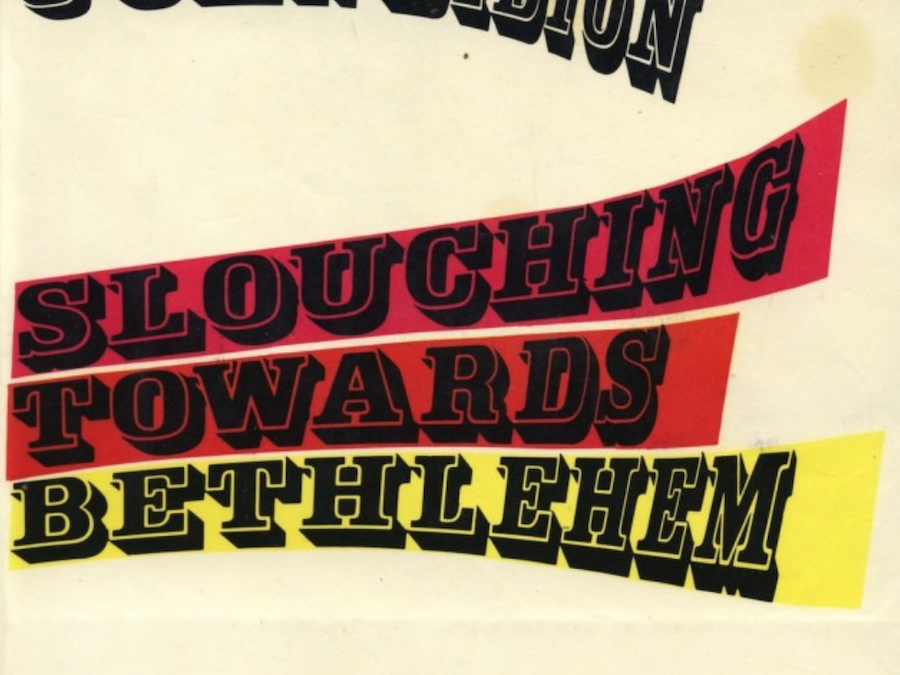

Both as a novelist (Run River, 1963) and as a reporter and essayist, Joan Didion is one of the least celebrated and most talented writers of my own generation (“Silent,” B.A.’s circa mid-1950’s). Her first collection of nonfiction writing, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, brings together some of the finest magazine pieces published by anyone in this country in recent years. Now that Truman Capote has pronounced that such work may achieve the nature of “art,” perhaps it is possible for this collection to be recognized as it should be, not as a better or worse example of what some people call “mere journalism,” but as a rich display of some of the best prose written today in this country.

Though not as difficult to interpret as Susan Sontag, or as smoothly digestible as Theodore White (the “President-Making” one), Miss Didion surely deserves a wide audience among those readers who may still be turned on by such qualities as grace, sophistication, nuance, irony and, as Miss Didion observed in another context, “what used to be called character.”

The author writes about the contemporary world—quite often the Western United States where she grew up and where she has returned after the writer’s almost obligatory boot-camp training in New York City—and though her own personality does not self-indulgently intrude itself on her subjects, it informs and illuminates them.

The reader comes to admire what can only be called the character of the observer at work looking in as well as out, noting, for instance, in a piece about a young California Maoist that is a classic portrayal of a certain kind of political zealot of either left or right:

“As it happens I am comfortable…with those who live outside rather than in, those in whole the sense of dread is so acute that they turn to extreme and doomed commitments. I know something about dread myself, and appreciate the elaborate systems with which some people manage to fill the void, appreciate all the opiates of the people, whether they are accessible as alcohol and heroin and promiscuity or as hard to come by as faith in God or history.”

In her portraits of people, Miss Didion is not out to expose but to understand, and she shows us actors and millionaires, doomed bridges and naive acid-tripper, left-win ideologues and snobs of the Hawaiian aristocracy in a way that makes them neither villainous nor glamorous, but alive and botched and often mournfully beautiful in the midst of their lives’ debris. Her portrayals remind me most of the line of a great poem of Robert Frost that says, speaking of us all, “weep for what little things could make them glad.”

Miss Didion is the only writer I know who has captured something of the real mystique and essence of Joan Baez, a frank but elusive subject whom more than one reporter has muffed in the most hopeless manner. (I know, I am one of them.) The fragile innocence as well as the pathos of the students at Miss Baez’s Workshop for Non-Violence are caught in Miss Didion’s description of one of their sessions breaking up as the sky turns dark in the late afternoon, and how they are all “reluctant about gathering up their books and magazines and records, about finding their car keys and ending the day, and by the time they are ready to leave Joan Baez is eating potato salad with her fingers from a bowl in the refrigerator, and everyone stays to share it, just a little while longer where it is warm.”

The title piece is about Haight-Ashbury, and conveys the complexity and the “atomization” of the hippie scene not as the latest fashionable fad, but as a serious advanced stage of a society in which things are truly “falling apart” as in Yeats’s poem. Compare this piece with Time magazine’s hapless cover story on the hippies last year, and you see why “group journalism” is usually inferior to a single, talented writer using the “method” explained by Miss Didion: “When I sent to San Francisco in that cold late spring of 1967 I did not even know what I wanted to find out, and so I just stayed around a while, and made a few friends.”

This is how the best things are always done—a fact they won’t believe when you try to explain it at a writer’s conference. (They think you’re keeping a secret about how it’s really done.)

“Goodbye to All That,” an essay on the author’s years in New York, does for my generation’s love-hate affair with that capital what Fitzgerald’s essay “My Lost City” did for the generation of the twenties. Speaking go her arrival in Manhattan fresh out of college, Miss Didion explains that during the first few days the only thing she did was “talk long distance to the boy I already knew I would never marry in the spring. I would stay in New York. I told him, just six months, and I could see the Brooklyn Bridge from my window. As it turned out the bridge was the Triborough and I stayed for eight years.”

If there are any readers who do not appreciate that last sentence, this reviewer is powerless to save them.