I counted Mike Downey as a friend for 47 years, and the only time he let me down was Wednesday. He had as big a heart as the laws of physiology allowed, a 24-karat, 18-wheeling, let’s-go-to-the-circus thumper that was open to everybody except Kirk Gibson, but Mike let it sneak up from behind and kill him. It rained teardrops when the news reached the multitude of friends and fans he’d made writing sports uproariously, cracking wise memorably and living life beyond his wildest imaginings. I can only hope that something funny had just occurred to him when checkout arrived.

It was on our first road trip together—Final Four, St. Louis, 1978—that I was introduced to the essential Downey. He stayed up all night watching a local TV station and somehow found inspiration in a comedy troupe that was booked at an hour usually reserved for burglars and milkmen. The highlight of their routine, if highlight is the right word, was a goofy debate about farm animals.

“M.R. pigs,” one goober said.

“M.R. not,” the other goober said.

“O.S.A.R.”

“No, no, M.R. not.”

And so on and so forth. Mike told me all about it in the morning. For the rest of the tournament, that was how representatives of the Chicago Sun-Times communicated. Mercifully, we stopped when the tournament ended. But every once in a while decades later, Mike would get a gleam in his eye and say, apropos of nothing, “M.R. pigs.” It sounded even goofier when you realized it was coming from one of the nation’s leading sports columnists and the proud husband of Dean Martin’s daughter Gail. If you’re wondering if Mike ever met Dean, the answer is no. But he did call him “Dad.” It always got a laugh.

Mike’s instinct for comedy was cultivated in an unfunny place, a blue-collar suburb southwest of Chicago where people learned to laugh because their only option was crying. He never talked about it much, but in his short, unhappy turn as a general interest columnist at the L.A. Times he did write one column about a family Christmas that would have made Dickens weep. It was beautiful and I told him so. But he didn’t want to hear it, and he never returned to the subject. He just knew that he wanted to get out of Harvey, Illinois.

The only escape plan he had involved professional wrestling. His towering buddy Terry Boers would be a creature who rose from a coffin before every match and Mike would be his manager. Good thing there was a highly respected weekly in the area that would hire him when he was fourteen and mold into the best all-around newspaperman I ever met.

In 1977, when I arrived at the Chicago Daily News to write a sports column, Mike was part of the lean crew that worked all night to put out the sports section. It was obvious he was a wizard. He could pump life into a story that was seemingly dead on arrival. He could lay out a handsome page and crop photos in ways you never would have imagined. Best of all, as far as I was concerned, he wrote the most consistently memorable headlines that ever adorned my prose. When I defended the beleaguered Olympic star Dorothy Hamill, Mike delivered a work of art: “She’s Dorothy, Not the Wicked Witch.” In six words, he said more than I did in the thousand that appeared beneath the headline.

Elmore Leonard, the great crime novelist, name-checked Mike in one of his bestsellers, Be Cool.

He went one step further, however, the night he refused to let the presses run before my column about a raucous NBA playoff game arrived from Philadelphia. He wasn’t a tough guy or a brawler. I’m not sure I ever heard him swear. But he stood his ground against the back-shop guys—tough, fractious, ink-spattered—and they backed down. Only later did I realize that Mike would have stood his ground for any writer on the staff.

Not long afterward, assignments got shuffled and he became one of us.. He put his stamp on basketball, pro and college, with movie trivia, pop culture odds and ends, and a sense of humor that owed as much to Redd Foxx as it did to Red Auerbach. It was clear there was a columnist inside him rattling the cage in which beat work trapped him.

The narrative from that point on seems to be common knowledge. His first gig as a columnist was at the Detroit Free Press where he was, quite simply, adored. Elmore Leonard, the great crime novelist, name-checked Mike in one of his bestsellers, Be Cool. Then Mike headed for L.A. and a long, mostly happy run at the Times, first as the legendary Jim Murray’s wingman and finally as the lead columnist on a stunningly talented staff that included Rick Reilly and Richard Hoffer. Of equal import to long suffering scribes, he wouldn’t let Tommy Lasorda broker a peace agreement between him and Kirk Gibson, the Dodgers’ crass, sexist hero. Mike refused to speak to him.

When enough was enough, he tried retirement, then bobbed back to the surface at the Chicago Tribune. It seemed like an appropriate finish line for an almost native son, but Chi-town, for all its virtues, was still Ring Lardner’s town. When Mike moved back to L.A., he left no footprints behind.

By then it didn’t matter. He knew who he was and what he had accomplished. All his family and friends asked was that he remain the Mike they loved whether he was writing sports or not. He remembered birthdays and sent notes written in a hand both manly and elegant. He gave gifts that always seemed perfect for the recipient. And when I became a regular at some of L.A.’s finest doctors’ offices and emergency rooms, he ferried me around town without a word of complaint. (Of course, he and Gail did eventually move to Rancho Mirage.)

One day we looked around and realized we had become old men. It was the same day we could only make it halflway across Wilshire Boulevard before the light changed. Mike’s bum knee was torturing him. Every step I took felt like I was walking in wet concrete. The only pleasant thing I remember about that afternoon is our conversation about a cool but forgotten little movie called Things to Do in Denver When You’re Dead. Near the end of it, with cruel fate about to clamp them in its steel jaws, Andy Garcia visisits his old partner in crime, Christopher Lloyd. Garcia really has only one thing to say, and he wants to say it when he’s looking Lloyd in the eye: “Boat drinks.” It’s the toast they share when circumstances are about to take them in different directions. Two small-time wise guys wishing for a future with tall, cool libations rimmed by fruit slices and maybe a tiny parasol.

Mike and I jumped on that one like it was a fumble. In the beginning, it was something to laugh about, but after he retreated to the desert, the toast took on more importance. I still wanted to hear about his grandson starring as a high school hurdler, and my heart soared when I learned that Gail’s youngest daughter had given birth to a daughter of her own. Gail had made it through a year of surgery and pain and Mike’s 73rd birthday would roll around in less than a month. Life was mellow. Then someone called with the news and there was only one thing I could say. It would be for the last time.

Boat drinks, Mike.

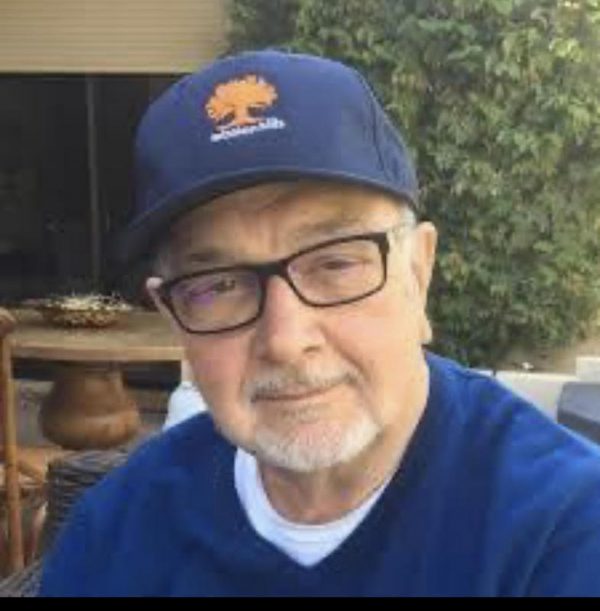

[Photo Credit: Mike Lagaan via Wiki Media Commons; and Gail Downey]