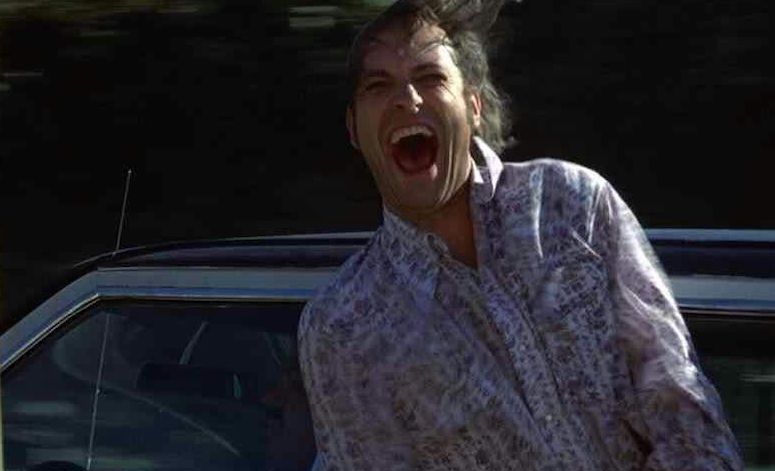

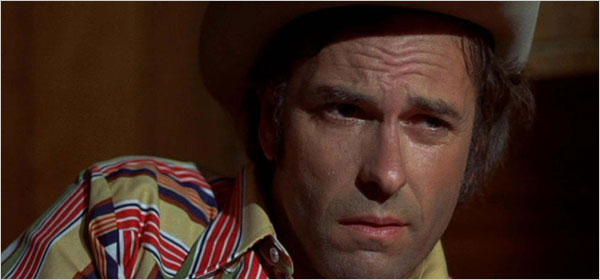

Maury Dann, the country singer, is sitting in a restaurant with his entourage. It’s one of those cheap little Formica-table places in Alabama, the kind of hard-light joint that says “All You Can Eat” outside. Maury is a hardscrabble guy, an ass-kicker, not quite a star, but still hanging in there. Right now he’s into his third day of booze and uppers and downers, and his hair looks like undrained bacon and his mouth is curled in a speed snarl, and he’s just trying to get a little of the road dirt off, along with his chauffeur and his slick-assed agent, a guy dressed in two hundred percent polyester.

But Maury’s little interlude is broken by a wailing drunken businessman who is claiming Maury screwed his girlfriend (which he did). Maury is trying to cool the man out, but the man is pointing at him, shaking a beer gut. He’s not going to let it go, and soon Maury is out of his chair, and the two of them are out back in the gray light, and the dude is pulling a knife on Maury, which is his last mistake. Because Maury Dann always finishes things that other guys start. He takes the man’s hand, bends it straight back into his stomach, and jabs the knife into his gut.

The whole time he’s doing it—killing another man—Maury is staring at him with these mean little ferret eyes, his jaw set in this terrible sharklike frieze. He’s tired of all the bullshit, of all the lame record jocks he’s had to suck up to, of his moronic groupies, exhausted from his own boozed-out, wasted days and lonely nights, half-crazed from all the shuck and jive. And it all comes out here in one murderous rage.

Not long after this scene, the lights come on at the AFI Theater in Washington, D.C.’s Kennedy Center, and the bearded, tweedy, professorial, student-film buff crowd applaud as Maury Dann himself sits in front of a mike and fields questions at a retrospective of his films.

For Rip Torn’s life has been one of constant struggle, a series of near misses, legendary battles with producers and directors.

There’s something surrealistic, Kafkaesque, about this whole scene, for Maury Dann is none other than actor Rip Torn, perhaps Hollywood’s most famous bad boy.

The mere idea of a Rip Torn retrospective is a trifle bizarre. Like a lot of people familiar with Rip’s strange career, I’m surprised that there are enough pictures to put on the screen. For Rip Torn’s life has been one of constant struggle, a series of near misses, legendary battles with producers and directors. He was known, in the sixties, as the “radical actor from the East,” and after a fast start in films, worked sporadically for the next sixteen years.

Then, suddenly, all of this changed. In the past few years he has become one of the most sought-after actors in America. He was nominated for an Academy Award for his supporting role in Cross Creek (but ironically lost to Jack Nicholson, the man who ended up with the plum supporting role in Easy Rider, a role originally written for Rip); he was in Don Siegel’s aptly named Jinxed, where he out-acted everyone else in the picture even though for two-thirds of it he played a corpse; he recently appeared with Reynolds and Eastwood in City Heat; and played in Songwriter with Willie Nelson. On television he co-starred with Loretta Swit in The Execution, played the district attorney in The Atlanta Child Murders, and received raves for his interpretation of Big Daddy in Showtime’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.

It seems that Rip Torn’s time has come round at last; all the years of being an outcast, of being considered “unmanageable,” “too wild,” “a radical,” are over. Here he sits, a real American outlaw artist, on the stage of the AFI Theater smiling and answering questions from respectful, loving fans. And yet, he is not really secure quite yet. He carries the scars of his battles with The System even now.

The first thing I noticed when we met was his powerful physical presence. Not powerful like, say, a Charles Bronson, but powerful like a working man, a guy who used his hands in real life. He was a rough-looking dude, a little thick around the waist, with big strong hands and wrists, and knuckles that looked like they’d been busted a couple of times—the kind of guy who worked in heavy construction, or maybe hung around the lube racks. He was about five ten, wore nondescript black pants, an old sweater. His shirt hung out in the back, and in his hand was a copy of the New York Times. There was absolutely zero Hollywood glitter.

The slitty eyes I’d remembered from his earlier roles were sagging a bit more now, and the wide, tight mouth was a bit more jowly, but he looked menacing all the same.

Still, the kind of kinetic weirdness that usually came through in his performances, the charged, active quality of stoned-out madness, wasn’t apparent. Instead, there was a shy quality, quick glances over at me, then looking away. A smile that disappeared when I smiled back.

“Look, there’s one thing I want you to say in this article. Tell people I didn’t walk off Easy Rider. It’s the truth.”

I assured him I wasn’t out to do him in. I congratulated him on his recent spate of films, and he shook his head. “Look,” he said, “you know, maybe I’d rather direct, because, what the hell, you don’t have to sit around and wait for the phone to ring.”

“Yeah,” I said, “but lately you haven’t had to wait much. It must feel good.”

“Sure,” he said, “but you never know. Just last week on Beer, the new movie I’m in, things got weird.”

“How so?” I said.

“I was in makeup one morning, and a guy came in, said that Bob wanted to see me. That’s Bob Chartoff, the producer. Right before makeup. Man, it got real quiet in there, and I said, ‘Why’!’ The guy said, ‘He’ll tell you in his office.’ ” Rip looked up at me, nodded his head, and scratched the back of his neck. His muscles seemed to tense up just telling this tale. “Anyway, I said, ‘First, I’m going to my trailer to get my coat, I feel a chill coming on.’”

Rip had slumped forward on the barstool, and suddenly looked much older than his fifty-four years. “But in the end, it wasn’t me. They were letting Sandra Bernhard go. When they told her, Sandra cried and I started crying right along with her, and I held her and I said, ‘This doesn’t mean anything to you now, but someday you’re going to use this.’ I remember when a guy fired me off a play once, and then gave me this treacherous little wave as I left, like he was trying to say we were still friends or something; I used that wave in the play Dance of Death when a guy is leaving his wife. You use it all. That’s all you can do.”

“Look,” he continued, “there’s one thing I want you to say in this article. Tell people I didn’t walk off Easy Rider. You can ask [screenwriter] Terry Southern. It’s the truth.”

“I’ll look into it,” I said.

“I’ve never walked off any picture,” he said. “But they said I did. Things were already rough when they said that, but that made it worse.”

“But how about now?” I said. “Christ, you’re in everything. It’s going great.”

“Just scuffling by,” he said, and looked gloomily down at his feet. “Still out here scuffling.”

The next day I talked to Rip’s mother, Thelma Torn, down in Texas. A bright, chirpy woman, she seemed overgrateful for my interest. She told me that Rip’s father had been a “principled Methodist man” who wrote “a philosophical nature column” for the newspaper.

“Dad was probably a Republican,” Rip says, “but he had a progressive strain of Methodism in him. I mean, when you write this, you have to understand that Methodists aren’t Southern Baptists. For example, he didn’t tolerate racism. Not at all.”

Rip went to Texas A&M. It was there that he decided to give acting a try. After graduating from the University of Texas in Austin, where he had transferred after two years, he served a hitch in the army, and after he mustered out, he married Texas actress Anne Wedgeworth and along with their baby daughter, Danae, they moved to New York.

Once there, he managed to hook right into the Actors Studio, and worked with none other than the best director in America, Elia Kazan. Indeed, he was actually under personal contract to Kazan, which must have been every young actor’s dream.

“But he didn’t want to pay me,” Rip said, chewing at his bottom lip and narrowing his eyes so they looked like paper cuts. “He owed me three thousand dollars or something like that, and he said he wanted to take his wife on a trip to Norway, and so I said, ‘OK, I can dig that, but I’ve got a chance to do television, and you know I’ve got a wife and a baby. I need the money.’ But Kazan didn’t want to pay me or for me to do TV. I remember the day I walked out of there, I said to him, ‘I can’t live suspended by the web of your whim.’ Now that’s a terrible line, but I kind of liked it.”

After Kazan, Rip was in demand as an actor. He played on television’s Naked City in a famous episode along with another offbeat, stunning young performer, Tuesday Weld. He did “Playhouse 90’s,” and plays off Broadway. He was being called “great,” another Brando, or Newman—and yet even then there were troubles. Ask any of his friends, Terry Southern or director Don Siegel, or even Rip himself, and you’ll find that he had a serious problem dealing with people he considered inferior to himself. Especially directors. “Hell,” Rip told me one night, shaking his head, “I’d been an MP in the army. I had the responsibility for moving tanks and infantry from one place to the next. I knew how to stage things. I proved it, in the theater. I’ve won two Obies for directing. I know when something is being done wrong, and I can’t stand it. At least I couldn’t [then].”

“The Ripper,” Terry Southern said over drinks at an Upper East Side bar, “is a boss thesp! Yes, R… Bob, if indeed that is your name—aha—keep that in mind! He’s had his problems. One of them being he’s smart. Not a great advantage for an actor. He’ll fight for the small details that make things real. But so did Brando, and, like Brando, Rip is usually right. Is he difficult? Well I can assure you, sirrah, that if you are a second-rate moron of a director, so to speak, then Rip will be most difficult. But, on the other hand, Marty Ritt, Norman Jewison, Sam Peckinpah, Don Siegel, none of them had any trouble with Rip at all. They knew what they were doing.”

Right away, though, Rip developed a “reputation.”

“I was working with Marty Ransohoff, the producer on The Cincinnati Kid,” Southern recalled, “and he kept saying, ‘We need to get a Rip Torn type!’ And I said, ‘Well, er, hummm, Marty, I have this, ah, wild idea. Why don’t we get, this could be too far out for you, Rip himself!’ And he said, ‘Oh no, he’s trouble… no, no.’ But reason prevailed, and we got him.”

“Acting with Rip Torn is an overwhelming experience. I know that sounds like hype, but believe me it’s not. He’s there in the scene, so intense that you feel challenged to give everything.”

The monster egos like Mailer meet Rip dead on, and often lightning and thunder happen, as when Rip and his old friend Mailer made the gossip columns during the filming of Mailer’s Maidstone, a movie about an egomaniacal director (played by the Great Norman himself) who is shooting a movie in the Hamptons. The film’s climactic scene was to be an assassination attempt by Rip, who played Mailer’s half brother Raoul. The story broke that Rip actually cracked Mailer’s skull with a hammer, whereupon the star-director wrestled Rip to the ground and actually chewed a hole in his ear.

“But I pulled the blow,” Rip says now. “You can see it on the film. I pulled the blow or I might have really hurt him. And he chewed on my ear, but not that hard. I remember when we were wrestling around, I said to him, ‘Listen, Dad, I’ve got to make a living with this ear.’ I remember thinking, If he bites me much harder I’m going to have to do him. Yeah, I could see it now—‘Actor Kills Director. The Trial…’”

It is, then, no great secret that Rip Torn has sometimes been his own worst enemy. He admits as much himself, though he always says so defensively, but even so, how bad could he have been? Not one person I talked to ever told me of his pulling off anything really outrageous, like refusing to come out of his trailer or not showing up for a day’s shooting. In fact, I heard just the opposite. He is always on time, always willing to work as late as anyone wants. If he is sometimes bombastic, and egocentric, he is also the ultimate enthusiast, the idealist who, as Loretta Swit, Peter Fonda, and Payday writer-producer Don Carpenter all emphasized, brings up the level of everybody else’s acting to a new pitch. Swit, who replaced Sandra Bernhard on Beer, says, “Acting with Rip Torn is an overwhelming experience. I know that sounds like hype, but believe me it’s not. He’s there in the scene, so intense that you feel challenged to give everything.”

I don’t believe it is hype. I remember him only too well in his films. The sheer physicality of his roles, the surly walk, one eyebrow in the air, the face that was in youth almost beautiful except for a nose which is a little too long and that flat, serpentine mouth.

Breaking a cane over Paul Newman’s perfect face in Sweet Bird of Youth.

Smashing the furniture in Coming Apart.

Singing “She’s Just a Country Girl” with a venomous leer in Payday.

And when he talks, it’s easy to sense the frustration, the anger, at having to be burdened with principles in the first place. The envy a good man has of the big-time bullshit artists who strut the pages of the tabloids, pop off their capped teeth on all the talk shows, selling their diluted, deadening jive.

At bottom, perhaps it’s the envy the good man has of the villain. Which is why, perhaps, he plays the villain so well. Maybe only the good man longs for the flash of the psychopath. “Maybe that was it,” Terry Southern says. “Certain actors had a kind of vulnerability going in; Rip had something else. A kind of danger.”

After the triumphant night at the Kennedy Center, Rip and I had dinner in a restaurant in Foggy Bottom fittingly named the Intrigue. Rip was in a fine mood. We ended up talking about the beginning of what Rip himself and many of his friends think was an unofficial blacklisting that came about because of his friendships with radicals and rockers.

“Listen,” he said, suddenly leaning across the table and staring dead on at me in that intense, frightening style of his, “I used to go hunting with these industrialists, some show biz people. These weren’t very idealistic guys, but they told me straight out, ‘If you keep hanging out with those kinds of people, you won’t work in the business.’”

Rather than tell tales about how wild Rip was, it might be more appropriate to look at how he fought back at whatever “gentleman’s agreement” kept him from getting plum roles. He directed plays, acted constantly off Broadway, and took part in political demonstrations. But he wasn’t simply an actor who let his hair grow, like some other performers of the time.

I talked with him on the phone about what risks he’d taken, but he downplayed them. “Hell,” he said, “people are always saying I ‘chose’ good projects, but they were the only ones offered to me.” However, as his friends readily point out, producers and studio people knew that he wasn’t about to play, say, a heroic Green Beret, and so they never offered him those parts.

But in addition to his public political stance, which I have no doubt hurt his ability to get serious money and studio work, Rip was undergoing another personal crisis that hurt him just as badly. Years earlier he had met, fallen in love with, and married Geraldine Page. Friends talk about their deep and serious relationship, and their home in Chelsea was often a home away from home for West Coast writers, poets, political madmen, and magicians. Yet Rip found the lack of meaningful work doubly frustrating because his wife was one of the most sought-after actresses in the country.

“They say I was mean,” he said to me on the phone recently, “and maybe it’s true. But maybe they made me nasty. All the guys who would come up to me and say, ‘Rip, could you give this script to Gerri? If you would, there’s a part in it for you.’ Or, ‘Would you tell Gerri I love her, pleeeeeease… Could you get Gerri to call me, pleaaaase, Rip.’ I guess I did get nasty then.”

Don Siegel, who directed Rip in Jinxed, acknowledges the actor’s dilemma. “I remember when I was trying to direct Gerri Page in The Beguiled. I wanted her to do a scene a certain way, and she just wouldn’t. We argued about it for a while, you know, and finally I said, ‘OK, Gerri, you do it any way you want, but when Rip comes around to the set tonight, I’m going to call him Mr. Page.’ And Gerri fell down on her knees in front of me, and said, ‘Oh, God, Don, don’t do that. Whatever you want, Don, I’ll do it, but don’t do that—he’ll kill both of us.’”

“Hell,” Rip says now, “I want to cast my own shadow on the world, however paltry it may be.”

And the problems didn’t end there. Perhaps of all the painful indignities heaped on Rip in the sixties, Easy Rider was the most difficult to swallow. The script had been written jointly by Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper, and Terry Southern (though there are still the old arguments about which man did the most work). Terry, who had become Rip’s pal while both of them were working on The Cincinnati Kid, had modeled Easy Rider’s southern lawyer, George Hanson, after William Faulkner’s Gavin Stevens. It was a perfect turn for Rip, and he started discussing the picture with Hopper, Fonda, and Southern with great eagerness. But he didn’t take the role.

“It was a matter of money,” Rip said to me as we walked through the silent Washington streets back toward his hotel. “I asked them for a small percentage of the back end of the picture, and they wouldn’t give it to me. So I told them I couldn’t do the picture. I never signed any contract. l never set foot on the set.”

“That’s what kept me going for so long in spite of everything. The mystery.”

Fonda isn’t quite sure how much money Rip wanted, but agrees that Rip left the picture before he ever was officially in it. “We were sorry not to get him, but he left entirely honorably. He was never anywhere near the set.”

Rip went on to do a Jack Gelber play, The Cuban Thing, and forgot all about Easy Rider. Just another miss. Only this time the near miss for him turned his replacement, Jack Nicholson, into a superstar, and on top of that, in 1975 someone who had been on the set of Easy Rider reported to Bill Davidson of New York Times Magazine that Rip had walked off the picture. This story was later repeated in the Village Voice.

As Rip himself explains: “There is no more serious thing you can accuse an actor of. It can kill him professionally.” At the time it must have seemed like the next-to-last nail in his professional coffin. He sued the Times and the Voice for a quarter of a million dollars, but only received a correction from the Times, which was printed two years after the original article. The Voice eventually printed a feature story written by Ross Wetzsteon that spelled out Rip’s version of the mess.

Coming on top of all the other disasters, the whole Easy Rider affair was probably the low point in Rip’s career. And yet, having missed the brass ring, he soon got another chance at it. He got the perfect role for himself (written by his friend Don Carpenter), that of Maury Dann, the hellish country singer in Payday. Before the film came out, Terry Southern wrote a good-natured piece in Saturday Review predicting that Payday would finally make Rip a great star. But once again, disaster struck. The film got rave reviews, but the distributors somehow fouled up their end of the deal, and the picture died at the box office.

And people wonder why Rip Torn is a tad strange, a bit guarded, and having trouble believing his recently found celebrity will last. Is it any surprise that he still thinks “they” might come and pull the rug out from under him? He has come so close so many times.

“Look,” says Don Siegel, who perhaps has the canniest take on Rip Torn, “he was never the kind of guy who had star quality. He could act ten feet tall for you; he can do any accent, change his body, his look, his eyes, any of that—but none of that is star quality. It’s great acting, but star quality is Clint Eastwood—the kind of guy who causes a traffic jam just walking down the street. Rip never had that. And what’s more, he never wanted that. He didn’t dress like a star; he’d wear any old thing. He didn’t want glamour or any of that. I don’t know for sure what kept him out of pictures for so long. A little of everything, I guess. I think he could have been self-destructive when he was younger; there was a big anger there—and maybe his politics hurt him, but the important thing is that now he’s got his act together, you see. He’s working in every film made, and he’s different in every one of them. He’s a great actor, and, more important, he’s a real person. I mean that. You deal with Rip and you know you’ve met somebody. Someday he might just become a great director. That he could still be.”

And the truth is that his career will always be one of the great oddball stories of American acting. But what of the man himself? Looking back over my notes, my recollections from the last few months, I see a crazy quilt of contradictions.

A man of limitless love and patience for his best friends (many of them no picnic either), but with little for any director he considers his inferior.

An artist rather than a mere “professional,” but an interpretive artist who is usually dependent on the vision of others, which itself must be a constant source of frustration for someone as strong willed as Rip.

An actor who once told me, “Hell, I wanted to be a star. I wanted to be like John fucking Wayne,” but instead spent his time with outlaw artists and radicals.

A loner who searches for the Great Community (he still dreams of a New York Theater, a community of artists).

An egoist whose Southern Methodist modesty and hatred of cant and phoniness have kept him from playing Hollywood games.

In short, a paradox, a romantic with an embattled, fuzzy vision of a better art, and a better world, staggering forward, blasted by psychic land mines, and surprising even himself by landing once again on his feet.

The last time I talked to him he was at his home in Malibu. I could actually hear the waves rolling in over the telephone. “Listen,” I said, “the tough days are behind you. Forget Easy Rider, forget all that bullshit. You’re doing great.”

“Yeah,” he said, and I could hear the old uncertainty creeping back into his voice. “But what if—”

“Give it up,” I said. “You’re doing fine, for God’s sake!”

“They piss me off,” he suddenly said, sounding angry. “Waiting for the damned phone. Hell, I want to get my theater started.”

I laughed out loud. I’d come to know when he was only playing. Some of the old wolf’s wounds have healed in spite of himself. “Goddamn, you’re a puzzle,” I said.

There was a long silence and then Rip surprised me once again. “That’s good,” he said. “It’s like a mystery. Just like art itself. You know, Bob, that’s what kept me going for so long in spite of everything. The mystery. Like … like the taste of a really good meal. Like a deep friendship. Ah, mystery, I love it, goddamn it. What the hell!”