why TV actors often have difficulty taking the leap to film. Those who do either create memorable characters, like Eastwood’s “Dirty Harry,” or simply learn how to act, like Steve McQueen and James Garner.

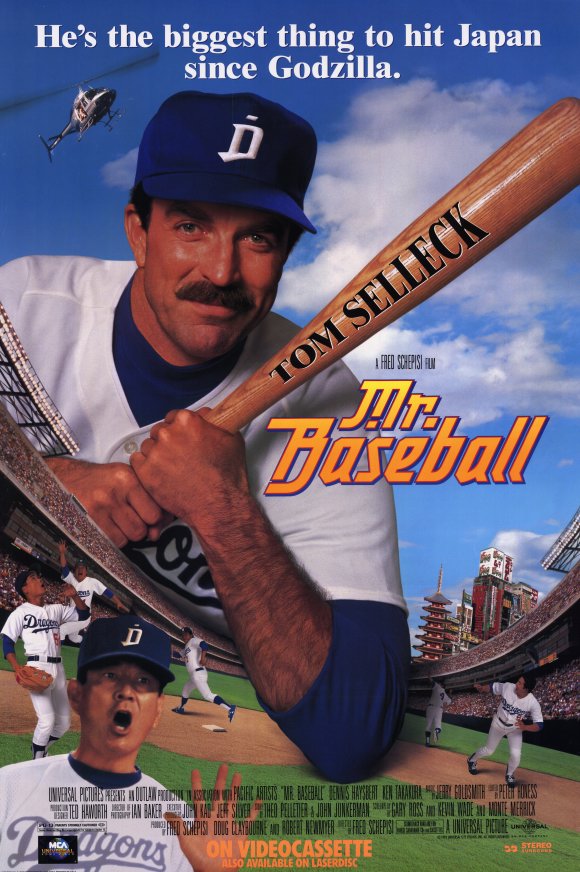

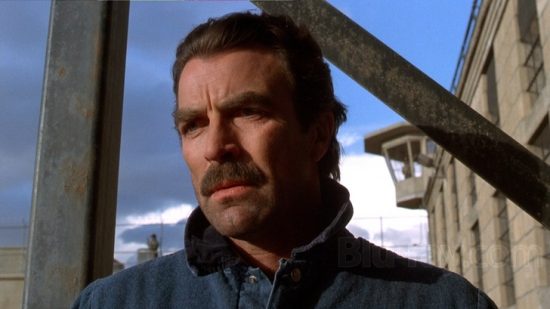

In his new movie, An Innocent Man, Selleck is still playing “normal,” an ordinary guy wrongly accused and imprisoned for a crime he didn’t commit.

“As an actor, Tom’s underrated,” says Bess Armstrong, his costar in High Road to China. “l don’t feel the material he’s chosen is up to his ability. I believe there’s a lot of potential there that hasn’t been tapped. Maybe he’s biding his time. Tom is aware of every step, aware of staying in power. He’s very savvy. Tom always has a plan.”

Tom Selleck’s dilemma, then, is obvious. How far would he distance himself from Magnum—at the risk of losing his fans—in order to succeed in film? Rather than make that painful decision, Selleck is doing what he usually does. He is trying to maintain a precarious balance.

“My biggest fear,” he says, “is not to be wanted. I don’t know if I’ll want to act in five or ten years, but I’d really like for people to want me to work. You can be loyal to your fans without pandering to them. But you also can’t take them for granted. I’ve always felt it was easier to get women fans than men. But you have to have the guys to be successful. I’ve never liked guys who pandered to women fans.”

Many women swoon over Selleck/Magnum’s good looks and nonthreatening sensitivity, while others echo the sentiments of one of his leading ladies, who says, “What was lacking for me was a certain messiness, a certain passion. Everything with Tom is in its box.” It was Magnum’s male viewers who made the show a success; they identified with Magnum’s flaws, not his strengths. It was significant that the red Ferrari he drove was his boss’s, not his own. What was even more significant was that Magnum’s pursuits of beautiful women more often than not ended in failure, just like those of his male viewers. Selleck sustained an eight-year TV run out of those weaknesses, ultimately earning almost $5 million a year, and he is loath to lose that career now.

“Every actor gets put in a box,” Selleck says. “It’s not a curse if you’re working. If it’s a small box, though, I don’t think you can buck it. I’d just like to make my box a little bigger. I try not to approach my career as if I’m some mythical personality; because that personality changes with people’s perceptions of it.

“I like to think that every film part of mine has been a stretch. I’m very happy with them. No matter how safe people thought my choices were, they were a big risk for me. I just have to balance those stretches with my limitations. I can’t ever play Quasimodo just to prove something, but I can push my parameters or else there will be a sameness to my work. I have to be willing to fail. You can’t have it both ways. Still, I can’t do a movie without thinking of my career. I wish I could, but I can’t. That’s the trap. When you start calling what you do ’a career,’ that’s when you start feeling the pressure.”

Selleck relies a lot on Chandlee to protect his career. He is loyal to her, he says, because she did a lot of free work for him thirteen years ago, when he was a struggling actor known more for his modeling (Salem cigarettes, Chaz cologne) than for his thespian exploits (he played a corpse in the film Coma). Selleck is ashamed of his modeling past and tries to distance himself from it by denigrating talk of his being a sex symbol. “I hate that!” he says. “I hate to work out with weights just to stay in shape. I never did like to throw it around. Too much muscle takes away from your character onscreen.”

Like many actors, Selleck is more than a little embarrassed by what he does for a living. He considers it unmanly. “It’s easy to stare someone down with a gun when you know that after they shoot you dead you can get up again. Now, a big left-handed pitcher throwing me curveballs, ouch! That’s real!”

Selleck, at six feet four, 210 pounds and 44 years of age, is proud of his athletic ability. He is an Olympic-caliber volleyball player and claims his greatest achievement was recently being named to an all-American team for men 35 to 45. He also likes to talk about his college basketball days, and how he could really leap. “l didn’t have white man’s disease,” he says. “In one episode of Magnum, we ended the show with me dunking a basketball. It was really important for me to do that without camera tricks.”

It’s important, too, for Selleck to take batting practice at least once a year with a major league team. He has done so with the Orioles (“l hit a few out at Memorial Stadium”) and with the Tigers (“A few players were screwing around in the outfield. When I hit one between them, they just looked.”) and, this past season, with the Dodgers. This time, it did not go well.

“You swing pretty good … for an actor.”

Selleck stood behind the batting cage with the pitchers, waiting to take his swings against the easy lobs of one of the team’s older coaches. The pitchers kidded around, occasionally including Selleck in their jokes. He laughed nervously. This was obviously an important moment for him. He had spent the previous day at a batting range in preparation and did not want to look foolish.

Steve Garvey, the former Dodgers first baseman, walked onto the field accompanied by his latest wife, a striking cotton-candy blonde. Garvey, dressed in a navy blazer and tan trousers, looked less like a ballplayer than an actor. One of the Dodgers said to another, “Who’s that with Garv?”

“His new wife.”

“How do you know?”

“She’s the one who’s not pregnant.”

Selleck went over to talk to Garvey. They chatted under a bright sun, two men who have embellished their careers by being “nice.” Finally, it was Selleck’s turn to hit. For the next hour he struggled, sweating and lunging, foul-tipping or just missing pitch after pitch. There was a lightness to his swing. He didn’t attack the ball, driving toward it with his shoulders, but swung only with his arms.

“You swing pretty good,” said one pitcher, “…for an actor.”

Selleck tried to smile.

When batting practice was over, Selleck heard a stern voice calling him from the seats behind home plate, “Thomas! Thomas!” He went over to Chandlee, who was seated alongside Selleck’s elder brother, Bob.

“That was humiliating!” Selleck said.

“Oh, Thomas!” Chandlee said. “That pitcher was throwing hard.”

“He was,” Selleck said. “Wasn’t he?”

“Pretty hard,” said Bob, who had been a pitcher in the Dodgers organization years ago. Bob is a boyishly tousled, Alan Alda sort of guy, who stands almost six feet six. Selleck is close to his brother, and to all of his family, whom he refers to as his best friends. He also has a younger brother and a sister; they, along with their father, Bob Sr., and mother, Martha, make a strikingly beautiful family. “Heads just turn when they all enter a room,” says Chandlee.

Born in Detroit, Selleck moved with his family to Sherman Oaks, California, when he was 4. His father was a real estate executive and president of the Little League. His mother was a den mother for the Cub Scouts and Brownies. There was a tradition in the family that if the children did not drink, smoke or swear until the age of 21, they would be given a gold watch. Selleck got his, although he claims he did lapse a few times.

Selleck excelled in sports and won a basketball scholarship to USC. He mostly sat on the bench, but when Pepsi was looking for a basketball player for an ad, he landed his first modeling job. He began pursuing acting after that, doing a little modeling on the side, until he received his draft notice. This was in 1967—the height of the Vietnam war. After taking his physical, Selleck was told that within three months he’d probably be sent overseas. Although Selleck “firmly believed in my military obligation,” he wanted to continue acting. So his father helped him get into the National Guard. He claims it was a very scary time to be in the Guard, given all the student riots across the country. Meanwhile, he appeared on the TV program The Dating Game twice. He wasn’t chosen either time, but he was noticed by executives at Twentieth Century Fox and given a studio contract. The rest is history. Salem. Chaz. Magnum. An Emmy. People’s Choice Award for favorite male TV performer, four times. A film price that is now in the millions. In 1986, his own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. And in August, a multi-picture deal with Disney similar to those of Bette Midler, Tom Hanks and Goldie Hawn.

It is not clear whether Selleck truly defers to Chandlee in decisions about his career or just wants to give the impression that he does. When Chandlee sits in on interviews, Selleck insists it’s her demand, not his. Yet when he did a Playboy interview some years ago, he told the reporter that a CBS publicist had to sit in because the network insisted. He didn’t want to offend them, Selleck said, because they had been so nice to him. Afterward, he called the writer a number of times to clarify a few points he had made. Selleck likes to make these personal follow-up calls. It’s his way of softening his various refusals to writers during interviews. No mention of his family. No talks with his wife. No visits to his home. No questions about his salary.

Such passive aggressiveness seems to be the way he conducts every facet of his life. “Eventually, I guess I got to know Tom,” says Laila Robins, who plays his wife in An Innocent Man. “I just didn’t feel he wanted to schmooze with me. I felt bad, because I’m a professional and know enough not to cross that personal line. He just didn’t trust me enough to let me not cross that line on my own. He always had people around to protect him, to serve as buffers. I’d go our to dinner with him and his makeup man and driver/bodyguard. I never felt they shut me out. It wasn’t that blatant. I just felt there was a point when he didn’t want to go that extra step.”

“Actors need buffers,” says Selleck. “We need people to say no for us.” Chandlee says no a lot for Selleck. It takes the burden off him so he won’t have to sully his image not being “nice.” Then, too, Tom Selleck is truly a “nice” man who does have trouble saying no to people. Even when he does, he will do it in a way that appears so painful for him, it doesn’t really seem like a no. Back in the late Seventies, as his marriage of ten years to Jacquelyn Ray was collapsing, he couldn’t bear to go through with the actual divorce for four years. “It’s one of the great sorrows of my life that we won’t be together,” he said at the time. “We’ve worked out an agreement to live separately, but we haven’t made any moves toward divorce.”

When Selleck goes out to dinner with his second wife, actress Jillie Mack (they’ve a 10-month-old daughter, Hannah Margaret Mack), he refuses to sign autographs while eating. But he takes great care to explain to his fans his reasons for saying, “Sometimes, it would just be easier to sign them,” he says. “Then when they left, I wouldn’t feel guilty.”

Selleck also felt guilty when he announced he was leaving Magnum after his seventh year. He felt he, personally, was pulling the plug on his crew’s careers. So he signed for an eighth and final season (at a considerable salary increase) just to give the crew one last big paycheck, and to give himself peace of mind.

Selleck loves to smoke cigars. “Obscenely large ones from Cuba,” he says. His favorite poem, by Rudyard Kipling, tells the story of a man forced to choose between the two great loves of his life: his fiancee, Maggie, and the beloved cigars Maggie demands that he give up. He wavers, debating the pros and cons of each love, until finally he makes his choice:

And a woman is only a woman, but a good cigar is a Smoke.

Light me another Cuba—I hold to my first-born vows,

If Maggie will have no rival, I’ll have no Maggie for Spouse!

It is ironic that Selleck’s favorite poem is about a man who makes a painful decision in a decisive way. Despite his own love of cigars, Selleck won’t smoke them in public for fear of offending his fans. When he is offered a cigar while seated in the crowded Dodgers bleachers, where no one has recognized him, he looks around quickly before saying, “I’d better not.”

In his political convictions, Selleck is equally equivocal, though they are of a conservative bent. He believes that socialism is a failed economic concept that limits wealth, while capitalism breeds it. “I benefit a lot of people by making a lot of money,” he says. “It doesn’t make me feel guilty. I can afford to be principled now because of my wealth. If you’re struggling with a family and you sell out, it’s understandable, but if you have wealth and you sell out, there’s something wrong.”

Selleck feels that women’s lib is “just an excuse for women to get even” and that abortion is not only a woman’s issue but a man’s, too. “It takes two people to have a baby,” he says. “And since there’s been no national consensus on it, one way or another, l don’t think the federal government should fund abortions. I would never encourage anyone to have an abortion, but you won’t see me pounding the streets one way or another about it. I don’t think I belong out there just because I did Magnum for eight years.”

The ultimate impression Selleck gives is of a man either physically unable to let himself go or of a man hiding some terrible secret. He’s the kind of guy who would probably be even nicer if he just stopped acting that way and let himself be naturally so.

Selleck also resents the fact that white Americans are often given the blanket label of racist, held responsible for sins committed 200 years ago. “I’m not responsible for slavery,” he says. “When that poor girl was raped in Central Park this year, Cardinal O’Connor said we were all responsible. I’m not. O’Connor said that God forgave those kids who raped the girl. God might have forgiven them, but I don’t think He forgave them right away.”

When Robert Bork was rejected by the Senate in his attempt to become a Supreme Court justice, Selleck thought it such an outrage that he sent a letter to each of the congressmen who had voted against Bork. Selleck never made that letter public, for the same reason he refuses to campaign for conservative political candidates. As he once said, “Flat out from a business point of view, I don’t think it’s a good idea to get involved. Yet at the same time you don’t want to compromise.”

It is the seventh inning of the game at Dodger Stadium, and Selleck has yet to be recognized as he sits in the home plate bleachers. It has been a rare treat for him to watch a game without fans assailing him for autographs. The last time he went to the stadium, he sat down below and was immediately spotted. He had to sign so many autographs that he never saw the game. He debated this time whether he should sit in the Stadium Club, where his privacy would be respected. But he rejected that possibility because looking through a glass partition is not like “really being at a game.”

“I’ve always been a private person in a public job,” he says now. “If I give all my privacy away to the public, I won’t have any left as an actor. I won’t have anything to show in my work. Still, I want to be able to do normal things, or else you get isolated and lose touch with reality. I miss all the rudimentary things other people do, like going to the beach and reading a book. I force myself to do these things sometimes, like this game. If I don’t, then privacy becomes the ability to lock yourself in your home, and you’ll never experience reality.”

Suddenly he stops talking and taps me on the shoulder. “Hey, look at that girl!” He points down below to a beautiful girl in a tight sweater returning to her seat behind home plate and whistles like a schoolboy. “That’s all right!” he says. There is something of the schoolboy about Selleck when he talks about women. He claims he is “painfully shy with girls“ and often had to be set up on blind dates. When he asked Jillie out for the first time, he sat in an upstairs bedroom, sweating and hesitating before finally mustering the nerve to dial her number. He was so tongue-tied that eventually she had to say, “Do you want to ask me out?”

“Gee, I hope she gets up again to go for popcorn,” Selleck says, still staring down at the girl. Then he catches himself. “Isn’t that silly?” Despite his adolescent ogling, Selleck is almost prudish about sex. When he’s told that one of his favorite actresses, Kim Basinger, gave a magazine interview recently in which she talked brazenly about wearing a see-through skirt without underwear, Selleck just shakes his head. “That’s too bad,” he says. When his brother Bob tells him an off-color joke that ends in oral sex between two men, Selleck slinks down in his seat, scrunches up his features and mutters, “Yuck!”

The ultimate impression Selleck gives is of a man either physically unable to let himself go or of a man hiding some terrible secret. In either case, he’s still so nice that it seems a waste of his energy to be so protective. He’s the kind of guy who would probably be even nicer if he just stopped acting that way and let himself be naturally so.

Selleck sits back now to enjoy the rest of the game. He looks around. It dawns on him that the fans’ attention is glued to the action on the field. “Hey, this is great!” he says. “Nobody asked me for an autograph. I’m escaping…. Oh, my God! Maybe they forgot me already! Maybe I should stand up or something. Turn around, let them see me.”

He laughs, only half-kidding.

[Photo Credit: AB]