He goes to work at nine-thirty Saturday morning of the Memorial Day weekend. He leaves the elevator and walks into the lobby of his apartment house. The young doorman says, “Morning, sir.”

“Yeah. How you doin’?”

The doorman counters his scowl with a grin, and shrugs. “Awful.”

He likes this, and smiles, the first of the day. As someone once said, every day is the worst day of Jimmy Breslin’s life.

As he walks north up Central Park West, it is hot, jungle humid, the kind of day that is a prophesy of New York in high summer. The sky is white and gray and black, the smoldering colors of a dump fire. It starts to rain softly and Breslin looks up, furious. The writer as Ahab, ready to strike the sky if it insults him.

As he nears 72nd Street, his New York ears catch a sound, his New York feet feel something in the sidewalk—the uptown train pulling into the station below him. Breslin curses. Even if he were a track star he couldn’t catch it. On Saturday mornings you can wait half an hour between subways. He’s out in the street, hails a cab, settles back and lights a cigar of truly gangster proportions.

“I am one,” he has written in his column, “of a half dozen or so in New York who is over the age of fourteen and does not drive a car. It is just another part of a life of noisy desperation.” Now, when he’s in the cab, it’s like a child’s first trip. He watches everything passing through his cigar smoke as the cab rattles and rolls uptown.

Yesterday, at the racketeering trial of former Secretary of Labor Raymond Donovan and seven others, a woman juror, Milagros Arroyo, had caused a sensation. The jury had been deliberating a verdict for five and a half hours when something in Arroyo came loose. She locked herself in a bathroom and demanded to see a priest. The judge put her in the witness chair, questioned her, and Arroyo responded by quoting the opening lines of the Twenty-third Psalm. After nearly nine months of trial the courtroom was in an uproar, and the attorneys were demanding a mistrial, refusing to accept an alternate juror. The judge would hear motions today in court, and Breslin would have a story.

On the Madison Avenue Bridge he looks across the river toward the South Bronx and his destination, a huge square pile of a building, something Mussolini would have liked, an example of the architectural School of Brutalism, perfect for the Bronx County courthouse. While he’s waiting for a light, a nearly destroyed Pinto pulls up. The young black man at the wheel looks over and says, “Jimmy Breslin. Hey, Jimmy Breslin, right?”

“Yeah. Where you goin’?”

“Work. Down in Manhattan. Hey, great story on the polar bear kid.”

The second smile of the day. “You’re right. It was a great story.”

The polar bear kid. Earlier in the week, on a warm night, Juan Perez, 11, had sneaked into the polar bear cage at the Prospect Park Zoo and was mauled to death. Breslin’s column was from the neighborhood where the boy had lived, with an interview of an upstairs neighbor. The column was about a brave, mischievous boy living in a home without a father in a poverty-blighted Brooklyn neighborhood, “a neighborhood of old apartment houses that are packed with people who trace their beginnings from anywhere south of Virginia to the islands in the last waters of the Caribbean.” At 11, Juan was just beginning to run the streets, just beginning to be beyond his mother’s control. Breslin wrote, “This was a most startling news story … But at the same time, perhaps somebody should stop just for a paragraph here this morning and mention the fact that there are many children being eaten alive by this bear of a city, New York in the 1980s.”

The first floor of the courthouse is dim, empty, and Breslin hurries to share an elevator with one of the defendants in the Donovan case, state Senator Joseph Galiber, a tall, distinguished black man, 62 years old, looking as if he hasn’t slept in days. “How you doin’?” Breslin asks.

The senator shrugs. “Where you goin’ this weekend?” A strange question, a tool of the successful journalist, throwing in something offbeat, innocuous, and Galiber is almost ready to respond but is clever enough finally to just smile and shake his head.

Down a corridor, there is a wild sound buzzing off the marble walls. Turning a corner, the senator is caught in mid-stride by a blizzard of TV lights. Next to the courtroom door, behind wooden police barricades, are camera crews and photographers, at least a hundred people.

Breslin heads down another corridor and finds John Nicholas Iannuzzi, attorney for another of the defendants, William Pellegrino Masselli, a.k.a. Billy the Butcher. Iannuzzi does everything but grab Breslin by the lapels, making a point. He has on what looks like a polo shirt and a red tie wide enough to have been fashionable a decade ago. “Jimmy,” he says, “I’ve never seen anything like it. Draggin’ the poor woman around, throwin’ her in the witness chair like she’s a sack of potatoes. She’s sayin’, ‘The Lord is my shepherd, the Lord is my shepherd.’ Apeshit. The poor woman is goin’ fuckin’ apeshit.” Breslin listens as if he were getting a report from a subordinate officer, looking over his shoulder, at his feet, only rarely looking directly at the attorney.

Inside the courtroom he moves around, talking to people whom other reporters, busy speaking to one another, are ignoring. One person who has information is a midget in a perfectly tailored suit. Another is a man in a once-white guayaberra, a blue smudge of a tattoo on his forearm, and a ventilated baseball cap with admiral’s scrambled eggs on the brim. Breslin is making notes on folded yellow legal sheets.

The judge arrives and court begins. Breslin sits slumped in the last row. Six of the eight defendants want a mistrial. Donovan’s lawyer quietly says his client will accept an alternate juror. Iannuzzi shouts that “this is the sorriest spectacle I’ve ever witnessed.” And, “I want my juror! I want my jury! I want a hearing! I protest! J’ accuse!”

Poor Billy is living proof that The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight, a Breslin title that has entered the language, was not wild satire or imaginative comedy, but dead-on realism.

The judge calls a recess, and Breslin immediately goes to Billy the Butcher and walks out with him. Hysterics from the camera crews, falling over one another in the blast furnace of TV lights. Billy goes to the elevators and is cornered by the lights. A woman reporter with a microphone as long as a baseball bat begins to question him. She stands on the other side of the lights, four feet away. Billy says, “All double-talk legalese,” and walks away, down a long corridor. No one follows him except Breslin. They both lean against a dirty marble wall in the sudden quiet. “So what do you think?”

“Jimmy, it’s got nothin’ to do with me.”

“Come on.”

“I’m just spice for their stew here.”

“Donovan’s going with the alternate.”

“Good luck to him.”

“You’re taking the mistrial?”

“Yeah. Donovan’s not gambling. He’s a3-1 shot.”

“You sure?”

“Absolute. He’s 3-1 and should be more.”

“Then why don’t you go with the alternate?”

“If Donovan wins, they’ll never retry me. I f he loses, then Donovan appeals. That takes years. They can’t retry me until the appeal is over. “I’ll be fuckin’ dead by then. There’s no way I can lose.”

At 60, Billy the Butcher is not doing well. His health is shot. His son was murdered a few years ago, and he has a murder trial of his own coming up after this one is through. Breslin asks him where he’s done time. “Dannemora. Worst joint in the country. Fuckin’ iceberg up there. Tallahassee. Another bad place.”

Breslin says, “What about Tony’s [Salerno] trial downtown?”

“I never met him in my life.”

“Bullshit.”

“I take an oath on my dead kid, I never met the man.”

“You know him from the streets.”

“Nah. I’m from Morris Avenue. Tony’s from Harlem.”

Billy starts talking about his health. “I don’t know, I went to the hospital, they say my stomach’s all right, no cancer there. No cancer in my body.” He pauses. “Nothin’ in my brain.”

Poor Billy is living proof that The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight, a Breslin title that has entered the language, was not wild satire or imaginative comedy, but dead-on realism.

Breslin’s late and running. Outside the courthouse he stops for more cigars at a smoke shop blaring salsa, then is out on the street hailing a taxi. A gypsy cab with a furry red interior, four pine-tree air fresheners making the cab smell like the cabinet under your sink, and a Nigerian driver. “Forty-second and Second. The Daily News building.”

At a light the driver is giving directions to two guys looking for an auto-parts store on Jerome Avenue. The light blinks green, goes to red, back to green. “Come on, come on,” Breslin says. “I’m late.”

The last two words should be said to cabbies only by true sportsmen. All the way down Second Avenue, the Nigerian is running lights, lane-jumping furiously, leaning on his horn, cranking up his tape deck of African music made up of booming drums, chants and what sounds like tin cans being beaten with sticks.

Between Second and Third, Breslin gets two cups of coffee from a coffee shop and crosses the street to the Daily News building. The security guard says, “Excuse me, sir,” and Breslin, still walking, says, “I’m goin’ to work.”

On the seventh floor he enters his corner office looking out on 42nd Street. There are boxes and wastepaper baskets, an old Olympia typewriter, papers everywhere, a bookcase, half-filled, the books upside down, on their sides, as if they’ve been thrown from across the room. He sits at the word processor, spreads his notes out, opens one coffee, lights a cigar and types his lead: The setting was for a crap game. In a few minutes he’s lost in the story, cigar and coffee forgotten, using a rapid hunt-and-peck style, as if he wants to put his index fingers through the keyboard.

Nearing deadline, he answers his phone, shouts, “In a few minutes,” and slams down the phone. Every sentence, except the lead, is rewritten at least once. Two hours later he’s done, but still fiddling with the piece, reading off the screen, working on a sentence: In the morning, the difference between throwing dice against a garage wall on Southern Blvd. and the game scheduled to go on in the courtroom was that there were only supposed to be two players. His wife calls to remind him that ninety people are coming to the apartment in two hours for a wedding.

Down the hall, in the abandoned city room, he looks over the shoulder of the editor as the story comes up. If he wants, he can stop back later to make changes when word comes from the Bronx about the judge’s ruling.

Exhausted, he’s got to have a walk, or maybe a swim, to come down. Since six-thirty this morning, lying in bed with a telephone, three newspapers and a thermos of coffee, Breslin, 58, has been working. It’s now three o’clock and he’s still not satisfied. He finally won the Pulitzer last year, but it’s been like this for almost twenty-five years, three columns a week, writing the central stories of his city, which are, in no particular order, the amazing thievery of the powers-that-be, the forgotten and despised poor and the fast, fierce humor of New York neighborhoods. Week after week, the life of noisy desperation.

Three times a week, writing in what he calls “street Irish— with descriptive talent.” For the price of a newspaper you can get a description of the steps of City Hall: “with grooves worn in them from seventy-five years of people running up them and trying to leap through the doors and make a huge splash in the gravy.” Or a description of Sunday in certain Queens neighborhoods as “the day belonging to the Lord in the morning and the children in the afternoon.”

Breslin is one of only a few writers who have kept the faith, who have not turned cynical but are still outraged at what is happening to the poor of the city. He almost never uses statistics when writing about issues, but rather writes about the people the statistics obscure, He is one who disdains the overview, the big picture. What he is saying is that New York City is getting worse day by day for all of us, and of course much worse for those who have so much less. Unless there is a change, Breslin says, and not some hack politician’s windy words o f change, New York City is certain to be more grim, more violent, more at odds with itself.

“Jimmy Breslin hasn’t told the truth for years—not even to his diary.”

But then there’s the humor, the chronicling of his “daily incompetents.” Fat Thomas, the bookmaker—cab dispatcher at the Four Ones in Ridgewood. Queens, who lives by the creed “Only God behaves.” When Thomas hit it big with a phenomenal run one football season, he decided to look for investments. A friend in real estate knew about some property. Fat Thomas asked, “Is real estate as much fun as hookers?”

Or how about Un Occhio (One Eye), boss of all bodies, running his shadowy underworld out of a candy store on Pleasant Avenue in East Harlem? Near the store is a marble triplex, a palace whose façade is a crumbling tenement. There, Un Occhio lives with his wife, Meenel, “who is seen only at funerals of men who have had particularly violent deaths.” The capo di tutu i capi himself prefers poison to settle differences of opinion because of its simple beauty. “ You give them food and they die.”

Hilarious stuff, and funnier still when the Arizona State Police wrote to Breslin for information and the FBI and the Organized Crime Task Force in New York spent a month in East Harlem looking for the fictional Mafia chieftain. Recently, he wrote a piece about how real-life godfather John Gotti had received $624,000 from the Iran arms-sales diversion. Breslin received calls from investigative reporters from as far away as Australia. Daily incompetents come in suits and ties as well as blue collars.

Two weeks before Billy the Butcher was rolling bones in the Bronx, I was home in Queens, the place Breslin has described as “the Athens of America,” not for the huge Greek population in Astoria but more for the sterling qualities of democracy and gentle political debate that define the borough. Home in Queens, a place Breslin has excavated as deeply as Faulkner mined Yoknapatawpha—particularly in last year’s Table Money, his best-selling, critically acclaimed novel of the working Irish of the borough.

My project for the day was watching the Iran-contra hearings and attempting to figure out just what it was Bud McFarlane was saying. No easy task. As McFarlane began yet another of his drifting little speeches in the voice of a shipwrecked sailor recalling the disaster, I received a dinner invitation. It was Ronnie Eldridge, Breslin’s wife, speaking in her quick, musical voice, speaking English asopposed to the 2001 computer-speak of Bud. “Look, why don’t you come at seven-thirty. We’re eating non-seasoned food. It’s horrible. But you’re welcome.”

The poet of Queens Boulevard now lives on Central Park West in a spacious apartment. He lives there with his wife and various young people. When I asked where the bathroom was. Ronnie told me. “In here, off this room. Careful, there’s some kid camping out in there.”

She had greeted me at the door, a pretty woman with that delightful voice.

Behind me came Helene, an elderly woman recently widowed. “ I’m here a lot,” she said. “There’s always something going on.”

“Jimmy,” Ronnie called. “Jimmy. He’s here. J.B.!” Then to me, “Come on in and sit down.” She gave me a drink and talked about the apartment and the family. She had been a widow with three children and Breslin a widower with six children when they married. Not only was the number of people chaotic, but a Queens Irish-Catholic crowd thrown in with a West Side Jewish family was not easy. Her children had been upset when Breslin used them and their conflicts with the Breslins as material for his column. “It’s settled down now,” she said as Breslin entered the room so fast he looked as if he were race-walking. He came at me, dressed in dark slacks, a blue dress shirt with the French cuffs flapping like loose sails, barefoot. He took my hand and then moved off to the side, a good jab, stick and move. “You all right?” he said, looking at the glass in my hand, and then was off. Ten seconds, tops.

Ronnie went to prepare dinner and Helene offered to help. “Did I tell you it’s non-seasoned food? We’re trying to lose weight. He’s angling for a new TV show and TV makes you look enormous as it is.” (Jimmy Breslin’s People ran for thirteen weeks in 1986 to good reviews but low ratings due to the fact that only farmers and astronauts were awake to see it. When Breslin read rumors in the papers that ABC was about to cancel the show, he took out an ad the next day to announce he was canceling ABC.)

When the women left, Breslin came in again, rubbing his bushy John L. Lewis eyebrows, moaning, the worst day of his life. He sat on the floor, leaning against the couch. He wasn’t drinking these days, he told me, looking at his toes.

“If you care about what you do. It’s all hard. It’s day labor.”

He looked at me as if I were an imbecile. “Fuckin’ right I miss it. And the bars. It was my only sport.’’

I asked him if it was true that once, after a particularly long and wet night, he had felt so catatonic in the morning that he had called an ambulance to cart him to the office.

“Yeah,” he said, smiling. “True. Oh, it was beautiful. Sirens. lights. But what’s important is that I got to work.”

He’d been working hard lately, not only on the column: he’d just finished a TV movie for CBS about New York cops, a theater in Louisville had commissioned a play, and he’d finished a novel, He Got Hungry and Forgot His Manners, set in Howard Beach and due out early next year. It’s the story of an Irish priest who, after long service in Africa, is transferred to a parish in Queens, where he arrives with his companion, a seven-foot cannibal.

But most important. he had just announced he was leaving the Daily News, his base for eleven years, to write his column for arch-rival New York Newsday beginning in October 1988.

“Why?’

Again the look that categorized me as a poor soul. “For money. They offered me a lot of money.’’

“How much?’’

“Big. Huge.”

“How much?’’

“It’s a five-year deal starting off well over $400,000 for the first year and escalating every year after that [up to $1 million for the last year]. You can print it. It’s good for kids in this city to know you can make big money as a writer and not just as a basketball player.”

“How different is writing plays, movies and novels from the column?”

“It’s the same. If you care about what you do. It’s all hard. It’s day labor.”

Dinner was not horrible, but delicious. Scallops, red and green and yellow peppers and green fettuccine. Breslin poured the wine for those drinking, filling the glasses to the brim. The phone rang every minute and a half. Breslin leaned on the table on one arm, slumped in his chair. Remove the arm and he’d disappear under the table. Halfway through the meal his sister, Deirdre, a teacher at Fordham, arrived. The conversation was about politics—local, statewide, national. Helene asked, “Did you see that man on TV today?’’

“McFarlane?’’ Deirdre asked.

“Yes. He looked to me like he was drugged.”

“Yeah,” Breslin said, getting up to answer the phone. “And I think he’s a stew bum along with it. You see him goin’ for the water every minute?”

Breslin’s son Christopher arrived in shorts and a T-shirt, sweaty from a game of basketball after work. He’s a student at Boston College, home for the summer, working as a research intern in the record business. Breslin questioned him thoroughly about his day as Christopher made short work of the scallops and pasta. “He’ll support you in your old age,” I said.

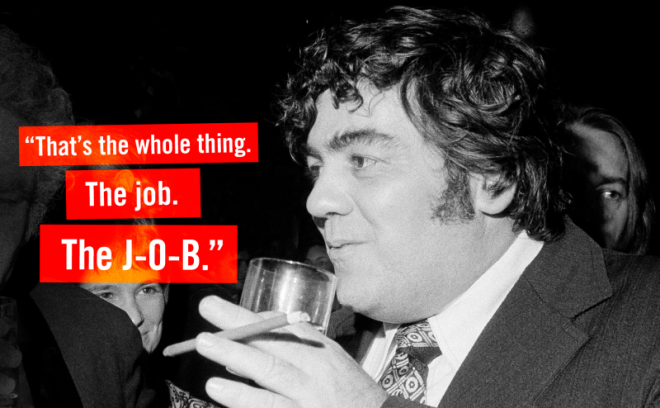

“Nah. I’m just concerned that he work. That’s the whole thing. The job. The J-0-B.”

Another day with Breslin—the morning the column about the polar bear kid appeared. When Breslin opened the door, he was again rubbing his eyebrows, his face in mourning. “I’m punched out. Totally.’’

“Great stuff today.”

“Yeah. that’s what did it to me. Tough story to do. Took a lot out of me. The poor kid. Then I’m up half the night,” he said as I followed him into the kitchen, “goin’ through phone books to see if I spelled all the names right.”

He was splendid in pale-blue pajamas, one gangster cigar in the breast pocket. I sat at the counter in the kitchen on a high stool. Across the room the Iran-contra hearings were on a portable TV, an elderly woman proudly testifying about buying trucks and weapons for the rebels.

“Look at this one,” he said, his face lighting up. “She’d be perfect for the Goetz jury.” When Bernhard Goetz opened up in the subway and shot four black men, Breslin was the first and, for a while, the only voice that questioned the vigilante tactics. While white New York cheered the subway gunman, Breslin was saying, Calm down, look at it squarely, look at the issue of race, look at yourselves and your delight that one kid is paralyzed for life. He quoted George Will, who, in his column, loftily examining the Goetz incident, wrote, “Let us now praise anger, and especially anger in the form of a desire for justifiable vengeance….If you do not take Shakespeare’s word for it, then take Clint Eastwood’s—or else.” Breslin’s response was: “I got a picture of this little blond man, Will, sitting deep in a movie seat and touching himself as Clint Eastwood pulls out his gun.”

“There are only three prizes anyone knows about—the Academy Awards, the Nobel and the Pulitzer. Now, whether they’re all rigged, which I think they are, they still are the prizes.”

The talk turned to drugs in the poor neighborhoods. Breslin worked an espresso machine (“It’s decaf. If I drink the real thing, my heart goes like a trip-hammer.”) with the elan of any headwaiter in a neighborhood Italian restaurant. “See,” he said, deftly changing filters, “the reason everyone’s pissed off about crack is that the blacks are running their own crime. The Italians, the Jews, the Irish, all had the right to pursue their own crime.” He sets a cup in front of me, sits down with his feet on the counter. “But when the blacks do it—look out. You know about the cops in the Brooklyn precinct shakin’ down dealers, breaking into places to steal? Amazing. Unbelievable. The cops never had to break in and steal from criminals. They were always paid off. Once the blacks realize that, you’ll never hear about crack again.”

Just as paper has never refused ink. Breslin has never been hesitant about voicing opinions. Here are a few of his recent thunderings:

On the Pulitzer Prize: “There are only three prizes anyone knows about—the Academy Awards, the Nobel and the Pulitzer. Now, whether they’re all rigged, which I think they are, they still are the prizes. And I got one. They gave me a thousand bucks, I gave that to my daughter, and that was the fuckin’ end of that.”

On Mayor Koch: “A bald man who substitutes comedy for government.”

On the Irish in America: “Sad. They forgot completely where they came from. Like everything they went through never happened.”

On Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan: “He’s so pompous that he ought to be a doorman for Buckingham Palace.”

On the English: “The foulest race on the face of the earth.”

On President Reagan: “A senile old fool.”

On New York Times book reviewer Christopher Lehmann-Haupt: “Every time you let a German near a typewriter to do anything except repair it, he goes straight to authoritarianism.”

On the possibility of ever working at the Times: “Jesus, that would really be giving up. That’s an insurance-agency job.”

We talked about his childhood, and were interrupted ten times by two phones on the kitchen wall. Every time one rang, he would groan. “Yeah? Oh, for—will you give me a fuckin’ break?” The phone was slammed down. “I’m goin’ nuts.”

When he was 6 years old, his father, a piano player and an alcoholic, abandoned the family. His mother went to work as a substitute high-school English teacher and then as a full-time worker for the Department of Welfare.

This made me think of the column about Juan Perez, the polar bear kid. Breslin ended it with a description of the funeral of the boy’s father. The father had died of drink, and the boy told a neighbor about the funeral. “I saw my father. His face was swollen. But I wasn’t afraid. I looked at my father. I wasn’t afraid.”

And as Breslin spoke about his mother, I remembered something he had said the other night about a solution to the poverty of New York. “The only political word I ever knew was ‘jobs.’ If you don’t have at least one person in a home getting up and going to work, you’re finished. Get jobs for people, good work for them, and they’ll get education and better housing. And I’ll tell you, getting back to the race issue, if you had as high a number of white kids unemployed in this city as you do black kids, you’d have jobs in a minute.”

The phone again. It was his lawyer. After twenty-five years Breslin’s sacking his literary agent, Sterling Lord.

“I’m firing him,” he said, taking out a platter of turkey and going to work on a leg, using it as a pointer between bites, “because here I am. I win the Pulitzer Prize. I have a best-selling novel. I’ve got a critically acclaimed TV show, and what happens? Nothin’. Zero. It’s like a team wins 108 ball games and doesn’t make it to the World Series. I got a year here I can retire on, but I don’t get any help.”

There were loud women’s voices in the living room. “Oh, for God’s sake.” He got up and moved toward the door. “Goddamn kids.’’

Ronnie stopped him. “Now, calm down. Don’t shout at her. Please?”

“Yeah. Right.”

He came back with Kelly, his 22-year-old daughter, and made a call. “Yeah, I got your name from Jerry Della Femina. He says you’re the man.” Kelly, blonde, pretty, is pacing the kitchen, not looking at her father. “Now, look, she’s a great actress. Well, she’s an actress. She’ll do anything. She has the distinction of being the only student in the history of the High School of Performing Arts to cut school. Yeah, I’ll put her on.”

Kelly took the phone into the next room. A few minutes later, she was back. “So?” Breslin asked.

“Thanks.”

“Okay. So what is it, Kelly?”

“The J-0-B.”

“Right.”

A few hours after he finishes the Billy the Butcher column, Breslin’s apartment is packed for the wedding of Pete Hamill and Fukiko Aoki. Celebrities are bumping into one another as literary New York meets political New York. Broadway says hello to prizefighters. And newspaper people, along with a few Hamills, are dug in near the champagne bar. Michael Daly, former columnist for the Daily News, is describing Breslin, with affection as “a beast. The man’s a beast.”

Chamber music drifts down a hall where people hold drinks and pick from trays of hors d’oeuvres passed by waiters and waitresses in tuxedos. The bride’s mother is in a kimono, while the groom’s mother seems a bit stunned by it all. Peter Maas is talking to a reporter about East Hampton in the summer and the IRA, making sense of neither. Jonathan Schwartz leaves early: so does Pete’s brother, Denis Hamill, a columnist for New York Newsday. A gossip column reports the next day about a shouting match between Breslin and Denis at the party. There’s a quote from Denis saying, “Jimmy Breslin hasn’t told the truth for years—not even to his diary.” But, after all, it is the New York Post, so who knows whose leg is being pulled.

It’s a good party, and nobody seems to be getting seriously hurt. Seeing the guests, you realize that Breslin probably knows New York City better than anyone. He has working knowledge of agents and publishers, advertising people, actors, television executives, the mob, and he has roots in the white working class and a commitment to the angry poor of Brooklyn and the Bronx.

He speaks with his lawyer, Paul O’Dwyer; Bob Fosse: and Cork Smith, his editor at Ticknor & Fields. Jose Torres stops by to say hello. But then, suddenly, in the middle of the party, Breslin’s gone.

Down to The Daily News to work on the column, to make changes for the later editions.

[Featured Image: Sam Woolley/GMG]