“I’d rather hit than have sex,” Reggie Jackson offered up to the man from Time who was laboring on a cover story. “God, do I love to hit that little round sum-bitch out of the park and make ’em say, ‘Wow!’”

Sports Illustrated’s guy couldn’t get a hotel room; Reggie told the desk clerk he needed a room for his parents. “The interviewer points out all the reasons why it will be difficult for him to pose as Reggie’s mom and dad,” the interviewer wrote afterward. “He is one person, white, not named Jackson and only four years older than Reggie. ‘I could’ve been adopted, couldn’t I?’ Jackson replies.”

“If I played in New York,” he once confided to a bunch of newspaper guys, “they’d name a candy bar after me.”

Reggie Jackson signed with the New York Yankees last November 29; Standard Brands plans to have the Reggie bar—tentatively called Reggie Reggie Reggie—on the market before the year’s end.

Joyless souls will say that it has all worked like clockwork for Reggie Jackson, that, even for a man who does so many things so splendidly on a ball field—hits for power, drives in runs, steals bases, throws bullets—there is much method in becoming a celebrity. That—as one noted commentator has it—“he’s a .260 hitter with a .400 mouth.”

But the consensus is otherwise. To baseball fans all over the country, even to those who still regard the Yankees with the suspicion Frenchmen reserve for Germans, there is a certain poetry to Reggie Jackson’s coming to New York. He is, the sports writers have been telling us for nearly a decade, not only a slugger of epic proportions but a fun-loving, uninhibited, colossus of a man—Babe Ruth with kinky hair. Such a man had no more business in Oakland or Baltimore than the Empire State Building or the Metropolitan Opera. When Jackson at last became a free agent and twelve teams went after him, it seemed as immutable as any other law of nature; he had to choose New York.

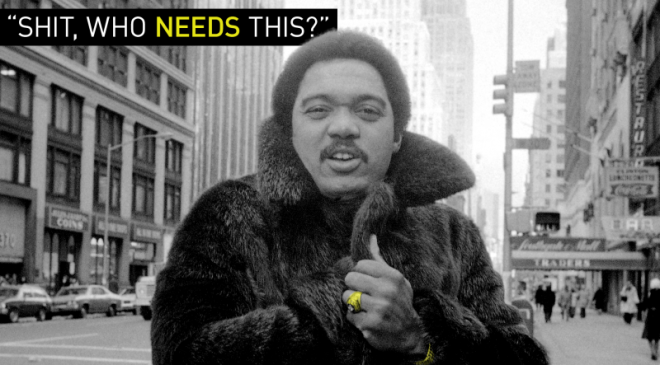

But it’s the damnedest thing; Reggie Jackson himself gets infuriated at the very suggestion. “I’m tired of hearing people say Reggie Jackson needs New York, needs the media, needs the attention,” he says, his dark eyes growing even darker. “I’ve always gotten it whenever I wanted it. I work for ABC television, I have my own syndicated TV series, I’ve been on the cover of Time magazine and on the cover of Sports Illustrated five times.” When Reggie gets very angry—and, incredibly, this subject seems to do it to him—he takes on the menacing air of a street fighter. He glowers at his questioner and his soft, precise voice—an announcer’s voice—wanders uptown. “So don’t give me none of that shit,” he continues. “I don’ need the money and I don’t need New York. I’m glad to be playin’ there—you understand?—but as far as my ego goes, you know, I mean, I can sit in my living room and dig my ego.”

Reggie Jackson is as mercurial as anyone you are likely to meet. In dizzying succession he can be disarming, reflective, earnest and—suddenly, inexplicably—hyper-defensive. The charm comes easily, seemingly at will, but always, just behind it, held back by a hair trigger, looms the anger. Over the years many people have had many things to say about Jackson in print, but none of those things is so apt as ex-teammate Bill North’s remark that Jackson “is an enigma and a paradox.”

Others put it less delicately. “He’s got a Jekyll-and-Hyde personality,” notes a behind-the-scenes colleague on Greatest Sports Legends, the syndicated television show Jackson hosts. “One minute he’s the most likable guy in the world; then, for no reason, he’ll turn nasty.”

“You’re not kidding,” agrees an associate, standing nearby. “A few weeks ago he blew up at me. You know why? ’Cause he tossed a golf club near me and I flinched. ‘What’s wrong with you?’ he screamed. ‘Don’t you trust me?’ I mean, he threw a real tantrum.”

The other shakes his head. “Yeah, he’s a strange guy, all right.”

Across the room—an office above Smokin’ Joe Frazier’s Gym in North Philadelphia—Reggie Jackson gives no indication whatever of strangeness. It is mid January, three months into production of the Sports Legends program, and he is now entirely at ease around cameras. He stands in a corner chatting amiably with the gym’s proprietor, boxer Joe Frazier, the subject of this week’s show. Ten minutes later, when the film begins rolling, Jackson is not only not strange but downright charming. Frazier is an awkward, rough-spoken man, a man slow in getting to a point, but Reggie, sitting beside him on a soft couch, handles him with a nonchalance and easy humor that soon has him completely relaxed and even, in an awkward kind of way, eloquent. Fifteen minutes into the filming, Reggie pops the payoff question, the one about all the years Frazier was characterized as an Uncle Tom by his arch-rival, Muhammad Ali. “The things that he said about me, you know,” answers Frazier slowly, “they only prove that I worried him to death….I know that within, this guy was scared, worried about things. He wasn’t sure whether he can take on the little fella….He had a lot of animosity in his heart. But it didn’t bother me, because I know what I was put together with, I know what I was ready for, I know what I was standing for.”

“I’m a businessman. I bring my bat and glove and attaché case to the office and go to work. I don’t give a damn if the other workers at the office like me or not.”

“Isn’t Reggie fantastic?” exults the producer during a five-minute break. “He’s much better than the guy we used to have, Paul Hornung.”

Back on the interview couch, Jackson and Frazier quietly compare jewelry—Reggie hands over his World Series ring and tries on Joe’s monster diamond—and they discuss their Rolls-Royces. The harried director cuts them short with a call for another take, then discovers his sound man is missing. “Warren,” he calls out irritably. “Warren, where the hell are you?”

“Hey,” says Reggie soothingly, “he might be in the bathroom, man. The man might be making a deposit.” Frazier and the crew laugh. Reggie Jackson, it turns out, was born into glibness. Reggie’s father, Martinez Jackson, enters the office moments later. Martinez has a bad leg, the result of a war injury in North Africa, and he moves with enormous difficulty. “Sorry I’m late,” he says. “I was working out down in the gym.”

Reggie springs from the couch, locates a soft armchair and places it at the foot of the couch, just beyond camera range. “Here, Dub,” he says. “You sit here.” He claps a hand on Frazier’s elbow and turns him toward his father. “Hey, Joe, you gotta meet my dad.”

This is the way Reggie is when Martinez is around. Those who spend a lot of time with Reggie say that even at his most withdrawn, Reggie changes in his father’s presence, becomes jovial, fairly gushes solicitude. To see them together for even a little while, it is impossible to miss the affection, and the esteem, they feel for one another.

There is, naturally, a story behind this. Reggie’s parents separated when he was three, and his mother took three of the six children from the Philadelphia suburb of Wyncote to Baltimore with her; he saw little of her for the next fifteen years. Martinez, a pugnacious little man whose feline features and pencil-thin moustache give him a curious resemblance to S.I. Hayakawa, ran a dry-cleaning business—and did some hustling on the side—to earn enough money to bring up his children in a white, middle-class neighborhood. The father was able to spend little time with the children—Reggie was generally under the supervision of an older brother—but his admiration for Martinez borders on awe. In interviews today he refuses to discuss his mother at all, but he will go on endlessly about his father; about the values—tenacity, faith, self-respect—he instilled in him; about how fine a ballplayer he was in the Negro leagues and how great a major leaguer he might have been; about how, even with his gimp leg, he would occasionally climb into a boxing ring and whip hell out of people; about how he taught him, by example, never to make superficial judgments about people. Later, in the big leagues, Reggie would be knocked by black teammates for consorting with whites. “Those guys,” he says now, “have a ghetto mentality. They just never learned how to relate to white people.”

But there’s an ugly side to the story, too. Not all of Martinez’ side businesses were legal in the narrow sense of the word—“He occasionally ran a red light” is how his son puts it—and when Reggie was a junior in high school, his father was taken away for a while. Reggie won’t talk about that either, except to say that his father got a shitty deal and that the episode turned him mean. This ushered into Reggie’s life a period of street fighting and beating up on weaker, richer kids.

All of that was long ago, of course, and Reggie says the scars have healed. But catch him in the midst of one of his brooding reveries, when he becomes, in the words of an ABC colleague, “a human glacier,” and it’s hard to be certain.

The crew moves downstairs to get some footage of Frazier in his gym. Reggie, clearly a novice at this sort of thing, flails away at a heavy bag in the corner. “That’s okay,” laughs Martinez, watching from his perch on the gym steps, “if no one’s hitting back at you.” He pauses. “Uh uh, Reggie wasn’t raised to be a fighter. No way.”

In spite of his own career in boxing rings throughout Pennsylvania and New Jersey, Martinez has a decided distaste for the mindless brawn associated with the profession. “Look at that,” he says a couple of minutes later, nodding in the direction of Frazier and the boxer’s sixteen-year-old son, Marvis, already a heavyweight with one knockout behind him; they stand three feet apart, exchanging blows in the midsection with a medicine ball, grunting with every thud. “Look at the difference between a fighter and”—he indicates Reggie, standing nearby, watching the scene intently—“and an athlete with a college education.”

Again and again, Martinez wanders back to the subject of college. He has one son who’s a doctor, he points out, and another who’s a lawyer. “And Reggie,” he adds, “he’s got a degree in architecture, just in case he needs it.”

This is not entirely accurate. Reggie, as he readily acknowledges, did not graduate from college—left Arizona State after two years to play professional baseball—and, in any case, was a physical-education major with a biology minor. But, for all his past troubles, Martinez Jackson remains a kind of romantic, a committed optimist, a man who routinely calls things as he’d like to see them.

His son inherited that innocence. Reggie’s ex-wife reports that before they were married, he was as firm in the conviction as she that they not sleep together. And, as a young ballplayer, he played the role of budding star with a joyous exuberance generally reserved for Little Leaguers and films starring Tatum O’Neal.

But, Reggie will tell you now, his illusions are long gone. After nearly a decade of celebrity—of baseball heroics, of blasts from other ballplayers, of vicious money hassles with the flamboyant and petty owner of the A’s, Charley Finley—Reggie Jackson pronounces himself forever cured of little-boyism. “I’m a businessman,” he says. “I bring my bat and glove and attaché case to the office and go to work. I don’t give a damn if the other workers at the office like me or not.” Martinez Jackson, who played second base for the Newark Eagles for seven dollars a game, frets over the game’s future. “This free-agent business,” he says gravely, “is gonna ruin baseball.” His son, who reportedly fetched $2,900,000 on the open market, totes up the number of tickets he will sell, computes the average price per ticket and explains how he is going to make a profit for his boss.

Martinez studies Reggie, standing on the other side of the gym, talking to his director. “People don’t know what it’s like to be Reggie Jackson,” he says. “For ten years it’s been the same—everybody grabby, grabby. It gets to a person.” He shakes his head. “Frankly, I don’t know how he takes it.”

Two hours after Jackson wraps up the Frazier show he is at the counter of a coffee shop at Philadelphia’s International Airport, awaiting a flight to Florida, where he will serve as a commentator on ABC’s Superstars show. Reggie is not happy; he misses his girl friend, with whom he has been quarreling, and he has a bad sore throat, which the Vicks cough drops he has been popping for the last half hour have done nothing to ease. He clears his throat and takes a quick sip from the cup of tea and honey sitting before him. “Shit,” he says, “who needs this? I should be home in Oakland.”

He glances morosely about him. Two guys sitting around the bend in the counter are talking softly and sneaking looks at him. Reggie notices them. “Man, the whole world wants a piece of you.” He takes another sip of tea, wincing as he swallows. “You know what I do? I’ve learned the knack of physically being in people’s presence—of smiling and shaking hands and letting people see Reggie Jackson the ballplayer in the flesh—while staying at home in my head. That’s the only way I make it.”

He falls silent. Around him, the curiosity is building; the waitresses have discovered who he is now, and a couple at a corner booth and the cashier.

“The thing is,” he continues, “I’m out there. I’m exposed. I’ve had my closest friends try to rip me off.” He shrugs. “But I’ve learned that’s just the world. I deal with it. I slide off, back away, cut ’em loose.” He smiles mirthlessly. “I could go bankrupt from my friends.”

How, the thought occurs, did this man get so pervasive a reputation for high-spiritedness, for flamboyance, for….

“That’s the media,” Reggie cuts in. “They don’t care if people know me, know my essence. They wanna sell newspapers. That’s the way the world works, man. That’s real.” He gulps down the last of his tea. “Every time something bad happens, nine thousand good things happen, but you only read the bad stuff. You don’t read how wonderful a guy is, you read what a prick he is. They sell newspapers with that crap.”

It has happened again. Over the last thirty seconds, Reggie Jackson has gotten angry. He leans forward and, speaking quickly, intensely, addresses himself to all the journalists he feels have done Reggie Jackson wrong. “Get a big story, you get credit from your editor, you move up the ladder, you get a nice coat, you drive a nice car. That sells. That’s our country. That’s the world. Knock me and it sells. Fine. Right on. Do your own thing, man, if that’s what makes you feel good.”

He pauses and glances around him. Just about everyone in the place is aware of him now. When he continues, the voice is still under control, but the eyes have become lasers. “I know that some of the press is out to get me. It’s ’cause I’m more intelligent than they are, I handle myself well, I’m wealthy and I’m black—and there ain’t nothin’ they can do about it.” He flashes his joyless smile. “There’s one columnist in San Francisco—a guy who don’ even write sports—who gets his kicks out of knockin’ me. He knocks me ’cause I got a Rolls-Royce. Well, if he’d get off his ass, he might be able to get one too.”

Reggie slumps forward on the counter, spent. “I’m startin’ to feel really bad,” he says softly. “I gotta shake this cold.”

In fact, Reggie has had a generally favorable press. What bugs him almost as much as the occasional slight is the fact that he is usually sketched in one dimension, as the superficial—albeit colorful—jock. Very few Reggie Jackson pieces mention the home for orphans in Arizona that he supports to the tune of thirty-five thousand dollars a year; or the fact that he once tried to organize an A.B.A. basketball franchise that would have starred Bill Walton and granted admittance to underprivileged children gratis; or that during his free-agent negotiations he suggested—and briefly tried to make a condition of his signing—that a retirement home be established for veterans of the Negro leagues. Part of the responsibility certainly belongs to Reggie, who does not readily discuss those things. When he talks about his future, for example, he generally mentions the security provided by his land-development business in Arizona and his ABC contract and his Standard Brands and Puma and Rawlings deals. But when he’s tired or down, he can wax every bit as mushy as William Bendix in The Babe Ruth Story. “I’ve been given opportunities and I owe it to my race and to God to give something back,” he says now, in the coffee shop of the Philadelphia airport. “You build a great boat and you can bring a lot of people aboard. If your boat is raggedy or half-assed, it’s gonna go straight down and then….”

And then, suddenly, the storm hits. “Reggie,” interrupts the cashier, hovering over him, “could I trouble you for your autograph? ‘To Maureen,’ if you would.” He signs, on a napkin. Two children from a nearby table follow her, then a guy from another table, for his girl friend, and an old guy, for his grandson. Finally one of the two guys from around the bend who’ve been watching Reggie for nearly an hour slides a pen toward him. “Two,” he says with a smile. “I have two sons.”

“You can’t be but so good an analyst, unless you been there, gotten knocked down, got your ass beat, got punched in the face.”

When Reggie is feeling good, when he likes someone, he will include the sentiment “Happiness is a way of living” above his signature, because, as he puts it, “maybe it’ll set someone to thinking.” This evening, however, the message on each of the napkins is a simple “Best Wishes.” He sends off the last of them and collects his thoughts.

“The thing I really want,” he resumes after a moment, “is a family. I was married once but I was too young and it didn’t work. But I still want to share what I have with someone. Someday, I’d like to wake up…”

“Reggie.…”

He looks up at a pair of waitresses facing him across the Formica, both of them white-haired and grandmotherly.

“…my friend and I would like your autograph, too.”

“Sure.” Reggie takes up another napkin and starts writing.

“He sure is big,” stage-whispers one waitress to the other. “Looks more like a football player than a baseball player.”

“He sure does,” agrees the friend.

“You’re a big boy, aren’t you?” This to Reggie.

He slowly raises his head and gives her his stare. “Pardon?”

“I say, you’re a big boy.”

A long pause. “Yes, Ma’am.”

“My grandson, he goes for football. He’s big.”

Reggie does not respond, just looks at her. After a couple of moments, the waitresses turn and retreat toward the kitchen. But Reggie’s mood has changed, and he has nothing more to say this evening at the coffee-shop counter.

Under the best of circumstances, Rotonda, Florida, the housing development that doubles as “Home of the Superstars,” is a dispiriting place to pass a few days, and the ABC people who trek there repeatedly gripe about it endlessly. But the circumstances on Reggie’s arrival this Wednesday night are downright ludicrous; the place is in the midst of the severest cold wave of the century—it snowed in Miami yesterday—and there is no letup in sight.

By the time Reggie makes it to his quarters, it is two a.m. In five minutes he is undressed and on the phone, trying to reach his girl friend in California. No luck; she isn’t home and in any case, her mother tells him, she still doesn’t want to speak to him. He hangs up the phone and is suddenly beset by a fierce coughing fit.

“The problem is my life-style,” he explains when it passes. “She’s tired of all the attention all the time.” He coughs again, but only once. “Shit,” he says plaintively, “where else is she gonna find a guy with ten million dollars in his pocket?”

He stands there in the middle of the living room in his underpants, thinking that over. “Ah, the hell with it,” he decides, heading toward the bathroom. “I gotta take a Rotonda.”

Reggie does not arise the following day for breakfast, nor for lunch, nor for the ritual presentation of The Superstars participants to the press. He does not stagger out of bed, in fact, until dinnertime, and then only for the most pragmatic of reasons: it is six weeks before the start of spring training and Reggie wants to stay strong.

Lousy as he is feeling, Reggie noticeably brightens as he approaches the Rotonda restaurant. The place is packed with athletes this evening, and Reggie has a special feeling about athletes. The experience of performing before roaring hordes, he feels, affects a man in ways which no one on the outside can wholly grasp. Though he professes admiration for several of his ABC broadcasting colleagues, he insists that they are, by definition, limited. “You can’t be but so good an analyst,” he says, “unless you been there, gotten knocked down, got your ass beat, got punched in the face.” He maintains too that professional sports emotionally equips athletes to triumph in realms far removed from playing fields. “The superathletes—the Pete Roses, the Jim Palmers—would make great leaders, great politicians. They have learned better than anyone how to handle pressure on a day-to-day basis. They live in a glass house.”

The customers at the Rotonda restaurant this evening may not be quite White House material but, taken as a unit, they’d probably make a hell of a congressional committee. The Superstars presents athletes from different sports competing in neutral sports—weight lifting, rowing, tennis, baseball hitting, track events, swimming—the idea being to determine the best all-around performers, and it regularly attracts top talent. This week’s show is heavy on football players, with a couple of jockeys thrown in for the sake of diversity and show biz.

It takes Reggie a quarter of an hour to make his way from the restaurant entrance to his table. He exchanges extended congratulations with the Oakland Raiders’ Fred Biletnikoff, lately the most valuable player in the Super Bowl; Bobby Bryant of the runner-up Vikings calls him over to his table and pumps his hand; fellow announcer Bruce Jenner, the Olympic decathlon champion, exchanges notes on the next day’s schedule; Cincinnati Bengals’ quarterback Ken Anderson, who looks like Beaver Cleaver come of age, offers some observations on the competition’s events; Angel Cordero, one of the jockeys, eyes the competition and holds out a little hand for his inspection. “Reggeee,” he says with a grin, “look, I got a scratch on my finger. You bat for me in the baseball heeting?”

But Reggie doesn’t speak to the man he’s most curious about, Heisman Trophy winner Tony Dorsett, the sensation of the college-football year, a sturdy, attractive young man seated at a table near the entrance.

“I hear,” says Reggie to Don Ohlmeyer, the show’s producer, who sits beside him at his own table, “that Dorsett is cocky.”

This is a serious allegation in the athletes’ universe. One of the favorite stories around the Superstars concerns the time, a couple of years back, that O.J. Simpson humiliated Anthony Davis, that year’s young hotshot and O.J.’s principal rival in the hundred-yard dash, by so intimidating him beforehand that Davis didn’t even show for the race. It is one of the great sorrows of Reggie’s life that at Dorsett’s age, he himself was perceived as cocky.

“Well, if he is,” replies Ohlmeyer, “wait till he gets to the pros.”

“In the pros we don’t take that shit,” agrees Reggie. “Guys on your own team will move away from you on the bench. Guys on the other team will go for your head. Nobody likes that shit.”

Reggie picks at his shrimp cocktail. “What did he change his name for, anyway?” he adds. The reference is to Dorsett’s request that the accent be put on the second syllable of his name, lending it a French pronunciation.

Ohlmeyer shrugs.

“I would never change my name,” says Reggie. “I wouldn’t do it because it would embarrass my parents.” He pauses. “I’m gonna call him Dorsett.”

“Call him Turkey,” says one of the ABC guys at the table, laughing.

The following midday, Reggie appears barely able to stand, let alone generate any antagonism toward anyone. A solitary figure by the Rotonda pool—the next event on the Superstars agenda is swimming—he looks for all the world like Napoleon on the Russian steppes: arms folded before him, full-length leather coat slung over his shoulders, he stares miserably into middle distance. “I just looked at myself in the mirror,” he says. “I look peaked—like a white boy.”

Nor does he feel free to wander far from this spot. Every time he steps beyond a thin restraining rope, he is set upon by people—old, tanned men after him for autographs, women with Instamatics, guys his own age who have apparently made it the day’s goal to shake his hand—and he simply isn’t up to dealing with them. Earlier today, en route to the medical tent for a breather, he scrawled only a few perfunctory “Reggie Jacksons” before brushing quickly through the crowd, leaving a sudden and vivid hostility in his wake.

Now, by the pool, the spectators, all of them admitted free to serve as atmosphere, are making new demands. Because of the weather, the athletes are slow getting to the starting blocks, so the crowd starts stomping its feet and applauding rhythmically. An ABC sound man looks up from his equipment. “Give ’em their money back,” he snarls.

A couple of minutes later, Keith Jackson, the anchorman of the broadcast team, takes Dorsett aside for a brief on-camera chat. Reggie edges close to them and listens in; Dorsett says the obvious, that he hopes to play in the pros and do well. “Hey, Tony,” says Reggie softly when it is over, “how old are you?”

“I’m twenty-two.”

“Twenty-two.” Reggie shakes his head. “I can hardly even remember when I was twenty-two.”

Dorsett smiles uncomfortably. “Yeah, well, you’re still going strong.”

Reggie doesn’t reply, just looks at him with a curious half smile, then slowly rises and returns to where he’d stood before and folds his arms before him.

“Lady,” says Reggie, “if you don’t know Reggie Jackson, you don’t know sports.”

Finally the races begin, two heats and a final. Reggie watches them with mild interest and then, on instructions barked through the button in his ear, springs to life; he rushes to the edge of the pool to speak to Fred Biletnikoff, who has barely edged out jockey Jorge Valesquez to finish second. Reggie is a master at this kind of thing; even in his reduced state, he will handle seven of this competition’s ten events and get more than twice as much air time as Bruce Jenner, his colleague and ostensible equal.

“Hey,” he says to the exhausted Biletnikoff now, with a naughty smile, “I thought you were supposed to be in shape.”

Biletnikoff smiles back. “Well, I think since the end of the Super Bowl I’ve been training in too many bars, Reggie.”

They both break up and—this’ll make a great moment in the show—Reggie gives him a shove that sends him flying back into the water.

His assignment completed, Reggie returns to his spot, drapes his leather coat back over his shoulders, folds his arms and, somber as ever, stares straight ahead.

“You know,” he says later, halfway through a hamburger at the Rotonda restaurant, “I never understood what people want with autographs, anyway. What good are they?” He takes a bite of his burger, then answers his own question. “It’s like everyone wants a little piece of you.” He calls over the waitress and orders a tea. “Not that the press is any better, with those five-minute interviews they’re always doing. Reporters actually ask me, ‘Do you do anything during the winter?’ I mean, c’mon man, that’s insulting. I’ll answer the guy, but in my head I’m thinkin’, ‘Uh-uh, man, you can’t play in my game. Wrong stakes. Next batter.’”

A lot of people, it is suggested, are going to say he’s crying all the way to the bank.

His eyes darken and he stares hard at his questioner before responding. “There ain’t nothin’ to say to those people. They ain’t never gonna understand. Those people…”

“Yoo-hoo,” calls a shrill voice from a table across the aisle, “are you Billy ‘White Shoes’ Johnson of the Houston Oilers?”

Reggie looks over at a plump woman in a black sweater emblazoned with red stars and dollar-bill symbols. She is the mother of Jo Jo Starbuck, a competitor in The Women Superstars, to be shot in a couple of days. Mrs. Starbuck is studying the photos from the press kit. “Billy?” she repeats.

Jo Jo, a wispy blond sitting behind her, blushes. “No, Mother, it’s.…”

“I’m Reggie Jackson,” says Reggie evenly. “I know we all look alike.”

Mrs. Starbuck studies the press sheet. “Are you in the competition?”

“No, Mother,” whispers Jo Jo, “he’s an announcer.”

“Lady,” says Reggie, “if you don’t know Reggie Jackson, you don’t know sports.”

Mother and daughter, both red now, return to their salads.

“What I’m saying,” picks up Reggie, as if the last thirty seconds haven’t happened, “is that I’m anxious to get past baseball and the damn spotlight. Sure, I enjoy playing—it’s been an outlet for certain tensions—but I don’t need it. It causes too many damn problems.”

He leans forward on his elbows. “Being a star’s a fake world, man. Hell, I can’t even conduct a decent relationship with a woman.” He sits back in his chair. “My dream is simple—having peace with myself, not having to deal with the public, not having to be somebody else. When I get through with this part of my life, I’m gonna live in Oakland or Carmel and nobody’s gonna…”

He is cut short by a tap on his shoulder from a young woman at the table directly behind him. She identifies herself as a reporter for The Washington Star, in Rotonda for a story on The Superstars. “We were just saying,” she says, indicating the young guy sitting beside her, “how strange it is that athletes just move into broadcasting with no training.”

“I think it’s odd,” replies Reggie, “that reporters can spend twenty-four hours down here and start spouting off about things they know nothing about.”

The reporter has her pen and pad out now. “I don’t think I’m spouting off. I’m here to report—and I really do try to be objective.”

Reggie stares at her. “Even about a guy who may do his job well but is antagonistic off the job?”

She jots that down. “I try.”

Reggie makes a sudden grab for her pen. “Can’t you just talk to me, have a conversation with me, without writing it down?”

She wrests her hand free. “I want to make sure I quote you right, don’t I?”

“Reggie,” tries the guy, with an easy smile, “what do you think you’d like to be doing in twenty years—say when you’re forty-five or fifty?”

Reggie looks the guy in the eye and snaps, “Are you asking that because you want to know or because you want to see if I have intellectual depth?” He turns back to the reporter. “Have you talked to Tony Dorsett?”

“Yes.”

“Why don’t you ask him why he changed his name?”

And so it goes. The reporter persists for twenty minutes, inducing him to offer only a couple of usable observations on The Superstars, before Reggie cuts her off with an abrupt “I gotta go to work” and rises from the table.

The experience puts Reggie in a foul mood. “That was a pain in the ass,” he says irritably, striding in the direction of the baseball field where the next event, baseball hitting, is already in progress. “Her story’s gonna be a scorcher.”

Moments later, when he gets within a hundred yards of the diamond, the crowd picks him up. “Shit,” he mutters, as they close in from three sides. He puts his head down and barrels through the crush, repeating softly that, sorry, he’s late, sorry, he has no time. Most of the people turn away, some muttering darkly after him. But one blue-eyed seven-year-old, in green suspenders and an oversize Detroit Tigers cap, remains by his side all the way to the field. Finally there are just the two of them, and Reggie looks down at him.

“Hey,” he says, “why do you want my autograph? I’m not an athlete.”

The kid returns his stare. “I know, but you’re Reggie Jackson.”

Reggie’s face erupts in an enormous grin. “All right,” he exclaims. “This guy’s got promise!” He takes up the kid’s pen and pad. “Happiness,” he writes boldly, “is a way of living.”

[Illustration by Sam Woolley]