Forgive me, but I prefer to remember the old Harry.

The St. Louis Harry. The Harry who was heard but rarely seen. The Hall of Fame Harry who described baseball as sharply and dominantly as Bob Gibson pitched. The Harry Caray who made summers so magical and memorable for so many millions in so many Middle American states.

The old Harry was the best baseball broadcaster I ever heard, and that includes Vin Scully and Mel Allen. If you never heard that Harry, I feel for you. I enjoyed the Chicago Harry too, but he had spoiled me too much to embrace him the way Cubs fans did.

To me and many of my boyhood friends, the Cubs Harry turned himself into a lovably goofy sideshow for a franchise that had little else to offer its faithful. Harry Caricature, we called him.

The one thing he couldn’t do with his voice was sing. Yet Cubs fans stayed until the seventh inning just to watch him lean out of the press box and lead them through “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.”

The St. Louis Harry took me out to the ballgame via radio, and I never wanted to miss the eighth and ninth. That Harry was so good he ruined the first big-league game I saw in St. Louis. It didn’t quite measure up to the ones Harry had brought to Technicolor life for me as I lay in bed with the lights out.

As the home opener approaches, allow me to pay my last respects to that Harry, who died less than two months ago. Holy cow, was he talented.

During our teenage years, Harry was to my buddies and me what Wolfman Jack was to American Graffiti.

That Harry was known and cherished by millions from North Dakota to south Texas. That Harry did games for 50,000-watt KMOX out of St. Louis, along with affiliate stations from here to Petticoat Junction. For all I know, Harry willed his voice into homes and cars from the halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli.

I’ve heard from people who had Twilight Zone–like Harry experiences while driving alone on a late summer night down some lonesome road in, say, Georgia or New Mexico. One minute, they were listening to Mel Tillis on KCOW; the next, Harry was saying, “Two-two to Cepeda. McCarver would be next.”

Some nights, Harry so electrified games that he probably interrupted signals up and down the dial. Oh, did I love hearing him say something as trivial as “two-two.” Harry hit the “ts” so hard that he made “two-two” sound more dramatic than “Four score and seven years ago…”

Harry didn’t just say words; he fired them at you like rising fastballs, emphasizing odd and unpredictable syllables. “Ho-LEE cow!” he might say.

During our teenage years, Harry was to my buddies and me what Wolfman Jack was to American Graffiti. Harry’s voice was omnipresent on hot nights in Oklahoma City. You ate dinner and did your homework to Harry. You cruised for “chicks” with Harry on the radio of your ‘65 Mustang or ‘67 Camaro. Girls wouldn’t go out with you a second time because you wouldn’t let them change the station. Who needed the Beatles or Stones when you could listen to Harry rock and fire?

We considered him a higher authority. Harry knew the game and he wasn’t afraid to constructively criticize those who played it.

The St. Louis Harry did not mispronounce names. A stroke hadn’t yet robbed him of his diction. He was not yet Everyfan, broadcasting from the bleachers, drinking beer and getting a little crazy with the Toms, Dicks and Harrys. We didn’t want the St. Louis Harry to be one of us.

We considered him a higher authority. Harry knew the game and he wasn’t afraid to constructively criticize those who played it. It was almost as if you were listening to the Cardinals manager, supplying you with his clever, unedited insight.

Harry was not as eloquent as Scully or as folksy as Allen, but he could tell stories as effectively as either. For my money, he was more consistently entertaining than Scully or Allen because he was more passionate. Harry’s voice conveyed drama the way wire does current. Harry could jolt you out of a backseat kiss.

Of course, through the ‘60s, Harry was fortunate enough to describe many classic moments. If the Cardinals hadn’t played in three World Series, maybe Harry wouldn’t have sounded quite so great. But I believe I would have listened to the ‘60s Harry if he had been doing the Toledo Mud Hens.

I sometimes wondered if Harry, in effect, died for the Cubs cause—if he sacrificed some of his credibility for the good of so many bad teams.

That Harry didn’t yet wear cartoon-size glasses. That Harry wasn’t yet a “Cub fan and a Bud man” or the Mayor of Rush Street. That Harry didn’t yet cultivate the image of the broadcaster who could outdrink anyone in the sports bar. For me, watching the Cubs Harry was sometimes like watching Olivier do vaudeville.

I sometimes wondered if Harry, in effect, died for the Cubs cause—if he sacrificed some of his credibility for the good of so many bad teams. If possible, Harry became a bigger attraction than Wrigley Field itself—bigger than the ivy. He once said that a full house would show up just to sing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” with him. That was sadly true.

But not nearly as sad as this: Saturday Night Live began doing skits of Harry as a babbling, mush-mouthed talk-show host. To me, this was appalling. This was supposed to be my Harry, the greatest ever. Oh, take me back to the ballgame, Harry.

I loved him as much as Cubs fans did, but I prefer to hold on to earlier memories. Summer hasn’t been quite the same without him. On clear nights, maybe, you can still hear him on some lonesome two-lane: “Two-two to Cepeda…”

Excerpted from From Black Sox to Three-Peats: A Century of Chicago’s Best Sports Writing (University of Chicago Press), edited by Ron Rapoport and featuring stories from the Chicago Tribune, the Chicago Sun-Times, the Chicago Daily News, and the Chicago Defender, among other papers.

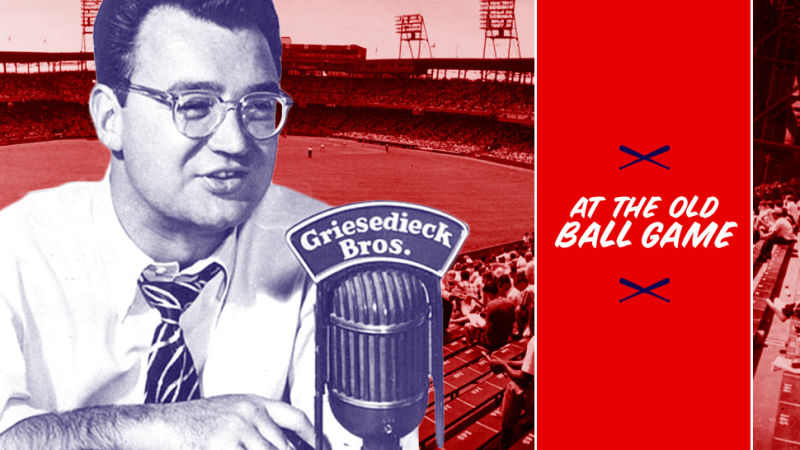

[Featured Image: Jim Cooke]