The illustrator Ralph Steadman is a brave man. Not only did he survive humiliation, gunplay and hallucinatory despair through decades of collaboration with the legendarily difficult journalist Hunter S. Thompson, he decided to include as the epigraph to his memoir of those adventures a remark of Thompson’s: “Don’t write, Ralph. You’ll bring shame on your family.”

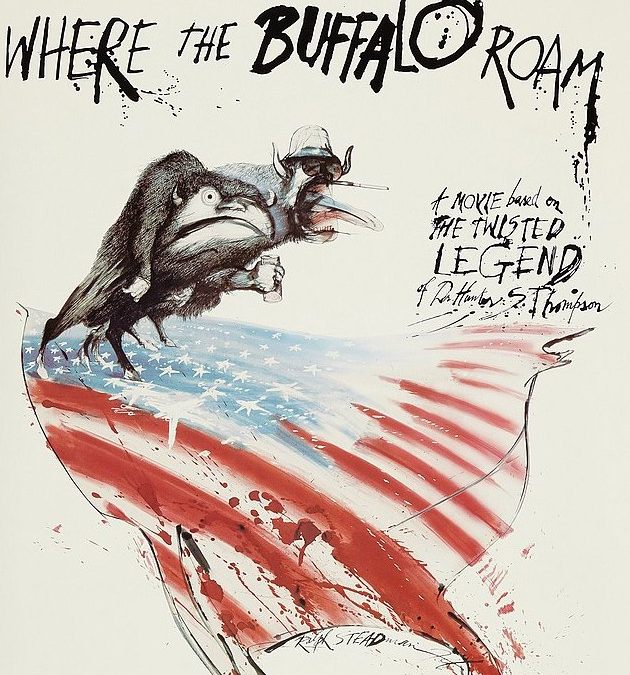

To follow this with a 400-page ramble is the sort of dare the prank-loving Thompson, who committed suicide last year, might have appreciated. For the sake of the Steadman family’s honor, it should be said that The Joke’s Over features a lot of Steadman’s drawings, though reduced too much from their original size. True, these pictures don’t exactly constitute writing, but they are brilliant. Splattery explosions of ink, detonated in the presence of politicians and stolid middle-class citizens, they stand as the mangling visions of a 20th-century Hogarth. When they originally appeared (usually in Rolling Stone), lodged amid Thompson’s prose, the images served as the visual equivalent of the writer’s “gonzo” — a term Steadman defines as “controlled madness” — explorations of America.

As for Steadman’s writing, let’s just say it won’t bring shame to his family, but it won’t slather the clan with glory either. At his best, Steadman, who is Welsh, does a passable imitation of Thompson’s mad rants.

They met in 1970 on Thompson’s home turf of Louisville, covering the Kentucky Derby on assignment for the short-lived magazine Scanlan’s. Steadman’s drawings — vicious caricatures of local residents, including Thompson’s brother — shocked the writer with their predatory vigor. Thompson, soon to become famous for a similar bloodthirsty tack in prose, demanded of the artist: “Why must you scribble these filthy ravings and in broad daylight too? … This is Kentucky, not skid row. I love these people. They are my friends and you treated them like scum.” Their first collaboration ended with the journalist spraying Steadman from a can of Mace. “We can do without your kind in Kentucky. Now get your bags and get out, and take your rotten drawings with you!”

Isn’t this how all great buddy movies begin? Of course they were bound to work together again, and they did a few months later, scoping out the America’s Cup in Newport, R.I. Steadman, a woozy sailor, asked Thompson if he might have one of the little yellow tablets that he assumed the writer had been taking for seasickness. Thompson obliged; a colossal acid trip ensued. The two men decided to jump-start their nonexistent story by spray-painting profanities deriding the pope on the hulls of multimillion-dollar racing yachts. Detected, they panicked, nearly setting a boat on fire with a flare. “Pigs everywhere!” Thompson cried. “We must flee like hunted animals.” Steadman spouted gibberish, which Thompson avidly recorded in his notebook. “That’s good, Ralph. … Go on. What else?”

Steadman ended up catching a flight to New York — no shoes, no socks and a suitcase containing only dirty underwear and a sketchbook. He collapsed at a friend’s home, where a doctor was summoned and shot him full of Librium. “This trip … established a pattern of journalism, if that is what it was, that cemented my friendship with Hunter and laid the ground plan for future assignments. … It remains a defining moment in the evolution of gonzo and, without doubt, a dress rehearsal for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. For Hunter, it provided living proof that going crazy as a journalistic style was possible.”

For a few years in the 1970s, it did appear that insanity was a great career move, that a deranged journalist might fruitfully subvert tired conventions that kept a writer from injecting himself into his work. “He was his own best story,” Steadman writes. The Joke’s Over shows Thompson stumbling and mumbling his way through the early ’70s with the heart of a lawyer for the A.C.L.U. and the brain of an acidhead. His gift then was not so much for intoxication as for high dudgeon. Thirty-five years after its publication, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, illustrated by Steadman at bargain rates (he’s still bitter), holds up as more than a generational relic. Thompson depicts himself as a drug-taking idealist blundering through a nightmare, all the while gripping his sanity as tightly as a steering wheel.

Of course, the gonzo journalism that Steadman claims he and Thompson tripped their way into always amounted to a high-risk proposition. The Joke’s Over makes clear that Thompson was always writing about himself under the influence, that presidential campaigns, for instance, were just another form of intoxicant, a deranging ordeal capable of twisting the mind as surely as a tab of LSD. If the self wasn’t up to snuff, the stories could become as tedious as an overheard cellphone conversation, exercises in terminal narcissism.

The second half of Steadman’s memoir, which spans the years from 1980 to Thompson’s death, is a sad, sloppy affair, puffed out with faxes and bad song lyrics. No writer, it appears, is a hero to his illustrator, at least not when money is involved. Their collaboration floundered over ill-fated projects. Thompson “was much more into deals than personal affection,” Steadman complains.

The prosecutorial details mount. Seemingly against his own wishes, Steadman indicts Thompson on matters large and small. The writer’s feet stank because he wore Converse sneakers without socks. He was unkind to pets; Steadman shows Thompson hauling his mynah bird Edward out of his cage for refusing to speak, and then berating the creature. “There is not a bird-God who is going to save you now, Edward! … You are doomed!” In Steadman’s view, Thompson treated his young son, Juan, with only slightly more finesse, grabbing him by the ear and twirling him about the room “like an average-sized cat.” And yet, conflicted to the last, Steadman writes, “I saw nothing uncommonly vicious.” It was “as though the outward signs of distance and malevolent behavior were put on strictly for visitors.”

Indeed, by the end of his life, Thompson had turned himself into a totem of his own invention, and spent his days rattling the bars formed by the cage of his celebrity. His illustrator tries to put the best possible light on the matter, but betrayed and appalled, he can’t. All told, it’s not a pretty picture.