Twenty-four years ago, when I was a college junior with vague literary ambitions, a friend of mine and I were rummaging through a bookshop near the downtown campus of Chicago’s Loyola University. Weary of required readings—Milton, Pope, the Victorians—we were on the lookout for something too fresh and modern to have yet found its way into an undergraduate curriculum. At some point during our browsing, my classmate pulled two paperbacks from the shelf and said, “You’ve got to read this guy. He’s terrific.” The books were William Styron’s Lie Down in Darkness and The Long March.

On my friend’s recommendation, I bought both, but I read The Long March first because it told the story of a Marine rifle company driven to the limits of endurance on a stateside training hike during the Korean War. (I had joined the Platoon Leaders Class, the Marine Corps’s version of ROTC. ) Styron served in the Marines in World War II and the Korean conflict, and the authenticity of the book impressed me.

Lie Down in Darkness sat on my shelf unread for some time. The flyleaf blurb said it was about a doomed young southern girl. As I was in an ultra-macho period of my life—soon to be commissioned a Marine officer, and an amateur boxer and college wrestler who was also a voracious reader of Hemingway and Jack London—I had no interest in doomed young southern girls, fictional or otherwise. I eventually decided to give the novel a try. Beginning it was the equivalent of launching a rubber raft into the faster reaches of the Columbia River; it swept me away from the moment I read its wonderful first sentence:

Riding down to Port Warwick from Richmond, the train begins to pick up speed on the outskirts of the city, past the tobacco factories with their ever-present haze of acrid, sweetish dust and past the rows of uniformly brown clapboard houses which stretch down the hilly streets for miles, it seems, the hundreds of rooftops all reflecting the pale light of dawn; past the suburban roads still sluggish and sleepy with early morning traffic, and rattling swiftly now over the bridge which separates the last two hills where in the valley below you can see the James River winding beneath its acid-green crust of scum out beside the chemical plants and more rows of clapboard houses and into the woods beyond.

By the time I’d read the final sentence, my disinterest in doomed young southern girls had vanished; the magic of Styron’s prose had passionately involved me in the fate of his suicidal heroine, Peyton Loftis. I was a fan. I was also deeply discouraged as far as my own ambitions went. Its carefully crafted prose, intricate structure, and brilliantly realized characters made Lie Down in Darkness sound like the work of a forty-year-old master. It stunned me to learn that Styron had begun it at twenty-two—only two years older than I was at the time—and had been a mere twenty-six when he’d published it in 1951 to rave reviews and won the Prix de Rome of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. I took a gloomy inventory of my own efforts and strongly suspected that I had about as much chance of writing another Lie Down in Darkness at twenty-two as I did of hitting baseballs like Ted Williams or throwing a left jab like an upcoming heavyweight then named Cassius Clay. I was sustained only by the hope that, with a lot of hard work, I might someday measure up to the standard Styron had set.

I read his third novel, Set This House on Fire (1960), and then discovered that being a Styron fan required patience: The Confessions of Nat Turner did not appear until 1967, Sophie’s Choice until 1979. A few years passed, during which Styron published a collection of essays entitled This Quiet Dust, but no fiction. I’d begun to wonder if he’d gone into retirement; then, in the early spring of 1985, I learned that Styron was working on a new book, The Way of the Warrior, a big war novel set in the South Pacific in 1945. A few weeks later, a magazine asked if I would accept an assignment to interview him about the book and also obtain his views on the craft of writing, his career, his work habits, et cetera. I accepted without hesitation because, frankly. I wanted to meet the man.

Styron was months away from a breakdown that would so alter his vision of the novel he would have to begin anew.

The assignment led me to reread Lie Down in Darkness. My intention was to skim it to refresh my memory. I was now middle-aged, with a modest literary reputation of my own, one that had been enhanced by the favorable review Styron himself had given my first book, A Rumor of War, in The New York Review of Books. So I assumed the novel would not have the overwhelming effect it had had on me in my youth. But it did. Rather than skim it, I devoured it. When I came to the end and heard once more the funeral train that had borne Peyton Loftis’s body back to her hometown, heard it clattering “toward Richmond, the North, the oncoming night,” I did not, as I had more than two decades earlier, suspect I was incapable of writing such a novel. I knew it.

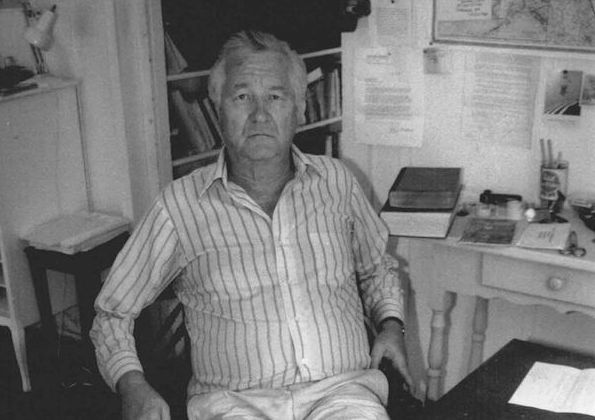

So when I arrived at Styron’s house in Roxbury, Connecticut, on the first day of the 1985 Memorial Day weekend, I’d half expected to find him as formidable as his work, a kind of éminence grise. That did not turn out to be the case. I met him late in the afternoon, after Rose, his gracious and energetic wife, had shown me my room and what was where in the 130-year-old house, a rambling place where you do not feel uncomfortable kicking off your shoes and putting up your feet. Heavyset and moderately tall, with a head of straight gray hair, Styron appeared to me to be a man who could have played the éminence grise if he’d worked at it; but I suspected that the merriment in his brown eyes and the smile on his thin lips, a smile that hovered in some borderland between the genial and the ironic, would have undercut any attempts on his part to appear imposing. His dress was casual—a shirt unbuttoned to the chest, old slacks, deck shoes—and his manner appeared relaxed, an appearance that was to prove deceptive. We hit it off fairly well, drawn to each other by our service in the Marines, that mystical, martial brotherhood. Styron invited me to interview him about the new book while he took his daily five-mile hike. I accepted; it seemed appropriate for two ex-leathernecks to discuss a war novel while tramping down an unpaved road.

Outside, he called to Aquinnah, the retriever that accompanies him on his walks, a handsome animal that he cryptically described as his “only friend.” The dog came bounding up the broad lawn and hopped into its master’s Mercedes—one of the symbols of the considerable (by literary standards) financial success Styron has achieved. We then drove a short distance down an asphalt road, parked at its junction with a gravel one, and set off on foot through the low, wooded hills of southern New England, Aquinnah ranging out ahead. Styron, a sedentary man who prefers to sleep late, said his daily “long march” was his sole form of exercise, its purpose to keep his thickening midsection down to respectable proportions, his arteries flowing freely.

“A doctor told me that a walk like this pumps a completely fresh supply of blood through the heart,” he said, setting a faster pace than I’d expected from a man approaching his sixtieth birthday (he was born June 11, 1925).

He then began to give me a sketch of The Way of the Warrior. He was guarded, for, like most writers, he is wary about discussing a work in progress. As matters were to turn out, Styron could have talked the book to death; on that pleasant spring afternoon more than a year ago, he was only months away from a nervous breakdown that would send him into a hospital and so alter his vision of the novel that he would throw most of it away and have to begin anew.

As he outlined it for me during our walk, The Way of the Warrior was to be a historical novel, set in the final days of World War II, with flashbacks to the Great Depression. The story would have been told by the same Stingo who had narrated Sophie’s Choice. A sensitive, libidinous young writer in that novel, Stingo was to appear in The Way of the Warrior as a Marine platoon leader, eager for action and “appallingly fit” … with the rib cage of a “slightly underfed young panther,” as Styron described him in an excerpt of the novel that appeared in Esquire’s 1985 summer-reading issue. Stingo’s best friend, Lieutenant Douglas Stiles, an articulate, fire-eating fanatic, was to be the central character. Stiles’s zeal to fight the Japanese, in Styron’s original scheme, was partly motivated by the conviction that they had to be quickly defeated so the U.S. could battle the Soviet and Chinese Communists, the greater menace, in Stiles’s view. The action was to be centered on the battle for Okinawa, the prelude to the planned invasion of Japan, which was averted when the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended the war.

“That’s part of the novel, too,” Styron told me. “The bomb is very much involved in the story in the sense that it prevents Stingo from going to Japan. By this time, the kid is so fed up he doesn’t want to go.”

Styron’s pursuit of the grand makes him a marvelous anachronism among today’s American writers.

I remarked that the Stingo in Sophie’s Choice felt quite differently about his military experiences than the Stingo in The Way of the Warrior: “I had, in bitter truth, heard not a shot fired in anger,” Stingo reminisced in the first chapter. “I could never get over the feeling that I had been deprived of something terrible and magnificent.”

Despite service in two wars, Styron himself never heard a shot fired in anger; he was saved, like his fictional alter ego, from the crucible of combat in Japan by the dropping of the atom bomb. Recalled to active duty for the Korean War, he once again escaped seeing action; after serving nine months in the States, Styron was medically discharged for an eye defect.

I mentioned that Hemingway, among others, had said that a taste of battle benefited a writer, a statement with which I only partially agreed. Certainly, America’s wars have launched a number of writing careers—Vietnam appears to have produced a literary school of its own. On the other hand, combat can sear a man’s emotions so deeply, can so obsess his thoughts and imagination that he often finds it difficult to write well about anything else. Did Styron feel he had been “deprived of something terrible and magnificent,” or spared an experience that might ultimately have crippled his talent? Could he have written Lie Down in Darkness had he heard that shot fired in anger?

We had by this time come to the end of the gravel and were heading down the shoulder of the asphalt back toward the car, Styron frowning as he reflected on the question.

“I got close enough to know that I didn’t want any more, you know what I mean?” he answered after several moments. “And probably not having had that ultimate crucible happen to me left me free to be preoccupied with other things.”

The weekend was crowded with visiting family and friends, dinner parties, and a holiday picnic at a secluded woodland pond that could have been straight out of Thoreau. For some reason, Styron made a point of telling me that he normally does not lead so busy a social life; indeed, he appeared to be a little uneasy in large groups and seemed most comfortable talking one on one, either in his living room or out on the patio, sipping a drink and savoring a cigar.

His conversation tended to be almost as political as it was literary. Rather frequently, he spoke about what he called America’s “anticommunist paranoia,” a theme that was to have been personified in the character of Lieutenant Stiles. Styron talked at length about his distress over the Reagan administration and the country’s rightward march. His concern with issues somewhat surprised me; I’d always thought of him as a writer’s writer, a “pure” artist, if you will. I had begun to wonder if, in The Way of the Warrior, he had become engagé, marrying art to politics. That union is an old and respected one in Europe but is looked upon as vaguely illicit in America, the corruption of art into polemic. Styron assured me that he was writing the novel for the same reason he had written Lie Down in Darkness: the joy of creation, the joy that arises from the fulfillment of a need to “grasp something of the nature of existence” and set it down on paper.

Nevertheless, he added, “I am amazed in retrospect that I am as political as I am, given the fact that I began as a writer who was totally ivory-tower oriented. Lie Down in Darkness is a book of very little political sensibility…. My statement is not regretful, but I guess I have, over the years, almost unconsciously let my work be connected with politics, with politics insofar as they govern history and human affairs.”

By “ivory tower,” Styron explained, he meant that he’d “believed that if you read T.S. Eliot, that was all you had to do to get through life, and if I wrote a novel illustrated by Aubrey Beardsley, it would be just wonderful. I thought of literature as just pure literature in my early days.”

The event that wrenched him out of this rarefied world, he said, had been his recall to active service at the outset of the Korean War.

“It was traumatic to me to be exposed, once again, to that military thumb. Going down to Camp Lejeune [the North Carolina Marine base that is the setting for The Long March] to fight, eventually, a bunch of Chinese because they were communist, in a miserable Oriental peninsula about which I knew nothing, for no discernible ideological reason.”

But the experience was not without value to him as an artist: it taught him important lessons about how the authoritarian mind works, he said, and those lessons served “as an adjunct to what I’ve been writing about all my life, which is, I think, involved with the way human beings dominate each other.”

Prying into a writer’s life, Styron said, is “trivial, a degrading pastime that is best left to gossip columnists.”

Although Styron points to the Korean War as the seminal event in “politicizing” him, the roots of the social and political consciousness that inform his later work can be traced to his upbringing in Newport News, Virginia, during the Depression. His father, William Sr., a cost engineer in a shipbuilding yard, was an old-fashioned populist who had a hatred of monopoly capitalism. His mother, Pauline (who died when he was thirteen), was “a woman of high principles … a Christian without being pious … she believed in good works and she was a big worker for human rights.’’ Styron’s direct connection, through his paternal grandparents, to the Civil War gave him an early interest in slavery and racial injustice. His grandfather, Alpheus Whitehurst Styron, fought for the Confederacy and was wounded in a skirmish near Goldsboro, North Carolina. His grandmother, Marianna Clark, came from a slave-owning family and, when Styron was a boy, told him stories about the two black girls who had been her personal handmaidens.

“It always amazed me that I had that direct link, that these were not great-grandparents, but grandparents, that my link was that close to slavery.”

That sense of amazement eventually moved Styron to write his novel about Nat Turner, accounts of whose slave rebellion he had read while a student at Duke University.

Growing up in the Depression South, Styron did not have to look into the distant past to find the more repulsive aspects of racism. He saw them every day in the streets of Newport News, an industrial city as distant in atmosphere as it was in miles from Faulkner’s rural Mississippi. The city had a dense black population whose hopeless poverty outraged the young Styron, awakening in him a painful awareness of “the disparity between what was preached to me about justice and human rights at home and what I saw.”

In the meantime, he had begun to write, encouraged by his parents’ love of literature. The mere presence of books in the house, he said, had validated the act of writing. His first story, published in the school newspaper when he was twelve, was a “shameless imitation” of Joseph Conrad entitled “Typhoon and the Tor Bay.” He continued his efforts throughout high school and at Duke, which he attended for two years before entering the Marine Corps. After his discharge and a brief adventure in the Merchant Marine delivering cattle to postwar Trieste, he completed his studies at Duke, then headed for New York with the seed of a novel in his head.

Styron did a stint at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, where he learned nothing about his chosen craft, then went on to the New School, where he did, studying under Hiram Haydn. Although he considers most writing schools to be “nothing more than lonely hearts clubs for like-minded people to get together,” he has credited Haydn as an important influence on his early career, along with William Blackburn, who taught him at Duke.

Supporting himself with a small inheritance from his grandmother and an editor’s job at McGraw-Hill, Styron began Lie Down in Darkness in 1947.

Its setting, Port Warwick, Virginia, was an imaginative rendering of Newport News, but the novel had nothing to do with the social and racial inequities there. Its inspiration lay in the story of a hometown young woman who had fallen in love with a married man, a handsome golf pro.

“And he did her wrong, as they said in those days. So this girl, in an excess of anguish over being jilted or whatever happened, drove seventy miles an hour right off the Old Point Comfort shipping dock. The description of the car and her screams as she flew through the air before hitting the water just haunted me.”

He found in the vulnerability of a doomed and beautiful young woman an appeal to “one’s sense of the nature of tragedy…. It seemed to me a terrible commentary on the human condition.”

In Lie Down in Darkness, the young beauty who drove her car off the dock becomes Peyton Loftis, who leaves Port Warwick for New York, where, after a failed love affair, she commits suicide by leaping out a window. It is a novel about private life, in contrast to Styron’s later works, and in that sense belongs to the grand tradition of Tess of the D’Urbervilles, Madame Bovary, and Anna Karenina. In another sense, it is a quintessential American book. In Hardy, Flaubert, and Tolstoy, society is the rock against which people fling themselves, break, and bleed. But unlike Tess or Anna, Peyton, a modern American girl, can run away from the conventions of society. She can and does; but she cannot escape the self-destructiveness in her own heart, an ugly inheritance bequeathed by her father, Milton, a dissolute, philandering lawyer who spoiled her, and her mother, Helen, one of the more memorable bitches in contemporary American literature.

Madame Bovary and Anna Karenina were major influences on Styron when he was working on the novel. Both, he said, were “works of deep humanity,” and, resolved to write a mature book “by avoiding the trap of most young writers to participate in emotion themselves,” he sought to emulate Flaubert’s emotional detachment.

“It was an act of rigorous, willed detachment,” he went on, “maintaining an emotional distance while describing emotional situations…. I was determined not to be a ‘young’ first novelist.”

The struggle to achieve that, he recalled, had not been a strain, but a pleasant effort. A more difficult battle, one shared by almost all southern writers of his generation, was getting out from under the enormous shadow cast by William Faulkner—the “Dixie Special,” in Flannery O’Connor’s memorable phrase.

Assessing Lie Down in Darkness, Styron said he did not think he had been completely successful in ridding himself of Faulkner’s influence; still, he had been successful enough to claim he’d written a book in his own voice.

“You can’t spend your life living with a monument. If you’re going to be a writer, you become a writer on your own terms and totally set yourself free from that influence.”

The novel established him as one of the heirs to the southern tradition. After its publication, however, he divorced himself from that tradition in the geographical as well as the artistic sense. In 1957, after sojourns in New York and Italy, he and Rose moved to Roxbury and have lived there ever since. He became not a southern writer, but a writer who came from the South.

Styron’s account of what he called his journey to the edge of the abyss was almost supernaturally frightening.

“You go North, “ says one of the characters in Lie Down in Darkness. “You become expatriated, exiled … yearning to repudiate the wrong you’ve grown up with….” Had that been Styron’s motive in adopting New England as his home? Or had he discovered that he could not totally liberate himself from the Faulkner legacy while remaining in his native region?

He answered both questions with a shake of his head. “I wasn’t rebelling in any sense. I just found intellectual life up here more congenial.”

However intellectually congenial New England may be, Styron paid a price for his self-imposed exile from the South: “I think I have sensed a lack of a milieu of the kind Faulkner had in Mississippi, with this extraordinary material to draw upon.”

Indeed, Lie Down in Darkness aside, there is no equivalent in Styron’s works of Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County or Thomas Wolfe’s Asheville, North Carolina—no sense of place. Nor is there a definite thematic thread running through his novels. True, the theme of tragic women has dominated two of his books, and there is a superficial connection in military subject matter between The Long March and The Way of the Warrior. By and large, though, no one of his novels can be singled out and described as vintage Styron: each seems to have been written by a different author, the styles varying from the lyricism of Lie Down in Darkness to the taut, angry prose of The Long March and Stingo’s conversational narration in Sophie’s Choice.

In Styron’s own words, his lack of a milieu forced him to “cast around for themes, there’s no doubt about that.”

But there is also no doubt that he goes after the big fish when he casts his net. Perhaps net is the wrong word; harpoon would be more like it, because the themes he hunts are of Moby Dick dimensions—black slavery, the Holocaust, and, in The Way of the Warrior, World War II, the Bomb, and the Cold War. This pursuit of the grand makes Styron a marvelous anachronism in a period when many younger American writers are turning out literary equivalents of the microchip: tidy, polished short stories and novellas dealing with small domestic dramas, and peopled by isolated, introspective characters.

Styron, describing The Confessions of Nat Turner and Sophie’s Choice as historical novels, attributed his attraction to big themes to his conviction that history is a “marvelous and clear mirror” of human behavior.

“There is such chaos in contemporary events that you need the historical perspective to put things in focus. The use of history gives you a view of human nature that is often more accurate than the one you get when dealing with matters in the present.”

His use of the broad canvas partly accounts for the impact that most of his books have had in critical as well as commercial terms. His last two novels became literary events and stirred no small amount of political controversy. When The Confessions of Nat Turner appeared in the mid-1960s, at the height of the civil rights movement, it was praised by some critics and damned by blacks and the radical left, whose relentless pounding of the book caused Styron “deep unhappiness.” And it was plain to me that he still felt the wounds, probably because attacks continued to be made against the book years after its publication.

The two most frequent accusations have been that a white southerner cannot write honestly about a black slave and that Styron distorted a historical figure, a black hero, by making him lust for Margaret Whitehead, the novel’s flirtatious white heroine.

Commenting on the second charge, Styron cited the opening chapter of Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice, “which is nothing but a hymn to the love of white women, the almost obsessive love and lust on the part of black men for white women.” That, he said, vindicated his portrayal of Nat. He characterized the first criticism as unjustifiably proprietary. Exclusive claims by ethnic, religious, or racial groups to certain subject matter are, in his opinion, ultimately detrimental to literature and freedom of expression.

“It makes everyone self-conscious about racial issues to the degree that one becomes, as a writer, ridiculously fastidious when dealing with gut race issues—Many black women writers seem to have a terrific hatred of the book. One of them was quoted in The New York Times last summer [1984]…. She used Nat Turner as an example of a novel that she tried to read but couldn’t finish because of its racism, exposing herself in the process as a person who is utterly bigoted in terms of the book.”

After the bombardment Nat Turner received from blacks, Styron was pleasantly surprised when Sophie’s Choice did not suffer as severe an assault from Jews. The film version, however, did not escape entirely unscathed. Among other things, it was criticized for its humanizing of Nazi concentration-camp officers and the steamy sex scenes between Sophie and her German lover. Elie Wiesel, reviewing the movie in The New York Times, echoed black criticisms of Nat Turner by stating that Styron did not have a right to use the Holocaust as subject matter because it was an event so awesome that it was beyond the power of language to convey.

Styron, echoing his response to Nat Turner’s critics, said that it was “nonsense” to declare the Holocaust out of literary bounds.

“It is certainly an experience that requires far more tact, honesty, and delicacy, but I have never understood any logic in the statements that it cannot be dealt with by a writer or an artist, and if it is dealt with, it certainly cannot be by someone who was not there, who was not a survivor.”

As for his humanizing of the Nazis, Styron pointed out that they were neither demons nor extraterrestrials; they were ordinary men who committed extraordinary, indeed monumental, acts of barbarism. Their monstrosities arose from hearts undeniably human.

A white Virginian who delved into the mind and soul of a black slave, an Anglo-Saxon Protestant who described the Holocaust through the eyes of a Polish Catholic woman, a New Deal liberal who is, in the age of Reaganism, writing a novel that suggests our anticommunist policies are a form of national paranoia, Styron assuredly cannot be faulted for avoiding the difficult. I was struck by the contrast between the controversial, often violent nature of his writing and his genteel country-squire style of life. He had the air of a man quietly confident of his talent and his place in American letters. When, noting that he’d published only five works of fiction in thirty-five years, I asked if he had ever feared during the long intervals between books that he would be forgotten by the reading public, he tersely answered, “No.”

The self-assurance suggested by this one-word reply may have been unintentionally deceptive; for Styron, as I would soon learn, was full of doubts even then about himself and his new book, doubts that would contribute to his collapse into acute depression within a matter of months.

The Confessions of Nat Turner, which won the Pulitzer Prize, and Sophie’s Choice, which won the American Book Award, each spent almost a year on the best-seller lists. The film rights to the former sold for an astonishing $800,000 in 1968, while the latter went for $650,000.

“I’m not a good chess player, but I’m fascinated by how there are aspects of novel writing that resemble chess.”

Earnings on that scale have helped Styron buy the time to craft his novels painstakingly. If his work harks back to the nineteenth century, so do his work habits. He does not use a typewriter, let alone a word processor, but composes all his drafts in longhand. A night owl, he said his mind is too “fogged, obscure, plugged up with cotton” to work in the mornings. He starts writing late in the afternoon and continues through to about 8:00 in the evening, when he stops for dinner.

He revises as he goes along, trying to sense what he calls “the emotional and intellectual rightness of a passage and its connection with what’s to come.

“It’s like a chess game in a curious way,” he said. “I’m not a good chess player, but I’m fascinated by how there are aspects of novel writing that resemble chess: you are anticipating a multiplicity of choices, you’re heading in a certain direction, so you want to make sure that your moves at this point will be symmetrical, so that when you get to point B, everything fits together harmoniously. But sometimes it doesn’t work out.”

The weeks and even months he spends planning and plotting his moves, writing and rewriting, would do justice to a Flaubert. After he had finished the first part of Nat Turner, he had no idea where to proceed next and set the manuscript aside for three months.

“I was in despair,” he said. “And I can’t remember the moment, but there was a moment when it came to me like the famous Westinghouse light bulb. ‘Boing!’ I said, ‘Part two has to be roughly the same length as the first part, and I’ll start doing his childhood.’ It was a matter of discovering the inner architecture.”

Architecture was a word Styron frequently used when describing his efforts to structure a book. Although that implies a certain rigidity, a kind of blueprinting, he is often surprised by the turns his characters take when they come to life, turns that upset his careful plans. One of these surprises—which he called “part of the misery and the fun of writing”—occurred after he’d finished about one hundred pages of Sophie’s Choice. He had composed a monologue in which Sophie portrays her father as a wonderful man who protected the Jews in Nazi-occupied Poland.

“I actually believed that when I got to that point,” Styron said. Then Sophie, as if she had a will of her own, suddenly changed and forced him to rethink the rest of the novel.

“I said to myself, this little numero Sophie is lying about her father. She’s lying her teeth out … in fact, everything that she’s going to tell Stingo … is subject to massive doubt, massive reinterpretation, and the more she goes along, the more she’ll tell a lot of stuff that is plausible but mixed in with the implausible, chief among which was this lie about her father.”

Such unexpected twists drew out the writing of Sophie’s Choice to four years—rather brief by Styron’s standards. Nevertheless, he can see no other way of creating art but to slowly, carefully, put a book together “brick by brick.

“You could bring a hired goon in here and threaten me with a gun, and if I was in one of those situations where I didn’t know the outcome, I’d have to say, ‘Shoot me.’ I am solaced by the belief that if my work has any quality at all, it has this quality because of its long germination time. Had I written with a compulsion to get the books out, they would not be very good.”

“Anna Karenina is one of those characters who are larger than life. That book will live as long as people are able to read because no one wants to consign her to oblivion.”

A preeminent writer of traditional novels, Styron is also an ardent champion of that mode of fiction, which he defends against attacks made on it by the postmodernists. His quarrel with them, he said, was that their obsession with language and technique virtually eliminates story and character, the heart and soul of literature. They also make the “absurd” claim that an avant-garde style of writing is the only valid one, the only measure of excellence.

“My point is that the postmodern argument lacks totally in merit because it’s arrogantly proprietary,” he said. “Why shouldn’t experimental writing be read, discussed, and enjoyed, just as other writing is read, too? Why should one exclude the other?”

Though he admires some contemporary writers (Raymond Carver, Barry Hannah, John Barth, and Donald Barthelme), he finds the work of most writers identified as postmodern to be as full of linguistic tricks as it is empty of memorable characters.

In imaginative writing, Styron said, “language, character, and narrative are interconnected in an almost inseparable way. The three a trinity.” Great literature, great in the sense that it endures, is the art of creating “characters whom people do not want to consign to oblivion.

“I mean an Anna Karenina. Anna Karenina is one of those characters who are larger than life. That book will live as long as people are able to read because no one wants to consign her to oblivion.”

In Styron’s opinion, the lack of such characters in postmodern fiction, and its general aridness, can be laid at the doorsteps of the universities, which have fastened a “stranglehold” on literature.

“I’m speaking especially about academic critics, who are deadeners of art, full of sterile ideas, cliquish.” Their theorizing, he went on, “gives rise to very hermetically sealed writing … works that don’t seek large themes and end up crystallized in little magazines read by twelve readers.

“I think it’s proper for a writer to want to have as large an audience as possible. But that audience is often much larger than the academics consider decent and, therefore, any writer who has written so much as a single best seller is considered suspect. Let’s throw it into the faces of the academics. Practically every person I consider a major writer of my era has been a best seller: Saul Bellow, Norman Mailer, John Updike, John Cheever, Bernard Malamud, Philip Roth.”

That is true of Styron’s era, but, I pointed out, it did not appear to be true of mine. With one exception (John Irving), I could not think of a single serious artist among my contemporaries, those belonging to what might be called the Vietnam or post-Vietnam generation, who had achieved the literary stature and commercial success of a Styron, a James Jones, a Mailer, a Bellow, or a Roth. What, in Styron’s opinion, accounted for this? The decline of readership and literacy in general wrought by television, films, and rock music? Ever-shortening attention spans on the part of the reading public? What?

His immediate response was to take the long view: the audience for serious literature has always been rather small, an elite. True enough, but that answer begged the question. Why was this elite larger for the writers of his generation than mine? After pondering for a few moments, Styron suggested that the fault possibly lies not in the audience, but in the writers, whose alienated attitudes may be cutting them off from a wider readership. He blamed the Vietnam War, which, he said, “created more cynicism than any single event in American history.

“I mean that, and I say cynicism in the classical sense of an utter contempt for even the pretense of values. Why, then, should not the fiction that has accompanied our history during and after the Vietnam War be—well, have a ‘fuck it’ attitude?”

The war and the social upheavals that have occurred in America over the past fifteen to twenty years, Styron continued, have created a “fragmentation of vision” that has, in turn, changed the “tonality of prose fiction.

“It’s vastly different from the era that preceded it. I think I’m saying that Lie Down in Darkness, if attempted again, could not be written … after the Vietnam War; the loathsomeness of what happened there, to me, trivialized such a thing as a girl’s suicide. A girl who’s had a rather rough time, a domestic father-and-mother problem, a lover problem, it’s not a very big deal…. The shift in the tonality, the music, of literary expression is largely due to the war in Vietnam.”

It was the last day of my visit, and Styron was giving me a tour of the barn that he had converted into a writing studio where he could escape the noise and distractions of his four children, three daughters and a son. (Now that they are grown and living out of the house, he does most of his work at the bar in his living room or at his waterfront retreat in Martha’s Vineyard.) The studio was dim, with a vaulted ceiling and a loft where Styron’s old writing desk stood near a window. Over the bathroom hung a quote from a letter Flaubert had written to his mistress: “Be regular and ordinary in your life, like a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your work.”

Styron has followed that advice. His life has been remarkably stable when compared with those of the wild men of American literature, with their shattered marriages, unsettled wanderings, drug habits, and outrageous antics. Styron has been married to Rose, whom he met in Rome, since 1953, has lived in the same house for twenty-nine years, and has remained with the same publisher, Random House, throughout his career.

Not all of his life has been middle-class respectability, however. He possesses what he termed a “modified instability.” While showing me his studio, he suggested that he had “raised some hell” in his day.

“This, “ he said, sweeping his arm over the room, “was the scene of a great deal of carousing … an incredible amount of skullduggery went on here.”

When asked to amplify on that in a later conversation, Styron was more direct and said that his life was not as serene as it appeared. He said he had a drinking problem and was, with the help of a psychiatrist and a course of tranquilizers, struggling to win the battle of the bottle. His health had suffered, and he was overweight, which, he said, could be “attributed to booze. My body is telling me that it’s time to quit. I’m closing the bar, so to speak.”

A private man when compared to professional celebrities, say, Mailer, he did not wish to pursue the subject any further. Prying into a living writer’s personal life, he said, was “trivial, a degrading pastime that is best left to gossip columnists. What’s important is a writer’s work.”

And how, at sixty, did he assess his work, I asked, mentioning that writer Richard Yates had described him as “probably the finest living novelist we have.”

Styron’s self-appraisal was more modest. “I have created and, I hope, will continue to create a few people whom readers will want to read about after I’m gone,” he said. “I still feel that I have years ahead of me to be able to say more with the same talent that I have been endowed with.”

A few months after he said that, Styron very nearly lost those years, and the talent that had produced Lie Down in Darkness and Sophie’s Choice collapsed to the point that he could not read and comprehend a simple newspaper article, let alone write anything. The disease that struck him used to be called melancholia. Its current name is clinical depression—a cloak of despair that falls over a man or woman and makes every waking moment so painful that the victim loses all desire to live.

I was made aware of his breakdown last fall, when Styron called me at my home in Key West and told me he was suffering from a profound depression, which, he then thought, had been caused by tranquilizers prescribed to ease his withdrawal from alcohol. He was, he’d said, considering committing himself to a psychiatric hospital.

The news shocked me because I had formed an image of him as a contented man—contented, that is, compared to other novelists I knew, including myself. Naively, I had persuaded myself that his stable marriage, affluence, and “literary gentleman” style of life had insulated him from the grave misfortunes that seem to befall most American writers.

I heard nothing from or about him for weeks; then, in the winter, I learned from a New York magazine editor that Styron had been committed to the psychiatric ward of Yale–New Haven Hospital.

There was no other word until this spring, when the same editor telephoned with what might be called the good news and the bad news. Good news first: Styron had been released. The bad news was, he’d been so ravaged by his bout with depression that he had abandoned The Way of the Warrior. Worse, the editor implied, Styron’s career might be at an end. This information was more than distressing; I refused to accept the idea that Styron’s voice could be silenced by anything short of death. I wrote him a letter, a somewhat embarrassing letter, for it was full of tough-guy, gung-ho attempts at reinspiring him, the sort of thing a corner-man might say to an exhausted fighter, but inappropriate when addressed to a sixty-year-old author recovering from a nervous breakdown. The gist of it was that writers sometimes need as much courage as warriors, courage of a different kind. If he was abandoning his book for artistic reasons, that was one thing, I said; but if he was doing so because he no longer felt up to it, he had to force himself to keep going. I then invoked the “never retreat, never surrender” spirit of the Marine Corps. It would not have surprised me if Styron had not bothered to reply to such rah-rah, but I received an encouraging answer in early April.

“Let me say again how grateful I am to you for your letter, “ he wrote. “Corny as it may appear, it seems that only a Marine can be truly aware of another Marine’s suffering; you gave me a nice jolt of good cheer. Thanks from the depths. I’m pleased and proud of your friendship.”

And I was pleased that I had done some good after all. Still more pleasing was the news that he had not given up on The Way of the Warrior.

“It’s not so much abandonment,” he’d said in his letter, “as extreme alteration…. I’ve completely restructured the novel.”

Over the phone, we agreed to discuss the book’s radical transformation when I visited New York later in the month.

Styron maintains a pied-à-terre on the Upper East Side where he stays whenever he’s in New York on business or needs to escape the solitude of country living for the stimulation of Manhattan. We met there in late April. He looked little different from when I’d first seen him, but his appearance had improved somewhat; he’d lost a few pounds and was tanned from a week’s vacation in the Caribbean.

While I sat in a chair, Styron stretched out on the bed and spoke about his breakdown in such a clinically detached tone that he sounded more like a student of mental illness than its victim. Educating himself about his disease helped him to conquer it by dispelling some of its strangeness.

“Mental illness has echoes of unspeakable mysteries even to sophisticated people,’’ he told me.

Nevertheless, his account of what he called his journey to the edge of the abyss was almost supernaturally frightening.

“In clinical depression,” he said, “the psychological element merges into a chemical imbalance. Brain chemistry goes haywire, and when that happens it is catastrophic, an explosion in the mind, like the space shuttle Challenger going off in midair. Stress and anxiety have an effect on your brain’s neurotransmitters, removing from your consciousness any ability to receive impulses of pleasure. A palpable shroud of melancholy descends on you and becomes a pain as severe as a crushed knee. You cannot bear living any longer. The act of daily living, the whole diurnal process, becomes such a struggle you want to get out of it.”

Styron, admitted to the hospital last December 14, altered his ideas about suicide. Before the depression clobbered him, he’d considered the taking of one’s own life a deranged act; afterward, he saw that it could be a rational, calculated decision.

“There was a period in December when, if I had had the ultimate pill, I would have taken it.”

Indeed, Styron made an attempt to obtain the ultimate pill. Shortly after his admission, he telephoned a friend, an ex-convict who himself had suffered from depression while in prison and understood the nature of the disease. Styron asked his friend for “the black pill, “ their code name for a lethal dose of barbiturates.

“He told me he’d bring it if I really had to go out, but he advised me to wait four or five days. I did. Sure enough, I started to come out of it.”

A full two months would pass before Styron came out of it entirely. So severe was his melancholy that when a staff psychiatrist asked him to read the lead paragraph from a New York Post crime story and then tell what it was about, Styron was unable to remember even the gist of the article.

“That’s when I realized how far gone I was. Out of a mere 150 words, I couldn’t recall one. The story could have been about a tennis match for all I knew.”

Convinced he would be hospitalized indefinitely, Styron telephoned Rose and calmly asked her to divorce him, so she would be free to remarry, and to make plans to have him transferred to a state mental hospital to avoid exhausting their $250,000 medical-insurance policy. He revised his will and dashed off what he termed melodramatic notes to fellow writers such as Peter Matthiessen. Tested, examined, and analyzed, pumped full of lithium, sleeping pills, and antidepressants, he experienced “the closest thing to hell” he’d ever known.

Styron’s hospitalization turned into an almost Dantesque inner journey, from darkness into a new and purer light.

“You learn a lot about yourself. You lose your self-esteem. You tell yourself, ‘I’m not worthy to be pulled out of this. Everything I have ever done is a bloated monstrosity of my ego, and I have committed atrocities against my fellow man that are unpardonable.’ You feel guilty for everything you’ve done. Little insults you’ve committed become crimes, and all your achievements, in your own mind, are reduced to a mound of ash.”

Drugs and psychotherapy, in Styron’s opinion, did little to bring him out of such despair. The support of his wife, children, and friends such as Gloria Jones (James Jones’s widow) was of far greater help, he said.

“I don’t know what would have become of me if I hadn’t had people like Rose. I can’t imagine anything more horrible than suffering through depression alone.” Styron grinned. “Gloria was funny. She told me to see an Irish shrink because Jewish or Protestant shrinks would tell me my entire problem was alcohol, but an Irish shrink wouldn’t be so militant about having a beer now and then.”

Mrs. Jones’s tongue-in-cheek comment was not without an element of truth. Styron discovered that excessive drinking had been only one of the root causes of his disease. The others were buried in his family history, in his very genes.

“There is a genetic link,” he said. “Both of my parents were depressives, and people who have lost a parent early in life are more likely to get it. I lost my mother when I was a boy, so I had two strikes against me right there.”

In the cloister of his hospital room, Styron found another source of his breakdown: his new novel. He had been having serious problems with it when he and I had met the year before, he confessed. The book, though he’d been working on it for about two years, hadn’t been going anywhere. Some crucial element was missing, but he could not find what it was. The more frustrated he became, the more stress he felt and the more he drank to relieve the stress; the more he drank, the more depressed he grew; then he drank some more to lift himself out of the depression until, finally, he crash-landed in the hospital.

He was released on February 2. Every dime of his emotional and intellectual reserves spent, he was convinced he could not continue work on The Way of the Warrior and thought his career was finished.

“I told that to Rose, and she said that that was all right, that I’d achieved a lot and that she and my children would love me no matter what I did. She suggested that I retire and just putter around the house.” He gave another wry grin. “That didn’t appeal to me. I could just see signs posted around the lawn and hedges: STYRON—BEGIN PUTTERING HERE.”

He spent the next few weeks attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and wrestling with invisible devils: the lingering effects of his breakdown and the elusive solution to the problem with the new novel. Then, in a story as dramatic as anything he might have written, he found the answer.

“It came to me after an AA meeting. I was talking to a woman whose husband had been a regular officer in Vietnam, and all of a sudden, everything became quite clear. It was as if that woman were giving me a message. A translucent curtain seemed to lift, and I saw, as in a vision, the face of a young man in a wheelchair, with one arm and both his legs gone and a look of absolute rage on his face, and said to myself, ‘My God, I’ve got it!”’

What he “got” was the realization that, in writing about World War II and the Great Depression, he’d been “barking up the wrong tree.” The world war and Vietnam had to be linked if the new book was to have any integrity or power.

“If I tried to write about Vietnam from the inside, it would sound hollow, no matter how well I wrote, because I wasn’t there.”

“Vietnam was a logical offshoot of post–World War II America,” Styron said. “It was inevitable, because our entire national identity was bound up in its relationship to worldwide communism. So, you see, coming out of the hospital caused me to realize what I really wanted to do in this book.”

But that recognition brought new problems and fears. Although Vietnam had receded to the point that Styron could deal with it in the historical context in which he is most comfortable, he knew he could not write about the war directly.

“If I tried to write about Vietnam from the inside, it would sound hollow, no matter how well I wrote, because I wasn’t there. It was a matter of finding the right perspective. I said to myself, I can’t do this. I can’t make the leap, like Stephen Crane.” He was referring to The Red Badge of Courage, the quintessential book about Civil War battles, which was written by a man who had not fought in the conflict.

His difficulty in finding the right angle of approach was analogous to the one he’d encountered while writing Sophie’s Choice. Styron wasn’t at Auschwitz, either. He’d found the solution by deciding to write the story from the viewpoint of a woman outside the camp, Sophie Zawistowska, mistress to the commandant.

In the new version of The Way of the Warrior, Styron solved the point-of-view problem by choosing to treat Vietnam through the relationship between the crippled young veteran and his father, who is an aging version of the Lieutenant Stiles in the original draft of the novel. As wary as ever about talking about a work-in-progress, he declined to go into further detail.

“All I can say is that I have to have a sense of certitude, of rightness and inevitability, before I write something. And I have that now with this book.”

His greatest fear is that he lacks the strength to see the project through. Styron said he has felt a “falling of energy” since his release from the hospital. He estimated that the novel would need at least two to three years’ more work before its completion. His doctors assured him that he has a 95-percent chance of never suffering a recurrence of depression, but there is another adversary confronting him: his age.

“I keep thinking about Hawthorne, dying in his sleep at near sixty. He lost his mind in his last year. He couldn’t even recall the names of his characters. It saddens me, being the same age.”

Styron paused, gazing abstractly out the window toward the street.

“Sixty. Sixty isn’t that old anymore, is it, Phil?… I guess not, but it isn’t a very pleasant number, is it?” Styron asked rhetorically. “Still, I feel a passionate determination to put everything I can into this book. I want it to be the strongest statement I can make about American life. I hope I have the strength for it. You know, readers want to see a writer leap into unknown territory and succeed, but, on the other hand, they don’t want to see him exceed his limits and fail.”

Writer and warrior—each needs his own special brand of courage to face his own special brand of enemy. For an author of Styron’s stature, the main enemy is often himself. He needs a unique courage to confront and overcome this inner adversary and can succeed only by venturing into the unknown and out of the safe limits imposed by his fears of failure. I resisted giving Styron another Marine Corps–style pep talk, but I suddenly recalled the motto of my old regiment, the Third Marines: Fortes fortuna adjuvat—Fortune favors the bold.

[Photo Credit: William Waterway via Wikimedia Commons]