Let’s take a moment to celebrate the one and only Gil Schwartz who passed away a couple of days ago. Some of his grief-stricken pals were kind enough to offer some of their memories and we are the richer for it.

Take it away, fellas:

Mike Sager: (Longtime contributor to Rolling Stone, GQ, and Esquire; majordomo of The Sager Group)

Writing as Stanley Bing, Gil Schwartz might well have been the most successful pseudonymous author/journalist of our times.

Known for his scathing, insightful, humorous, and well-written dispatches from behind the lines of corporate America, Bing was, for three decades, a regular columnist for Esquire and then Fortune, where he held down the back page. He is the author of thirteen business books (including Crazy Bosses and Sun Tzu Was a Sissy) and three suspense novels (including You Look Nice Today and Immortal Life (A Soon To Be True Story).

All the while, Schwartz kept his day job, spending nearly 40 years in upper management at broadcast titans CBS, Viacom and Westinghouse Broadcasting, retiring in November 2018 as the Chief Communications Officer of CBS Corporation. Though one of his Esquire collegues would out him to the New York Times in the late 1990s, Schwartz’s corporate bosses happily sanctioned his double life. Even in the shark-infested waters of his high-stakes milleu, he was much beloved.

Schwartz died unexpectedly of natural causes in his home on Saturday morning, a heart attack according to family sources. He was 68. He’d only just begun his retirement. It wasn’t even Covid-related. Just a sudden and unexpected death by natural causes. The thing that makes all men of a certain age walk on eggshells. You can go to bed one night with a little bit of shoulder pain and an upset stomach and have no clue it’s your last night on earth.

I first found Stanley Bing in the mid-1980s, when he wrote a front-of-the-book column for Esquire called The Strategist. I was in my late twenties and hoping to write for Esquire myself someday. His column was all about life inside corporate culture, a subject for which I had no earthly interest, and no little bit of distain, having quit law school after three weeks to pursue a career in the arts.

But Stanley Bing’s column had a way of engaging me. He was funny, he was endearing, he was a craftsman of words, he was able to render something very specific into something universal. I’ve always thought great writing was about a person’s ability to clear a path from their heart and mind to their fingertips. Stanley Bing had that.

It was less than two years ago now that I actually met Schwartz/Bing for the first time. We share in common a beloved editor, David Hirshey, the guy who first allowed me in the door at Esquire so many years ago. Besides having an editorial relationship, it turned out the pair are lifelong pals, part of a foursome of friends (including the journalist Fred Schruers and the Hollywood writer and producer Roger Director) that go back more than four decades. By fortune or design, all four live with their wives within a short distance of one another on the west side of Los Angeles. They are the best kind of friends: the kind you know and who know you. There is a ton of crap slung around, but never any bullshit.

I met Schwartz only a handful of times, all but one at his modest but impeccably restored craftsman house. He took me in like an old friend. His wife Laura Svienty is tall and lovely and kind. She was equally warm and welcoming, only in a quieter, prettier package. Besides the several Boys’ Nights I was privileged to join—Gil and the grill—I attended a small gathering on New Year’s Eve 2019. It was the very first time I’d spent that particular night outside my own habitat in three decades.

On each of these occasions, I was basically the fifth Beatle to the foursome (which regularly became an eightsome with the inclusion of the wives, who were equally woven into the fabric of the friendship). Though I am by nature a loner, being included felt like a salve. With my own lifelong pals 2600 miles away on the other coast, it felt comforting to be enfolded by this crew.

After we first met, I was man-crushing a little bit, so I Googled Mr. Schwartz/Bing. Like many writers, those early years of reading a particular magazine you love (and desperately want to be published in), sticks in your psyche. To me, Bing would always be The Strategist. Honestly, when he’d jumped to Fortune, I’d lost track of him.

Gil and his wife Laura Svienty in Santa Monica, 2018. “To say I’m punching above my weight is an understatement”

I was not surprised to learn Schwartz had started as a poet, playwright and actor. He did improv. He did Shakespeare. He had three plays produced in Philadelphia and New York. An accomplished guitarist, it’s said he could play a tune on any instrument, from a clarinet to a ukulele to a piano. He was photographer with a particular penchant for birds, travel and food. For a time, he wrote a column called “Ask Gil” for Seventeenmagazine, in which he masqueraded as a 17-year-old boy, giving girls advice on how to deal with the opposite sex.

Clearly, this Schwartz/Bing guy was a genius and a Renaissance man. And clearly, he had a ton of creative energy he was able to productively channel. But what set him apart for me was his warmth and good humor. You could tell he was secure in himself. And that meant he had the time for you.

The last time I met the Fab Foursome was, as usual, at the Schwartz residence. The date was March 12, 2020. The night before, I was having dinner with my son in his LA apartment. We had just sat down to watch some basketball when the season was suspended due to Covid-19.

His generosity is well documented. He always picked up the tab. But he did not make a show of it. He simply took care of his friends. All he wanted in return was for his friends to enjoy themselves.

The next night, I Ubered over to Hirshey’s wearing a mask—I have asthma and as a frequent traveler, I’m a bit of a germaphobe; I started with masks on flights in late January. Unmasked, we walked to Gil’s place. When he greeted us and pointed to his trademark pigs-in-a-blanket, arrayed carefully in a circle around a dish of mustard on a small plate, I hesitated … and then went for it. As it was, I stayed away from the communal mustard.

More importantly, Schwartz/Bing had the foresight earlier in the day to visit the dispensary, where he picked up a pack of mini-joints for the pleasure of his guests.

I think of that night as The Last Party. We drank a ton of his good Rye Whiskey. Some, none, or all of us sampled the mini-joints—after all it’s legal here in the “nation-state” of California, as our governor has taken to calling our golden land. As was always the case with our gatherings, I can’t say I remember much of the substance of our conversations that evening. Instead what lingers is a memory of laughter, a feeling of being embraced.

Yesterday morning Fred Schruers sent me a link to this little piece, written by Virginia Heffernan on a New York Times blog more than a decade ago.

As head of communications at CBS, Schwartz’ “colorful and endearing personality” was always on display at annual events like the “upfronts,” where new programming is presented to affiliates and potential advertisers. Heffernan, a seasoned media writer, felt moved to write the following, about the 2007 upfronts:

“Before the CBS presentation begins at Carnegie Hall, I have to say a word about Gil Schwartz. Gil Schwartz has something to do with CBS; his awesome, double-wide, Sopranos-cast face is almost always the first one I see at any CBS event. This time he was pacing around the back corridors of Carnegie Hall, which — like everything secretive and powerful — he seemed to know intimately.

“Gil Schwartz either controls everything in this world or nothing. He writes a business column, or he did. He publishes thrillers under the name Stanley Bing. He kills cobras and possibly journalists. Maybe he even chooses CBS’s primetime lineup.”

In one of two comments displayed online, below the entry, Schwartz writes:

“I prefer to think of my face as “chiseled” not “doublewide”. But thanks for the blurb, Virginia. I laughed.—Gil”

David Hirshey (Stanley Bing’s editor at Esquire and HarperCollins):

Gil Schwartz was so much larger than life that it took more than one personality to contain him. And sometimes even that wasn’t enough. I was lucky to call Gil my friend for four decades and fortunate that I got to work with his not-so-secret doppelganger, Stanley Bing, for most of those years. Bing was the funnier of the two but Gil was the bigger mensch.

Of all the projects I worked on over the years with Bing, which included editing ten of his books, my favorite memories are from the decade we collaborated on Esquire’s Dubious Achievement Awards with several colleagues from the magazine. What I remember most vividly of that time were not his Diet Coke-aspirating one-liners—and there were many. Gil knew a good joke and wasn’t afraid to take credit for it, even when someone else had said the exact same thing five minutes earlier to a smaller laugh.

No, what I remember most is the food. Gil refused to participate in these joke-a-thons on an empty stomach. That meant six weeks of endless lunches, most of them at the Cosmic Coffee Shop on 58th Street and Broadway. In one memorable month, we ran up a $1,400 tab, which, when you consider that the Cheeseburger Deluxe cost about $6.95, is a tribute to Gil’s herculean ability to order food for 19—with just six people the table.

At the 2008 party celebrating “Executricks: How To Retire While Still Working”, Bing is flanked by legendary Ecco publisher and poet Dan Halpern and the author’s partner-in-crime, HarperCollins Executive Editor Dave Hirshey.

Before Gil would flex his humor muscles he also had to be comfortable with the position of our table. He preferred the big one in the corner, next to a young Philip Seymour Hoffman and his fellow struggling actor buddies. “I used to be one of those guys,” he said one day. “I spent two years post-college trying to make ends meet as an improv actor in Boston before I realized it was much easier bullshitting for a living.”

And though I was the editor of Dubious Achievements (meaning I was the guy picking up the tab), the waiters knew who was really in charge. They always treated Gil with great deference, referring to him as Boss Man, probably because unlike the rest of us schlubs, Gil always dressed in a sharp suit that screamed Corporate Macher. Which, of course, he was.

When he arrived at those lunches, he took off his jacket, loosened his tie, rolled up his sleeves, inhaled a plate of sour pickles that had been placed by his seat, and transformed from Gil Schwartz, CBS honcho, into his altered ego, Stanley Bing. The waiters knew his culinary tastes so well they dispensed with menus after the first few lunches. “Chef salad and pound cake for Boss Man,” they’d yell across the room before asking the rest of us for our orders. But then came that fateful day in October 1993 when a waiter leaned over to Gil and said apologetically, “I’m sorry, Boss Man, but we’re out of pound cake today.”

“What else you got?” Gil asked innocently.

“We have a nice piece of chocolate babka,” the waiter replied.

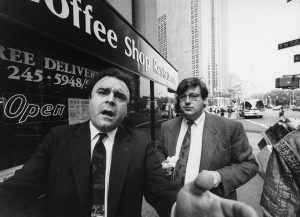

Stanley Bing, outside the Cosmic Coffee Shop, with Michael Hirschorn moments after Bing ingested that “fetid piece of chocolate Babka.” The two men faced off in a celebrated generational battle held in the Hearst auditorium over the relative merits of “Wet” (Bing) vs. “Dry” (Hirschorn) Humor. Bing claimed victory although the judges declared it a draw.

And while it’s never been proven that the cake was sent over by envious executives at ABC and NBC, that “fetid piece of babka”—as it came to be known—was responsible for sending Gil to the ER at Lenox Hill Hospital.

“I recall taking a bite and suddenly feeling ill,” Gil said the next day, fully recovered. “Then I must have blacked out.”

Suddenly, Bing jumped into the conversation. “I may have been unconscious,” he said, “but I still wrote the funniest jokes at the table.”

Michael Solomon (ex-features editor at Esquire, currently with Forbes):

I was very lucky and proud to count both Gil Schwartz and Stanley Bing on my Board of Rabbis for more than 30 years, ever since I was an editorial assistant at Esquire. Bing had nearly infallible career advice—even if he did once warn me “not to become the Walter Isaacson of Hearst.” And Gil was equally full of wisdom when it came life, love and pigs in a blanket.

Above all, he always made me laugh. And he taught me a lot about humor, particularly the difference between what plays on the page and what plays on the stage.

One time at Esquire, when we were working on the Dubious Achievement Awards at our clubhouse, the Cosmic Coffee Shop in midtown, Bing made a joke that cracked up the whole table—we were gasping for air. (I know it was Bing and not Gil because Bing was the funnier of the two.) But I didn’t lift my pen to record the joke when the laughter stopped.

“Why didn’t you write that down?” Bing asked.

“Because it wasn’t funny.”

“Wasn’t funny? What are you talking about?” he snapped. “The whole table just aspirated pound cake from that joke!”

“One second,” I said and transcribed the line he had just regaled us with before handing him the paper.

“You’re right,” he said with a sneer. “It’s not funny. How did you know?”

“Because it only plays on the stage,” I said. “You don’t come with the magazine to do the silly voice and the hand gestures. It’s not funny without you.”

The rabbi smiled because he knew where I had learned the lesson. Then he landed a better joke.

Fred Schruers: (Veteran magazine writer, notably for Rolling Stone. Author of Billy Joel: The Definitive Biography.)

An Aussie friend of mine, newly arrived in the USA, once remarked to me that Americans seemed to have little gift for appreciating irony. Unfortunately for him, and as would be obvious to anyone who spent time in the company of our dearly departed, he had never met Gil Schwartz.

Start with the flabbergasting bifurcation of the man’s two personae. What was represented by Gil’s nom de plume and entire approach as Stanley Bing—an arch, witty slagger of corporate hypocrisy and shallowness—should have been completely at odds with his day job as the top strategist and messaging spinner for the upper-echelon brass of the CBS television network.

One could not always figure out that extreme societal distancing separating Gil and Stanley. That guy who worked all day in a power tie and pricey Italian wool suits in a corner office in the forbidding monolith that was the Black Rock corporate headquarters—what did he share with the guy who whipped that tie off in the parking lot and slid behind the wheel of his lipstick-red muscle car to zoom up the avenues with Nirvana turned up loud?.

As a writer he had a preternatural deftness for working in almost any format. The same consciousness that let him write the avuncular “Ask Gil” column for the eagerly receptive subscribers to Seventeen Magazine was somehow shared with the guy who a couple years back delivered a hilariously sardonic state-of-the biz world address to the massed, appreciative, aging plutocrats of the Bohemian Grove.

Maddeningly, as our pal Dave Hirshey pointed out when quoted in an L.A. Times obituary, Gil wrote many of his columns over the years as a mere fillip to his other tasks on the commuter train. Step on board in New Rochelle and open up a blank screen, by the time the train is passing 125th Street there’s your column—editing optional but hardly needed.

I once told him I was fretting about a featured album review for Rolling Stone and he goes, “Hey, you’ll just sit down to it and write something like, “________________” … and contained in what he spoke then were both informed tendrils showing knowledge of the band in question, and an ever-so-lightly mocking and precise projection of what might be my prose stylings.

He could pick up any stringed instrument and make it talk. Also keyboards. Probably spoons. He held a deep knowledge of blues in particular, and in the month or so leading up to his passing, we had a prolonged back-and-forth mutually appreciating the 1965 Paul Butterfield Blues Band debut album. By that year he had already commenced such side careers as actor, improv comic and playwright, later adding novelist and zealous photographer.

There is no way to way to think about his late-blooming, you-only-live-once efflorescence without recalling an early November trip to Amsterdam Gil staged as impresario of a travel quartet that included Hirshey, fellow writer Roger Director, and me as the Wolf Pack’s Galifianakis. A lovely adventure adamantly financed by Gil alone, organized to a fare-thee-well by the unfailingly sweet, ever-impeccably organized and resourceful wife Laura. Lots of bars, lots of coffee shops, a side trip to the city of Den Bosch where the below photo of Gil was taken, A true dog lover, he befriended a random pooch and through that, the dog’s owner and soon, an entire clan of locals. Bing-a-palooza!

For the smartest guy in the room, he had a truly winning smile.

So, I’ll remember the humor. He was a litterateur who drilled on past the more accessible Dickens and Austen to George Eliot and Thackeray, but there was always a populist streak, throughout the Bing canon. I like to taunt his great friend Hirshey, the majordomo of compiling Dubious Achievements annually at Esquire, that even as an occasional kibitzer Gil had the best one ever. The inciting news item, in the familiar format, stated that researchers at a major American university had determined that one episode of masturbation could kill hundreds of thousands of brain cells. Gil supplied the mic-drop words for the boldface headline above the factoid: “WHO CARE? NOT NEED BRAIN”

It goes without saying he’ll be sorely missed but those who know him best are in general agreement he had a heck of a run and had capped it off in his teen years—that’s 2017, ’18, and ’19—with an admirable and memorable finale. Can’t ask for much more than that in these times.

Jan Cherubin: (Once an editor at Seventeen and style writer at The L.A. Herald Examiner and New York Daily News, now a standup comedian and author of The Orphan’s Daughter, a novel due this summer from The Sager Group.)

I was the editor who gave Gil his first column, “A Boy’s Eye View” at Seventeen. (Was it renamed “Ask Gil” after I left? I guess so.)

Initially, the editor-in-chief of Seventeen (a former nun who’d left the convent after a bout of hysterical blindness) rejected, Gil as my candidate to author the column. She said Gil looked too old in his photo—and that was forty years ago. Gil was never a boy, always a man.

Gil provided an earlier photo and wrote a try-out column. Midge was delighted, and the teen girls went crazy for the 17-year-old kid they didn’t realize was actually a cigar-smoking, poker-playing grown-up.

You wanted to know him and be known by him.

The girls were equally unaware, of course, that in real life Gil referred to the wife of each of his friends, including Roger Director’s wife (me), as “the old ball and chain.”

Why didn’t I resent him for that? I did. We sparred over the years, separated by a kind of social distancing that’s been around a long time—the boy’s club.

When Gil and Laura settled in Santa Monica, just down the hill from us, and mere blocks from Dave Hirshey and Susan Squire, he’d started to mellow (thank you, Laura) and while the boy’s night out lived on (to each boy’s relief), after decades of friendship, Gil and I finally got to know each other for real, and what a gift that was. Gil became my champion, generously and joyfully cheering me on at every standup gig I had in a new career, and casting me in his play reading. He thought I was funny, but I think I earned his respect most just for reinventing myself, like he was able to.

With his untimely death, I feel robbed, of course, as many others do, especially Laura and his kids and his brother. I can’t believe he’s gone. I wanted more time. In a text the day before he died, he asked, for the sake of the other kind of social distancing, that I throw a copy of my new novel over his hedge. I’d like to think Gil, as a media executive, would respect me for the plug.

Frankly, it all feels like a competition—who knew Gil more, who knew Gil first, who saw Gil last. But I guess that’s a tribute. You wanted to know him and be known by him.

Karl Taro Greenfeld: (Another industry vet, Karl is a novelist, journalist and television writer. He is the author of nine books.)

I was at the business end of Gil when I was sent by Time to cover one of numerous CBS-Viacom marriages that served to do little more than continually enrich bankers, M&A attorneys, and Gil’s bosses (and Gil himself, there, I said it, and good for him) but delivered very little value to those who worried that Becker might lose the 9:30 CBS prime time slot. Gil was the flack whose charge I was as he ushered me in and out of various C-suites but he seemed particularly curious as to my own background and history. He also was acquainted with a great many Time Inc higher ups—my own boss Walter, John Huey, Norm, etc.—but I imagined Gil must have done his share of table hopping at the Four Seasons and didn’t think much more about him. I returned to my office and typed up my story and then Walter came downstairs and asked what I thought of Gil. Gil? The PR guy? Who cares about some flack?

The story came back with the usual top edit red and was published and at some point I received a kind note from Gil.

Now, separately, I had a conversation with my editor, Bill Saporito, and mentioned that Fortune seemed like it was going through a particularly good run, and especially this columnist they had, Bing. He was doing something I’d never seen before, writing funny, cynical, acerbic business copy. That’s what I dreamed of doing. And Bill said, “Oh, you know Bing.” And I was like, “Is he on the 23rd floor?”—or whatever floor Fortune was on—and he said, “That’s Gil.” I was like, “Who the fuck is Gil?” And Bill told me he was the CBS flack.

Years later, Gil would claim that he had taken a shine to me at that first meeting, but he was always a generous man, to a fault, even in his opinion of fellow writers. Also, he knew that I would probably be covering the next CBS-Viacom merger and why not flatter me in advance.

I last saw him on New Year’s Eve, when my wife, Silka, and I were the last to leave the party he and Laura hosted and my wife and I were both delighted that Gil, now ensconced in Santa Monica, and his wife, were close enough that we had dinner partners we could both tolerate in striking distance. As my wife usually despises my friends (for good reason) and, well, I have no opinion of her’s, we are often reduced to dining in bitter silence and solitude rather than expose the innocent to our particular strain of discontent. But in Gil and Laura we were looking forward to a few seasons of merriment here and in New York so we were both gutshot for the most selfish of reasons when the news came of his passing: we were losing so many future evenings and good times ahead.

When my wife first met a Gil at the birthday party of a mutual friend, she later asked me what he did, and rather than explain his unique role in the world of letters and because I wanted to get some sleep, I said, “He’s the funniest business writer. Ever.”

[Joining the cadre here is our friend Nathan Jackson. As Hirshey recognized when he signed Nate on to do a well-regarded memoir of life in the NFL (and after), Slow Getting Up, he arrived in our writer cell block with a fully authentic voice and enviable talent.

Right, who wouldn’t resent that? But he was funny and charming and just hanging out with him made us feel younger. Kindly, he invited us to one chapter of his three-days-and-a-cloud-of-dust bachelor party. His lifelong pals were welcoming, and we emerged having agreed to wear the group tag of Old East Coast Fucks. Herewith, his thoughts.]

Nate Jackson:

The first time I met Gil was here in West L.A. at what would become a bro-hang ritual—meet at Hirshey’s or Gil’s for a few brewskis, then go out to dinner with Fred and/or Roger in tow. I was the younger and generationally irrelevant 5th wheel. But they welcomed me like a true Old East Coast Fuck, and I will always be grateful for that. At dinner that night, I was grumbling over the sales figures of my second book. I was telling Gil that I can’t stop watching the numbers, and that it was driving me mad. I knew he was a writer, but I didn’t know that he’d written so much, or so well. Nor did I know that he had done so much other cool shit, either. I would learn this from others, not from Gil. That night, he told me something to the effect of: “No, you can’t do that to yourself. Don’t watch the numbers. Some sell, some don’t. Just move on to the next book. Its a beautiful thing that you have, Nate” he said. “Actors, athletes, they flame out. But you’re a writer, you can do it forever.” This sort of organic advice came effortlessly from Gil, a wise, generous man with nothing to prove.

For a man who had accomplished so much, he never talked about himself. He was more interested in the moment and what joke best suited it, what witticism could best capture David Hirshey’s latest curiosity. The OECFs would often get together to watch sports. Gil was not a sports fan like we are. He tolerated our sports talk but would let us know how silly it was. What Gil did like? Full-bellied banter. He liked a rib-eye at Boa: but not before a wedge salad and a shrimp cocktail. He liked a good whiskey. Rye, not bourbon. Tequila, too. He liked coffee after his meal and he liked a night cap back at his place. He liked to take his time, which put me at ease around him. Whereas Mr. Hirshey would be walking twenty steps ahead trying to get to Ashland Hill to see a certain bartender, Gil would be walking at a leisurely pace, never rushed and never rushing anyone else. Gil seemed to hold time in his hand, erasing the urgency of moving to the next thing, and instead focusing on this thing. This moment. This conversation. Gil looked at you when you were talking and he listened to what you were saying. How else would he land the right joke? Once we left the pre-party and went to whatever restaurant, Gil knew how to have the experience he wanted, because he knew how to talk to people. With his warm eyes and smile fixed on you, he’d ask a question and then listen to what you had to say. That, I will remember most about Gil.

His generosity is well documented. He always picked up the tab. But he did not make a show of it. He simply took care of his friends. All he wanted in return was for his friends to enjoy themselves. But if we ended up going somewhere that David chose; some hipster joint that didn’t have a decent steak on the menu and that made us wait for 40 minutes even though we had a reservation, well, the Uber ride home would be a memorable dust-up of the trusted editor, who might as well have been the man in the kitchen who pre-cut Gil’s hangar steak into tiny slices and arranged it in a flower around a pond of sauce on his plate. Some things were unforgivable.

I will remember more sage advice from Gil—advice about marriage (“just do the dishes”), about fatherhood (“having a baby is like a having a dog, but like, 1,000 times cooler”), about ideas I had regarding helping former NFL players in retirement. He had me as a guest on his podcast to talk about what it means to have a “Game Face”. He hoped for good things for me and my family. As we walked through his backyard to the back house, he told me about his new fascination with birds and told me the names of the different ones he’d spotted feeding in his yard. He told me about his neighbors, about how Laura was so friendly and would talk to everyone and how he was the opposite. He said of all the places he has lived, he felt the most at peace in his Santa Monica house. Hard not to see why—expertly manicured without a false note anywhere. He showed me his many guitars. I suggested a drum set in the corner so we could all jam together. “Now that’s a good idea!”

He and Laura invited me to bring my wife Ariane over for dinner. Ariane had met the rest of the gang but not Gil or Laura, and they wanted to remedy that. This was when Ariane was pregnant. We never did manage to come by for that dinner. We’d planned to come to their New Year’s party a few months ago, but our son Max was born six weeks early on the morning of December 31st. Under the circumstances, Gil excused the absence.

Very recently, he and Laura sent me a generous gift for the birth of my son. And later the same week, he wrote me a thoughtful note about a script I was working on. His only edit was that I had misspelled ‘Phoebe’.

There are more things I remember, but perhaps this is enough for now. I have never met anyone like Gil. I only wish we had more time.

[We give the last word—for now—to Gil’s dear pal, Roger Director, who wrote for magazines like The Real World and Inside Sports in another lifetime. Roger is a novelist and is best recognized for his accomplishments as a television writer and producer.]

Roger Director:

Gil got better every day. And who else can you say that about? Yeah, people talk of two Gils–him and alter-ego Stanley Bing. Those weren’t the two Gils I saw. I didn’t work at CBS with Gil or write anything with him or edit the columns or books he wrote as Stanley Bing. The guy forever doubling ‘Gil’ in my eyes was the guy I first met and was just getting to know over 40 years ago and who had come through risky spinal surgery, who looked up at the doctor as he lay on the operating table and said, “I’m in your hands.” “We’re both in God’s hands” was the reply as Gil started counting backwards from ten.

That’s the little metal hasp at the end of my tape measure for Gil. I start with that. Then Gil got better.

Many were the nights. And places. Over the decades, turning when he turned, walking up a city sidewalk to toss off quips, or turning to get the attention of a waiter or a bartender, or turning to sign a book at his book party, he turned stiffly in my eyes. Some might have seen a guy in mid-life, bulked up by so much success he didn’t crane his neck to see who just walked in. But I viewed his slow turn as the residue of having his body bolted back together after surgery, a metal halo over his head, and who had put that crap behind him, and powered on as if by twin 400 HP Mercs.

From Left to Right: Michael Solomon, David Hirshey, Roger Director, Rob Fleder, Dan Halpern, Richard Ford, Fred Schruers, and Gil Schwartz.

He was as generous to everyone as he was successful. Not nearly or remotely the most recent example: His wife Laura planned and Gil flew three of his friends to Amsterdam late last October. Among my memories— walking through the St. John’s Cathedral in Den Bosch, Gil talking so knowledgeably on the architectural history that Dutch visitors were leaning in to hear.

He and Laura were generous to me personally. To my wife Jan. When my daughter Chloe was stuck in San Francisco just as the city was to go into lockdown in March, Gil and Laura got her out of there and home to us.

They were in Santa Monica by now. And there was a group of us, after all those years, re-sprouted on the other side of the continent minutes apart. And when we got together, in whoever’s house or backyard it was, and Gil was sipping rye or chewing pigs in blankets, it was fun and we ate and drank good and there was a lot of laughter and a lot of back and forth and even a little pushing and shoving and hollering and in the end nothing more you could ask from it.

I was looking forward to becoming even closer to Gil now. The bullshit and the baggage were out of the way and he was living here (mostly) and wasn’t flying in and out on business. I believe he was right with everyone with scant exception when we spoke last. Right for sure with his friends. In synch as always with Laura. Right with his brother Michael. Right with his kids Nina and Will, and his step-kids, Rachel and Kyle.

And right with himself. That’s a lot of what we talked about last Friday afternoon, and when we hung up I said I’d stop by and visit, sit at a safe distance in his front yard and in person.

On Saturday we said Kaddish.