In the Great Depression 1930s, I lived across the street from South Field, which was a breeding ground for Lou Gehrig’s home runs at Columbia University. In those days, many of the youngsters in the neighborhood collected autographs of ballplayers, some famous and some not so famous. Most of us did it for memory and not for money. We hunted ballpark entrances and hotel lobbies, where we could take our pads and scrapbooks to catch players in town to play New York’s Yankees and Giants, and the Brooklyn Dodgers. Only day games were played at the time, so many players got up early and spent pregame hours sitting and schmoozing in the lobby, and maybe doing crossword puzzles.

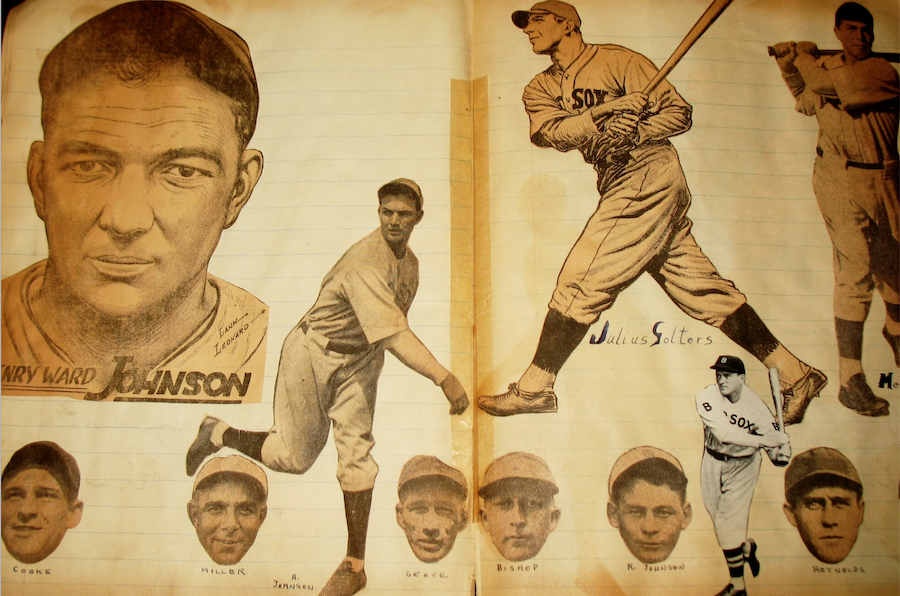

The most remarkable aspect of my autograph pursuit was that most of my pals and I were able to identify these players. Without television, and relying mainly on news photographs, mostly from The Sporting News, we knew immediately who Heinie Manush was or Smead Jolley or Tommy Thevenow. We knew this was Charlie Gehringer and that was Ed Brandt. I was much better at recognizing players than at doing my math homework.

Recently, as I looked over my 75-year-old scrapbook, its yellowed, crumbling pages fatigued by time passing, I realized that my collection revealed a singular cultural footnote: it seemed that most of the players, regardless of status in the game, signed with their nicknames, not their given names. One notable exception was Paul Dean. He refused to sign as Daffy, even though his celebrated brother, Jay Dean, scrawled Dizzy next to his photograph.

There seemed to be an amusing story with almost every signature that I obtained.

When I encountered the ageless Cornelius McGillicuddy (a k a Connie Mack) one day in a hotel lobby off 71st Street, he showed some irritation with me.

“Young man,” Mack, the manager of the Philadelphia Athletics, said in a soft voice, “do you realize that you have interrupted me while I was in conversation?”

I was almost reduced to tears by his reproach. Mack, perhaps sensing I was upset, signed his name for me, anyway. But I had learned a lesson for a lifetime: never interrupt someone when he is talking, especially if it is Mr. Mack.

Every so often, there was an unanticipated contretemps. In another hotel lobby some weeks later, I asked Robert Moses Grove for his autograph. Then pitching for the Red Sox, Lefty Grove was one of the game’s incomparable southpaw pitchers — the Sandy Koufax of his time. He also possessed a volcanic temper.

At the moment I approached him, Grove was decked out in an egg-white Panama suit. Thrusting my autograph book into Grove’s hand, I turned to a page devoted to pictures of him. I asked politely if he would sign for me as I handed him my pen. He took the pen and signed Lefty Grove.

But as he returned the pen and book to me, he gazed down at his pants. A rivulet of dark, blue ink had dribbled down from his fly to his right knee.

Ashen-faced, Grove grabbed me, not so gently, by the back of the neck. In my panic, I thought he was about to fling me across the lobby at 100 miles per hour, a smidgen faster than his fearsome fastball. Instead, thank heaven, he thought better of it.

“I don’t ever want to see you again!” Grove said with a growl.

I made certain he never did.

If I had to pick the true highlight of my autograph-hunting days, it had to be the brief encounter with Honus Wagner, probably the greatest shortstop in baseball history. At the time, he was a popular coach with the Pittsburgh Pirates, after playing 17 years as their shortstop.

When I walked over to him, he appeared to be sleeping or just dozing off in the hotel lobby. Smiling, he wrote his name, J. Honus Wagner, on the bottom of a tiny photograph of his craggy face. I still recall his big ears and exceedingly large nose. I suspected he might have had a mouth full of false teeth. He thanked me for asking him to sign.