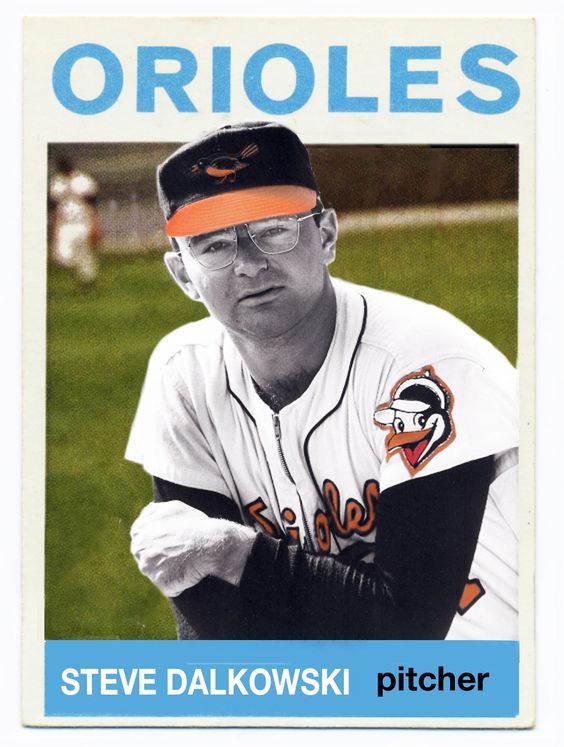

It was a groundskeeper in Stockton who first told me about Steve Dalkowski, the fastest pitcher of all time. Dalko once threw the ball through the wooden boards of the right-field fence, he said. The groundskeeper studied the broken boards, maintained like a shrine, and the Dalkowski stories started flowing. In minor league ballparks all over the country, they still talk about the hardest thrower of them all.

He’s not big, they always say. Little guy, glasses, doesn’t say much. Just to look at him you’d never guess who he was, but then most people never heard of him anyway. A cop in Bakersfield still keeps an eye on him, makes sure his rent is paid, picks him out of the gutter. His arrest record is fourteen feet long, the cop says, all drunk and disorderly. A bar in Oildale, another fight with some unemployed oil rigger, a fight about nothing, about everything.

The cop says, “Don’t try to be a hero, don’t try to help him, he’s gettin’ by. Some woman fell for him again, is trying to clean him up. It won’t work, never has, every five years some decent broad tries to clean him up. Fails. Leave it to the broads. Nothin’ can be done.”

Summer nights in Bakersfield he can still be found, standing in the oven heat down the right-field line near the bullpen, watching the minor leaguer pitchers loosen up. Every few years a sportswriter from the East flies in to do a piece about him for a big magazine, but the little guy never shows up for the interview. Except for that, and the cops and the groundskeepers, nobody knows who he is.

To the ballplayers in the bullpen he’s just another drunk. It matters not that he used to pitch in that very ballpark, that he used to be the greatest pitching prospect of all time. From a prospect to a suspect, they used to say. And if you don’t believe the groundskeepers and the cops, ask the veterans.

The fastest pitcher I ever saw? Easy. Dalkowski. Dalko, we used to call him. Little guy, glasses. Drank like a fish. Had unbelievable heat. Blew it by Ted Williams in spring training. “Fastest ever,” Ted said. “I never want to face him again.” Harry “The Cat” Brecheen called it “the best arm in the history of baseball.” Cal Ripken Sr., his catcher in the minors said, “Nobody else was close.” And the stories are endless.

If the stories can be challenged, the numbers can’t. In the end, that’s what baseball reduces to after all—stories and numbers. That’s what’s wonderful and terrifying about the game.

In the days before radar guns, the Baltimore organization sent him out to the Aberdeen Proving Grounds the night after throwing a complete game. They set up a tube-like device on a tripod above home plate that could measure the speed of an object in flight. The problem was, of course, Dalko couldn’t hit the damn thing. He threw for forty minutes before sneaking a fastball down the tube: 98.6 miles an hour—without a mound. A fresh, sober Bob Feller threw 5 miles an hour slower through the same machine. Some say Dalko would’ve stopped a radar gun at 120 mph.

In Wilson, North Carolina, he threw a wild pitch through the welded mesh screen sixty feet behind the catcher. Thirty years later the hole in the screen is still there.

He stood in front of the center-field clubhouse in Stockton, 430 feet from home plate, watching his teammates place bets to see if any of them could throw a ball to home plate on a single bounce. One of them did. His curiosity aroused, Dalko picked up a ball. Without warming up, still in street clothes, he threw it over home plate. Over the backstop. It landed in the press box somewhere.

There was the time his catcher couldn’t get the glove up fast enough and a rising fastball hit the umpire in the mask, shattering it in three places. The ump got off easy, people say, compared to the guy who had his ear ripped off by one of Dalk’s 0-and-2 pitches. It was a clean tear, they said. Sewed back on real easy.

They sent him to Florida to play under the steady influence of a veteran manager and just maybe, shake his love of drinking and partying. They wanted to him to mature. Instead, he became pals with Bo Belinksy. The manager had a heart attack.

And if the stories can be challenged, the numbers can’t. In the end, that’s what baseball reduces to after all—stories and numbers. That’s what’s wonderful and terrifying about the game. A broken bat hit looks like a line drive in the box score. And a line drive to short is just another 0 for 1. In the history of professional baseball, there are no numbers like Dalko’s.

In a nine-year career, he averaged 13 strikeouts for every 9 innings. He also averaged 13 walks.

He struck out 262 in 170 innings in Stockton in 1960. He walked 262 the same year.

He threw 283 pitches in a complete game at Aberdeen one night, but a few days later 120 pitches only got him out of the second inning.

There was the game he walked 21, struck out 18, and threw a no-hitter.

The Appalachian League, the South Atlantic League, the Carolina League, the Northern League … nine leagues in nine years. Every league but the one that matters. With the best minds in baseball trying to teach him control. Paul Richards, Earl Weaver, Billy DeMars, Harry Dunlop—these were the great Oriole years when a baseball empire was built on fundamentals—none of them could help Dalko get the ball over the plate.

And then, in ’63, something happened in Elmira. Suddenly Dalko was throwing strikes. His strikeout numbers stayed high, his base on balls dropped dramatically. He changed, they said, maybe because he’d met a woman. More likely because he hadn’t. Koufax had been wild in his early years until, magically almost, he took a little off the ball and began throwing strikes. Koufax had been letting up? It’s a frightening thought, but maybe that’s what Dalko needed. Tame the thunderbolt—it’s still a thunderbolt. His ERA dropped under three—there were years it had been over twelve—and he started winning.

Dalko went to spring training with the Orioles where the big leaguers gathered around the cage to see firsthand the arm they’d been hearing about. That’s where he blew it past Ted Williams. Where he struck out the side in two appearances. His wander in the wilderness was going to be worth it. Dalko would be the greatest short reliever in history—come in with the bases loaded and throw 120 mph strikes to close out the game. All the bus rides and drunken binges and seasons in mildewed motels in places like Pensacola, Stockton, Kennewick, were leading to New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, after all ….

Jim Bouton was the batter, of all people, in the spring training game. There was a runner on first when Bouton laid down a sacrifice bunt. Dalko jumped on the bunt, whirled, threw to first. And his arm went dead. It was nothing dramatic, nobody even knew at first. Bouton barely remembers the moment, but the indestructible left arm of Steve Dalkowski, abused, alcohol sodden, able to throw baseballs through wooden fences—was gone like that. Zeus quietly took back his thunderbolt, and Dalko returned to the minors to wander around for a couple more years.

He threw his last pitch in the Mexican leagues, drifted back to Stockton, got married, divorced, and lost a dozen jobs. A bartender, a forklift driver, a ditchdigger—he even worked in his mother-in-law’s pet shop, but he couldn’t hold that job either. Up and down Highway 99 in the San Joaquin Valley, another marriage, another divorce, a couple kids along the way, hitting all the bars in all the farm towns, he found at last one job that required neither a resume nor a reference. Dalko began picking cotton in the towns where he once pitched.

Twenty years later, he’s still standing down the right-field line in Bakersfield, still watching the games, still drinking. On this night the woman finds him and takes him home. Or maybe it’s the cop. In either case it’s a night he won’t end up in jail.

At dawn, he’s in the back of a truck filled with Mexican farmworkers. He rides silently to the fields. Certainly he’s the only Polish grape picker in Kern County, the only migrant farmworker from New Britain, Connecticut, and the only man on that truck who ever terrified Ted Williams.

And whether the gift of his left arm was an act of grace or just a cruel trick, and whether or not any strong woman ever dries him out, and whether he lives out his life in peace or shows up some morning in the Bakersfield morgue—just another drunken brawl—he takes something to the fields of Delano no one else can claim.

Dalko, the little guy with glasses, the guy who drank like a fish, was the hardest thrower of them all. It’s in the numbers and it’s in the stories. And in baseball, at least, that’s enough.

[Ron Shelton played professional baseball in the Baltimore Orioles system and later wrote and directed Bull Durham, Cobb, White Men Can’t Jump, and Tin Cup—to name just a few. He also wrote one of our favs, Under Fire.]

[Photo Credit: Joel Sternfeld c/o The Art Institute of Chicago; Cards That Never Were via Pinterest]