Karl Wallenda plunges to his death, and the man beside me booms out “Gawd!” In the slow-motion TV replay, Wallenda’s last-second grab for the wire seems to sum up everyone’s will to live, in one gesture. Then he falls. It’s a horrifying sight, but my host—a tall man in a Stetson and black shades—feels it more deeply than I do: Hank Williams Jr. knows about falls.

We’re sitting in his den in backwoods Alabama, where he’s unwinding after a grueling tour of California. Like his father before him, Hank is a singer, and even his speaking voice borders on song. He commands a range of Southern vocal tricks, from a playful falsetto crack to a sage-like basso profundo, with separate controls for drawl, speed and irony: Each story becomes an aural roller coaster ride. The one he tells now is especially bumpy.

It was August 8, 1975. He’d just recorded a landmark country-rock album, Hank Williams Jr. & Friends, that signaled his emergence from his father’s shadow. Climbing a Montana mountain with a guide and his son, he stood at the Continental Divide and looked out.

“It takes a while to get up to 9,000 feet. We were lookin’ over at Salmon, Idaho, right by a brass stake that marks the Divide. We were on Ajax Peak, which is like a knife edge—you’ve really got to climb around to get there.

“We’re lookin’ for mountain goats, way up past the tree line. And finally we started back down, crossin’ some pretty rough terrain. And I stepped in the guide’s footprint, but it had loosened, and I got caught in a snow slide.

“It was just like fallin’ out an airplane—straight down. So down I went, slidin’ headfirst on my back. Emotionally, I just froze inside. No feelin’. Just shock. And I thought: You’re dead. You’re just gonna splatter on the rocks.

“Then, after that thought got out of the way—all this is goin’ on within seconds—I flipped over so I was slidin’ headfirst on my stomach, and I tried to get that .44 out of my shoulder holster, tried to dig that long barrel into the snow, to try and break the fall. ’Course that was a joke.

“Then I swung my feet down under me as I felt the first little rocks hittin’ me, and I decided that the first boulder I hit, I’d just kick out with all my might. Bump, bump, bump, I felt the rocks gettin’ bigger, I was bouncin’ across ’em. So I drew up my legs and kicked out.

“Dick [the guide] was watchin’; he said it looked like a guy comin’ off a ski jump. Then it was a free fall, with me flippin’ over. As I’m fallin’, I see this huge mountain lake, and I said, ‘I’m gonna try and land in that lake.’ ’Course that would’ve killed me right away.

“Finally, I hit that snow like a swan dive. There was a boulder stickin’ up through there, and I just hit it straight on, headfirst. It just literally split my face in half. It started right at the top of the hairline, split me right exactly between the eyes, down the left side of the nose—stopped at the chin, although that was broken too …

“Came to a rest slumped over in a sittin’ position. First thing I done was to look at my hands—you always look at your hands, for some reason—and I couldn’t see anything wrong! I thought, hell, I’ve made it! And I started gettin’ my hands up into my head, and I don’t have any nose, any teeth—I don’t feel any head. It’s just all a hole, and I’m puttin’ my fingers up in it. Just a hole from the lip all the way up, and I’m puttin’ my hands inside it … grabbin’ hold of my brains and all this gobbledygook.

“And Dick gets down there—’course there was a lot of snow, retardin’ the bleedin’—he starts tearin’ my hands away. I’m sayin’, ‘What is it, what is it?’ And he says, ‘It’s your nose, it’s your nose.’ He said it was all he could do to keep from throwin’ up. And I saw that he was cryin’, and he’s a pretty tough old boy.

“Then I jumped up, with this big surge, and I said, ‘I’m walkin’ out of here, let’s get to the Jeep.’ Then, of course, the blood came out in torrents, just like turnin’ on a water hose, pumpin’ out with every heartbeat. And my right eye’s hangin’ out. And Dick keeps sayin’, ‘It’s your nose … ’ Then I just made two or three steps and piled up. So Dick grabbed all this stuff hangin’ out and just shoved it back into place, and it made a terrible sound—all this flesh and bone crunchin’ up. Then he tore his shirt off, ripped it up, and wrapped the stuff in place as best he could. No tellin’, no way to describe what he seen.

“Now I’m gettin’ cold—real cold—so he made a rock enclosure around my head. Now the little boy gets down there, and ’course he’s cryin’, ’cause he’s seen this terrible fall, and he wants to go for help. But Dick just grabs him and shakes him and tells him to just keep me talkin’, kick me in the back now and then to get that junk out of my mouth. And Dick goes lookin’ for help.

“Now I’m alone with this boy, and he’s stunned. That’s when the bad period set in, the give-up period, when I just knew that I was dyin’. And I’m lyin’ there, lookin’ out with one eye at this great scenario, these beautiful snowy mountains—very peaceful, if you weren’t in my situation … And I thought: This is death.

“And I said to the Lord: I’ve wanted to die a lot of times. But I wanted it to be onstage, or an overdose in a car—you know, some nice musical death. Not like this, alone in the snow with a little boy chatterin’ on beside me.

“By now he’s talkin’ a blue streak—his coon dog’s the best coon dog in the world, and he’s gonna win a prize at the fair, and he loves to go fishin’ … And I’m thinkin’ about my own little boy, and about Becky, and the guys in the band, the bus, my mother, my grandfather—the whole thing …

“But then all that’s gone, and it’s just here comes death, whatever it is.

“Now for some reason my eye—the one still in my head—caught sight of these two rings on my hand, the H and W, my initials. And for some reason, seein’ those rings made me think I could live. And I started poundin’ my hand in the snow, poundin’ with every heartbeat. When they finally got to me, I’d dug a crater two feet deep in that snow. Two and a half hours went by that way.

“But now the boy’s still ravin’ on, and I’m tryin’ to answer him—couldn’t understand me ’cause of the gook in my throat, but I said, ‘I’m not givin’ up here, I’m gonna fight this thing.’

“Now his daddy’s at the foot of the mountain. And he yells up to the boy, ‘Is he still talkin’?’And I wanted to jump up and holler, ‘Hell yes, get up here!’ I could see him down there, and he looked like a giant—some muscles in my brain had been strained, affectin’ my sight in the eye that was workin’, and everybody looked like a giant to me. Dick looked like he could just reach up the mountain and carry me away himself.

“He hollered up, ‘The helicopter’s coming!’ Now he’d found a forest ranger, by pure luck. Otherwise he’d have had to drive to the ranger station, which was 27 miles away.

“Then the medics came, and it was in with the Demerol, in with this and that. Wrapped my head in bandages. And these rescue guys had this cocoon-like stretcher, and they had to carry me.

“And it’s hurtin’ now. Bad. And then I realize I’m goin’ on the outside of the chopper, it’s a one-man machine. And my cocoon is clamped to the outside. Up goes the helicopter, and I’m right out there in the wind, on the struts. And I’m wonderin’ if I’m gonna die in this cocoon hangin’ off a helicopter.

“But it didn’t take long before we set down on a ranch. They got me right into this Cessna, did some more work on me there, and off we go. We’ve still got this 100-mile trip to make.

“We land in Missoula, and it’s right into another helicopter. This is nearly five hours after the fall. They’ve got bottles and needles hangin’ over me. And we set down on the helicopter pad, and we’re inside the hospital.

“I never lost consciousness the whole time. The doctors said that had a lot to do with me livin’.

“And they started cuttin’ off my clothes, my shoulder holster, and they went to cut off the cross I wear around my neck. I started yellin’, ‘No! Don’t cut that cross!’ And that’s the last thing I remember before I went under. And later I had all that stuff—clothes, holster and cross—sewed back together.

“Four doctors operated on me for 7½ hours. And as soon as I woke up in that hospital bed, I thought: The hard part’s over. Now the healin’ can begin.

To be born Hank Williams Jr. in 1949 was to be the namesake of a god. His father was—and still is—adored with fervor throughout America. His first hit, “Lovesick Blues,” established him as the greatest draw the Grand Ole Opry ever had. Through his songs—“Your Cheatin’ Heart,” “Jambalaya,” “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry”—he became the down-home poet of hell-raising and grief. Add a death at 29 from speed and alcohol, and you have all the ingredients for an instant myth.

The last few years of his life were a boozy fog, marked by a divorce from his wife, Audrey. Although still idolized, he was increasingly tormented by the forces that shaped his lyrics. His one sustaining joy was Hank Jr., who was three years old the night his father died in the back seat of a new ’52 Cadillac.

When asked what he remembers of Hank Sr., the son at first responds with a brusque “Nothing.” Then he ponders the question for 30 seconds. “Wait—just a snapshot image in an airplane, once. And backstage at the Opry—I knocked something over … ”

But if his memories are vague, there were always thousands of people to fill him in. The Hank Williams legacy was his, whether he wanted it or not.

He was raised on the belief that loneliness was in his bloodline, along with music and alcohol. As if the “lovesick blues,” like black lung, was a disease linking the generations.

When he was eight years old, he was thrust into a career as a professional specter, playing his father’s songs for crowds of necromantic drunks. Red Foley, the Opry star, would sit backstage with the child and tell him: “You’re a ghost, son, nothin’ but a ghost of your daddy.” His mother would hold him close and say virtually the same thing.

“I don’t want to be a legend, I just want to be a man.”

For months at a stretch he would tour the honky-tonk circuit, rooming with legendary wild men like Johnny Cash and Jerry Lee Lewis. He’d watch Cash stuff cherry bombs down motel toilets and rig booby traps for the maids; he’d serve as mascot for troops of stoned musicians; and he’d steal every show because his name was Hank Williams.

Then he’d go home for a while and sit in class with the other third graders.

“It was a bit schizophrenic,” he says with a wry smile. “At first, I thought bein’ Hank’s boy was the greatest thing in the world—a ghost of this man that everyone loved. They think I’m daddy—how wonderful. Mother’s smilin’, she’s happy, money’s rollin’ in, manager’s happy—seemed ideal. Then, round about my teens, it all hit me at once.”

One can only try to imagine how adolescence hit Hank Williams Jr. When he was 16, he had a number-one record on the C&W charts—“Standing in the Shadows,” a recitation set to music. MGM, his record company at the time, had him overdub his voice onto Hank Sr.’s songs, and released two albums that featured a living teenager harmonizing with his dead father.

A heavy drinker since his mid-teens, he embarked on a nonstop bender through his early 20s.

“It was the whole country music syndrome. I got to where I didn’t have any more hangovers—woke up drunk, went to sleep drunk.” During this period he also co-starred in a movie, A Time to Sing, with Ed Begley, did the soundtracks for several other films, and married for a second time.

He was rich, sweet-faced and an idol by proxy. But in addition to his Jack Daniel’s habit, he’d become addicted to Darvon. He seemed bent on replaying his father’s melodrama—live hard, die young and be played by George Hamilton in a cheesy film biography. (The movie, Your Cheatin’ Heart, has grossed millions over the years; Hank Jr. did the soundtrack.) With a myth for a father, and a classic stage mother, he was caught in a Freudian squeeze play.

In 1973 he snapped. “Booze, sleeplessness, pills, depression, it just got to be too much.” Just as his father had done 20 years before, he began missing gigs, acting crazy, inching closer to ruin.

“I was still havin’ to do shows as daddy. I’d sit home listenin’ to Chuck Berry and Fats Domino, thinkin’ of musical concepts myself, but I’d still have to play those lonesome songs of Hank’s—and they were hittin’ pretty close to home. Marriage bustin’ up—I was supposed to be this big success, but where were the friends? Where were the lovers? I guess it all ganged up on me. So I tried the check-out route.”

In a 1974 song, “Getting Over You,” he describes his attempted suicide: “I got some pills from an old doctor friend;/The bottle said one every twelve hours for the pain./You know this pain I feel ain’t small,/That’s why I took them one and all./It was something I had to do/To get over you.” (To get over whom? He says it’s addressed to his first wife, but the lyric makes sense as a message to his father, too. In any case, friends got his stomach pumped in time.)

After his suicide attempt, he sought help from a Nashville psychiatrist, not an easy step for a man trained in macho loneliness.

“Well, I’d been huntin’ with him, so I trusted him as a man. And it was pretty much life-or-death at that point.”

The psychiatrist diagrammed a deadly triangle that had kept Williams trapped and depressed: his mother, widely described as a hard-drinking, haunted woman who exploited her son; his manager, who resisted Hank’s creative impulses; and the city of Nashville. All conspired to keep him a ghost.

“The doctor said, ‘You’d best get the hell out of this town. Ain’t no good times for you here.’ So I did—moved down to Cullman, Alabama. Started havin’ some fun. Realizin’ that self-pity is bullcrap.

“Pain is somethin’ you get to leanin’ on. I fell into that trap of thinkin’ I had to suffer to create. Finally I realized: Hell, I don’t need it that bad. No matter how good the songs that might come of it, nothin’s worth that kind of pain.”

After listening to numerous writers who treasure their hard-earned angst above all else, and who constantly quote the old Rilke saw, “I don’t want to exorcise my demons, for my angels might leave too,” it’s a pleasure to hear the cult of despair ridiculed—especially by a writer as gifted as Hank Williams Jr.

“Hank is as fine a songwriter as you’ll find in country music today,” says Michael Bane, editor of Country Music magazine. “Like Willie Nelson—his only equal—he’s got that intuitive poetry that makes you think, I’ve been there, and it happened that way.”

That poetry comes from a struggle—to carve a selfhood from a block of legend, to deal with pain without self-pity.

“Look at some of these rock stars, throwin’ TVs outta windows to show how artistic they are,” Hank snorts. “It’s the difference between actin’ crazy for publicity, and bein’ crazy ’cause you just can’t help it. Well, I figure I’ve put in my time. Let somebody else sing the blues.”

Friday night. A redneck civil war rages in the Palomino, L.A.’s country music venue. Roughly half the patrons are bouffant-and-sagging-jowls types who’ve come to hear a seance, a slavish evocation of Hank Williams Sr.; the other half are spaced cowboys who want Hank Jr., rock, blues and all. The schism widens as the band moves into a signature tune of Hank Sr.’s, “You’re Gonna Change (Or I’m Gonna Leave).”

It’s the old lyric, all right—a typically Williams mix of plaint and whimsy—but it’s done in a grinding, Chicago blues adaptation that strikes a bouffant next to me as sheer heresy.

“Shoot, he’s got it all niggered up,” she whispers in disgust to her husband. Meanwhile, the cowboys are stomping and yipping their approval.

Hank’s voice is a wonder—it hits a high, keening note and holds it for eight bars, then nose-dives into a cavernous bass without hesitation. As a pure instrument, his voice far surpasses his father’s; few white singers can compete with him. (One voice teacher has compared his singing to opera star Luciano Pavarotti’s.)

Like all instinctive artists, he leads with his subconscious.

He does Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama” as a tribute to several of that band’s members who died in a recent plane crash. It’s a fittingly rowdy eulogy, with Hank ad-libbing and the band rocking out.

Hank sings with his head tilted back, sunglasses dazzled by the baby spotlights; he looks, and sings, like a blind man. (Since the accident he’s worn a Stetson to hide a dented forehead, and shades to hide eyes that don’t match.)

Mayday, mayday—there’s danger at a table right in front of the bandstand. Two drunken couples are passing their multicolored drinks around like joints, with predictably bad results. They’re alternately shaking with the music and slumping in their chairs, fixing Hank with the hopeless fish-eye stare of the truly wasted.

As he finishes “Stoned at the Jukebox,” a great outlaw anthem from the Friends album, one of the women springs back to life. “Hank!” she screams. “Play ‘Cheatin’ Heart’ for Hank and Audrey!” With this, she digs a crumpled twenty from her purse and flings it onstage. Hank ignores it, but more bills come sailing up from the crowd, many with requests scribbled on them. Napkins inky with requests fly onstage. People with requests fly onstage.

“Gawd, I hate that shit,” Hank says later. “Sometimes I kick the damn bills off the stage, hopin’ to head it off. And sometimes I just stop and lecture ’em. I say, ‘Look. At one point in my life I was programmed to be my daddy. But my daddy’s career is doin’ pretty good, so how ’bout lettin’ me work on my own?’ If that don’t work, there’s usually a few cowboys in the crowd to make the loudmouths shut up.”

This time, however, he responds to the shower of twenties with poetry—his most poignant song, “Living Proof.”

I’m gonna quit singin’ all those sad songs,

’Cause I can’t stand the pain—

Oh, the life I sing about now

And the one I live is the same.When I sing them old songs of Daddy’s,

Seems like ev’ry one comes true.

Lord, please help me, do I have to beThe living proof.

His voice, rich and sonorous, coaxes extra syllables from “living” and “proof,” drawing more rebel cries from the aficionados. The bouffant next to me pouts in silence.

Why, just the other night after the show

An old drunk came up to me.

He says, “You ain’t as good as your daddy, boy,

And you never will be.”

Then a young girl in old blue jeans

Says, “I’m your biggest fan”;

It’s a good thing I was born Gemini

’Cause I’m livin’ for more than one man.*

When he reaches the last line, both factions—his father’s and his—suddenly roar in unison.

Hank Williams, also known as Luke the Drifter and Old Lovesick, fathered Hank Williams Jr., aka Luke the Drifter Jr. and Bocephus.

As far as Hank Jr. can remember, “Bocephus” was the name of a hillbilly comedian’s puppet in the Grand Ole Opry. In 1951 and 1952, during Williams’ greatest stardom, little Hank would sometimes watch the wild shows at Ryman Auditorium. He was entranced by the dummy. So his father, having already named him after himself, renamed him after a puppet.

It’s best to cast a wary eye on symbols when you’re dealing with real people’s lives. Bocephus might also be, Hank Jr. says, “just some silly hillbilly name.”

Now the band’s warming up the crowd, beginning the second set. Chris Plunkett, the bass player, sings a country rock call-to-arms, “The South’s Gonna Do It.” He sings it with deep conviction, and the crowd hoots him on, never suspecting that this drawling Johnny Reb is a jazz composer from Asbury Park, New Jersey.

After three songs they introduce Hank. Back onstage, fighting a high fever and flu, he starts out ferocious. He’s got that hell-raising mania that punk bands counterfeit, a roadhouse urgency that precludes slickness.

It’s so easy to milk pathos in C&W bars—all it takes is a few songs that Hank describes as the “my-darlin’-left-me-so-I-got-drunk-drove-home-and-ran-over-someone’s-little-girl” kind. For the most part, he resists this temptation, going after ecstasy instead. He seems to want to squeeze his whole body through the microphone, into some wilder land. Sometimes his lip, permanently numb from the fall, actually curls around the mike, and he has to pull his face away.

And sometimes he falters. Never scrupulous about tuning his guitar, he’s capable of playing an entire song in the key of X, loud. And when his energy sags, the act deflates instantly, as it does now in mid-set. Three or four tunes drone by in a stupor. Hank’s major problem as a performer is also his strength: Like all instinctive artists, he leads with his subconscious. But in an era when music is market-tested, shrink-wrapped and sold like deodorant, a few dull stretches and discordant notes seem a small price for authenticity.

By the end of the set, he’s got his grin and élan back in place, and he’s singing with the power of a Ray Charles, rocking through “Jambalaya”—“Son of a gun, we’ll have big fun on the bayou.” The band rips into the last descending chords, and Hank’s already moving through the crowd as the ovation begins.

A would-be groupie jumps up and grabs her idol in a half-nelson.

“Ah’m gawna put somethin’ on yew alcohol cain’t rub off!” she wails. Hank staggers a few steps with this doped-up albatross around his neck, then gestures to Albert, his road manager. It takes all of Albert’s considerable strength to pry her loose.

At the front table, the drunken foursome is still yelling for “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” even though the band’s already packing up and scanning the floor for loose waitresses.

Welcome to the Motel California: Howard Johnson’s in North Hollywood. In a working year, Hank spends 150 to 200 nights in motels like this—a toilet on perpetual flush, Art Drecko lamps with switches hidden in unlikely places, elevators where the air is so denatured that it’s like riding in a giant menthol filter.

We meet first on neutral turf, his manager’s room. Becky, his wife of a year, and several associates are there to run interference: After 25 years of being grilled about his father, he’s initially nervous at interviews.

“Say Jawn,” says J.R. Smith, his manager, “y’all bein’ a writer, y’all must know this Paul Schrader fella?”

Schrader, who wrote Taxi Driver and directed Blue Collar, has conferred with Hank Jr. about doing a new film biography of his father.

“That’d be a real good lick,” says Hank. His enthusiasm is understandable: How would you like to remember your father as played by George Hamilton?

Without seeking it, we’re into the father-son question. “See, the record companies tell me I’m writin’ too personal when I talk about my relation to daddy,” he says. “But every town we play at, some young person comes up and says, ‘I had the same routine with my father.’ So it seems like it’s pretty universal.”

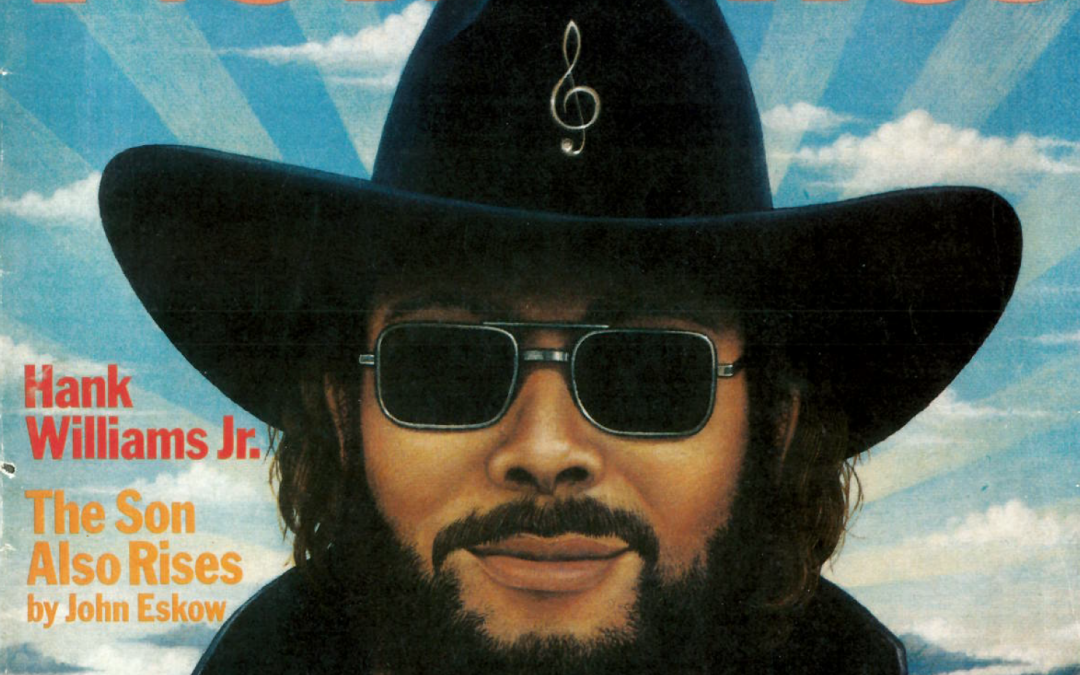

Outside, the blond canyons look down at the sea. Hank’s wearing his gray high-rise Stetson and denim, a cowboy in a long black limo, cruising L.A. The sun glints off the diamond clef above the hat brim, gleams on the ever-present shades.

We’re headed for Nudie’s, the Paris of redneck couture, the Hollywood shop that’s draped rhinestones around everyone from Elvis Presley to Elton John, by way of Dolly Parton. Albert and Becky shift uneasily as we approach—Hank’s been known to buy outfits he doesn’t need at Nudie’s, and they’re wondering what new extravagance he’s got planned.

(One point about Hank Williams Sr.: In addition to the long shadow he left for his son, he also left Hank Jr. a share of his royalties—something like $250,000 a year.)

Nudie himself greets Hank at the door. Nudie, at 75, is American weirdness at its zenith—both larger than life, and smaller. A wizened Brooklyn-born Jew in a Stetson of his own, wearing one black cowboy boot and one yellow one, he clearly revels in the role of Crusty Old Bastard.

He greets Hank like a beloved nephew, which, in a sense, he is. Hank Sr. was a close friend of Nudie’s, and bought all his outfits at the shop; his skeleton now reposes in a Nudie burial suit. Nudie remembers “little Hank” from his crib days.

“I made that boy his first rhinestone suit when he was two,” he says, ordering an employee to dig up a photo. “Yes sir … they used to send his daddy out to me for drying out. Sometimes we’d just both get wet.”

Among the 2,800 photos on Nudie’s walls, a somber oil painting of Old Lovesick occupies a prized space. Nudie sits down facing it and takes an ancient mandolin out of its case. Hank sits under his father’s lean face and takes the guitar someone offers him.

There’s mandolin talk and reminiscing as they tune up. Nudie starts to play an old hill ballad, “Ramona,” a haunting air with its Scotch-English roots still audible. Nudie plays his mandolin—two centuries old—with great tenderness and very little skill, and sketches the melody with a timeworn voice.

Next they drift into “Blue Dream,” another mountain lament; a dozen customers gather around. Nudie’s an old man recalling a woman and a river, recalling much that is gone, and the eyes of a matron across the room begin to fill with tears.

“Darling,” Nudie recites, “I can still feel your kiss on my lips … won’t you come back? Won’t you, just once? You won’t? Then FUCK YOU, YOU LOW-DOWN BITCH!”

The timing is George Burns/Julius Erving perfect, the jump from heartbreak to profanity made in one nimble move. Our laughter is sudden and uncontrolled: Nudie’s just placed the two crucial elements of country music, mourning and outrage, face to face.

Hank, who rarely wears anything more gaudy than Levi’s, is suddenly enchanted by a jumpsuit—skintight and spangled with purple butterflies—that Elvis Presley ordered just before his death. As Becky and Albert exchange helpless glances, he goes to try it on.

Having been packaged since infancy, he won’t be packaged again. He rejects the blind love that most singers court.

Alone with Nudie in a corner of the store, I ask him about Bocephus.

“I’ve known that boy all his life. He’s a helluva man, a helluva singer, and let me tell you something from the bottom of my heart—I seen him gettin’ laid when he was seven years old.”

(Later, when I read the quote to Hank, he roars and shakes his head. “Naw,” he smiles. “I was eight.”)

Hank comes back, decked out in butterflies. He buys the suit for $1,200—only, it seems, because of its connection to Elvis. (Five days later he decides he doesn’t really want it, and has it shipped back to Nudie.)

After visiting a few guitar shops, we return to Nudie’s for a photo session on the roof. Hank’s mood, dampened by flu and medication, has been slowly warming as we drive.

His size and manner and history conspire to make you forget his age. Until now, he’s shown no sign of being 28, but clowning on the roof, with the L.A. skyline behind him, he becomes a young man.

“Hello,” he intones, in a perfect imitation of Lorne Greene on Bonanza, “this is the Ponderosa, and these are my people … some of ’em are a little weird, but they’re all I’ve got. This here’s my horse Fag … ”

Once he gets started on Wild West shtick he reveals a little-boy side. He’s a passionate fan of Yosemite Sam, the Mel Blanc cartoon sheriff. He even got Blanc to record the message on his phone-answering device—“All raht, you ornery varmint, leave yer name ’n’ number or ah’ll plug ya fulla holes, ya big galoot!”

Hank’s sense of humor is a hybrid—sometimes it’s backwoods mock-dumb (“They’re gonna have another drought in L.A., ’cause all this rain’s washed the water away”), and sometimes it’s down-right black. (At one point at the Palomino, when his amplifier began to squeal, he said, “Sorry, I’m gettin’ some feedback from these wires in my head.”)

But the humor vanishes as quickly as it appears, as Hank stares down at Los Angeles.

“Gawd,” he sighs. “Sometimes it seems I’ve been on the road forever.”

It’s Saturday night at the honky-tonk, with all that that implies. A 300-pound behemoth in worsted picks a fight with a scrawny longhair, a tattoo artist covered with his own handiwork chats with a woman in leather, John (“Gentle on My Mind”) Hartford is called onstage to play a remarkable solo on his face.

“Git rowdy,” someone hoots, as someone always will. This is the Temperament Exchange: For the price of a draft you buy the rights to a stranger’s psychosis, or a night’s feigned intimacy … GIT ROWDY! IT’S SATURDAY NIGHT, GODDAMMIT!

Becky Williams, with her seraphic face and calm intelligence, is probably the least rowdy person in the place. She talks in a Louisiana accent thick as gumbo, with that lilting question mark at the end of each sentence.

“I first met Hank just a week before his fall. Next thing I knew he’d fallen off that mountain, and they told me he’d never look the same again. Only thing that worried me was that, with the plastic surgery, his face might not seem … real. But it did. And he seemed like the same person, too.”

In C&W circles, of course, the “good-hearted woman” is the traditional Rx for the blues. Becky Williams is certainly that, but she’s quite a bit more. She graduated from Louisiana State University with a major in music, and she’s one of the few people who can read serious novels in crowded motel rooms.

“I’m damn lucky to have that woman,” Hank says when she’s out of ear-shot. “She stood by me and never flinched a bit. Not only that, she’s a pretty good hunter. We can share things … I looked at her in the hospital one day, and I thought: If it’s this good through the bad times, think what the good times will be like. And let me tell you, they’ve been good.”

By now the Palomino crowd is screaming for him. Tonight there are fewer death-cultists in the audience, a few more true fans. It’s a war of attrition, but it’s slowly being won.

“Ladies and gentlemen, let’s hear it for the one and only BOCEPHUS … MR. HANK WILLIAMS JR.!”

”I woke up the next evenin’ in intensive care, and my jaws were wired shut. ’Course there were no teeth. I’m runnin’ my tongue around, feelin’ nothin’ but brass wires. Tubes down the throat, the whole bit. I rolled my eye around and looked around: Everything was so lily-white in the room, and I saw the mountains out the window covered with snow, and then I was out again.

“They said, ‘If he makes it eight days. he’ll live.’ But they didn’t expect me to. They figured my brain had to be infected, from me touchin’ it and the wind cuttin’ through it.

“And my head’s a basketball, all shaved too, with stitches and wires all over it. But I couldn’t see myself.

“Next morning I asked the nurse, ‘Is this my nose?’ And she said yes. I said, ‘Are you sure it’s not a plastic nose?’ And she said no. See, it was just flapped over there, like you took a flap of cloth and peeled it away, and they just hooked it back in there. So it was my nose.

“Then I started noticin’ the sounds—everything was too loud! The blips on the oscilloscope were like hammer blows! They were soothin’, for what they meant, but too loud.

“But now I’m gettin’ better, better, takin’ liquid through a straw, but the pain is gettin’ worse, so I’m takin’ a lot of Demerol, too.

“Then I caught myself callin’ for Demerol when I didn’t need it. Johnny Cash was in my room, and he’d been through his pill thing, and he said: ‘Hoss, don’t let me catch you buzzin’ for that Demerol when you don’t need it—’cause it’s real good, ain’t it?’ And I said, ‘Uh huh!’ But I remembered that, and I caught myself.

“On the eighth day they gave me a whirlpool bath, and that was the most fantastic sensation you can imagine. By now I could take little steps on my own, and I had to go to the bathroom, so they let me go myself.

“Well, they’d forgotten there was a mirror in that bathroom. I looked in that mirror and it was … bad. Much worse than I’d expected. Just this tremendous, swollen head, a monster’s head—one eye screwed way off to the side, like an involuntary thing, the other eye black, jaws wired together, no teeth—it’s got a grotesque look to it. There’s a hole in my forehead where the bone’s sunken in, and you can see the heartbeat pulsin’ in my forehead. Terrible green and blue colors, stitches down the middle of the face, unbelievable weight loss, bony limbs, ribs stickin’ through flesh. Muscles gone. That was a downer. I figured I’d get some Frankenstein roles. Or some leftover Jack Elam parts.

“That’s when I resolved myself that music was over. I thought, hell, there’s no way to get past this stuff! And I’d told God many times I didn’t want to sing, so this looked like the deal goin’ down that way. I went into a rejection period.

“Next day they brought a guitar down there, into the rehabilitation unit. I knew I could move my hands, but … it was a pretty quiet moment. Then I started, real slow at first, and soon I was rollin’ along! Then it almost turned into Request Time. Cash was there, and he’d sing a song and I’d tinkle along. And that was a rush.

“Better and better and better. So I asked ’em if I could hunt in October, which was two months later. They said, ‘No, you’ll be here at least six weeks.’ Fifteen days later I left.

“Dick’s wife, Betty, said, ‘You’ve been left here for some purpose.’ It seemed that way. Shuffled outta that hospital and up to Dick’s house. Stayed there for a month, readin’ every Indian book I could find. Bought a guitar and started playin’. Bought a big hat to cover the hole in my skull, sunglasses to cover my eyes. And blue jeans—Gawd, that felt good, to wear blue jeans!

“I’m still wired together. Couldn’t see too good, but I’d watch the Yosemite Sam cartoons at 3:30. Progressin’ along.

“Then I had to go back to Missoula to get the wires out. Doctor sat me down in a chair and said, ‘Hold on, this is gonna hurt a little bit.’ By now they’d given me so much pain killer they couldn’t give me any more, so it had to be done without it. And he said, ‘This wire is coming from just behind your eyeball,’ and he got hold of it and just yanked it clean out through my jaw. And it hurt, all right. ’Cause it was wire through bone.

“Then he took the other one out. Well, my jaws have been wired for a month. So when we got back to Dick’s house I had Betty make me up the most beautiful tuna fish sandwich. And I took this big bite, so excited to be eatin’ again—and there was nothin’ but a wet circle on the bread where I’d bitten. See, all the muscles were gone. Freaky. So I threw the damn sandwich and bounced it off the wall.

“Well, I could eat, but not that stuff. So Betty started makin’ spaghetti, casseroles, stuff like that. Man, I was really doin’ good then I eat a lot anyway, and I thought: This is great!

“Also, I could start to sing now. Plus I took my .45, to see if I could sight with one eye, and I hit the damn bull’s-eye first time. That really turned me on.

“Left Montana in October with my big Alabama hat pulled down low. Got home, started drivin’ the pickup, shootin’, feelin’ good. Then the doctor told me the jaw was healin’ wrong. Swung over to the left. This was two weeks after I’d started eatin’, and he said they’d have to wire the whole thing over.

“Now this was a bummer.

“Back to the hospital, back on the table, pop, pop, break the jaws again. Take a knife and cut the gum away. Bring it over there, line it up right, I’m wired up again. And they worked on the nose—the nose is headin’ east, lookin’ pretty bad. “Come back to Cullman, wired up. Went huntin’ that season, like they said I wouldn’t do, killed a deer. Go back to Nashville and they yank the wires out again. Nose is better, eyes a little better.

“Mother died right about then, and at the funeral I guess I looked a little weird. The papers said, ‘Williams looks like death himself.’ Big funeral—George Wallace came down, a bunch of other folks. All the black people linin’ the streets, and white people, heads bowed. It was a rough time.

“Then oral surgery, takin’ metal out of the roof of my mouth. Then we need a forehead plate to get the brain covered better, ’cause it’s just skin still, no bone. This was March. April we started playin’ shows again.

“Got this funny toupee on my head, along with the hat and glasses.

“Then we had to go to this eye doctor, get the orbit of this eye built up. We get it done, leave the hospital, the eye looks a little bit funny.

“We go down to Becky’s folks’ house for Thanksgiving. And we’re sittin’ around the table and everybody’s givin’ me some mighty strange looks. So I go into the bathroom—somethin’s come loose, and this whole implant has rotated up, and this eyeball is stickin’ out—it’s red, it’s blue, it’s terrible, it’s runnin’. Had to go back for another implant.

“See, all these operations—you’re lookin’ forward to each one. Each one’s a step. Each one moves you forward …”

The “den” is generally a dumb name for a room with a TV, recliner and Parcheesi set. Williams’ den, however, houses a grizzly, a timber wolf, an owl and a bobcat—all stuffed, of course, but so artfully that they seem to be sizing each other up.

We’re sitting in the midst of this silent animal face-off, drinking Jack Daniel’s and watching the news. But Wallenda’s death has spooked Hank a little, and he’s itchy to move downstairs, to the shop where he works on his guns.

Guns have been a lifelong passion for him. He owns several hundred, including many rare models, and he is an expert hunter and gunsmith.

Today he’s retooling the grip on Becky’s .45, adjusting the trigger alignment, doing it all by feel. As I watch him work, his 6’1” frame bent over a table, he looks like a medieval craftsman.

When he’s finished with Becky’s gun, he suddenly decides it’s time I fired some “real weapons.” He ponders the choices, then reaches behind a loose ceiling panel for a long khaki bag. Slipping on a pair of ear protectors, he motions for me to follow him outside.

The Alabama woods are quiet in the twilight, but you can see firing lanes set among the trees—rows of stumps honeycombed by shots, spent cartridges, massacred tin cans. As we stand before the widest lane, Hank unzips the khaki bag and takes out… a machine gun.

“Listen, Hank—is a machine gun a good thing to start on?”

“Gawd, yes. It’s like in the movies.”

And he’s right. It’s crazy—the trigger senses every vague impulse to fire, and you’re barely conscious of your finger’s intervention. I’m wounding the cans and stumps at random, amazed by the ease of it all.

“Now hold ’er sideways and spray it,” he says, and, as in the movies, it happens. The weapon trembles as bullets dig a trench in dry earth.

“Kind of a rush ain’t it?” Hank grins.

It’s a rush all right. Machine guns are hooked so well into the subconscious—you could wipe out a whole family as an afterthought.

But that’s a city kid’s rush. There’s no homicidal edge to Hank’s love of guns; he doesn’t have enough hatred for that.

Hank Williams Sr. was known, in freaky moments, to ventilate motel rooms with gunfire; but just as Hank Jr.’s learned to control his melancholy better than his father did, he’s also more circumspect about when and where he shoots. And he always keeps the first chamber unloaded, just in case.

After shooting, we stroll around to see his dogs and smell the spring air at dusk. Tennessee is the last green hill on the horizon. Silence grows around the house in abundance, like a crop, as darkness falls.

When it’s time to leave, he offers the use of his pickup truck and a bottle of Jack Daniel’s—we’re in a dry county. Driving through nighttime Alabama that way, I feel, surprisingly, half at home.

Hank Williams is often called the “father of modern Nashville”: It’s true economically as well as spiritually. Although his own style was relentlessly down-home, he was the first country songwriter to have his work “covered” by many pop artists. Tony Bennett, Polly Bergen and Andy Williams all scored early successes with saccharine versions of Hank Williams songs, and the blend—earthy sentiment and windy string arrangements—made Nashville rich.

So when Hank Jr. finally left Nashville in 1975, he was leaving the house of his father, perhaps for the first time.

Now the plates on Hank’s beige Fleetwood read Alabama Governor’s Staff—he’s an honorary deputy of the state, a post he takes fairly seriously. Considering he also extols dope-smoking and drinking in a dry county, an observer from the North sees a paradox.

It won’t be resolved. Hank has no discernible politics beyond a love for his birthplace and an allegiance to his pleasures. He loves black music—but what musician doesn’t? The closest thing to political awareness in Hank is a populist streak that you can also find in characters as disparate as George Wallace and Thomas Paine.

On my last day in Alabama, Hank visits the dentist. One of his false teeth is too sharp and must be filed down. When he’s finished in the chair, the dentist comes out into the foyer with him, beaming.

“It’s on the house,” he says, clapping Hank on the back.

“Hey,” says Hank, unsmiling, “I’ll tell all my friends to come up here. Free dentistry.”

“Just for you,” the dentist laughs nervously.

Outside, Hank is fuming. “On the house … Gawd, next thing some poor bastard’ll walk in there in agony and he’ll charge him $35 just to look. Gawd, I hate that shit.”

For politics, that will have to do.

Williams’ home is 140 miles south of Montgomery, where his father lies buried. A ritual visit to Hank Sr.’s grave is the C&W equivalent of communing with Keats at his graveside in Rome—hundreds of songs have been written about it. Hank Jr. sings the best of them, “Montgomery in the Rain,” written by Steve Young. “I’m gonna go out to Hank’s tombstone, and cry up a thunderstorm chain … ”

Hank adds a chilling line at the end of Young’s song: “You all know me well by the songs on the cemetery wind … ” And he pronounces it “winnnnnd,” so it whistles through the room. When he sings it, you’re not sure if you’re hearing a voice from the grave, from a living son, or from some ghastly fusion of the two.

“The pure products of America go crazy,” said William Carlos Williams. If that’s true, we might be grateful that nothing is pure anymore. Hank Williams’ voice mapped out an America of unyielding farms and open skies, bad luck and long railroad trains; and his son was supposed to live in it. But it was a smaller America, without Motown bass lines and Eric Clapton guitar licks, and to keep a child/man there was to freeze him in time. So Hank Jr.’s story has been a long catching-up, a fight to be his own contemporary.

It’s been a story rife with purity and craziness. Pain alternates with gross comedy—at his mother’s funeral, Bob Harrington, the “Bourbon Street Preacher,” stood over the open coffin singing “Hey, Good Lookin’ ” to the deceased. Blood ties loosened and tightened—a Southern gothic sense of predetermination—and at the center, one human, who somewhere found the sanity to say, “I don’t want to be a legend, I just want to be a man … ”

As a kid, he was subject to a terrifying force: indiscriminate love. Sometimes he’d try desperately to alienate a crowd, only to find they still “loved” him. Loved his chromosomes. Loved the fact that his father died young.

As a man, then, he seeks respect for what he does. This has seriously hurt his career. These days, he plays far too many junior-high gyms and roadhouses, when with a little honing of his act and a change in focus he could be packing showcase rooms in New York and L.A. Sales of his latest album, The New South, have been somewhat disappointing; as the country proverb has it, he’s hiding in plain sight.

It’s frustrating, of course, for those who admire him, but at base he just doesn’t care that much. Having been packaged since infancy, he won’t be packaged again. So he indulges himself, sloughing off the demands of the commercial world. He rejects the blind love that most singers court.

But he knows what he loves: music, Becky, food, guns, solitude, pickup trucks. When asked what got him through the fall and the months of recuperation, he said: “I had just learned how to relax, to enjoy life. And I thought: I want more of this.”