A fresh gale blows down the chute of Central Park and buffets the windows of Miles Davis’s hotel suite in midtown Manhattan. A romantic might hear songs in this wet wind, the ghosts of seven blocks south and forty years past, when Fifty-second was The Street and all the young geniuses, Miles and Dizzy and Monk and Bird, invented the American musical equivalent of Cubism. Miles Davis is not a romantic.

He lives alone here, a king strangely in exile—from his three ex-wives and four children; from friends and from strangers; from the past; from the world itself. At sixty-three, he continues to tour and make records (his latest album, Amandla, was recently released by Warner Bros.), but he moves through the world on his own terms, changing band members, record companies, lovers, styles of clothes. He is a man doomed to movement, a man relentlessly in his own present, without apologies, without snapshots.

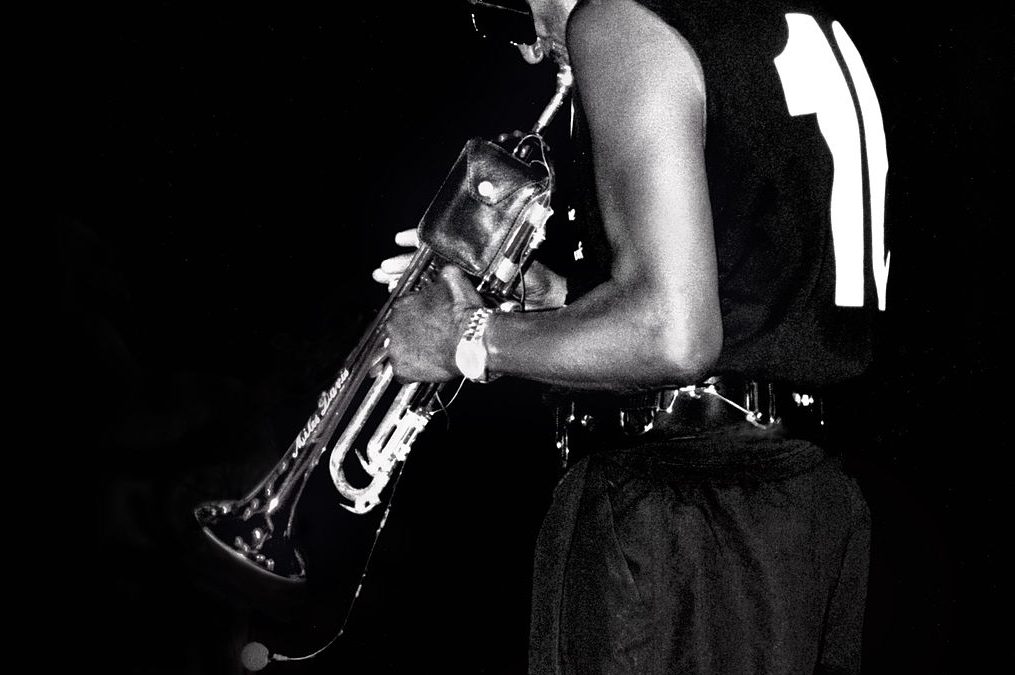

Fierce-eyed, farouche, Miles stalks the littered hotel suite, naked from the waist up, his torso slightly bloated but still a pugilist’s. He’s wearing black Vietcong trousers, one Ali Baba slipper (gold, with a curled and pointed toe), two thin gold necklaces, and a circular gold pendant. He limps (his legs were ruined when he wrecked his Lamborghini years ago; his left hip is plastic) amid scattered theatrical clothes, musical instruments, equipment trunks, mail (“IMPORTANT TAX INFORMATION’’), dirty plates and glasses, exercise paraphernalia. He shows a visitor his paintings, which he sells to the likes of Lionel Richie and Quincy Jones for five figures (the work is abstract and not at all bad; the two canvases over the bed resemble a cross between Hans Hofmann and Gustav Klimt). He picks up a Sony cordless, punches a number, and rasps the famous Miles whisper:

“Hello, Tony? Fuck you.” He hangs up. A syringe is stuck into the gray carpet, like a dart, next to the phone. (Davis, who says he has kicked several drug habits, is diabetic.) He lolls on his giant bed, toying, limp-wristedly, with his suspiciously luxuriant Louis XIV mane of curly brown locks. He shoots mists of water onto the hair with a plant sprayer. He plucks fruit from a plastic wrapped room service fruit plate; he searches the floor for something he’s lost. He finally settles down for talk.

In the background, the mindless choreography of a karate movie plays itself out, silently, on the big TV—but then, suddenly, after two guys exchange spinning kicks, there is the arresting sight of Forest Whitaker, who portrayed Charlie Parker in Clint Eastwood’s Bird, hulking onto the screen. A visitor, unthinking, asks Miles if he saw the movie. Miles looks as if a fly had landed on his food. “Naw, that wasn’t nothin’,” he says. “Now. What you want to know.”

He grew up in East St. Louis, Illinois, the middle child of an upper-middle-class family; his mother was a social worker, his father a dentist who raised horses as a hobby. The Davises were well-off, but there was no social insulation for blacks in the Midwest of the 1930s—the rich lived cheek by jowl with the poor.

‘‘Miles was always asking questions, and he always had a mind of his own,” his sister, Dorothy Wilburn, told me. ‘‘Once, when our father had a brand new Lincoln-Zephyr, Miles asked could he back it out of the garage. He was twelve years old, didn’t even know how to drive. My father said no. Miles did it anyway, and backed into a telephone pole.”

By that time, he had begun taking trumpet lessons, and soon music consumed him. Within two years, he was the best trumpeter in the state; he had his union card shortly thereafter. St. Louis was a jazz hub before World War II, and before long Miles was sitting in with the best musicians in the country: Lester Young, Dizzy Gillespie, Jimmie Lunceford, Charlie Parker.

The young artist was a dandy. ‘‘He always loved clothes,” Charlie Davidson, the founder of the arch-preppy Andover Shop in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and a friend of Miles’s in the fifties and early sixties, told me. (It’s a little startling to discover that Davis was a devoted patron of the shop in those years, when natural-shoulder sports jackets, button-down shirts, and narrow rep ties were, for jazz musicians, the equivalent of today’s Vietcong trousers.) Yet what he wears has always been as important to Miles as what he plays. “He once said that when he was in ninth grade, he told his mother he wouldn’t go to school unless she sewed velvet collars on all his jackets,” Davidson recalled. “At the same time, East St. Louis was a very tough place to grow up, and, dressed the way he was, he had to defend himself constantly. He didn’t mind.”

“When did you start boxing,” I ask Miles.

“We had a teacher—Ted Miles was his name. He used to come over to the house. So, you know, I never did have any trouble in school. Matter of fact, once when I was in Buffalo, I ran into a guy I boxed with when I was a kid. I said, ‘Man, what the fuck are you doin’ here?’ He said, ‘I was a professional boxer.’ I said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘After you kept beating my ass, I went to the gym and learned how.’ ”

By the time he was eighteen, Miles had to migrate to the Big Apple. His father wanted him to be a dentist; the compromise was that he would attend Juilliard. But Miles’s real purpose in heading to New York was to hook back up with the musicians he’d met in St. Louis, and this meant putting in extensive time on Fifty-second Street. Juilliard fell by the wayside. As Miles has told me, “One day I said, ‘What the fuck am I playin’ “Flight of the Bumblebee” for?’ ”

He continued to play it, really, only in a hipper way, teaming up with Charlie Parker to create what some white critics called “bebop” and what some black listeners called “the new music.” Mostly, the musicians didn’t call it anything—they just played it. It was fast, unpredictable, and you couldn’t dance to it. “There was definitely a damper put on this music,” tenor-saxophonist Wayne Shorter told me. “People called it cacophonous, discordant.” It made the big band arrangements of the thirties and early forties sound square. It was, as one album title had it, the Birth of the Cool.

“The only thing he’s really cared about over the years is music. He lives for music. He wakes up thinking about it. He goes to bed thinking about it. He says it’s a curse.”

“When I was fifteen or so, in Newark, New Jersey,” Shorter said, “I was one of maybe two or three people in my neighborhood who used to listen to a radio show that played this new music, with this new guy from Kansas City—Charlie Parker—and this strange trumpet player.”

“Bird used to attack the mouthpiece,” Miles says. “You know, the top of the mouthpiece—you could see it. You know, like, Weeuh weeuh whoah! Jesus! Bang! All the time. Even if he was sick, he’d play like that. Once he forgot his strap, and all that shit he was playin’, the horn fell right between his legs, and he had to finish it like that. ’Cause he was playin’ those things like Pres—doodee ooda doodee ooda—and you have to use freak fingerin’. And some of the fingerin’, don’t nothin’ hold the horn up but the strap. And he had no strap! So he had to use his legs. God damn.”

The slightly veiled sound of Miles’s trumpet, never giving too much, never explaining or ingratiating, was Cool itself. As was Miles himself. Right after nodes on his vocal cords were removed, Miles shouted in anger, against his doctor’s orders, turning his voice into a permanently whispery rasp. His pampered yet uneasy background and his childhood as a prodigy had made him naturally prickly and aloof, a prince. He was both effeminate (small and vain) and macho (quick with his fists). At the same time, he was preternaturally charming: prankish and funny. These opposites, the hardness and softness, made him devastatingly attractive to women.

“He was always fast with the ladies,” cabaret singer Abbey Lincoln told me. “I would call him a maverick. A mischievous, magical maverick.” She hasn’t seen Miles in years, yet there was a thrill in her voice. I asked if they had ever been lovers. “Well, I was his best friend’s girlfriend!” she said.

“Now, you roomed with Bird for a while in New York, didn’t you?” I ask Miles.

“He roomed with me.”

“Where was that?”

‘‘One Hundred and Forty-seventh Street. He just came by, you know. I got a room there—it was twelve dollars a week. Had a kitchenette. But Bird used to stop by my house and eat up all the fuckin’ food. He was just greedy, man. He would go days without eatin’, and when he ate, he ate a lot. There was this dollar meal. A cabbage stew, potatoes, little fatback, and a little piece of com bread like this. For me and my girl. That motherfucker cut half of the bread and took half of the rest. When he walked downstairs, I said to my girl, ‘Fuck Bird. If he stops in again, I’m not gonna invite him to dinner.’

“But Bird—I never did talk to Bird. I just worked with him. Once we were goin’ somewhere in a cab. And this girl’s with us. So Bird starts suckin’ the girl’s pussy, right? And he says to me, ‘J.R., turn your head!’ Bird was out, man. He had his own world.”

Like Bird, Miles had a heroin habit; unlike Bird, he survived. He was addicted to the drug for three or four years in the early fifties; then one day he decided to stop.

“I went out to my father’s and shut the door, and that was it. Just—smelled like chicken soup. . . Started to jump out the window, but it was too far down. Said, ‘I’d knock myself out, but I might break a leg.’ And I could hear his footsteps. . .we had a Colonial house on like about 265 acres, in Millstadt, Illinois. It’s like a master bedroom over here after you come upstairs, and the same thing on this side. So I just shut the door. And the maid would ask me, [high, querulous voice] ‘Junior, you want breakfast?’ I said, ’Fuck you! Breakfast!’ ”

After Bird’s death in 1955, Miles grew and solidified. It was as if he finally had permission to be a man, rather than a wild boy. He stopped playing in other people’s bands. By the late fifties, Miles defined Cool. He was jazz (he detested, detests, the word). Nobody was more brilliant musically. There have been only two sounds in jazz trumpet in this century: one was Louis Armstrong and the other is Miles Davis. All the rest are tributaries. But Armstrong always was who he was, while Miles has perpetually sought expansion. Two of his main influences in the fifties were pianist Bill Evans and writer and arranger Gil Evans.

Like Picasso, Miles is incomparably brilliant, endlessly influential, compulsively prolific.

“Well, you know, I’ve always been interested in theory. And if you listen to Rachmaninoff and Ravel and those guys put long sequences of modulations, I mean, it’s somethin’ to listen to. And Bill Evans hipped me to that. He said, ‘Listen to that.’ Every day we would do that. He brought me Ravel’s ‘Concerto for the Left Hand.’ Gil would send me Ernest Bloch. In the forties he sent me John Cage. Stravinsky was a favorite of mine. There wasn’t any music then that I didn’t like. And there’s never any music I don’t like now.”

Part of Cool was remove. Miles had acquired his reputation for extreme aloofness in the fifties: the mystique was both cultivated by him and augmented by others. He wore shades onstage, and often didn’t face the audience when he played. But there was a reason for this, as there was for everything Miles did.

“You ever see a jazz band? Here’s the stage; this is the microphone. Drummer, piano player. The setup of a quintet. You know, Dizzy’s like my brother, you know? But I saw he and Freddie Hubbard and Woody Shaw playin’ in Europe, right? This is a microphone—one of ’em play; get through playin’; go like this [stands and smiles]. That’s some borin’ shit, Jim. It’s awful. You know, I’d rather be hung than sit up there and try to be nice to a group of people that I don’t know. It’s the setup! When you get through playin’, you gotta step back, like you waitin’ on a TV shot. And it makes you, like, humble to the audience. For what? You’re givin’ them something!’’

Still, the myth of Miles’s aloofness stands to this day. We need Cool. Quincy Troupe, the as-told-to writer of Miles’s autobiography, which will be published by Simon and Schuster next month, told me, “When I was growing up in St. Louis, we used to talk about running away to New York to be Miles Davis.” The sentiment was not uncommon. In my own predominantly white, Jewish, and upper-middle-class hometown, a boy I knew of had his name legally changed to Les Davis, in honor of his idol.

“[Trumpeter] Donald Byrd discovered me when there was a blizzard in Chicago and his regular piano player couldn’t make it,” Herbie Hancock said. “The guys in the band liked my playing, so I joined them and went to New York. I remember Donald and I shared an apartment in the Bronx, and one day Donald said to me, ‘All right, it’s time for you to meet Miles.’ I was scared, man. Miles was the master. Miles to me was like Duke Ellington was to an earlier generation.

“Tony Williams and I joined his band on the same day, in May 1963. We had all new music. Miles didn’t ever like to repeat anything he’d done before. He had a reputation for being taciturn, but when I joined his band, I loved to hear him talk. Miles was funny.”

“Miles was a lot of fun as a leader,” Wayne Shorter told me.

“With the combination of Miles, Tony Williams, Ron Carter, Herbie Hancock, and myself, we were the loosest band in existence. I mean, it was Loose City. There were no rehearsals. Or we would rehearse on the telephone.”

“One time,” Hancock said, “Miles told George Coleman, who was playing tenor sax for him, I pay you to practice on the bandstand, not in your fucking room.’ ”

“There were no directives,” Wayne Shorter said. “But there didn’t need to be. We were very exposed, being Miles’s band, so everyone was on their toes.

“There was this aura around the whole band. We kept up this aura. And an aura is real. Miles was very proud of the people in his band, as well as the musicianship. I remember in six years I missed just one concert, and it was because of plane trouble. I think it was ’69. The band was playing at the Newport Jazz Festival, and I was coming in from Norway. We were supposed to open for Blood, Sweat and Tears, and by the time I walked in, in my tux, Blood, Sweat and Tears was starting to play, and Miles was coming off the stand. He just put my salary in my hand and said, I know what you mean.’ ”

By the late sixties, Miles was growing bored with acoustic jazz. Meanwhile, rock was ascendant, and jazz musicians everywhere were out of work. Miles Davis has never been out of work. “Miles knows how to take care of himself,” Abbey Lincoln told me, sounding both affectionate and worldly-wise. “He’s been a star for many, many years, and he always will be.” Davis recorded his first album as a bandleader for Capitol in 1949, and has recorded steadily (with one five-year hiatus in the late seventies), and extremely successfully, ever since—for Prestige in the early to mid-fifties, and for Columbia for thirty years thereafter. In 1985, an artistic dispute with Columbia led him to quit the label and switch to Warner Bros., where he’s been since.

“Miles is always breaking new ground,” says Herbie Hancock

His stylistic restlessness, his mystique, and his genius for playing ballads have made his records sell to three generations—and have allowed him to indulge his tastes for fine houses, art, automobiles, and clothes. “Miles has always done well, and lived well,” said record producer and Warner vice president Tommy LiPuma. But some charge that Miles’s artistic evolution hasn’t always been highminded. Jazz critic Nat Hentoff told me, “I once actually heard Miles say, ‘All these white guys are making $30,000 a concert playing rock ’n’ roll; I’m gonna show ’em.’ ”

Miles let Hancock and Ron Carter go; they were planning to strike out on their own anyway. Tony Williams and Wayne Shorter left soon after. Bitches Brew, recorded in 1969, said good-bye to the fifties forever. The all-electric album, which fused elements of rock with jazz, included such musicians as guitarist John McLaughlin and keyboardists Chick Corea and Joe Zawinul. The music was brooding and full of menace, and the record was a huge hit. It was also a kind of razor, slicing away a lot of Miles’s old fans. “Bitches Brew was O.K., but I think everything since then has been pandering,” Hentoff said. Many people felt the same way. There were a number of electric albums in the early seventies, many of them undistinguished.

At the same time, Miles himself was foundering. In the early sixties, he had moved into a town house on West Seventy-seventh Street with his wife Frances Taylor and his children Cheryl, Gregory, and Miles IV (none of Miles’s four children—his son Erin was born in 1971— were conceived with any of his three wives). The town house was a unique building, a former Russian Orthodox church that Davis had extensively remodeled. It was also a dark place. Miles’s marriage to Frances and then to Betty Mabry fell apart there, dissolved in alcohol and adultery. In 1975, Miles stopped recording and performing in public. He had lost his feel for the trumpet, he said, and he was bored with the music industry. But there were other reasons, too.

“When I was on Seventy-seventh Street,” Miles says, “I was usin’ a lot of coke. It was my house. It was a duplex, designed for me, no corners in it, just all circles. I was smoking six packs of cigarettes a day, drinking like two cases of Heinekens. So I wind up with diabetes and a bad liver.”

“Was there anything good that coke did for you?”

“Only thing wrong with coke is that they’ll bust you for it. That’s it.”

“So basically you stopped using cocaine because you didn’t want to get arrested?”

“There’s a lot of reasons for that one. The anxiety in snortin’ cocaine—it’ll finally dawn on you that you’re doin’ something illegal, and it’ll fuck with you. You can’t enjoy it. And you’ll hide it to keep from being busted. And then you say, ‘I’m not going to hide it; they’re gonna find where I put it.’ You get paranoid. So you take it all. And you get fucked up. Plus, you can’t make love with it.”

In 1967, Miles and a friend had been walking in Riverside Park when they met actress Cicely Tyson. At first, Miles wanted to fix Tyson up with his friend. But it wasn’t the friend she was interested in. Soon she and Miles were lovers. They continued on and off for several years, and then came together again definitively in the late seventies. They were married in 1981. But there were conditions.

“When Cicely and I started living together, I just sold the place on Seventy-seventh Street. ‘Cause I didn’t want those same guys comin’ by to—‘Hey, Miles! Let’s go hang out!’

“I stopped snorting when I went to urinate one day and it was this color [he points to the blood-red inlay on a Moroccan jewelry box]. So I said, ‘Fuck this.’ Then, not only that, but the same night, I went to get a cigarette, fell on [my hand]—I was still dead, you know—and my hand stayed like this [cramped position] for a month. I was paralyzed. Couldn’t move it.

“Cicely said, ‘Go down to Dr. Shen’s.’ I said, ‘Who the fuck is Dr. Shen?’ She said, ‘Maybe he can help you.’ So Dr. Shen told Cicely, ‘He had a mild stroke.’ But it happened at the right time.

“It wasn’t the coke that fucked me up. It was the whiskey, wine, and beer. And cigarettes. So I stopped. All of it at once. And then I never thought about it again.”

Miles and Cicely moved into her apartment at Fifth Avenue and Seventy-ninth Street, a safe distance from his old habits. In 1981, he began to record again, and he was quickly back up to speed. His album You’re Under Arrest, with its almost sunny interpretations of Michael Jackson’s ballad “Human Nature’’ and Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time,” sold phenomenally well. He almost seemed happy.

Davis and Tyson split up for good earlier this year. The divorce was not amicable; the only thing that seems certain is that this time drugs were not involved. They didn’t need to be. It appears that Miles and Cicely’s marriage fell victim to the same process that has always moved Miles forward: Stasis is death. History is stasis. Marriage is history.

With Miles, history keeps getting in the way of his extreme distaste for remembrance. He has often said that the only way to make art is to forget what is unimportant. This might mean your name, or your very existence, if you came to see him two days in a row; it has also meant, at various times, his wives, mistresses, children, old friends, colleagues.

Like Picasso, Miles is incomparably brilliant, endlessly influential, compulsively prolific. Also like Picasso, he is, in many ways, a supremely isolated man. “He always seemed lonely,” Nat Hentoff told me, “even in a roomful of people.”

Nowadays Miles spends most of his time in the Essex House suite, occasionally visiting his seaside villa in Malibu, which he shares with his youngest son, Erin. Miles is trying to be as close as he can to him, to make up for time he couldn’t give to his other two sons, Gregory (now Rachman) and Miles IV, both of whom have had troubled lives (the former has spent time in jail), struggling with the tremendous weight of a monumental father. (Maybe it’s easier for a daughter: Cheryl, forty-five, seems to lead a normal life, as a schoolteacher in St. Louis. But she won’t speak for publication.) Miles doesn’t like to talk about his kids, and they don’t like to talk about him. The same is true of his former wives, and former and current girlfriends. I met one lady friend, a tall, cool, dark-haired artist, when I visited his Essex House rooms. She nodded at me and stayed mum. As did Miles when I asked about her.

One night I phoned him, wanting to clear up the extremely complex matter of his wives, his girlfriends, his children. He was alone in the suite, playing a guitar. “What you want to talk about that shit for?” he rasped, almost in agony. “My ex-wives? My ex-children?”

Old friends drift away in the wash of history. “Many people he’s known don’t call anymore,” Quincy Troupe told me. Troupe, Davis’s Boswell, knows Miles better than anyone knows him; he also remains mystified by him. “I saw Max Roach and Sonny Rollins the other day,” Troupe said. “They said, ‘How’s Miles?’ They used to all be like brothers! Miles still says, ‘Max is my brother.’ But they don’t see each other.

“The only thing he’s really cared about over the years is music. He lives for music. He wakes up thinking about it. He goes to bed thinking about it. He says it’s a curse.”

“Is either of your parents still alive?” I ask Miles.

“Nah, they’re dead.”

“When did they die?”

“I can’t remember. Think it was in the sixties.”

“Miles stays in the house,” Troupe said. “He gets his information from TV and newspapers. If he goes out, people recognize him; they bother him.”

Old men, T. S. Eliot once said, should be explorers. Miles has always been that, and now, as he approaches an age when many men seek their comfort, he continues to explore—fusion; funk; Zairian music, Antillean music, Nigerian music; ever more sophisticated rhythms and electronics. “Miles is always breaking new ground,” says Herbie Hancock (who’s broken some ground himself, and ruffled some feathers).

“It’s in his blood.” Old fans, stuck on memories of making love to Kind of Blue, howl in protest. “I think his devotion to electric music, and the wild costumes he wears onstage, is all very carefully thought out, and I think it’s absurd,” Charlie Davidson, of the Andover Shop, told me. “Now his idol is Prince!”

“I was gettin’ ready to get in a limousine, in Los Angeles,’’ Miles says. “Prince walked up behind me and said, ‘Hello, Mr. Davis.’ I spent some time with him at New Year’s Eve last year. He talks to me; I call him up. You know, I told him, he gets so thin that I worry about him. I said, ‘Just call me.’ ”

“What do you listen to these days?” I ask Miles.

“I like the rap music, you know, because it has no direction—it’s just raw. I have a girlfriend that’s German, and her son goes to sleep to Run-D.M.C.! He won’t go to sleep without she puts the cassette on. They asked me to play with ’em, you know. Run-D.M.C. ‘Cause I was always fuckin’ with ’em in the Grammy Awards. Said, ‘Man, what you doin’ here? You ain’t gonna win anything.’ ”

Miles Davis and I are alone in his hotel suite, listening to his new album. The sound is electric, polyrhythmic, soulful, Afro-Caribbean. The trumpet is supple and laconic, as virtuosic as ever, as coolly passionate. I’m reminded of what Herbie Hancock told me: “I think he sounds beautiful these days. When he first got the electric groups together, I thought, This is the fruit of what he was looking for when he played with us.”

But somehow this driving Afro-funk makes me recall how beautifully Miles has always played ballads—the longing expressed all the more strongly by the restraint. And I can’t help myself. It just pops out: “Will you play standards anymore?” I ask him. “Would you ever play ‘Body and Soul’?”

I regret the question as soon as I ask it; I’ve seen how easily his friendliness turns to scorn. But for a second he looks almost sad. “I was hummin’ that last night,” he says, and the idea of Miles, alone in his suite, humming “Body and Soul,” is nearly overwhelming. Then the scorn comes. “These kids don’t know anything about ‘Body and Soul,’ ” he rasps.

The wind rattles the heavy panes of the Essex House. Miles Davis is walking into time.

[Photo Credit: Den Haag]