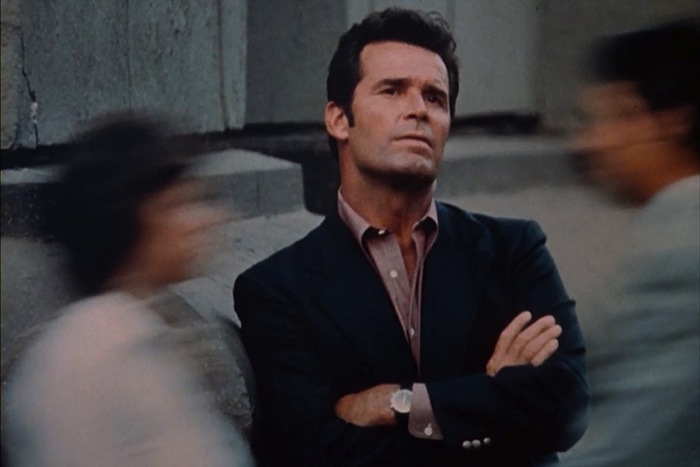

As I walk into James Garner’s suite at the Palisades Hotel in Vancouver, British Columbia, I suddenly feel as though I’m the Dude From the East accidentally strolling into the back room in Black Bart’s Saloon. There, sitting around a table in the kitchen, is Bret Maverick himself, surrounded by four other poker-playing rascals, and all of these boys are big. We’re talking teamster big, with hair that looks like windblown bushes and sweaters that bulge with muscles, and not your smooth, sinewy account-exec Nautilus muscles, either. No, these guys are North Country big, with muscle and flab and big, flat faces, and they’re all smiling at none other than Gentleman Jim Garner himself, who turns and looks at me with that Jim Rockford “Awww hell, Angel” smile and says, “Now isn’t this just my luck. Just when I’m getting ready to take these suckers for every dime they got in a fast little game of Jerry’s Rules, I have to do this damned interview. Well, hell, on the other hand, maybe we got us here what you call your one more basic pigeon. Get yourself a drink of wine from the box in there, Robert, while I finish up this hand.”

He’s up here filming Joseph Wambaugh’s novel The Glitter Dome for HBO, and Garner is all smiles as he invites me in. There is that born confidence man’s charm in his voice. “You get your wine, Robert?” Garner asks as he laughs and deals the boys another hand. “You know these journalists, they do like their booze.”

“Now just a minute,” I say. “Is this going to be one of these star-insults-the-press interviews?” Garner had already informed me that he does only one interview a year, and this is it. (“Hell,” he’d pointed out, “I don’t even eat with my press agent.”)

“No way, no way,” Garner says, smiling and winking and raking in the chips with his big, meaty right hand. “What we got here is an I-treat-you-like-a-king interview. We’re talking your basic royalty on the road. Man came all the way from that behavior sinkhole New York City to talk to me, boys, so I’ll have to do some work. I don’t know why anybody would want to know what the hell I have to say anyway, but as long as he’s here, we’re going to treat him right.”

“Just make sure you teach him Jerry’s Rules,” says Dave, a muscle-bound kid with a big, innocent face. “I still don’t understand that goddamned game.”

“In good time,” Garner says. “All in good time, Dave. Just make sure you get us out there to the location in that damned snow tomorrow, okay?”

“But let me tell you, comedy ain’t easy, son. Ask Paul Newman.”

“No sweat, Jim,” Dave says. “I can tell from the moon: no chance of snow.”

As the troops file out in their big, heavy snow boots I notice that the table is clear of money.

“Hey,” I say as Garner closes the door behind them, “don’t tell me Bret Maverick plays for fun.”

“Awww sure,” Garner says, “I don’t want to be taking their money. I work with these guys. They’re a great bunch of guys too. Hell, this crew, working with Stuart [Rockford Files] Margolin and Margot Kidder, that’s like old times. I’m getting to the age that if it ain’t going to be fun, then I’m just not going to do it. I been through enough craziness in this business.”

True enough. The man who emerged, along with David Janssen, as our finest TV actor, a southwestern working-class Cary Grant, has had to put up with plenty of insanity, in both his business and his childhood. The combined tensions of his crazy-quilt past and the impossible demands of series television have made Garner a worrier, given him ulcers and brought days when “gloom settled over me like a cloud.”

But like Bret Maverick and Jim Rockford, his television personas, Garner has learned how to get by on his own terms. “I’m a lead sinker in deep water,” he says. “I’m out of my league with those [business) people. I don’t understand them, and it’s very difficult for me to work with them. I’m a total outsider, but basically I leave it all behind me at the studio…. I grew up in the business with Janssen. We were old friends. I saw what the pressures and the drinking did to him. He drank to take off the pressure, not because he was a drunk, but in the end it all killed him. Even if you’re in great shape, series TV work will kill you—I’m talking twelve to fourteen hours a day. It’s not worth dying for.”

“I won’t do movies that glorify killers and bank robbers, like Bonnie and Clyde—and that was a picnic compared to what’s being filmed today.”

If Garner is known as the consummate TV actor, he has also made some thirty-five feature films in a three-decade career, most notably The Americanization of Emily (his favorite), Support Your Local Sheriff, The Great Escape and Victor/Victoria. And this year promises to be especially busy. In addition to HBO’s The Glitter Dome, scheduled to air in May, Garner will star with Shirley Jones in Tank, a feature film scheduled to be released this month about a soon-to-retire Army sergeant major who rescues his son from a sadistic small-town sheriff. There’s also talk of working with Mary Tyler Moore on a TV movie called Heartsounds, based on Martha Lear’s best-selling book.

Yet, as I remind him, critics have said that he’s spent too much time doing TV series work and that his success on the tube has never quite translated to the big screen. “First,” replies Garner, “I won’t do movies that glorify killers and bank robbers, like Bonnie and Clyde—and that was a picnic compared to what’s being filmed today…. I’ve always been fortunate that I’ve never been that down, and I’ve never been that hot. I’ve tried to stay a commodity that’s available for hire. I was never driven to be number one. I just hang in there, number six or seven, and watch ’em go up and watch ’em come down. Up and down, and I’ve done it for thirty years.”

If Jim Garner has succeeded in becoming the lovable, easygoing but tough humanist we’ve loved, the kind of guy you’d like to have as a big brother, it hasn’t been an easy trip. From the day of his birth, on April 7, 1928, in Norman, Oklahoma, things were not easy for James Bumgarner. His mother died when he was four, and his father, Weldon, a carpenter and carpet layer, was too busy—he was married four times—to be much of a father to young James. Or to Garner’s two older brothers, Charles, now a schoolteacher, and Jack, a golf pro and actor. To make matters worse, Garner’s old man married a woman named Wilma, who beat Garner regularly with switches that she’d forced him to cut from trees in the backyard; on several occasions she put him in a dress and had everybody call him Louise. After Garner rebelled and decked her with a punch—causing more family turmoil—Wilma finally hit the road. But by that time Garner himself was just about out the front door. He worked at a series of odd jobs—oil-field roustabout, carpet layer, carpenter and chauffeur to a traveling salesman who sold Curlee Clothes. The two of them, 15-year-old Garner and the milk-and-Scotch-drinking salesman, drove all over Texas, stopping at hotels and selling their clothes from the room. Garner made phone calls to prospective buyers, wrote up orders and tried to keep his boss from putting away too much Scotch.

Eventually, Garner drifted out to southern California, where he landed a job clerking and weighing vegetables at the A&P. He had an aunt living there who was convinced her big (six foot three inch) nephew was destined for the movies and sent a string of talent scouts around to the checkout counter. And his aunt wasn’t the only one who had big plans for him. Right before Garner went into the Army, a drugstore soda jerk named Paul Gregory, who himself had dreams of being a big producer someday, told him that he was going to be a star.

Now, as he sits in the top suite of the Palisades, overlooking the snow-topped mountains of Vancouver, Garner smiles at the memory.

“The thing is,” he says, sipping a glass of white wine, “everybody always thinks I had it tough. But it was all I knew. It didn’t seem that tough to me. I had to get out of the house a little sooner than most kids, and I had to put clothes on my back and get a job earlier, but maybe you’re better off having to do it earlier than later.”

“Still,” I say, “the way you talk about taking care of that guy you drove around Texas with is kind of touching. I mean, you were only 15. Usually at 15 a kid needs someone to take care of him.”

“I quit drinking when I was 26. I had this habit of trying to drink all there was, but I found out that the liquor boys could produce more bottles than I could down—not that it stopped me, in my drinking days.”

“Well, hell, I never thought about it that way before. Yeah, I can see your point. But then, I didn’t have much choice. Just like in the service. I got myself two Purple Hearts in Korea. First time, some shrapnel hit me in the eye, but it glanced off my helmet. Now, you love those—you don’t lose anything there. Second time, my infantry unit was overrun and practically everybody was killed. I got separated from my company. Walked eight miles, my knees torn up, my shoulder dislocated. We didn’t have any air panels or anything, so our own Navy jets came over the next day and just rocketed the hell out of us—thinking we were from the North—that’s my luck, being in the wrong place at the wrong time….”

When Garner says this, every aspect of Jim Rockford is in place: the chagrin at life’s absurdities, the understated humor of the victim and the manly determination to keep on keeping on, no matter what the odds.

“…Got me a nice white phosphorus burn from that one. Anyway, me and another guy, a South Korean, walked the hell out of there, eight miles behind enemy lines. They never did give me my Purple Hearts. Not until I finished making this movie Tank. It coincided with the Army’s commemorating the 200th anniversary of the Purple Heart, so they finally gave me the actual medals. Hell, they’re only thirty years late.”

Garner chuckles and drinks his wine.

“Can’t drink too much of this,” he says, reaching back and rubbing his head, showing the effects of his third glass. “I quit drinking when I was 26. I had this habit of trying to drink all there was, but I found out that the liquor boys could produce more bottles than I could down—not that it stopped me, in my drinking days.”

He put a cork in those drinking days when he got back to Hollywood. While driving down LaBrea one day he happened to see a big sign emblazoned with PAUL GREGORY AND ASSOCIATES—Paul Gregory the soda jerk now had two plays on Broadway. “I still didn’t really want to act,” Garner recalls. “It was never an all-consuming passion. But I thought, I don’t have any degrees; what the hell am I going to do, lay carpet the rest of my life?”

Gregory got him into the national touring company of The Caine Mutiny Court Martial. Garner played one of the six silent judges, never uttering a word for 512 performances. But he got to work with Lloyd Nolan, John Hodiak and, most important, Henry Fonda.

When Garner speaks of Fonda today, there is a glow in his face that has nothing to do with the wine. He obviously loved Fonda, perhaps like a father. “You can’t be around somebody that good without learning something. I’ll tell you one thing I did get from him, I hope, and that is, he treated everyone equally. He was good to people.”

“I had a feeling about Maverick from the beginning,” he has said, “and damned if it didn’t go. They put us up against Ed Sullivan and we killed him. Hell, it was a cult thing.”

Garner would later work with another acting legend, of sorts. “Oh, Ronnie, Ronnie,” he remembers, laughing. “Isn’t he wonderful? Listen, I was the vice-president of the Screen Actors’ Guild when he was its president, and we used to tell him what to say. He can talk around a subject better than anyone in the world. He’s never had an original thought that I know of, and we go back a hell of a lot of years. Do you realize I could have been your president?”

I casually ask Garner if Reagan used to get much respect from his acting peers.

He gives me that sly look before answering, “You mean Sonny Tufts and those guys?”

The next few years brought the two most important events in Garner’s life: his marriage and his first TV series.

Garner was 28 when he met Lois Clarke, an aspiring actress. He married her and began to take care of her 6-year-old daughter, Kimberly, who was successfully fighting polio. (They have another daughter, Gigi, who is now 26 years old.) Garner talks about assuming this responsibility the same way he talks about helping the Scotch-drinking Curlee Clothes salesman, as if it were no big thing, and it suddenly occurs to me that this is one of the secrets of his appeal: Jim Rockford might seem like a charming loner, wary of the fray and self-involved, but when the chips are down, he’s up there on his battered white charger fighting like hell.

That sense of responsibility is obvious when he talks about his marriage of twenty-seven years. The Garners are a very private couple, and Jim is happiest staying in his magnificent home in Los Angeles and watching sports on TV. (He’s a sports nut—he used to drive a race car, played football in high school and now can be seen cheering on the sidelines with the Los Angeles Raiders.) He gives most of the credit for their long marriage to Lois, “who’s put up with me all these years.” But he adds, “When I make a commitment, I make a commitment, and we work it out. It does put a strain on our marriage if I’m kissing a beautiful leading lady all day and then go home to my wife. She’s got to be understanding. I remember one time I came home and she said, ‘Are you tired?’ and I said, ‘Yeah, I’ve been kissing Julie Andrews all day and my pucker’s tuckered out.’ She about killed me.”

In 1957, Garner did the pilot for a TV western series called Maverick. “I had a feeling about Maverick from the beginning,” he has said, “and damned if it didn’t go. They put us up against Ed Sullivan and we killed him. Hell, it was a cult thing.”

I tell Garner how much my childhood friends and I loved the show, that I can still remember baseball games breaking up in the alley so that all the kids could run home and watch it. “I can even remember one of the episodes,” I tell him, “when Maverick just sat up against a pole in front of the sheriffs office and whittled. He’d been conned out of some money, and people kept asking him what he was going to do about it, and all he said was—”

“‘I’m working on it,’” Garner laughs. “More people remember that episode than any other one. It was called ‘Shady Deal At Sunny Acres,’ and the director gave me the choice of playing the guy who runs around arranging the sting or the guy who just sits and whittles, and I knew it had to be the whittling scene for me. Jack Kelly, who played my brother Bart, got the other part.”

“Hell, they said Gary Cooper couldn’t act, that he only had a great personality. Well, let me tell you, if you can get in front of that camera and have people like your personality like they did Coop’s, then who cares what the critics say?”

There’s a bit of a competitive edge in Garner’s voice here, just a touch of the southern good ol’ boy who has put one over on the city slickers.

“But it seems to me,” I say, “that that role is the essence of your acting. You sit and react, and remain cool, or wry, while everyone else runs like hell all around you.”

“Hell, they said Gary Cooper couldn’t act, that he only had a great personality. Well, let me tell you, if you can get in front of that camera and have people like your personality like they did Coop’s, then who cares what the critics say? What I’m about is character—creating character. Robert Montgomery was like that. He was a wonderful comic actor. But he never got that much credit… like me.”

Garner gives a nervous laugh, embarrassed at having tooted his own horn.

“So often the guys who get all the credit,” continues Garner, “are the ones you see chewing up the scenery. Acting up a storm. I still think the real actor is the one you don’t notice acting.”

“A buddy of mine told me you were the working man’s Cary Grant,” I say. “But the critics might not see it because you’re doing comedy.”

“Hell, I like that,” Garner smiles. “But let me tell you, comedy ain’t easy, son. Ask Paul Newman. Paul’s made a couple of comedies. He was okay in them, but he doesn’t really have the comic timing.”

He smiles his slow, charming smile and takes a last sip of wine.

The next day, after a morning of playing backgammon and shooting craps with Garner and his stand-in/best buddy for thirty-seven years, Luis Delgado, I’m in Garner’s van, heading across Vancouver for a graveyard scene. It’s getting cloudy and dark out, and Jim Garner is talking about his past, honesty and Hollywood.

“You see,” he says, flipping down his shades and looking out at the streets, “I was raised in a place where a man’s word was his bond. Oklahoma. Oh, sure, we had our hustlers there too, but for the most part people were honest, took care of one another. If a man lied, it was usually transparent, because the norm was to tell the truth. But in L.A. people live the lie. They’ll look you right in the eye and lie to you. They lie even when there’s no reason to. I don’t understand those people. They’re too devious for me. I don’t trust any of them anymore. They’ve taken the heart out of it for me, and I used to really love this business.”

I ask if he’s referring to the multimillion-dollar lawsuit against Universal over The Rockford Files, in which Garner is suing to retrieve profits from the series.

“Some guys are professional, too professional, so they get slick and use the same old tricks. But Jim is working on making it real, rougher around the edges.”

“Yeah, among other things. Our company, Cherokee Productions, was supposed to get a 38 percent share of the profits. We brought that series in only seven days over schedule in five and a half years—no other television show can match that record for even one year. The show was a big, big hit. I figure they’ve stolen about 25 million dollars from me, and that’s a hell of a lot of money.”

He then begins to patiently explain the elaborate and varied tricks accountants can play to somehow conclude that a show that was a hit for six years, and is still in syndication, didn’t earn a dime and is, in fact, $9.5 million in debt. “I don’t know if I’ve got the guts to resist the out-of-court settlement when they offer me a whole bunch of money to call it off,” Garner admits.

“Is it worth all the mental aggravation?” I ask.

“Now you’re talking like them,” Garner says, and there’s steel in his voice. “They figure to wear you down. But damn, it’s not just that they have my money, it’s also the principle of the thing. It’s wrong.”

There’s a finality to the word wrong, and I have to smile. I think of Martha, a southern lady I know who’s a secretary in Baltimore. When I told her I was going to interview James Garner, she said, “You tell him he has an honest face and he’s the only damned movie star I’d move back into a trailer with, you hear?”

At a freezing suburb outside Vancouver that has been dolled up to resemble L.A., Garner gets dressed to play a tough scene. He plays a burned-out detective in The Glitter Dome. A buddy has been killed, and Garner has to stand at the funeral in the “rain” (supplied by off-camera hoses with sprinklers attached) and look as though he’s been beaten down by exhaustion and drink and fatigue. As I wait for him to change his clothes I talk to Stuart Margolin, the director. He’s best known, though, as Angel, Jim Rockford’s squealing, bitching, cowardly but lovable buddy-nemesis on The Rockford Files.

We huddle up in a truck cabin, eat some cold chili and talk about Garner’s acting.

“He’s getting better and better as an actor,” Margolin says. “I mean, some guys are professional, too professional, so they get slick and use the same old tricks. But Jim is working on making it real, rougher around the edges. The next ten years should be interesting. He’s turning the corner into what you call the leading character man. He’s going for more experimentation, and he’s brought a reality all his own to this part. You watch these scenes, and you’ll see what I mean. This isn’t Maverick.”

A few minutes later I watch Garner standing on the freezing infield of a Vancouver playground. The water is coming down on him, and the camera closes in, and there is pain, disgust, weariness, that does look different from anything I’ve seen from him in the past. It’s the face of an older, hurt man, and I think that maybe, unconsciously, he’s using the lawsuit against Universal to summon these feelings of disgust and anger. But whatever is pushing him forward, it’s obvious that he’s going for something different here, something that reaches the gut in a deeper way than charm.

Now, in the darkness, we’re riding across Vancouver. Our friend Dave the driver has stopped by the van and assured us there’s not going to be any snow, but it’s already falling, great thick flakes. All the world’s a great, soft stage, and only the hum of the van’s engine cuts through the night as Garner rides shotgun and Luis and I sit in the back in a warm, comfortable and friendly haze.

“I read somewhere that you never let your price get too high for films,” I say. “Why’s that?”

“Well,” Garner says, turning around and putting one leg up on the tool hump, “in Hollywood they have this terrible thing: You can’t ever let your price go down. When Lee Marvin put his price up to a million dollars a picture, he found it harder to get work. I didn’t want to cut myself out of work, so I never let it get that high. I mean, if a picture is really good, I’ll do it for practically nothing, take a little profit on the back end.”

“Have you ever really done that?” I ask.

At 55, his knees are shot, the result of several operations and arthritis, but otherwise he looks great, and later I ask him if he works out at all. After an appropriate pause, he says, “The only time you’ll see me jogging is if somebody is chasing me—and he better be big, or I won’t even run.”

“Sure. I did it for Bob Altman on Health, which is a pretty good though hardly anybody saw it. But I did it because I wanted to work with Altman, and Betty Bacall and Glenda Jackson, and Carol [Burnett] and Cavett… yeah, even Dick Cavett, he’s my buddy. I talked to him the other night, and I confessed to this little trick we played on him. See, Betty Bacall wrote up this diary, invited Cavett over to her condo and left it out especially for him to see. Then she goes into the bedroom, and she leaves the diary there, wide open. Well, he can’t resist taking a peek, and suddenly he sees his name. Now he’s got to read it, and it says something like, ‘Well, Jim Garner is such fun, and Carol Burnett Is a ball and Glenda Jackson is wonderful, but Dick Cavett dresses like a 14-year-old and is so silly.’ And it just crushed him. Well, he finally admitted when I talked to him the other night that he had seen the diary, and I say, ‘Did it ever occur to you that that diary was put out there so you would see it?’ And he says, ‘You wouldn’t…. I went to therapy over that!’ And I said, ‘Well, Dick, maybe I would and maybe I wouldn’t!’” Garner slaps his thigh and laughs hard and loud. The kind of joke Bret Maverick might like.

As we arrive at the big studio on the top of the snow-covered mountain in Vancouver, Garner is talking about the first time he met his buddy Margolin and about his favorite TV role.

“We had this show called Nichols. It’s the best work I’ve ever done, about broke my heart. The show was set at the turn of the century, in Nichols, Arizona, and I played a sheriff who rode a belt-drive Harley Davidson and refused to carry a gun. Wore jodhpurs and cavalry boots, and Stuart played a variation of the character he later played on The Rockford Files. In Nichols, though, he was really the most back-stabbing, irritating sneak, and he was my deputy. Margot Kidder was in Nichols, too, and she was wonderful.

“God we had talent on that show. Anyway, we were dead the first night we showed the pilot to the Chevrolet people in Detroit, because some executive’s wife didn’t like It. She said, ‘Well, that’s not Maverick!’ Well, of course it wasn’t Maverick! It was better than Maverick, humorous, with social satire. But we got preempted eight times out of twenty-four shows because of Nixon running for election. Then they moved us up against Marcus Welby, and we ran even with him, and he was the number-one show in the country. I don’t think we ever got below a 35 share the whole time. Hell, the show lasted one year, I swear to you, if they would have It on another year, it would still be running today. It was just too damned original.”

Garner now walks in from the blizzard to play a scene in which he’s walking through a daytime L.A. drizzle. He puts on his L.A.P.D. overcoat and slides into the makeup room. Susan, a makeup girl, affectionately starts in about Garner’s hair.

“It’s getting so long, dear.”

“Well, darling,” Garner says, “I know you’ll make it wonderful.”

It’s obvious that all the girls in the makeup department are crazy about him, each of them going out of her way to make him comfortable, bringing him mints (Garner is forever asking people for mints) or hot chocolate. Garner has such an easygoing manner, and there is never a hint of his demanding anything. Indeed , earlier today he mentioned a famous star whom he detested because he picked on little people on the set. “I won’t tolerate that,” he says. “My lawyer used to call me Crusader Rabbit! Bullying is not acceptable.” The line sounds very much like something one of Garner’s heroes, John F. Kennedy, might have said.

“Earlier today I watched you do that scene at the graveyard,” I say, “and you looked an older, weary man. Do you worry about getting old?”

“Nah, I think young.”

“I watched you on Maverick when I was 5,” Susan says, and Garner playfully gives her a punch on the jaw.

“She’ll do it to you every time,” he says. “Sneaky.”

At 55, his knees are shot, the result of several operations and arthritis, but otherwise he looks great, and later I ask him if he works out at all. After an appropriate pause, he says, “The only time you’ll see me jogging is if somebody is chasing me—and he better be big, or I won’t even run.”

“What about immortality?” I ask as we trudge from the makeup truck to the studio in the deepening snow.

“What about it?”

“Is it any… consolation?”

“Hell, no, not one whit. They could burn all the film tomorrow and I wouldn’t care. Listen, I’d rather be remembered in literature, anyway. Yeah, I was mentioned in Myra Breckenridge. Gore Vidal wrote that his hero had ‘inspected all the cowboy heroes’ asses, from the flat ass of Hoot Gibson to the impertinent, baroque ass of James Garner.’ Hell, I can be remembered for that.”

We both laugh, and Garner shakes his head.

“Man, I had to go look in the dictionary to figure that one out.”

“And what did it mean?” I ask.

“I don’t know,” Garner says as we walk into the studio, “but it sticks out and it’s got dimples.”