Oh, golden, yellow light shimmering on Reggie Jackson’s chest! Yes, that’s he, the latest member of the American League Champion New York Yankees, and he is standing by his locker, bare-chested, million-dollar sweat dripping from his brow, golden pendants dangling from his neck. God, he looks like some big baseball Othello as he smiles at the gaggle of reporters who rush toward him, their microphones thrust out, their little ninety-eight-cent pens poised, ready to take down his every word. But somehow, it’s hard to ask the man questions … certainly not such standard ballplayer questions as “How’s the arm?” or “Toe hurt?” …for not all ballplayers are Reggie Jackson, whose golden pendants catch the sunlight filtering through the steamy Fort Lauderdale clubhouse windows and reflect dazzlingly into your eyes. What are these priceless reflectors? Well, first, there is a small golden bar with the word “Inseparable” on it, a gift from Reggie’s Norwegian girlfriend, and gyrating next to that memento is a dog tag—the inscrutable Zen koan (though slightly reminiscent of the Kiwanis Club), “Good Luck Is When Hard Work Meets Opportunity.” And, finally, there is the most important bauble of all, an Italian horn that Reggie tells a reporter is supposed to keep the evil spirits away!

Evil spirits? Egads. What evil spirits can be following Reggie Jackson? The man has been on three World Series Championship teams (Oakland A’s 1972–1974), has led the league in RBIs (1973: 117), home runs (1973: thirty-two, 1975: thirty-six) and was the American League’s MVP in 1973. Since then he has topped his on-the-field-feats by playing out his option under Charles O. Finley, and refusing to sign with his new club, the Baltimore Orioles, until they gave him a gigantic raise. Finally came the coup de grace: signing with the New York Yankees for three million big ones. Reggie is expected to be the biggest thing to hit New York since King Kong. So where are the evil spirits?

“No evil spirits, actually,” Reg says, answering a newsman’s question. “Just in case, you know? Hey, could you move that mike out of the way? Shoving it up my nose like that is sooooo uncomfortable….”

The little man yanks his mike back.

“I am not merely a baseball player,” Reggie says to another reporter, who nods gravely. “I am a black man who has done what he wants, gotten what he wanted and will continue to get it.

“Now what I want to do,” he adds, “is develop my intellect. You see, on the field I am a surgeon. I put on my glove and this hat….”

He picks up the New York Yankee baseball hat. Itself a legend. Legendary hat meet legendary head!

“And I put on these shoes….” Reggie points down to his shoes. “And I go out on the field, and I cut up the other team. I am a surgeon. No one can quite do it the way I do. But off the field… I try to forget all about it. You know, you can get very narrow being a superstar.”

Reggie removes his cap. “I mean, being a superstar … can make life very difficult, difficult to grow. So I like to visit with my friends, listen to some fine music, drink some good wine, perhaps take a ride in the country in a fine car, or … just walk along the beach. Nature is extremely important to me. Which may be just about the only trouble I’ll have in New York. I’ll miss the trees!”

Then, in his quiet, throaty voice, Reg politely says he must be off to the training room.

“Terrific,” a jaunty reporter says as Reggie leaves. “He’s so terrific. He’s the kinda guy you don’t want to talk to every day … because he gives you so much. It’s like a torrent of material. He overwhelms you!”

“Yes,” I say. “But how do the other guys on the Yankees feel about having a tornado in their presence? I heard Thurman Munson and some of the others gave him a chilly reception.”

“No problem,” says the reporter. “All that stuff about problems on the team is just something somebody wrote to sell papers. Hell, Reggie hasn’t even been here for a week. There hasn’t been time for resentment yet!”

Reggie Jackson has taken over so totally that it’s almost as if the other players were rookies who had yet to prove themselves to the press.

The next day after practice, Reggie Jackson is once again standing by his locker, once again surrounded by reporters, who ask him to reveal his “personal philosophy of life.”

I look down the seats before lockers and see last year’s Yankee stars sitting like dukes around the king. Next to Jackson is Chris Chambliss. Remember him? He hit the home run that won the pennant for the Yanks. But no one seems much interested in this instant (though brief) hero’s developing intellect or his reflections on recombinant DNA, which happens to be the subject Chambliss is discussing with Willie Randolph. And down the line a little farther is old gruff and grumble himself, Thurman Munson. Today he rubs his moustache, and stares at the floor, looking like Bert Lahr in the Wizard of Oz. Folks aren’t rushing to ask him about the philosophical questions that are addressed to Jackson, yet Munson is the acknowledged “team leader.”

And across the room is Catfish Hunter, the wise old Cat, and businesslike Ken Holtzman. Their combined salaries are enough to send up a space shot to Pluto, but no one is asking them if they like to recite Kahlil Gibran. It’s strange, a little dreamlike. There is the Superteam, but if this first week is any example, Reggie Jackson has taken over so totally that it’s almost as if the other players were rookies who had yet to prove themselves to the press.

Now, Jackson says goodbye to the reporters, and tells me he is going outside to sign a few late-afternoon autographs. Would I like to come? Certainly.

And so we stand our by the first baseline while the fans crowd around, pushing and shoving and holding up their cameras.

“Smile, Reggie,” says a woman with a scarf on her head, tied up so she looks like she has two green rabbit ears.

Reggie produces a semi-smile.

“You have such white teeth,” she says.

Jackson turns to me and raises his eyebrows, then moves along signing scraps of paper and baseballs when a man on crutches is pushed precariously close to the edge of the stands. Jackson stops signing and demands that the other fans help the crippled man. The fans do what he says.

Finally, after Reggie has signed endless signatures, a young boy says, “Thank you, Mr. Jackson.”

Reggie stops, looks up at me and says: “You sign a million before anyone ever says thank you.”

Jackson comes strutting into the room. Not a self-conscious strut. Just his natural superstar strut. He can’t help it if he is bigger than all indoors.

On that perfect exit line, Reggie does a perfect exit. He picks up a loose ball and flips it to the crowd, who cheer and applaud. Waiting for Jackson to get his rubdown, I ask Sparky Lyle, who is seated in front of his locker: “How’s it going?”

“Great,”’ says Lyle. “I may be leaving tomorrow. We are only about two hundred and fifty thousand dollars away from one another.”

Perhaps not the best time to ask him about the new three-million-dollar superstar. Bur duty must be done.

“I don’t think we need him,” Lyle says. “Not to take anything away from his talents, but what we really needed was a good right-handed hitter. A right-handed superstar.”

Jackson comes strutting into the room. Not a self-conscious strut. Just his natural superstar strut. He can’t help it if he is bigger than all indoors.

Lou Piniella strides across the room and says, “Hey, Reg, How you doing?”

“How you doing, hoss?” Reggie says affably.

“I’m not the horse, Reg,” Piniella says, with a good deal of uncertainty in his voice. “You’re the hoss … I’m just the cart.”

Jackson smiles, trying to pass the remark off as a joke.

Jackson and I enter the Banana Boat Bar, and he undoes his windbreaker just enough to reveal the huge yellow star on his blue T-shirt. Around the star are the silver letters that spell out superstar! At the bar, he discards the jacket. All around us people start staring and the waitresses start twitching in their green Tinkerbell costumes.

We order Lite beers, and Reggie gives me a pregnant stare and says, “If I seem a little distant, it’s because I got burned once by Sport magazine. They wrote a piece which said I caused trouble on the team. That I have a huge ego. That I only hit for a .258 average. That I wasn’t a complete ballplayer. They only say that kind of stuff about black men. If a white man happens to be colorful, then it’s fine. If he’s black, then they say he’s a troublemaker.”

I tell him that I have no intention of showing him as a troublemaker. As far as I’m concerned the league could use fifty more Reggies, and fifty fewer baseball players who sound like shoe salesmen.

But almost before I’m finished, Reggie has forgotten his fears. “You see,” he says, “I’ve got problems other guys don’t have. I’ve got this big image that comes before me, and I’ve got to adjust to it. Or what it has been projected to be. That’s not ‘me’ really, but I’ve got to deal with it. Also, I used to just be known as a black athlete, now I’m respected as a tremendous intellect.”

“A tremendous intellect?” I say.

“What?” says Jackson, waving to someone.

“You were talking about your tremendous intellect.”

“Cosell was insecure. He thought I was trying to put him down, make him look bad by correcting him. He made quite a stink about me to the big people at ABC, but they took up for me…I was just being myself and it got me in trouble.”

“Oh, was I?” Jackson says. “No, I meant … that now people talk to me as if I were a person of substance. That’s important to me.”

I mention Jackson’s reportage on the Royals-Yankees pennant playoffs last year for ABC, saying that most of my friends felt that Reggie had done a much better job of analyzing the motivation of the players than Howard Cosell. What’s more, he did it in the most hostile atmosphere imaginable, with Cosell constantly hassling him and chiding him for defending Royals’ centerfielder AI Cowens on a controversial call.

“Well, that is part of my problem,” says Reggie. “I do everything as honestly as I can. I give all I have to give. But I don’t let people get in my way. Cosell was insecure. He thought I was trying to put him down, make him look bad by correcting him. He made quite a stink about me to the big people at ABC, but they took up for me. I really wasn’t trying to compete with him. I was just being myself and it got me in trouble.”

Jackson smiles, sits back and folds his arms over his superstar chest. A second later we are joined by Jim Wynn, who at thirty-five is trying to make a comeback with the Yankees: Once a tremendous long-ball hitter known as “The Toy Cannon,” Wynn has been faltering, and certainly he can’t have more than a year or so left. He orders a drink, and then Reggie and he begin to talk about hitting in Boston’s Fenway Park.

“You are gonna love the left field fence,” Reggie says.

“I know I will,” Wynn says. “If they play me, you know I’ll hit some out.”

The waitress comes back to Reggie and says, “Whitey Ford appreciates your offer of a drink, bur says he would rather have your superstar T-shirt.”

But he doesn’t sound convinced. There is a lull in the conversation and then Wynn looks over at Reggie, and says, “You know, Reggie, I hope my son grows up to be like you. Not like me. Like you.”

Wynn smiles in awe at Jackson, and I realize that for all their professionalism, the Yankees are just as subject to the mythology of the press as any fan. Just by showing up, Jackson has changed the ambiance of the locker room. And no one yet knows if it’s for good or ill.

As I ponder, two of the original mythmakers appear at the Banana Boat—Mickey Mantle, now a spring batting coach, and his old crony, manager Billy Martin. Soon they are settled into drinking and playing backgammon, and when they are joined by Whitey Ford, Jackson hails a waitress and sends them complimentary drinks. The waitress comes back to Reggie and says, “Whitey Ford appreciates your offer of a drink, bur says he would rather have your superstar T-shirt.”

Jackson breaks into a huge smile, peels off his shirt, and runs bare-chested across the room. He hands the shirt to Ford, and then Ford, in great hilarity, takes off his pink cashmere sweater and gives it to Jackson. A few minutes later Reggie is back at the bar, the sweater folded in his lap.

“That’s really something, isn’t it!” Jackson says. “Whitey Ford giving me his sweater. A Hall-of-Famer. I’m keeping this.”

He smiles, looking down lovingly at the sweater.

On the Yankees the old-timers still retain their magic, even to the younger stars like Jackson. In a way it is easier for him to relate to them than his own teammates. For they were mythic, legends, as he is … In fact, their legends are still stronger than Reggie’s, coming as they did back when ugly salary disputes didn’t tarnish both players and managers.

This becomes even more apparent when Jackson moves to the backgammon table to join the crowd watching Mantle and Martin play one of the most ludicrously bad, but hilarious, games in recent history. Both of them beginners and slightly loaded, the two men resort to several rather questionable devices. The object of the game is to get your men, or chips, around the board, and into your opponent’s home, then “beat them off the board.” The man who gets all his men out first wins. (You throw a pair of dice to decide how many spaces you can move.) Martin rolls a seven and quickly moves nine spaces. Jackson and Ford laugh hysterically. Mantle rolls his dice, moves the properly allotted amount, and then simply slips three of his men off the board and into his pants pocket. Martin, busy ordering drinks and taking advice from Reggie, misses Mantle’s burglary, which gives Mickey a tremendous advantage in the game. Martin’s next roll lands him on two of Mantle’s men and sends them back to the center bar. Mantle rolls the dice, orders another round of drinks and, while Martin chats with the waiter, takes four more of his chips off the table and puts them under his chair. Mantle chuckles as Martin, unaware of what has happened, rolls the dice. Reggie tries to control his laughter—unsuccessfully—the mirth bursting out of him. And now everyone is laughing, Mantle so hard that tears are streaming down his face. Martin suddenly notices that Mantle, despite weaker rolls of the dice, already has fewer men on the board.

“You bastard!” Martin shouts. “Where are all your chips?”

Mantle protests his innocence with great vigor but Martin reaches down and pulls out the evidence from under Mantle’s chair. Mantle screams in mock surprise, and then throws up his hands. “Hell, Billy,” he says, “you were beating me even though I was cheating.”

“You bum,” says Martin, “You bum. I’m just too good. I’m a winner.”

“Nobody can beat Billy,” Mantle says as he beams at his old buddy.

“It all flows from me. I’ve got to keep it all going. I’m the straw that stirs the drink. It all comes back to me. Maybe I should say me and Munson … but really he doesn’t enter into it.”

Reggie is still laughing, shaking his head, and I can’t help but feel that he has missed something. Mantle, Ford, and Martin have a kind of loyalty and street-gang friendship that today’s transient players don’t have time to develop. Soon Mantle and Martin are involved in another humorous game, and Reggie goes back to the bar. Alone.

Minutes later I join him and try to gauge his mood. What did he feel watching Mantle and Martin? In a second I have my answer, for Reggie starts talking and how he is less the showman. He seems to be talking directly from his bones:

“You know,” he says, “this team … it all flows from me. I’ve got to keep it all going. I’m the straw that stirs the drink. It all comes back to me. Maybe I should say me and Munson … but really he doesn’t enter into it. He’s being so damned insecure about the whole thing. I’ve overheard him talking about me.”

“You mean he talks loud to make sure you can hear him?”

“Yeah. Like that. I’ll hear him telling some other writer that he wants it to be known that he’s the captain of the team, that he knows what’s best. Stuff like that. And when anybody knocks me, he’ll laugh real loud so I can hear it….”

Reggie looks down at Ford’s sweater. Perhaps he is wishing the present Yankees could have something like Ford and Martin and Mantle had. Community. Brotherhood. Real friendship.

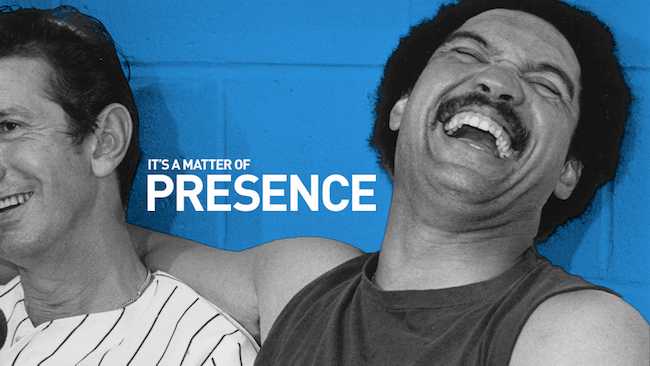

“You see, that is the way I am. I’m a leader, and I can’t lie down … but ‘leader’ isn’t the right word … it’s a matter of PRESENCE.”

“Maybe you ought to just go to Munson,” I suggest. “Talk it out right up front.”

But Reggie shakes his head:

“No,” he says. “He’s not ready for it yet. He doesn’t even know he feels like he does. He isn’t aware of it yet.”

“You mean if you went and tried to be open and honest about he’d deny it.”

Jackson nods his head. “Yeah. He’d say, ‘What? I’m not jealous. There aren’t any problems.’ He’d try to cover up, but he ought to know he can’t cover up anything from me. Man, there is no way….I can read these guys. No, I’ll wait, and eventually he’ll be whipped. There will come that moment when he really knows I’ve won … and he’ll want to hear everything is all right … and then I’ll go to him, and we will get it right.”

Reggie makes a fist, and clutches Ford’s sweater: “You see, that is the way I am. I’m a leader, and I can’t lie down … but ‘leader’ isn’t the right word … it’s a matter of PRESENCE….Let me put it this way: no team I am on will ever be humiliated the way the Yankees were by the Reds in the World Series! That’s why Munson can’t intimidate me. Nobody can. You can’t psych me. You take me one-on-one in the pit, and I’ll whip you….It’s an attitude, really… It’s the way the manager looks at you when you come into the room…. It’s the way the coaches and the batboy look at

you…. The way your name trickles through the crowd when you wait in the batter’s box…. It’s all that…. The way the Yankees were humiliated by the Reds? You think that doesn’t bother Billy Martin? He’s no fool. He’s smart. Very smart. And he’s a winner. Munson’s tough, too. He is a winner, but there is just nobody who can do for a club what I can do…. There is nobody who can put meat in the seats [fans in the stands] the way I can. That’s just the way it is…. Munson thinks he can be the straw that stirs the drink, bur he can only stir it bad.”

“You were doing it just a few minutes ago over there with Martin, weren’t you?” I say. “Stirring a little.”

“Sure,” says Jackson, “but he has presence too. He’s no dummy. I can feel him letting me do what I want, then roping me in whenever he needs to… but I’ll make it easy for him. He won’t have to be ‘bad’ Billy Martin fighting people anymore. He can move up a notch ’cause I’ll open the road. I’ll open the road, and I’ll let the others come thundering down the path!”

Jackson sits back, staring fiercely at the bar. A man in love with words, with power, a man engaged in a battle. Jim Wynn resumes his seat next to Reggie and watches him with respect. An ally.

But, I wonder—are there any others?

Billy Martin is sitting in his office at Yankee Stadium South. He is half dressed and his hair is messed, but for all that he still has what Jackson called PRESENCE. Now he runs his hand through his hair and laughs: “I couldn’t lose to Mantle, could I?” he says.

“You had him psyched.”

Martin laughs again and nods. “And he was trying to act like he wasn’t mad”

Mantle comes in the door sipping coffee and looking about two years older than the night before. “You know,” he says, “I woke up this morning, and I had me a whole pocket full of them white things!”

After we finish laughing, I ask Martin if he thinks there will be any problems having Reggie Jackson on the team.

Martin, who as Reggie himself said is “no dummy,” smiles and asks, “What kind?”

“Like team leader problems?”

Martin shakes his head: “Not a chance. We already have a team leader. Thurman Munson.”

I walk into the locker room and sit with Catfish Hunter in front of his locker and talk about Reggie. Catfish shoots a stream of tobacco juice on the floor, and shakes his head slowly, philosophically. “Reggie is a team leader,” he says. “The thing you have to understand about Reggie is he wants everyone to love him.”

For a second I think Cat is going to elaborate on this theme, but he holds back, chooses a new path—a safer one. “I mean,” he says, “he can get hot with his bat and carry a team for three weeks. He’s always ready to go all the time.”

Hunter squints at me as if to say, “That’s all, my friend. I’m staying out of this one.”

Chris Chambliss’s locker is right next door to Reggie Jackson’s. The men literally rub elbows when they dress. Yet when I ask Chambliss how he feels about Reggie, he says, “I haven’t had a chance to talk to him yet. I think he’ll help the ball dub. Most of the rumors you have heard are untrue. Still, we do have a lot of personalities on this team… things could happen. I doubt it. But they could.”

I catch Thurman Munson as he comes in to practice. An hour late. I wonder if he isn’t having some kind of psych battle with Jackson. Which star arrives on the field the latest? Gruffly, he declines to talk to me until after practice, and then he declines again for some thirty minutes. Finally, he nods me over and I ask him about Jackson.

“What are you asking me for?” he says. “Why does everybody ask me?”

“I’m nor singling you out,” I say. “I’ve asked quite a few others. But there has been talk that you two will have problems competing as team leader.”

Munson shakes his head, makes a face. “No. No way. And what difference does it make if I’m not ‘team leader’? There are a lot of leaders on this ream. We’ve got a lot of scars. They are all leaders. As far as Reggie goes, he’s a good player. He’ll help the club. Has a lot of power.”

“How about jealousy over his salary?”

“No,” Munson says, “I don’t care about that. He signed as a free agent. I hope he makes ten million dollars. Is that all?” Munson turns away and begins to talk to a businessman about a shopping center they hope to build in Florida.

It’s late in the afternoon and Reggie Jackson is taking extra batting practice. The only people left on the field are Thurman Munson and Chris Chambliss. And a young pitcher, a rookie who is new to me.

Jackson fouls off a couple of pitches, and Chambliss looks at Munson and says, “Show time!” There is a real bite in his kidding. “Hey, says Munson, “are we out here to see this?”

Jackson digs in and fouls off a few more.

“Some show!” says Munson. “Real power!”

Jackson tries to laugh it off, and finally connects on a pitch. It falls short of the fence, and Munson and Chambliss smile at one another. Munson steps into the cage, but Jackson hurries into the locker room.

I am about ready co leave, and I thank Reggie for his cooperation, but he seems disturbed by my going. “Listen,” he says, “I’d like to know what the guys thought of me. You talked to them. How about telling me?”

“Just wait until I get hot and hit a few out, and the reporters start coming around and I have New York eating out of the palm of my hand … [Munson] won’t be able to stand it.”

“Okay,” I say. “I’ll meet you back at the Banana Boat.”

An hour later, at the Banana Boat, I tell Jackson that Lyle had said the team didn’t need him, that Lyle said it was nothing personal, but the Yankees needed a right-handed hitter more. Then

I tell him that Munson had denied there was any problem, and I mention that Chambliss had said, “I haven’t had a chance to talk to him yet.”

“Yeah,” says Jackson. “You see it’s a pattern. The guys who are giants like Catfish, the guys who are really secure … they don’t worry about me. But guys like Munson….It’s really a comedy, isn’t it. I mean, it’s hilarious….Did you see him in the batting cage? He is really acting childish. Like the first day of practice he comes up to me and says, ‘Hey, you have to run now … before you hit.’ You know he’s playing the team captain trying to tell me what to do. But I play it very low key. I say, ‘Yeah, but if I run now I’ll be too tired to hit later,’ and Munson says, ‘Yeah, but if you don’t run now, it’ll make a bad impression on the other guys.’ So I say, ‘Let me ask the coach,’ and I yelled over to Dick Howser, ‘Should I run now or hit?’ and Howser yelled, ‘Aw, the hell with running. Get in there and hit.’ So that’s what I did. It really made Munson furious. But I did it so he couldn’t complain. Listen, I always treat him right. I talk to him all the time, but he is so jealous and nervous and resentful that he can’t stand it. If I wanted to I could snap him. Just wait until I get hot and hit a few out, and the reporters start coming around and I have New York eating out of the palm of my hand … he won’t be able to stand it.”

Jackson delivers all this with a kind of healthy, competitive and slightly maniacal glee. It’s as if he has said to himself, “Okay, they aren’t going to love me. So I’ll break ’em down. I’ll show them who’s boss.” And he might. I can’t help but think that the situation would be a lot healthier if the other Yankees had come to him.

“How has Chambliss been treating you?” I ask.

“Standoffish. They all have. You see Piniella in there yesterday? He said that stuff about me being the horse and him being the cart. That’s how they feel. Bur at least he talked to me. That was a kind of a breakthrough. That and the thing with Whitey, with the sweater. That was good, too.”

“Maybe you are overreacting,” I say. “It is a new year, and everyone has heard about your legend, and they feel like they can’t be the ones to come up to you and try to break the ice because then it will look like they are trying to kiss your ass, and they’ll feel embarrassed and self-conscious.”

Jackson nods hopefully. “Yeah, it could be that. I know it could be. Say, did you talk to Billy Martin about me?”

“Yeah,” I say. “He told me that the Yankees had a team leader.”

“Yeah? Who?”

“Munson.”

Reggie laughs ruefully.

“But maybe he’s gotta say that,” I say. “It wouldn’t look good to say you are the ream leader this early. It would hurt Munson’s pride.”

“That’s right,” Jackson says. “I just want you to know that [coach] Elston Howard came up to me today and said, ‘No matter what anybody says, you are the ream leader.’ So I think there is some real heavy stuff going on. But it is weird. You know, up until yesterday Martin had hardly said two words to me. Bur he has made me feel I’m all right. Still, I don’t understand it.”

“It could go back to your verbal ability,” I suggest. “I mean, a lot of athletes are suspicious of people who can talk well. It makes them feel dull and stupid, so they resent the other guy and get hostile toward him.”

“Right,” says Jackson. “That’s true. I’ve been through that one before. But you know … the rest of the guys should know that I don’t feel that far above them….I mean, nobody can turn people on like I can, or do for a club the things I can do, but we are all still athletes, we’re all still ballplayers. We should be able to get along. We’ve got a strong common ground, common wants….I’m not going to allow the team to get divided. I’ll do my job, give it all I got, talk to anybody. I think Billy will appreciate that….I’m not going to let the small stuff get in the way….But if that’s not enough … then I’ll be gone. A friend of mine has already told me: ‘You or Munson will be gone in two years.’ I really don’t want that to be the case … because, after all is said and done, Munson is a winner, he’s a fighter, a hell of ballplayer … but don’t you see….”

Reggie pauses, and opens his hands in a gesture that seems to imply, “It’s so apparent, why can’t Munson and Chambliss and all the rest of them understand the sheer simplicity … the cold logic?”

“Don’t you see, that there is just no way I can play second fiddle to anybody. Hah! That’s just not in the cards….There ain’t no way.”

Postscript

It was a hot summer day in June 1977, and I was on the Long Island Railway coming in from my house in the Hamptons. For the past month I had holed up in this old red-shingled house on the bayside just a few miles south of Montauk. Jann Wenner had come over one night to tease me about not having a house, or a compound, like he did on the ocean side. But the truth was I loved it where I was. Tall grass, swans that swam up to the beach every night, and plenty of room for my dog, Byron, to run around chasing rabbits. My girlfriend, Robin, loved it too and it had been a wonderful month, writing my screenplay, Cattle Annie and Little Britches. I wanted and received no phone calls. This was, of course, before the days of the computer so there were no e-mails, no phone machine, and no one had my number. I didn’t want to be bugged by my magazine editors. The truth was I was kind of burned out interviewing endless people and now that I was making money writing scripts that seemed a better way to go. (Little did I know I would have another eight years of struggling before I cracked Hollywood. It’s a good thing we don’t know what lies before us because if someone had told me I would be looking forward to eight more years of living hand to mouth I might have turned to a life of crime instead).

So there I was with my typewriter, perfect sunsets, swans, Byron and on weekends gorgeous Robin, who had a job at Ballantine publishing. Everything was fine and dandy.

I never once gave a thought to Reggie Jackson.

Why? Because in those days magazines, like Sport, had a three-month lead period. That meant you handed the piece in three months before it was going to be published. In fact, I had done three or four other pieces after it for other magazines, plus my screenplay, and some short fiction. Reggie Jackson was the last thing on my mind.

One day, however, I wanted to go into the city to see some of my friends. I was getting a little cabin fever writing all day and night, and I wanted a little city-action. So I took the train into town and got off at Penn Station. I was headed to a cab on Eighth Avenue when I happened to see the sports page of the New York Post on the magazine rack. The headline was in big bold letters.

It read: “Furor on the Yankees!!”

“Robert,” he said. “Where the hell have you been? The whole goddamned world wants to talk to you!”

I walked over to the magazine stand and picked it up. As I read, my heart beat faster and faster. I don’t recall the exact words but the gist of it was: “A bomb exploded in the Yankee clubhouse today due to an article on Reggie Jackson written by Robert Ward of Sport magazine….”

“Holy shit,” I said, and ran for a payphone. I called Berry Stainback; he wasn’t in. But Dick Schapp was.

“Robert,” he said. “Where the hell have you been? The whole goddamned world wants to talk to you!”

“They do?” I said. I’d had some violent reactions to my writing before but nothing like this. Dick then listed five radio shows and three TV shows that wanted me on. Not to mention every newspaper in the country.

“It’s great,” Dick said. “We haven’t had a story like this in a long time!”

“Right!” I said. “Great!”

“Why don’t you come up here now and we’ll plan on what we’re going to do first!”

“Is it okay if I get to my apartment and change clothes first?”

“Yeah, sure,” Dick said. “But get over here. The Yankees are going nuts. I talked to Phil Rizzuto about twenty minutes ago.”

The thing was, even though I was a tough guy reporter, who really would print anything no matter what the fuck anyone said to me (and especially if they threatened me), I was still an All American kid, who had always loved Phil “Scooter” Rizzuto. The idea that I had done something that would make him hate me really bothered me. I mean, hell, I had his baseball card!

“So what did Phil say?” I said, buffering myself for the shock.

“He loved it,” Dick said. “Phil’s just like all the old Yanks. They can’t stand Reggie.”

That was only a partial relief. I didn’t want people to hate Reggie. The truth was, I kind of felt sorry for him. And did the old Yanks hate him because he was black and smart? Or was it because they couldn’t take his big ego, his fur coats, and all the rest? Or were they just jealous of him because it was his time in the sun and theirs was over?

That was one problem with journalism that I never got over. You stirred up a hornet’s nest, but then left to do other pieces and never really knew what the real answers were.

Ah, well, I told myself, you should feel good about it. You’ve only done one piece on the New York Yankees and it’s become world famous.

Such are the small victories of freelance writers.

I am writing this little postscript to my most famous piece in 2010. Another world. A million other stories have taken place in sports and maybe half a million on the Yankees since the Reggie story of 1977. I thought the world had long forgotten what I’d written.

Then one day in 2005 I got a call from ESPN Sports. They were doing a piece on Reggie for their Top 100 Athletes of the Twentieth Century series and they wanted me to be interviewed for it. I said sure, and soon I was on an hour-long documentary about Reggie. But what made it really sweet was they let me tell my side of the story. For years Reggie had been lying about how I made up all the quotes I attributed to him. But on the documentary I got to tell my own side of the story, the true side. I heard from mutual pals that Reggie was furious.

Well, that had to be the end, I thought. No more of the Reggie Jackson story.

Wrong again. In 2006, Jonathan Mahler, a brilliant New York journalist, called me and said he wanted to get my quotes for his new nonfiction book, Ladies and Gentleman, the Bronx Is Burning. Mahler’s idea was to take all the major stories of 1977 in New York, the Son of Sam terrorizing the streets, the blackout and subsequent riots, and the Yankees winning the World Series, and tie them together in one great book. I was happy to be part of it. And this time I was able to cite the first interview Reggie gave after the piece came our. He told the late Pete Axthelm in Newsweek that

he didn’t deny saying any of it. He said,”He (meaning me) caught me off guard.” Which was true, except that a mouth like Reggie’s doesn’t seem to have a guard on it.

Only later when teammates had ostracized him, and basically hated his guts did he start saying that I made it all up.

No one on the Yankees believed him then and I doubt any of them do now.

I told all of this to Mahler, who to his credit used it in his excellent book. He was the first guy to get it a hundred percent right.

That was fun. All those years later to have the truth written by a first-rate writer.

Well, I thought, that must truly be the end. I had been on Reggie’s own documentary and I had been in Mahler’s brilliant book.

But even more fun was to come.

One day in 2007 the phone rang again. It was a casting director who said she was looking for Robert Ward, the author of the Reggie Jackson piece.

“That’s me,” I said.

“Well, ESPN is doing a docudrama-miniseries of Jon Mahler’s book and we need someone to play you.”

“Who are you thinking about?” I said. I thought they were asking me my opinion of who would be best. After all I had been a writer/producer on Hill Street Blues and the exec co-producer on Miami Vice. I knew many younger actors. I tried to think of someone who could play me in the ’70s. Had to be someone in their mid thirties, brilliant, handsome, witty… etc.

“We were thinking you could play it,” the casting woman said.

“What?”

“The director Jeremiah Chechik saw you in the doc about Reggie’s life and he thought you would make a good Robert Ward.”

“Yeah, but I’m thirty years older than I was then!”

“That doesn’t matter,” she said. “You’re a print person, and a producer. No one knows what you look like.”

“Yeah,” I said. “I guess you’re right.”

“You interested?”

“Why not?”

“There’s only one thing,” she said.

“What’s that?”

“You have to read for it.”

A long pause as I considered the philosophical and Sartreian ramifications of this.

“What? I have to audition to play myself?”

“That’s right,” she said. “How do we know you will be any good at playing you?”

“Good point,” I said. “I might be a lousy me.”

A day later I found myself at the casting offices, sitting in a room with a couple of character actors, who were auditioning to play ME!

For the first time I began to feel a little worried. What if one of these jokers was more like me than I was? That would be a fine thing. A few minutes later I was sitting in a room across from the two casting directors. They handed me a script. The scene I had to play had two people in it, myself and Reggie Jackson. The speeches were written by a screenwriter, but the lines the two men were saying were directly out of my article written thirty-one years earlier.

The whole thing had a surreal feel to it. Bur it was also as easy as falling off a log. I just acted like myself, sitting at the bar all those years ago. I was tense and excited just like I was back then. Of course, for different reasons: My motivation in the old days was: “I have to get this goddamned story or I can’t pay the rent!” Now my motivation was, “I have to get this part or I’ll look like a bleeding fool. No freaking actor is going to play me better than I do!”

So, in each case, I had to tamp down my feelings and play it cool. I read the scene with one of the casting directors. When I was done they looked at one another, shook their heads. Then they asked me to do it again, which I did.

Halfway through the second time the senior casting person stopped me. Christ, I thought, she doesn’t think I can do it. I’ve failed to be me. I’m not me at all. Holy Christ, who am I?

But she looked at me and smiled. “You know what?”

“What?”

“You’re really good at playing you. You’ve got the job.”

“For real?”

“For real. Not everybody can play themselves. They get uptight but you’re a natural. You fly out to Connecticut day after tomorrow for your first scene. Congratulations.”

I hugged them both and headed out to my car. It was unbelievable. The Reggie Jackson piece had been written about in thirteen books, including The Top of the Heap, a book with the best pieces ever written about the Yankees since their inception, it was still constantly quoted on television during games, it had gotten me into Reggie’s ESPN documentary, and now I was playing myself in the docudrama. I sat in my car and shook my head.

Mickey Mantle and Billy Martin were gone. Reggie couldn’t play himself because he was too famous, and too old. The Son of Sam, David Berkowitz, was in prison. I would be the only original person in the entire miniseries who was actually there when it all went down in 1977.

It was amazing. “Reggie Jackson in No Man’s Land” was the piece that wouldn’t die.

I ended up going back and forth from L.A. to Connecticut three times. They flew me to Hartford, then drove me down to the set in Mystic. A young actor named Daniel Sunjata was playing Reggie, and he did a remarkable job. When we were sitting at the Banana Boat Bar set, I kept feeling like Rod Serling was going to show up.

Most of my lines were in the first episode, and it was a gas meeting John Turturro who played Billy Martin, and Oliver Platt who played George Steinbrenner. The few times I’ve acted (I’ve been in three movies, one documentary, and two TV shows) I’ve always been stunned by what royalty even the lowest actor is on the set. I’ve been the executive producer on Miami Vice and Hill Street Blues and no one pampered me, or worried whether I was hungry or would like to meet a fan. No one cared about the executive producer, even though he and the other writers are the guys who write the entire script, work with the directors, hire the actors, and so on. Writers and producers are treated like peasants compared to the actors who the average lighting person thinks of as the “real talents.” It was great being taken care of by the makeup and hair people. “Can we gee you another cup of coffee, Robert?” Damn if anyone ever got me coffee on Miami Vice.

Though people who work in the business know better, they get carried away by the idea of the noble artist actor as much as any TV fan. What’s odd is that I’ve seen producers have the same worshipful attitude toward the actors they created.

If an actor is famous he eclipses everyone around him. On the set, that is. But off the set, unless he’s a superstar, he has very little power.

I knew all this but enjoyed being thought one of the stars of the show while I was there. The third night there, the great Yankee third baseman, Craig Nettles, paid us a visit. He took one look at me and said: ‘’I’m the straw who stirs the drink.” We all laughed and had a ball together.

I heard rumors that Reggie was coming but he never showed up.

Well, now that my piece has been in every conceivable form, except a feature movie or Broadway play, I guess the furor is finally over. But then again I thought that twenty years ago and look what’s happened.

Who knows where and when “Reggie Jackson in No Man’s Land” will strike again? If there are any Broadway producers our there who want me to sing my part in the musical version, check out my website. I stand ready.

[Featured Image: Sam Woolley]