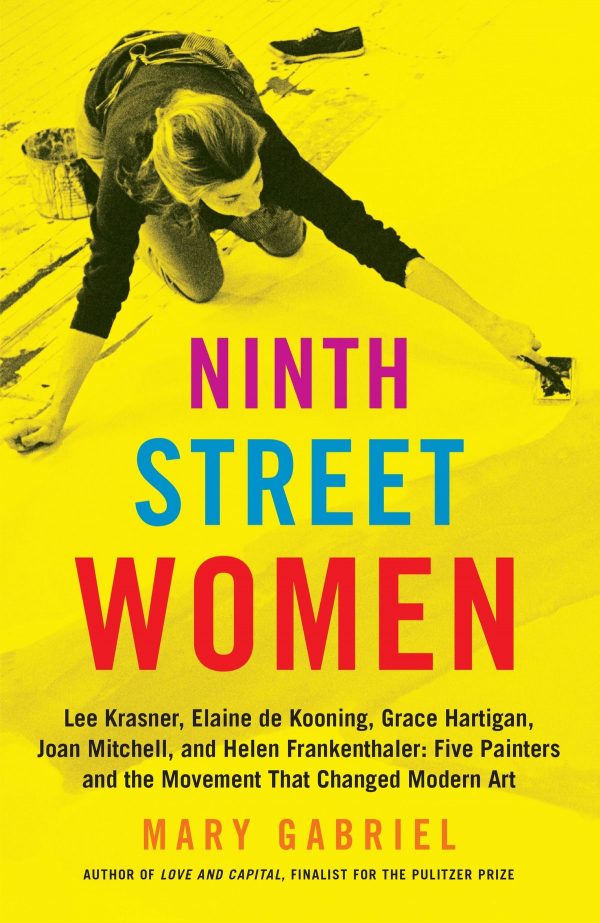

If Mary Gabriel’s irresistible book about the mid-century New York art scene, Ninth Street Women, feels a little like a Robert Altman movie—with favorite characters weaving in and out of the story—it’s because she has a natural affinity for the ensemble.

“I only make soups or stews,” says Gabriel. “I don’t make little delicate dishes.” And what a tasty stew her tale of New York from 1929-’59 turns out to be—meticulously researched, written in a lean, conversational prose, this massive book is light on its feet. It breezes along and Gabriel writes about art without being obfuscating or pretentious.

My uncle Fred went to Cooper Union in the mid-’50s after he got out of the service and he frequented the Cedar bar nipping at the heels of his idols like Kranz Kline and Willem de Kooning. His sensibility as a painter was formed during those heady times and he passed down his reverence for those guys to me. Fred died a few years ago and so I read Gabriel’s book with special urgency and delight because it evokes the world Fred told me so much about.

Recently, the paperback of Ninth Street Women hit the bookshelves, all the excuse we needed to get in touch with Gabriel and chat about when New York became the art capital of the world. Dig in.—AB.

Alex Belth: Your book isn’t just about five painters, it is about an entire art scene over a 30-year period in New York City. How did you decide on the focus for the book?

Mary Gabriel: Biographers are a little bit like time travelers. You go back and absorb lives. I got to absorb five lives, and all those peripheral people, and you know, what an incredibly dramatic time. And to live that creative life with them. I was a couple years late in turning the book in and about 400 pages over my limit, but I had a really wonderful editor, and she kind of let me go.

AB: You did yourself a service by confining it to 30 years, but did you find that once your editor let you go, she was actually pulling that back and tightening a lot of that stuff?

MG: If you’re gonna do five people, I’d have to write an encyclopedia, it would have to be five books basically. So it’s not just a book about those five people, it’s also a biography of a movement, and also a social history. So, 1929-1959 that was really the lifespan of that movement, and it fit neatly because Lee Krasner, who was the eldest, came onto the scene at about that time, and as of 1960 the art-buying public had discovered Pop, so the headstone had been placed on the grave of Abstract Expressionism.

AB: The first four painters were known to me, but I didn’t know from Grace Hartigan. I loved the way that she was your unwitting door into this.

MG: I was an art student myself. I wanted to be a painter, but I didn’t see any path. It’s hard enough as a guy to be a painter and make a living, but to be a woman there was no path that I could see. I was at the Maryland Institute College of Art and the head of the graduate painting department was Grace Hartigan. But I was so inculcated with the western art tradition, that because she was a woman, I didn’t really pay any attention to her. I mean, can you imagine that? And here I was aspiring to be a painter and yet I was already condemning myself to second class citizenship and failure.

When I became a journalist, one of my first jobs was at an art magazine, and Grace was having a resurgence of activity. She had a bunch of shows and a monograph, so my editor said, “Go see her.” And I have to tell you, I was scared because I knew she was a tough cookie. I mean really tough. She was physically formidable and was not at all, I thought, a generous or sympathetic person.

Interior, ‘The Creeks,’ Grace Hartigan, 1957.

So I stood outside of her studio, which is in this really grungy part of Baltimore, you know, real sailor’s kind of neighborhood, and I was just scared. She opened the door and she was absolutely charming. And whether this was an act—she was a great actress—or I had just completely misread her. So anyway, we talked for a long time and she told me this incredible story about her life in New York and the women and men she worked with and loved, and the wild times, and how this wasn’t a theoretical exercise on their part. They weren’t discussing the marks they were putting on canvas as a theoretical exercise. They were in it body and soul during a time when the world was falling apart: the Depression, World War II, the McCarthy Era, the Atomic Bomb. They were responding to their world.

I can tell you, as an art student, I took more art history courses than studio courses, which was probably an indication to me that I was in the wrong place—I should’ve been with words. But, in all of those art history courses, I had never heard this lesson. I had never understood that much about Abstract Expressionism. In fact, in my arrogance I’d kind of written it off. It wasn’t that interesting to me. But hearing her perspective and hearing her story told through her wonderful, colorful, great words, I left there thinking, “Wow, that was a really great book.” It was an amazing story and I wished that I had read that when I was a painter because I might’ve seen, okay there was a possibility.

That was in 1990. Then I had a lot of other things happen and I didn’t get around to writing it until 2011. But incredibly, can you imagine, in all of those years no one else had done it? So the story was just there. It just took some digging.

AB: It’s interesting you hear you say that as a woman your own perception was to devalue your own conception of what it was you could be. It seems as if while the women in your book definitely had to deal with the machismo and insecurity that existed within the men of that period, they also got on with it. They didn’t seem to be tripped up by it so much.

MG: Not at all. It’s almost retroactively that we impose that narrative on them. First of all, we ignored them, as contributors to that movement. But also the story became the story of macho men and they wouldn’t have recognized that story because they were in it. They were contributing artists, fully involved. I think without Lee and Elaine in particular, the movement wouldn’t have evolved as it did. They were central figures. I wanted to restore the story. The story has become narrower and narrower through the years, and it’s basically Rothko, de Kooning, Pollock, and there all these other characters—not just the women. If you withdraw one of those characters from the whole scene, the web falls apart because they were all part of it. It was this wonderful, throbbing fabric, and I hope that comes across in the book because it just seemed like such an incredibly rich and powerful moment. There wasn’t a first class and a second class group, including divisions between the men and the women, they were all there together.

AB: You don’t sanitize the past either. I forgot which Village café where they hung out in the ’40s but you just talk about that there was a menace in that place, the sailors and tough guys, and how rough it could be.

MG: It was very edgy, the Cafeteria on Sixth. It was scary because during the war a lot of the cops became soldiers, they were drafted or enlisted. So the streets were dangerous places, especially for women. But that was one of the things, these women dared to go out and be a part of it. There were a few incidents that I didn’t write about because they weren’t germane to the story. One where Elaine was attacked. There were some others that the women had pretty serious incidents, close calls, but those were the streets. It wasn’t fairy land, those weren’t the good old days. New York was tough then as it was tough in the ’70s.

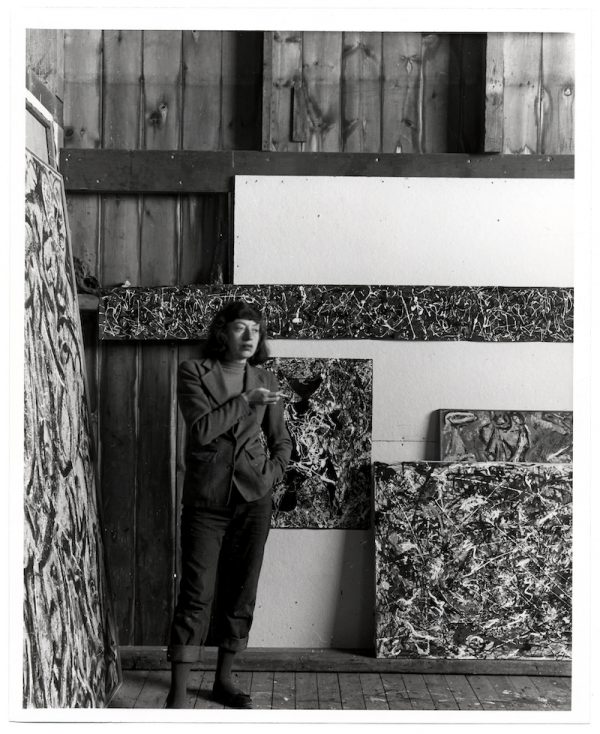

Lee Krasner in Jackson Pollock’s studio, 1949.

AB: It’s easy to look at Lee and Elaine and say, “Oh these are women who subjugated their own talent as painters to their husbands,” but there seems to be even more to it than that. That they were also incredible talent scouts, they understood what they were seeing.

MG: There was nothing about their lives, the way they lived them, in which they fell into that traditional wifely role. Lee possibly slightly more. She learned how to cook, which Elaine never bothered to do. But it wasn’t that they were promoting their husbands because that was the role of a woman and they weren’t abandoning their careers because that was what they should’ve done as of 1940s 1950s America. They were in love with art. Clem Greenberg said Lee had the best eye in the country for painting in the ’40s. Lee was always on the lookout for new art and what she saw in Pollock was something she had never seen before. She said the earth moved when she saw his paintings. Now, she happened to fall in love with the guy as well, but I really think that if she hadn’t had been in love with him, she would’ve pushed his paintings. She was almost like an art vigilante because the time she was organizing for the WPA and the federal art project, she was always a protectress, a lion defending artists.

That’s what she did with Pollock because he needed it. He was a mess, and also because his art was so tremendous. So it really isn’t fair when people portray her as being another little missus who put down her paintbrush—which she never really did—to defend Pollock because that was the role women had in those days. It wasn’t that at all. Lee was a fierce advocate of painting, and she saw in Pollock what she thought was the best painter she’d ever seen in her life.

Elaine was similar with Bill. She said there wasn’t a greater painter that she’d ever seen. She was absolutely expert propagandist, so she employed all of her skills—her beauty, her charm, her writing ability, her organizational skills. She was one of those people with a zillion tentacles and she used them to help everybody, to help that whole community, but also Bill. It’s funny how much I run into people who still resent Elaine. They’re jealous of her. It’s amazing. Some of the older women, not any of the ones I spoke to for the book, but many of the ones on the circuit disparage her, “Oh Elaine de Kooning, she used her body, she slept around.” Edith Schloss, who was married to Rudy Burckhardt, who knew Elaine exceedingly well, who was part of her circle in Chelsea, said, “No, on the contrary, part of Elaine’s allure was that she didn’t sleep around.”

Bill and Elaine de Kooning, 1944.

When she got older, when booze became part of the scene, she did, but everybody did. The gates were open and everybody acted crazy. But Elaine, Elaine was this social character who did everything she could to help everybody she could, everybody who needed it, and since all of her friends were in the art community, that’s what her focus was. And one of those people happened to be her husband and she worked really hard to promote him, but it wasn’t exclusively Bill she helped. The only person she didn’t help was herself.

AB: Mary, can you also talk about the sensibility that informed those painters, particularly in the ’40s before anyone became famous. The notion of being a careerist would be the furthest thing away from their mind. One imagine that sticks in my mind is when Elaine wakes up one morning to find that de Kooning destroyed this incredible painting he’d been working on because it wasn’t up to his standards.

MG: Today, we often talk about value in terms of monetary value: what’s a painting worth? That would’ve been the furthest thing from their minds. No one was buying their work. The most any of them could hope for was that one of their friends would buy it, maybe for $100. That would be huge. They could pay rent and just exist for the next couple months. It’s difficult for us to even understand where they were coming from because it almost seems an idealization of their life to say, “they were so pure.” But they were, and partly it’s because there was no tradition for what they were doing in the United States. There hadn’t been a modern art movement in the United States that broke the kind of ground they did, that challenged the history of western art, that was so new that nobody had ever seen before. They were working for each other in lower Manhattan or Long Island, feeding off each other intellectually and artistically and, if they could help, financially. So the values that drove them were purely creative and I think spiritual, to be honest with you.

The Depression was the only time they had money they could count on for their art, because the government was paying them. I mean can you imagine? Roosevelt was the greatest art patron probably in American history because he created an entire generation of artists through the WPA and also art appreciators because Americans were introduced to the notion that there were these people called artists whose work could be looked at and what they created was of such value that the government would extend them a paycheck.

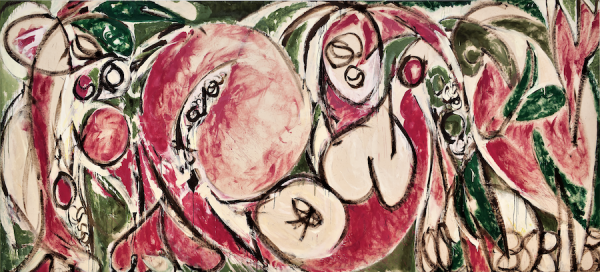

The Seasons, Lee Krasner, 1957.

But in the ’40s during the war when the issues that these people saw in the movies at the newsreels or on the newsstands on the front page or that they knew because their comrades had come back from the war, the kind of spiritual deprivation that they were experiencing during that time because they knew what was happening. People say Americans didn’t know about the Holocaust. People knew exactly what was going from fairly early on. It was all over the newspapers, but you could choose to read about it on page 12 or not choose to read about on page 12. What drives a lot of artists, or what should drive a lot of artists, is that their job is to give people a window into this deeper reality or a way to cope with things that they don’t know how to cope with or a greater understanding of life or love or hope or death. All those things that religion also does.

Artists fill that same function. So that’s what they were doing with their work. They couldn’t do it with any of the pictorial tools they inherited like landscape or the tradition of portraits or still lives, so they had to create something new. They had to start from scratch, and that searching within themselves for a new image that would explain the madness around them kind of gave a little bit of a window or hope that there might be something better or greater than what people had just lived through, which was the War and the Depression. I think that’s what drove them. The idea that making money off of that didn’t enter their minds.

AB: And at the peek of their eventual success, Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein showed up and were a perfect ‘60s smart-assy tonic to the Abstract painters, who wore their heart on their sleeves. It’s easy to make fun of a method actor too.

MG: Those pop artists you describe absolutely reflect their times. The ’60s was about Go, Go, Go. The Kennedy administration. The world had changed and the art reflected it. Abstract Expressionists spoke to another era, when the world didn’t make sense and there might not be a tomorrow. By the ’60s the world had kind of absorbed that shock: There may not be a tomorrow so let’s live it.

A: It felt like you had a great affection for a couple of recurring characters in this story. Every time I saw Hans Hofmann or Franz Kline or Frank O’Hara appear, I was like “Oh! They’re back!”

Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Jackson Pollock, and Willem de Kooning, 1950.

MG: I pretty much fall in love with all the characters, but there are a couple in this book that I really loved. Hofmann a little bit. Franz I really loved. but Larry Rivers and Barney Rosset, I just absolutely loved. He is one of the unheralded people from that period. For better or worse, he is the reason there are pornographic movies, that we can say or write anything we want. He inherited $50 million in 1952 or 1953 and spent it all by the early ’60s on censorship fights on behalf of all of us. He was another one who used all of his effort and all of his money for something bigger than himself. He didn’t give two shits about money. It was all big picture for him.

When I started this book, I couldn’t stand Jackson Pollock. I thought, I don’t know if I can write this book because I’m gonna have to spend a lot of time with him. But by the end of it, I loved him. Because I saw him through Lee’s eyes mainly. I learned to love him through Lee’s eyes. When he wasn’t painting, he must’ve been in agony most of the time, and he was only alive during those moments in his studio. By the end of the book, how can you not appreciate it? Some people say I wasn’t judgmental in this book, well, how can you be?

Paul Jenkins called him a window breaker. And that’s what he was for them and that’s what he was for us. You hear about the jazz musicians in the Five Spot and Ornette Coleman saying, “My music is like Jackson Pollock’s paintings.” He showed a way for not just painters but writers and musicians to do their thing better, in a different way.

One of the things, and not to go off the subject, but I think one of the things that happened when I was in art school, there were all these young boys—this was in the ’80s—they all thought they were Pollock, and thought they were really cool. But there were no cool women remotely who you’d want to be like. Georgia O’Keeffe, but she’s kind of a nut. What, Mary Cassatt? Artemisia Gentileschi? Where are you gonna go to find somebody you want to be like? Because you need to be able to see yourself in someone else in order to know it’s possible, unless you’re a real astronaut of a person and you can just focus and forget the world.

AB: But if you were a musician you could’ve thought of being Grace Slick or Janis Joplin or any number of people, there was at least someone that you could’ve looked at.

MG: That’s right. I interviewed one lady who was Elaine’s best friend. She was 100 years old when I interviewed her. She was so good-looking still, so completely with it, by the end of our interview, which was four hours, I was dizzy. I had another interview lined up and I could barely put two words together I was so tired. Earnestine was rearing to go. And she said that her main objection to the things that have been written about the scene in general and the women in particular was that nobody showed how much fun they had. What sustained them? It was their community. They weren’t talking to each other on the phone, they were in the bar together every night. And at first it wasn’t about drinking so much, it was just about being there and having a good time. And when you read some of their antics, it was fun, it was wild. This was 1950s America, but it was so out there, it would be still wild today.

AB: And especially because even in the big, in big bad New York, that community was small enough that you could probably find your way to those guys pretty fast.

MG: Exactly. Well, think about Grace Hartigan, she was from New Jersey, a housewife with a kid and a failed marriage. She arrived in New York, knowing she wanted to paint, not really knowing how to do it, never having had any proper training, and within one year, she was cooking dinner for Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner. That’s how small the community was. You could enter it immediately, you just had to go to the right bars.

AB: Yeah, that’s right, and the other character that’s a major figure here is New York. It’s not just how you’re describing how in history there’s a shift from the art capital of the world going from Paris and now it’s in the United States, in New York, but also you read a book like this, and you just again are astounded by, American culture was completely shaped by Hitler, because New York suddenly gets dumped on by all the psychoanalysts and the surrealists all the sudden they’re two blocks away, they’re here.

MG: I know, isn’t it amazing? And when you think about it, art historians, the psychoanalysts, the gallery owners, the painters and sculptors and writers, they’re all here. Some stayed in New York, some spread out around the United States. It was an influx of intellectual talent that was like a tsunami really. And those artists, that whole community in the Village, they were receptors. They absorbed it all. It’s not like they painted like the surrealists, obviously not, they just absorbed what it was to be an artist, what you looked like as an artist, how you lived as an artist. The second World War changed life on the globe, but in New York in this little group it changed it for the better because of the people and ideas that they were exposed to.

Helen Frankenthaler, 1954.

AB: Frank O’Hara was a revelation to me in your story. Did you know how much of a role he played in the art world before writing?

MG: I only knew from Grace that he was the love of her life basically, so I knew from her that he was important, but I didn’t understand how important he was for their work. When he was working as a curator for the Museum of Modern Art, he was introducing all his friends to the world through their shows. So Frank was kind of the poet who opened the painting scene up, with Elaine’s help, to poets and that’s how the Beats sort of arrived and how they started hanging around. But they were the young kids. They were the bad boys.

AB: And they were more of a boys club too weren’t they?

MG: They were a real boys club. Even Joan Mitchell, who considered herself part of any boys club, she considered them too much of one to hang around with. Barney Rosset, who was Joan’s first husband, with his Evergreen Press, was the first person to give free rein to the Beats and publish their work. Joan was living in Paris, and Ginsbgerg was there hiding out, and William Burroughs showed up, so a few of them were there. I think Gregory Corso was there also. So Joan was hanging around with them. But there was no cross fertilization from the Beats to the painters, it was more the painters to the Beats.

There was a generation of poets who absolutely was completely enmeshed with the Abstract Expressionists. They were influenced with the painters, the painters were influenced by them, and that was the New York School of poets: John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, Jimmy Schuyler, Frank O’Hara, and Barbara Guest. There is no line that divides the poets and the painters. They were together in that group. They were at the same bar together. They were at the club together. They were influencing each other.

The Beats came in after that so they weren’t really a part of it. The musicians, however, just talking about the jazz musicians, John Cage and Marty Feldman, were and Cunningham too as a dancer, can you imagine in the club on an evening you might’ve had all of those people and they were all feeding off each other, so how could a revolution not occur? There’s one description of John Cage who was on a trip with Merce Cunningham and it was hot and there was a roadhouse behind them and they heard from the roadhouse the jukebox and the kids’ laughter and the heard from the road the cars going by and they heard whatever sounds of nature might still be audible, and John Cage said, “This is music.” And when you think about those contributions to his sound, and then you think about an Abstract Expressionist painting, it’s the same thing. It’s the boom-boom-boom-boom of the paint. The other thing is, the lack of money gave them such freedom. There were no constraints. They could do whatever they wanted. Creativity was the goal. It was the prize.

AB: One thing I was aware reading your book is how you champion the women painters of the New York School without denigrating the achievements of the men. Did you catch any criticism for that?

MG: Yeah, I have been criticized for having too much about the men in the book. But whenever, my last book was about Karl Marx and his family, and I’d actually started writing that book just to be the story of his wife and his daughters. But I couldn’t write their story without talking about Karl Marx. I would be guilty of the same historical inaccuracies as people who’ve written about only the men have been if I’d written about only the women, and how do you understand the women unless you put them into context?

I just wouldn’t be interested in writing that book. I think there’s no diminution in the stature of the women by also talking about the men. In fact, I think it puts them in proper perspective and allows you to appreciate them more. And as I said before, I came into the book not really liking some of these men and I came out of it understanding them and their work and the whole scene better. And I’m so glad for that, and had I not paid any attention to them, I wouldn’t have had that experience as a writer. I only make soups or stews, I don’t make little delicate dishes.

City Landscape by Joan Mitchell, 1955.

AB: Sometimes books can try to shoehorn the events of the world into the narrative in a way that feels forced. But in this book I enjoyed how much time you spent writing about world and local events because it really puts you in that moment.

MG: Part of the reason I go off these historical paths that a normal art history book might not is because I’m a journalist. I’m not an art historian. I’m always interested in what’s happening around these people. Martha Graham, the dancer, said, “You can’t imagine the impact that the daily headlines had on the muscles of your body as a dancer.” You can only imagine as a painter or a sculptor how what you see or what you experience around you does to what you create on canvas or in your studio. So I was always conscious of that bigger picture.

There is a scene in Carnegie Hall when Pearl Harbor was first announced. I got that from a taped interview with someone who described being at Carnegie Hall when they first learned of Pearl Harbor. We all know what Pearl Harbor is but they didn’t know what Pearl Harbor was. Where the hell is this? And that kind of thing, just to say that the world has just changed, and it happened somewhere, and we’re not sure where it is but we know it’ll never be the same, I loved being able to do that.

[Featured Image: Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, Grace Hartigan (left to right) at Helen’s 1957 opening at Tibor de Nagy. Burt Glinn, photographer. Courtesy Magnum Photos.

Photo Credits: Lee Krasner in Jackson Pollock’s studio, 1949. Harry Bowden, photographer. Harry Bowden Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution; Willem de Kooning and Elaine de Kooning, 1944. Ibram Lassaw, photographer. Copyright Denise Lassaw, Ibram Lassaw Estate; Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Jackson Pollock, and Willem de Kooning (left to right) at the Museum of Modern Art, ca 1950. Photographer unknown. Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution; Helen Frankenthaler at her West End Avenue Apartment in front of Mountains and Sea. c 1954. Photographer unknown. Courtesy Helen Frankenthaler Foundation.

Paintings: Interior, ‘The Creeks,’ Grace Hartigan. Oil on canvas, 90 7/16 by 96 ¼ inches, 1957. The Baltimore Museum of Art, gift of Philip Johnson, New Canaan, Connecticut, BMA 1983.45. Photograph by Mitro Hood. Copyright Estate of Grace Hartigan; The Seasons, Lee Krasner. Oil and house paint on canvas, 92 ¾ by 203 7/8 inches, 1957. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from Frances and Sydney Lewis by exchange, the Mrs. Percy Uris Purchase Fund and the Painting and Sculpture Committee 87.7. Photography by Sheldan C. Collins. Copyright by Pollock-Krasner Foundation/ARS, NY; City Landscape, Joan Mitchell. Oil on canvas, 80 by 80 inches, 1955. Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Society for Contemporary American Art. Copyright Estate of Joan Mitchell.]