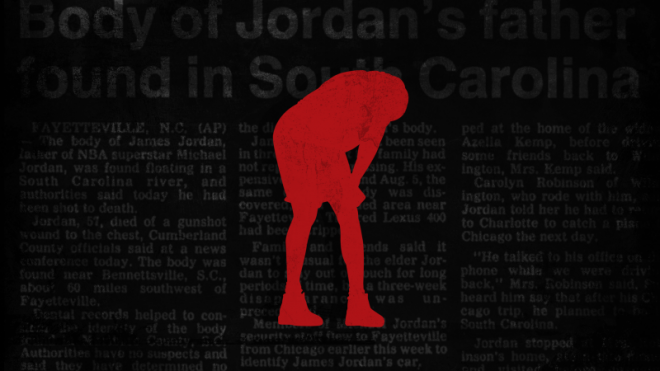

Robeson County Sheriff Hubert Stone knows who killed James Jordan; he knows how, where and why. Sheriff Stone says James Jordan grew tired in the middle of one hot July night and, two hours from home, pulled the $46,000 red Lexus Michael had bought him onto a darkened dirt patch on the shoulder of US Route 74 in one of the roughest, poorest counties in North Carolina—two hundred yards past a Quality Inn on Interstate 95. He fell asleep in the front seat, with the window down and the door unlocked. Two boys, locals out to rob a tourist, walked up on him and shot him dead with one bullet from a .38.

From the dirt-road trailer parks to the Wal-Mart on Fayetteville Road, across a thousand square miles of swamp, tobacco fields and textile mills, Hubert Stone knows where each body is buried and exactly how it came to rest there. This is no small thing: In Robeson County, the bodies are everywhere. During forty-one years of law enforcement in this backwoods war zone, he has, he says, single-handedly investigated more murders than any lawman in the nation, and he recalls only one unsolved case, over in Fairmont a few years back—a man found at home with his face blown away and the offending shotgun in another room of his locked house. For most of his four 4-year terms as sheriff, Stone worked fist-in-fist with former District Attorney Joe Freeman Britt, who was given the title “World’s Deadliest Prosecutor” by the Guinness Book for sending forty-four folks to death row. Twenty-two alleged killers await trial in the county jail right now, not counting Larry Demery and Daniel Green, the two boys accused of doing Jordan.

Hubert Stone walks slowly, an old lion. Glad-handing his way through the corridors of his jail, bearish in his best gray suit, Stone looks like an insurance salesman greeting clients, not a southern county sheriff; his business card is plastic, the calendar on the back printed in tobacco-brown. But his grip is iron, and his small eyes neither blink nor wander. Behind his desk, in an office filled with Christmas offerings—crates of apples and oranges, sacks of pecans, his bounty from a grateful people—Stone talks amiably and with a casual authority, every inch the Man. A sawed-off shotgun rests on a table nearby, and a framed picture atop one filing cabinet shows three lean, fresh-faced deputies in khaki, hunched and grinning around the busted remains of a still. The one in the middle—the only one still alive—is Hubert Stone.

“Alcohol and drugs,” he purrs, tilting back in his chair, his drawl thick and high and wistful. On my first visit, he had brought out a jug of peach lightning for me to sniff; it smelled like orange death.

“In the 1960s, we destroyed more illegal liquor stills in this county than the whole state put together. Then marijuana came along and liquor dried up. Cocaine, we still have a problem with, especially among the Indians. We have it in all three races, but most of the drug dealers that are arrested are one race—Indian. The blacks are on crack. Most of the Indians stay on coke.”

Larry Demery is Indian, one of 40,000 Lumbee in Robeson County; Daniel Green is black.

“Anytime you look down the street and you see a black and an Indian guy, you’ve got crime. You know you’re not supposed to look at things like that, but that’s the way it is,” says Stone. “If they’re running together, something’s up. We always know when we spot a car and see ’em—an Indian and a black—there’s gonna be some crime. We have to keep a firm hand on ’em. It’s not like Philadelphia or New York: Down here, the sheriff is the chief law-enforcement officer.”

There’s a gag order on the lawmen and attorneys involved in the Jordan case, but Hubert Stone doesn’t duck any questions.

“Exit wounds,” he says. “Now, that’s where you bleed. Entry wounds in certain parts of the body, where you’re killed instantly? Few drops of blood. Few drops of blood. They bleed on the inside. The average person like you wouldn’t know that type of thing. The people who read the papers don’t know that. I have seen many victims that was killed that didn’t even have five drops of blood where they was shot.”

So Larry Demery and Daniel Green walked up on James Jordan snoozing in his car and shot him once in the chest, neatly severing his aorta, and drove the body around Robeson County for a few hours, looking for the right place to dump it, and hauled him out of the car, and still there was no blood in the Lexus?

“You’ll find out later there was some blood. There was small amounts.”

According to Stone, the two boys dumped the corpse in Gum Swamp, back over the South Carolina state line, and kept the car for three days, cruising, calling friends and 1-900 sex lines from James Jordan’s cellular phone, using Jordan’s video camera to make a tape of Daniel Green dancing and rapping and styling the NBA All-Star ring and Bulls championship watch Michael had given his old man.

The sheriff has no other suspects, no doubt who killed James Jordan. Forty-one years and only one unsolved killing: Doubt is something outsiders bring with them.

“These guys have been in so much trouble since they was young,” the sheriff says, “they didn’t really think. All they got on their minds was crime.”

As Stone ambles through the jail, the inmates crowd up against the cell windows, fingers looped through the steel fencing behind the heavy glass. A few wave and smile, mouthing inaudible words; most just stare. The trustees carrying lunch trays call out howdy as if greeting a beloved uncle. One pale old man in bright prison orange, with a homemade wooden cross around his neck, puts down his mop to shake the sheriff’s hand.

“How you doin’?” the sheriff asks, smiling into the old man’s wet-eyed nod. “You makin’ out all right?”

At Daniel Green’s cell, Stone stands and waits for Green to be called to the floor-to-ceiling metal grate next to the door. In his orange jumpsuit, the 19-year-old is as black and hard as obsidian, his hair shaved close, the skin tight across the frame of his cheekbones. We shake index fingers through the crossed metal. Three phone calls ago, Green had agreed to talk and to be photographed, just so it was in his own clothes, brought from home.

“I would be allowed to say what I please?” he asked the first time we spoke. “You think they would print it? If I said what l please? Would I have to wear this orange thing? I would hate to be portrayed the way they’ve portrayed me already, this backwards country kid from down South. They’re trying to play me like I’m dumb.”

Green, it turns out, grew up not only in Robeson County but up north, too.

“We’d always go back and forth from here to Philly,” he said, “’cause I got a grandmother who lives down here. When I came down here in third grade, I was the only black student in school. Larry was the only friend I had, man. He was like a brother to me, you know? They made it sound like we just got together to go on a crime spree.”

Two phone calls later, Green had changed his mind: He couldn’t talk about the case in person or have his picture taken.

“I got word not to do an interview,” he said. “Something weird, man—somebody broke in at my house; I don’t know if it was the police or what. They didn’t steal things—the VCR, things like that. They messed up my clothes. If I say something, I don’t know what’s up. It wouldn’t be a good idea for me to talk.”

Had he been threatened?

“Yeah, you could say that. They can’t do anything to me where I’m at—they can’t say that I just got in a fight or somethin’. But I got family that’s out there now. Basically, everybody knows where my family lives at, man, where my fiancée lives at, you know what I’m saying? I hope that what I heard, it was just hot wind, you know? That’s what I’m hoping, anyway. Who else did you talk to about it? Somebody knew who you was, man. Anything strange happen last time you was down here? When you come down, if it’s possible, l wouldn’t stay around here. I ain’t sayin’ be scared. Just be cautious, always.”

Now, through the steel mesh, Hubert Stone and Daniel Green look at each other in silence for a long second.

“I need to speak with you about something,” Daniels tells Stone in a low voice.

“I just wanted to give you the chance to decide to get your picture taken if you want,” Stone replies.

“No, man,” Daniel Green says, glancing my way. He looks younger than 19, his eyes sharp, clear, etched with anger. “But I need to speak with you about something.”

“You gettin’ everything you need?” Stone asks.

“I’m fine,” Daniel answers, standing ramrod-straight. “I’m doing fine.”

“Good.” Stone smiles. “If you need anything, you let me know.”

A hundred steps away, down another hallway, Larry Demery is waiting at his grated door, doe-eyed, watching Stone approach.

Like Daniel Green, he looks younger than in the newspaper photos; he’s 18, copper-skinned and slight, with burred brown hair and a thin mustache sprouting on an otherwise beardless face. Suddenly, his eyes dart down, his mouth turns grim with fear; his body tenses visibly under his tank top. I turn my head to see what he just saw: three inmates glaring poison at him through the window of the opposite cell.

Back in his office, Hubert Stone reflects on Larry Demery and the Lumbee, Demery’s tribe. “People don’t realize that this is the largest organization of Indians east of the Mississippi River,” he says. “I have a situation here—they’re good people, they’re educated people, hardworking people, but they’re violent. Mainly they’re violent among themselves, even in prison. Of course, we have control of them in here, and they’ll humble down just like a kitten once we have them in custody. You saw that Indian boy, how scared he was? Now, you see that boy out on the streets, he’s gonna cause you some pain. He will kill you.”

As for Daniel Green, he had been out of prison only two months when he was arrested for James Jordan’s murder, after serving two years for bashing a neighbor’s skull with an ax handle.

“That one’s just mean inside,” Stone says flatly.

I ask about the first news stories of Jordan’s disappearance, which reported that his wife had spoken with him on July 26, three days after Stone says he was murdered. Deloris Jordan said he didn’t know where her husband was calling from, but he seemed all right. Then, after Green and Demery had been arrested, a convenience-store clerk in Winnabow, eight miles south of Wilmington, North Carolina, and sixty-two miles east of where Stone says Jordan was killed, told police that on July 26 or 27, James Jordan, Larry Demery and Daniel Green had stopped in the store—she remembered the gold trim on the Lexus—and she and Jordan had a brief chat. A bread-truck driver, making a delivery to the store, also recalls the incident. Finally, I say I’ve heard that at least two people whose descriptions don’t match those of Demery and Green were seen running from a red Lexus parked near the intersection of US 74 and I-95 early on the morning of July 23. In September, in fact, a Raleigh television station reported that police were looking for two additional suspects in Jordan’s murder.

Hubert Stone smiles. Mrs. Jordan, the clerk and the bread-truck driver are simply mistaken. The sheriff has no other suspects, no doubt who killed James Jordan. Forty-one years and only one unsolved killing: Doubt is something outsiders bring with them. In Robeson County, every murder case seems to break and close like a well-oiled 12-gauge.

“Robeson County’s hell,” one woman told me before I followed her out to Gum Swamp. “If you want to pull over to the side of the road for a nap and wake up, you don’t do it in Robeson County.”

Leaving me on Pea Bridge Road—the swamp is nothing but a hole in the woods, a maw filled with beer cans, black flies and a trickle of pitchy water—she made a U-turn on the narrow two-lane, braked and rolled her window down.

“You be careful now,” she said, pointing back at the North Carolina border, a hundred yards away. “They’ll kill you over there no matter what color you are.”

Home to 105,000 scattered and roughly divided people—about 40 percent Indian, 35 percent white and 25 percent African-American—Robeson ranks among the worst of North Carolina’s one hundred counties in every category of major human suffering. One quarter of its people live in official poverty—per capita income is $8,900—and most of the rest just get by. The bleaker the statistic, the more clearly it breaks down by race: Poverty claims 15 percent of the county’s white children, more than one third of the Indian children and more than half of the black children. The schools may be the state’s worst: Fewer than 60 percent of the county’s adults graduated from high school, and the dropout rate is rising. A federally funded program pays to station an armed police officer at each of the county’s six high schools.

Robeson County’s violent crime rate is 154 percent higher than that of similar-sized rural counties in North Carolina; the murder rate is 135 percent above that of Raleigh, the capital, a city of 220,000. The only place in the state that rivals it for sheer lawlessness is Charlotte, a burgeoning New South metroplex, home to nearly half a million people.

But the most remarkable aspect of Robeson County is its reputation for corruption and cheap cocaine. If tobacco remains the county’s main cash crop, drugs are close behind, tax-free, no land required.

“We believe today,” Assistant U.S. Attorney William Webb told reporters in 1987, “that cocaine trafficking involves tens of millions of dollars in that county. Every time we think we’ve got the players identified, something will happen to show us things are larger than we thought. We’ve bought ounces of pure cocaine for $1,100. That’s the same price or even less than you’d find it being sold for on the streets of Miami. Very seldom in Robeson County do you see cocaine cut below 50 percent purity. There’s so much coke at such good prices, people can be choosy.”

Webb was directing a federal-state task-force probe into Robeson County’s drug trade, an investigation that lasted nearly two years and netted seventy-five arrests, nearly all small-crime dealers. Nothing has changed, folks here say—not the price, not the purity and certainly not the abundance.

Interstate 95 runs the length of the East Coast, nearly 2,000 miles, from Miami to Maine, through Daytona and Jacksonville, through Savannah and the Carolinas, through Richmond and Washington, D.C., Baltimore and Philly, New York City and Boston—a river of commerce and death, four and six and eight lanes wide. In the right lane, shiny-new trailer homes travel north from Florida, red flags and wide-load signs flapping behind. In the space between their aluminum shells and the plywood wall paneling, some are stuffed with white powder.

“If I’m a major drug dealer,” says Connee Brayboy, editor of The Carolina Indian Voice, “in order for me to operate, anyplace, I’ve got to have some protection from law enforcement.”

For thirty-nine miles, beginning at North Carolina’s southern border, I-95 runs through Robeson County, halfway between Miami and Boston. There are twelve exits on this stretch of highway, four of them in Lumberton, the county seat. Exit 14 is just south of town, before the spray of lit billboards tells you there’s a small city here, not just another service-road strip. Here I-95 crosses US 74, the Andrew Jackson Highway, the only major road connecting I-95 with Charlotte to the west and Wilmington and the resort towns along the Atlantic coast to the east. Cocaine and cash change hands and turn the corner, in large lots, right here. Right here, if Hubert Stone is right, James Jordan died.

With so much coke at such good prices, it’s not hard to find people who accuse Hubert Stone and his department of being involved in the business.

“Has it been absolutely established that Michael Jordan’s father was alive when these young guys came to his car? He’s from North Carolina; everybody in North Carolina knows about Robeson County. Why didn’t he go to a motel? Why didn’t he at least go to a lighted parking lot, ninety seconds away?”

“If I’m a major drug dealer,” says Connee Brayboy, editor of The Carolina Indian Voice, “in order for me to operate, anyplace, I’ve got to have some protection from law enforcement. Here, you get you a deputy sheriff, and you promote him.”

She pauses, laughing.

“I don’t care,” she says. “It might as well be me in the line of fire. I have yet to find anyone who’s serious about investigating what’s going on in this county. It comes down to big business, and my people are expendable. It’s my people getting destroyed. That’s not to say my people don’t deal drugs; I’m not about to say they won’t and they don’t. But the whites put up the money—you don’t start a drug operation on credit. The men who is making money on drugs in this county is not on the streets dealing it.”

Webb’s task force did indict one deputy for the theft and distribution of a pound of cocaine, stolen from an evidence locker. The deputy was acquitted, but not before testifying under oath that one Robeson County drug dealer cut Hubert Stone $300 in protection money for every ounce of cocaine he sold.

“The biggest problem we have,” U.S. Attorney Webb said in 1987, “is we can’t get closer than second- or third-hand information. We’ve caught enough people who move in those circles. We ask them how they can operate so openly. But we haven’t gotten anybody who’s about to say they paid a law-enforcement officer.”

The sheriff shrugs off any question of drug corruption in his department.

“Accusations have been made against law enforcement ever since I’ve been here,” he says. “I’ve been used to that. Malcolm McLeod, he was sheriff here for twenty-eight years before me, and they made all kinds of accusations against him.”

Some of these accusations have made national news. Early in 1988, Eddie Hatcher and Timothy Jacobs, two local Tuscarora Indians, seized the offices of the county newspaper. Armed with shotguns, they held the staff of The Robesonian captive for ten hours, asking the world for help; they’d already tried the DEA and the FBI, Hatcher claimed, and now their own lives were threatened because, he said, they had hard evidence—maps of drop-off points, names of coke-dealing deputies and details of their transactions—of the sheriff’s department’s hand in the local drug trade. Hatcher also listed eighteen recent murders of Robeson County blacks and Indians; many, he alleged, had been drug-related, including the death of one small-time dealer, unarmed and shot dead by Deputy Kevin Stone, Hubert’s son. A coroner’s jury deliberated six minutes before concluding that the killing had been “an accident and/or self-defense.”

Hatcher demanded that the North Carolina governor impanel an investigation; he also asked that he and Jacobs not be turned over to the Robeson County Sheriff’s Department upon their surrender. The governor agreed, and Hatcher and Jacobs released their hostages unharmed. A federal jury found them not guilty of federal hostage-taking and firearms violations, whereupon the state of North Carolina immediately charged them with fourteen counts of kidnapping. Jacobs served four and a half years. Hatcher, thrice denied parole, is serving an eighteen-year sentence; Amnesty International calls him a political prisoner.

Two months after the hostage-taking, Julian Pierce, a Georgetown University-educated Lumbee lawyer running against District Attorney Joe Freeman Britt for a superior-court judgeship, was killed in his home by three point-blank 12-gauge blasts, a few weeks before the election. Dead, Pierce won the race by almost 2,000 votes. Britt, who derided what he called the “sympathy vote,” is still the superior-court judge.

Sheriff Stone took three days to determine that Pierce had been slain by his fiancée’s daughter’s former boyfriend, a young Lumbee named Johnny Goins. Before he could be arrested, Goins was found dead with his brains on the wall and an open shotgun between his legs.

Sheriff Stone called Johnny Goins’s death a suicide.

“I can assure the world there was no political involvement in this case,” Stone told reporters afterward. “I think the people of Robeson County will know that it’s just another murder.”

Yet many of the people I spoke with—some still expressing fear for their lives—told me there was evidence that Pierce had been assassinated. Pierce had claimed to associates that he’d discovered information about county law enforcement’s drug activities. As judge, he had promised, he would do something about them.

Two sources said they’d presented evidence of all this to State Bureau of Investigation agents, who simply ignored it. And several drew parallels between the handling of Pierce’s killing and the hasty investigation of James Jordan’s murder.

“Has it been absolutely established,” asked a former U.S. Department of Justice investigator who’d studied the Pierce killing, “that Michael Jordan’s father was alive when these young guys came to his car? He’s from North Carolina; everybody in North Carolina knows about Robeson County. Why didn’t he go to a motel? Why didn’t he at least go to a lighted parking lot, ninety seconds away?”

Another man, a lawyer who worked for the defense in the Hatcher trial, spoke with me twice about Jordan’s murder, then asked me not to contact him again.

“This is not something to play with,” he said. “These kids were set up. I’ve done civil rights cases all over the South, but Robeson County is a whole different thing—the first resort in Robeson County is to kill you. When I was down there, I wore a bulletproof vest, carried a shotgun everywhere I went. I went underground. They’ve got three organizations down there—from Miami, Chicago and New York—that vie for territory, and then you’ve got a major government presence, all of them involved in drugs. When Eddie Hatcher took the newspaper over, he thought the sheriff was the problem, that he had drug dealers on his payroll. But that was the tip of the iceberg, and I mean iceberg.”

He stopped there, telling me that his phone was tapped. I offered to meet with him, and he said he’d check back to arrange a time.

“I didn’t get a whole lot of sleep last night,” he told me the next day. “It’s just too dangerous. It would just put me back in the line of fire. Just so I’ve advised you how bad the situation is. You need to proceed with caution. I don’t have any hard evidence that James Jordan was not killed by the two guys arrested, but the circumstances would be consistent with a lot of other things. I wish you luck.”

Inside the double-wide trailer where Larry Demery lived his whole life, a shallow stainless-steel bowl of water with pine needles in it sits simmering on a kerosene heater, flavoring the close air. Like most of Robeson County’s residents, the Demery family lives in no town, just back off a winding two-lane, at the end of a rutted trail, snugged up against the woods.

“I ain’t big on talkin’,” says Larry Demery Sr., looking away when we shake hands.

Wiry and dark, both pockets of his snow-white shirt packed with smokes, he stands off to one side of the kitchen, a menthol curled into one palm, listening.

His 15-year-old son, Shaun, lean and muscular in a red T-shirt and black jeans, offers a glass of Mountain Dew. He’s antsy, waiting for a cousin to come by to go duck hunting, pacing the kitchen, watching the light fall outside. The dining-room table is set for dinner, with pink cloth napkins held by silver rings inscribed with a scrolled D.

As he paces, Shaun’s sneakers make a sucking noise on the kitchen linoleum. His father’s face blanches with each step.

“Get off there in them shoes. Right now.”

“But,” Shaun says, and that’s all he says, leaving the kitchen in two strides. His father’s hands have dropped to the waist of his blue work pants, where they tug once, hard, on the buckle of his belt.

Virginia Demery, small and plain, is the talker. She’s also the one who has filled these walls with testimony to God and family, with framed Psalms and holy pictures, Indian statuary and prints of warriors on horseback.

“A mother knows her son,” she says. “Larry Martin had done some things he shouldn’t have—I know that. But there’s no way he’d do something like that. No one on this earth will ever convince me those two boys killed that man. Not in a million years, no matter how this comes out.”

“The thing about this mess,” Larry senior mutter from his blind in the kitchen, “is that Robeson County’s always been a black eye in this state. So nobody pays no real attention.”

I ask Mrs. Demery if she minds if I identify Larry junior as a Lumbee.

“That’s fine,” she says, nodding. “That’s what we are.”

The Lumbee lived in Robeson County a long time before the blacks, before the whites. The first waves of settlers bypassed the rude swamps for kinder, drier land. Over time, though, stragglers arrived—runaway slaves, vagabonds, exiles of every stripe—and were assimilated. Today, some Lumbee have eyes of blue or green or gray, blond hair and light skin; others are brown-skinned, with hair so black it gleams. Nearly all of them are Christian, many evangelical. “Discovered” in the eighteenth century, they were thought to be the mongrelized descendants of the Lost Colony of Sir Walter Raleigh, which had vanished from the Carolina coast around 1585. In truth, they were simply American Holocaust survivors, the entrenched remnant of various ancient native tribes, most long gone, whose bloodlines merged here. They were welded into one people by the same sweep of European disease, alcohol and armed Christianity that obliterated their separate languages and cultures and nearly all of their kin. Centuries later, they are unique in this country, a triracial native tribe whose memory and shadow stretch back to the bloodthirsty birth of a nation.

Today the Lumbee are battling Washington for tribal recognition and economic assistance, as they have for most of this century. The Bureau of Indian Affairs insists that the Lumbee don’t fit the definition of a tribe—they have no reservation, no language and no religion of their own. The well-established tribes, particularly those in the western U.S., have little sympathy for the Lumbee; even some local traditionalists, especially among the Tuscarora, belittle them for seeking handouts from the white man and despise them for their embrace of Christianity.

Robeson County has one predominantly middle-class Lumbee town of 2,200—Pembroke, home of a state university that was the nation’s first Indian school—but for the most part, they are scattered and impoverished. Many Lumbee men drive hours every day, to Charlotte or Raleigh and back, to hang sheetrock in apartment complexes and subdivisions for $7 or $8 an hour; the women often work in cut-and-sew textile shops for half that.

Despite their reputation for violence, the Indians—both Lumbee and Tuscarora—were the nicest folk I met in Robeson County. But they do not hide their rage, or their despair, about the fate of their people, and the way they have been—and continue to be—painted as savages. Larry Demery is only the most recent confirmation of that fare, both a threat and a totem of what the future promises his people.

The newspaper box around the corner from Hugh Rogers’s one-man law office on North Court Square in Lumberton sells The Robesonian; a hand-lettered sign taped above the coin slot warns “THIS MACHINE IS BEING WATCHED. IF YOU ARE CAUGHT STEALING PAPERS YOU WILL BE INDITED [sic].” Directly across the street stands the county courthouse, four stories of brown brick fronted by a forty-foot spire commemorating the county’s Civil War dead.

Hugh Rogers doesn’t think Robeson County is a snake pit, but Hugh was born and raised in Lumberton.

“Hell, we ain’t no worse than anywhere else around here,” he says, chuckling, a chinless, genial bumpkin with dirty-blond hair and razor stubble. His eyes, a thin blue, look nearly washed of color.

He’s been practicing law here for thirteen years, mainly defending the indigent. The court appointed him counsel to Larry Demery. I ask Hugh if he’s ever tried a capital-murder case before.

“Oh, yeah.”

And?

“Well, I’m oh-for-one,” he says, still grinning, “but I’m counting on the North Carolina Supreme Court to straighten that one out.”

Neither one confessed to killing James Jordan; each maintains that Jordan was already dead when he first saw him. Both were charged with first-degree murder, conspiracy and armed robbery.

Hugh Rogers has no objection to the death penalty per se. “As a citizen,” he explains, “I think it’s necessary. For retribution, if nothin’ else. As a defense lawyer, hell no—maybe for somebody else on some other day, but not my man, not this day.”

Hugh’s “somebody else” so far in the Jordan case has been Daniel Green. When news of the arrests broke, Hubert Stone and agent of the SBI—full of pride for cracking the case so quickly and eager to emphasize what they called the “totally random nature” of the killing—fed the media a daily feast of damning evidence against Demery and Green. Hugh went to bat for his man by telling the press flat out that Green had pulled the trigger on James Jordan.

Not only was Roger apparently disclosing privileged information, but his words also threatened to doom Daniel Green. Green’s attorney, Public Defender Angus Thompson, responded immediately by asking the judge to order Hugh to keep his mouth shut.

“I’d like to know on what basis he made that statement,” Thompson said. “Unlike Hugh Rogers, I am not the kind of attorney who wants to showboat for the media and deal with fiction and trash.”

“Well,” Hugh tells me when I ask about the dustup between the two defense attorneys, “Angus doesn’t have my bills. I gotta pay rent for this office; he works for the government.”

A judge included both attorneys in his gag order, but Rogers remains unfazed. He’s been phoning Hunter S. Thompson at the Woody Creek Tavern in Aspen, Colorado, to get him to cover the case. One time, Hugh says, he just missed Dr. Thompson, or so the bartender said.

Why Hunter Thompson?

“The spirit of gonzo jurisprudence is alive and well in Robeson County,” Hugh answers.

I wonder aloud if Hugh is angling for a change of venue.

“We’re thinking about that. I want it back up in the mountains, on the border of Appalachia, where there’s no running water, no phones, no newspapers. The Jordan family has less contacts in that part of the state. And the thing that bothers me with a jury here is that they’re just getting over Julian Pierce and Eddie Hatcher. We’ve pretty well gotten back on our feet, back to normal, and a jury here might be predisposed to punish somebody for screwin’ up the works.”

This is what we know. James Jordan left a widow friend’s house near Wilmington a little after midnight on the twenty-third of July, after an evening spent visiting folks in and around his hometown.

“He said he was going to stop working and enjoy the rest of his life,” Carolyn Robinson told reporters. She had fixed Jordan dinner that night, and a care package for his ride home. She overheard him calling his secretary to set up his next day’s schedule: He and his son Larry had a business meeting near Charlotte; afterward, they’d fly to Chicago. He also had phoned his sister in Chicago on July 22 to say he’d be visiting after driving back from a friend’s funeral in Wilmington.

Somewhere between Wilmington and Charlotte, a 200-mile drive he had made dozens of times, James Jordan was murdered.

On August 3, a fisherman found Jordan’s body thirty miles west of the crossroads where Stone says he died. The corpse, ravaged by the heat and the swamp—the pathologist who examined him could estimate only that he’d been dead between one and three weeks—was taken to the closest town, McColl, in Marlboro County, South Carolina. No one knew the dead man’s name, or that he had turned 57 on July 31.

On August 5, the red Lexus 400 turned up smashed and stripped in Fayetteville, thirty miles north of Lumberton. The tow-truck driver who brought it in told reporters that he’d seen a business card from a Chicago Lexus dealership in the car, along with Jordan-family photos and a letter from a charity thanking Michael Jordan for his help. Somehow, though, the Cumberland County investigators took seven days to trace the registration to Michael Jordan.

On August 12—immediately after the car was identified, nearly three weeks after James Jordan failed to show up in Charlotte—the Jordan family finally filed a missing-person report. Michael Jordan flew members of his security staff from Chicago to Charlotte to help search for his father.

The Marlboro County coroner, Tim Brown, saw the story of James Jordan’s disappearance that night on the CBS Evening News and phoned the Cumberland County sheriff. By 3 A.M. on Friday, August 13, Brown had James Jordan’s dental records, which matched the John Doe he had cremated a week before. With no refrigeration unit, Brown says, and no way to preserve the remains, he’d had no choice but cremation; he saved the .38 slug he’d pulled from James Jordan’s chest, Jordan’s fingertips and $10,000 worth of dental work.

By midnight Saturday, the mystery was over: Hubert Stone had Larry Demery and Daniel Green in custody. The State Bureau of Investigation had traced the calls made from James Jordan’s cellular phone to a friend of Green’s in Fayetteville. For seven hours before they were placed under arrest, Demery and Green were interrogated separately, without attorneys, by State Bureau of Investigation agents and a Robeson County detective.

If they didn’t start talking, the boys say they were told, both would wind up on death row.

Neither one confessed to killing James Jordan; each maintains that Jordan was already dead when he first saw him. Both were charged with first-degree murder, conspiracy and armed robbery. Sheriff Stone called a Sunday-morning press conference to assure the world that James Jordan’s death was a random killing and that the perpetrators were behind bars in Robeson County.

Case closed.

If James Jordan did pull onto the shoulder of US 74 at 2:30 A.M. on July 23, it’s likely that no one will ever know why. Sheriff Stone told me that it’s a popular place for truckers and such to pull over for a mid-state nap, but no one stopped during the nights I sat parked there in August and September and October and December. Maybe that’s the result of James Jordan’s killing, but the people I talked with in Robeson County scoffed at Stone’s claim. “I have a problem with the particular place where he was stopped,” Connee Brayboy told me. “They move drugs there all the time. James Jordan was either a part of what goes on in this county or he runned up on something in that particular location that he was not to see, and live. If he accidentally saw something that required his life, they didn’t check his credentials before they killed him. They don’t do that here.”

I asked an assistant U.S. attorney in the Raleigh office if he knew that the very spot where James Jordan ended up is a notorious drug crossroads. “I’m aware of that,” he replied. “But I’m told that there’s no good place to park down there.”

Eight months after the murder, there is no physical evidence that Larry Demery and Daniel Green killed James Jordan. Detectives say they found a .38 in Daniel Green’s trailer, but ballistics tests showed that “the bullet recovered from James Jordan was damaged to the point where it couldn’t be conclusively linked to the gun they recovered.”

“I’m just tired of seeing all this crap on TV about me,” Demery explained. “It’s all lies. I’m not saying I’m a perfect angel. I’m just not capable of murdering somebody.”

“Anywhere else but here it couldn’t happen that way,” Green says. “I’m not saying this to put the South down, but Robeson is the corruptest county anywhere. All the pressure was on them. I think what happened is that they just took a little bit and tried to build, make more out of, it. They didn’t care if I was guilty or not—they was gonna arrest somebody for it.

“I’m not protecting nobody—l’m in here because I wouldn’t talk to begin with, but that’s because I have no way of knowing for sure, you know? I’m not going to get up under oath and swear a lie that could take somebody’s life. But, like I said, man, especially with Stone and all that, I can’t have my name associated with nothin’ this early. I just know that somebody here is gonna say ‘Well, he’s tryin’ to get outside of us, get away from us, so we’re gonna have to do somethin’ to show him that we ain’t playin’—you know what I’m saying?”

Larry Demery, who would not speak with me, claimed in a November phone call to the High Point Enterprise that he had dropped Green off at the Quality Inn at 2:30 A.M. on July 23 and noticed the Lexus parked on 74 on his way home. Twenty minutes later, he said, Green drove up in the Lexus with Jordan’s corpse. Demery said he helped Green dump Jordan’s body in Gum Swamp but didn’t ask his friend what happened before that.

“I’m just tired of seeing all this crap on TV about me,” Demery explained. “It’s all lies. I’m not saying I’m a perfect angel. I’m just not capable of murdering somebody.”

Green denies this version of events.

“You can quote me on that,” he says. “I know that’s not what happened. I’m not saying Larry’s the bad guy. I think stuff just happened. I think stuff just happened quick, whatever it was.”

On October 5, the Robeson County district attorney had announced that the state would seek the death penalty for both boys.

On October 6, Michael Jordan retired.

“l always said I wouldn’t let you guys run me out of the game,” he said to the throng of reporters at his press conference that day. “Don’t think for a minute you had anything to do with it.”

Michael Jordan has reasons for feeling run out of the game he has spent his life playing, but ultimately they have little to do with the press. He retired while the NBA was investigating—for the second time in two years—his gambling activities and his friendships with assorted North Carolina hustlers and thugs, including men with bulk-cocaine connections.

In October 1992, after lying about a $57,000 cashier’s check he’d given to a Charlotte man named James “Slim” Bouler—a previously convicted cocaine dealer on trial at the time for conspiracy to distribute cocaine and laundering drug money for a major Charlotte drug ring—Michael was subpoenaed and forced to testify that the money had been a debt from a three-day golf-and-poker weekend at Hilton Head, South Carolina.

Michael’s wrath at the media for reporting his gambling problems waxed red after James Jordan’s death.

Before that, in February 1992, $108,000 in cashier’s checks from Michael turned up in the briefcase of yet another of his Hilton Head gambling buddies, Eddie Dow, who had been murdered earlier that month. Dow was a Charlotte bail bondsman and, according to testimony at Bouler’s trial, a coke dealer. Dow’s brother and his attorney both said that the Jordan checks were drawn to pay off another weekend gambling loss.

Michael refused to comment but testified in court that, during these long weekends of poker, golf and dice, there never had been any talk of or use of drugs. How often, he was asked in court, did he go on these outings with these men? Two or three times a year since 1987, he said.

The NBA conducted a hasty investigation, and Michael Jordan himself was summoned to New York City in March 1992, to explain the situation at league headquarters. Commissioner David Stern listened carefully, sifted through all the evidence and warned him to be more careful about his associates. The second investigation—begun in June 1993, after Michael allegedly ran up over a million dollars more in gambling losses to a San Diego businessman—ended quietly two days after he retired.

Michael’s wrath at the media for reporting his gambling problems waxed red after James Jordan’s death.

“Throughout this painful ordeal,” Michael said in a statement issued on August 19, “I never wavered from my conviction that Dad’s death was a random act of violence. Thus, I was deeply disturbed by the early reports speculating that there was a sinister connection [between Michael’s gambling activities and] Dad’s death. I was outraged when this speculation continued even after the arrest of the alleged murderers. These totally unsubstantiated reports reflect a complete lack of sensitivity to basic human decency.”

Right. No connection whatsoever. James Jordan, a fast-living man with a 1985 felony conviction for taking a kick-back, business debts and gambling problems of his own, father of the most celebrated man on the planet, disappears for three weeks, during which time his birthday falls, and nobody—not his wife and not the world-famous son who considered him a best friend—files a missing-person report. He winds up shot dead in the dark of hell’s backyard, dumped into a swamp in another state and burned as an anonymous pauper. His car is found sixty miles away, where the police take nearly a week to identify it. His widow says he called three days after he supposedly died. Within forty-eight hours of his identification, a backwoods sheriff produces two of an endless supply of blank, born-violent minority youths and puts them on trial for their lives after another open-and-shut investigation of another random killing in Robeson County.

Larry Demery and Daniel Green will stand before the law and Court TV and most likely be found guilty, no matter where the trial is held. Demery has a prayer of avoiding lethal injection: He’s scared to death and talking. His version of what happened on July 23 keeps changing in small, telling details, but each revision adds to the burden of Daniel Green’s presumed guilt.

“I think he may turn state’s evidence,” Daniel says during a January phone call, after Demery told a local reporter that Green may have been involved in drug dealing, that Green wanted to swap the Lexus for guns, drugs or money and that prison had “put hatred in him or something.”

Green isn’t bothered by what Demery says or worried about his fate.

“I can’t be mad at him. I’m mad I’m in here, period. I don’t think I should be in here. I’ll be honest with you: I came out of prison cynical. About the whole world in general, and our justice system specifically. But I’ve never been hard. Even when I was in prison, I ain’t never tried to play hard. I tried to get my education. I wrote poems and stuff.”

Green had become a Muslim in prison, had gotten his GED, taken some correspondence courses from the University of North Carolina and been accepted at three colleges. He had been reporting regularly to his parole officer and wooing his fiancée, who now writes him every day. He seems serene, laughing as he denies what Demery alleged.

“It’s all a lie,” he says. “I could say something now, and I could prove it and make him look foolish—him and his lawyer, everybody. But I’m going to say it when I go to court, at the right time. They ain’t got proof. They don’t have the proof.”

Did someone besides Green or Larry Demery kill James Jordan?

“I don’t know,” Daniel answers. “I know Daniel Green didn’t. That’s the only thing that I could swear to.”

Larry Demery became a father last September, five weeks after he’d been arrested. A photo of his daughter, Taylor Yvette, sits on the TV in the living room of the Demerys’ trailer, framed in silver.

“I couldn’t throw my life away by taking someone else’s,” he told the newspaper. “I’ve got too much to live for.”

Even if he turns state’s evidence, Demery may well get life. Either way, Daniel Green probably is headed to death row, where he’ll wait with 117 others, nearly half of them African-American. Someone killed James Jordan, and Sheriff Stone has all the proof Robeson County has ever required: two poor boys, one Indian, one black. The absence of physical evidence or witnesses, the conflicting dates and possible sightings, the botched Lexus investigation, the uncertainty as to the time and place of death—such things don’t fit and therefore don’t matter.

Michael Jordan hopes to play baseball; then, in twenty years, maybe the PGA Senior Tour. He has no comment.

[Featured Illustration: Sam Woolley/GMG]