The scene: an informal dinner party on the rooftop of a brownstone in the East Seventies. The people (with one exception): congenial, civilized, charming. The conversation: charming, civilized, congenial.

Until … until someone makes the mistake of asking me what contemporary writers I like. This is a mistake other people at other parties have lived to regret. Because I can be, well, a little fanatical on the subject.

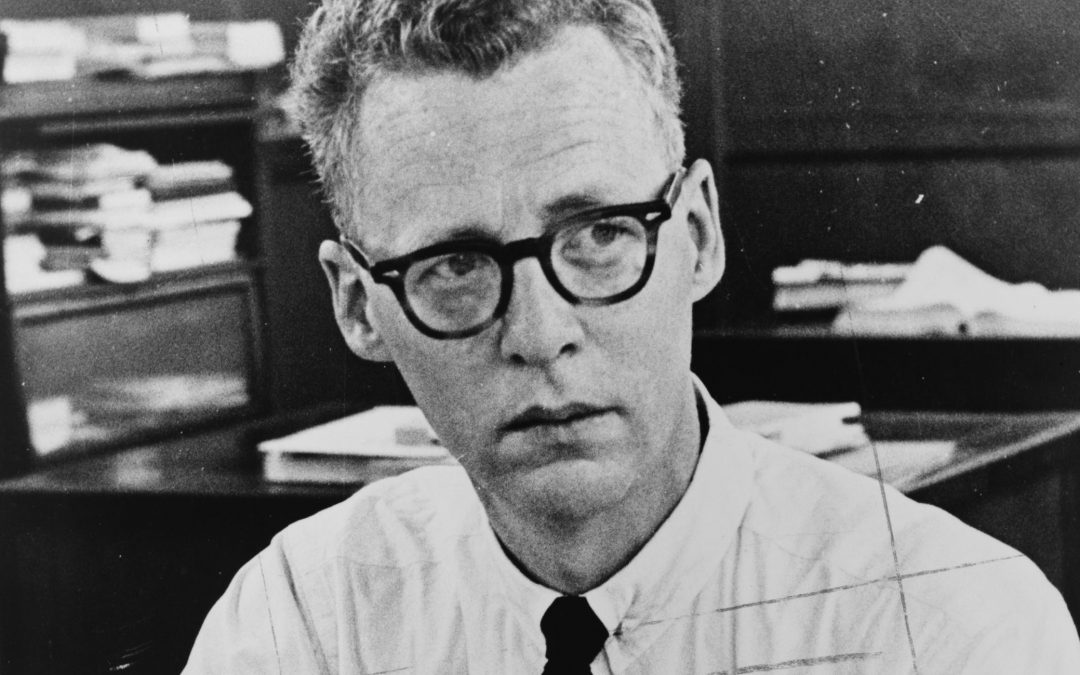

Particularly (as was the case that evening) when I try to explain to people that Murray Kempton is the best writer of prose in America, and I get blank stares from half the group and someone from the other half says something like “Murray Kempton? You mean the newspaper columnist?” with a maddening mixture of incomprehension and disdain. To me it’s akin to some late-Sixteenth-century twit saying, “Thou meanst William Shakespeare, the theater person?”

At that point, with the evening irretrievably ruined for me, I proceed to ruin it for everyone else by launching into a long feverish disquisition on the indispensability of reading Kempton; on the indispensability of reading Kempton to any literate human who cares about the pleasures and possibilities of the English language; on the indispensability of reading Kempton to any student of human nature who seeks to understand the way the passions of the human heart shape and subvert the pageant of public events.

In fact, I conclude, you can’t pretend to understand life in New York City, indeed the whole drama of American civilization, without Kempton’s vision and insight: He’s nothing less than our Gibbon.

For a moment after I conclude with this ringing declaration, there is silence on the rooftop, nothing but the faint rumbling of air-conditioning exhausts on the windows of the adjacent building. I begin to feel I’ve succeeded in sweeping away all possible objections with this final hammer blow, that my oratory has shamed the assembled company into silent contemplation of the insufficiencies of their lives. I am particularly pleased with myself for the finale, the “our Gibbon” line.

And then a voice pipes up, breaking the silence: “Uh, Art Gibbon—isn’t he that sportswriter?”

Oh, well. I guess I deserved that. But Kempton doesn’t. He deserves better of us. Yes, he got a long-overdue Pulitzer Prize a couple of years ago; but here he is, appearing four times a week on almost every newsstand in New York now (in New York Newsday), and yet the recognition and appreciation he gets is so incommensurate with what his astonishing achievements deserve that it constitutes a major injustice, a disgraceful city scandal.

That night, the night of the Art Gibbon debacle, I vowed I was going to do something to correct this injustice. First thing the next morning I would gather up all the scattered Murray Kempton columns I’d been tearing out and stashing all over my apartment; I’d call up Kempton and arrange an interview; and I’d whip out a story that would prove to the doubters, to the Art Gibbon types, to the pseudosophisticates who look down their noses at “newspaper columnists,” just how essential regular reading of Kempton is to anyone who pretends to be civilized.

I thought it would take me a couple of weeks. In fact, it’s taken me more than a year since the Art Gibbon incident.

I have some excuses. I know you don’t want to hear them, but I don’t care, they’re important. First of all I decided that, in order to do justice to Kempton, in order to support the grand Gibbonian claim I was making on his behalf, I needed to reread Gibbon’s History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire in its entirety. Believe me, that ate up a lot of time, even skimming, as I’ll admit I did, some of Gibbon’s extended accounts of the succession of the late emperors of the East, whose interminable intrigues were profoundly—and literally—Byzantine.

“My family was very Confederate,” he says. “And I always had a kind of Confederate view of everything. Losing-side consciousness is very important.”

But in the course of rereading The Decline and Fall for the first time since college, I made two surprising discoveries. Gibbon is much better than I remembered. And in some respects Kempton is better than Gibbon.

The thing I never realized about Gibbon in the miserable circumstances of my sophomore year was what a terrific—and wicked—sense of humor the guy has. For sheer black humor nothing beats his ostensibly polite efforts to explain the “reasoning” behind the early church councils’ distinction between orthodoxy and heresy. His account of the persecution of the heretics is amused and detached on the surface, but beneath the elaborately counterpoised antitheses of his prose there is a stirringly passionate disgust. Kempton has that quality too. The baroque civilities of his notoriously knotted sentence structure are capable of concealing and revealing passionate responses to events.

What makes Kempton’s achievement so remarkable is that Gibbon was writing with, for the most part, ten centuries of hindsight. Kempton somehow manages, four times a week, on deadline, to give events just a few hours old a focus that seems to reflect a thousand years of accumulated wisdom and perspective. He is this city’s single most underappreciated asset.

This has been a particularly good year for reading Kempton because if he can be said to have a specialty, it is as a connoisseur of scoundrels. And this past year—which began with Donald Manes and the city corruption scandals, which featured four simultaneous major Mafia trials, which yielded up Dennis Levine [the first major insider trader of the ’80s to be caught], who yielded up Ivan Boesky, and which followed that up with Iran-contra—has given Kempton a joyful surplus of rogues to write about.

What he’s always done best is make distinctions between degrees of scoundrelhood. Consider, for instance, his take on the investment banking scandals. Rather than merely rail against corruption and immorality in the abstract, he distinguishes between the social productivity of the robber barons of a century ago and the comparative sterility of contemporary corruption.

Of Dennis Levine, Kempton writes:

Everything in Levine’s history would seem to illustrate the splendid freedom from conscience that made giants of the robber barons but in his case most painfully illustrates the social decline that becomes irreversible when commercial immorality abandoned all productive functions.

A hundred years ago Levine … would have gone to engineering school and emerged to flog Chinese laborers at the rail spike, bake Slovaks at the blast furnace … hang Molly Maguires or shoot Wobblies at the pit face.

Deeds of this description have the inescapable odor of the foul, but when they were done we had the Union Pacific, Pittsburgh, and Detroit to show for it.

And here’s Kempton on another unappetizing scoundrel, bagman-turned-state’s witness, Geoffrey Lindenauer. He quotes a bribe-trial witness’s description of Lindenauer oozing around to put the touch on him. Kempton then asks “Breathes there a man with a soul so dead that his dignity would not revolt when the likes of Lindenauer call out, ‘Hi, partner’?”

On the exposure of Roy Cohn’s affectional preference: “Roy went astray in no end of ways, but I had always thought of him as the last of ambulant creatures to be misled by moonlight and the rose.”

Again on the declining productivity of contemporary corruption: “The difference between then and now is in the erosion of greed’s social utility, dreadful as it inarguably was … the robber barons sacked the earth and flayed the toiler, but they left mines and mills and railroads behind them. Their greed was the terrible engine of progress. Ours is only the bedizened fellow traveler of decay.”

And striking a Gibbonian note on observing the prison-thin figure of Mafia don Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno: “He has come to look like some bust in the old Roman style, toppled over somewhere in the decline and then salvaged from the ruins of the empire.”

But as I was reading over a year’s worth of Kempton columns in preparing for my conversations with him, I noticed another theme emerging with unexpected frequency: passionate, almost chivalric, defense of women in trouble. Some of his finest columns have been about women—from his defense of murdered teenager Jennifer Levin against the insinuations of her murderer, Robert Chambers, to appreciations of political women from Bella Abzug to Nancy Reagan. He can go from commiserating with Geraldine Ferraro (“the troubles of Geraldine Ferraro commence to break the heart … and yet [she displays] an inflexible gallantry”) to a sympathetic account of Joey Heatherton’s legal troubles over the passport-clerk-head-whipping incident. Joey, he tells us with great delicacy, is “a young woman who has not been too well used by life and, it must be conceded, has not always used life impeccably in return.”

The latter is a perfect example of Kemptonian observation: Utterly aware of the flaws in the fallen nature of his subject and yet good-naturedly tolerant of them, he passes a sentence that combines both judgment and absolution as, I suppose, the best of the bishops from whom he’s descended would.

His affectionate reverence for women can be seen in his sly tribute to the powers of Victoria Gotti, the reputed Godfather’s formidable wife. Kempton attends the jury-selection phase of the Gotti trial and notes that while most of the prospective male jurors have been giving fearful excuses for not sitting in judgment on Gotti, the prospective women jurors have not.

Probing this mystery, Kempton notes various publicly reported instances of Victoria Gotti’s wrathful temperament: “Gotti may or may not have been too loose in his trifling with law and order, but he has to know better than to trifle with her.” The women jurors haven’t missed this aspect of the alleged Godfather’s marriage, Kempton suspects: “There are particular things that only women know, and we can with reason surmise that they have noted on John Gotti’s countenance the marks of the henpecked husband invisible to his fellow man. No wife can fear even the most dangerous of men once she suspects he fears his own wife.”

Kempton’s even able to summon up sympathy for Lillian Goldman, the aggrieved wife of Sol Goldman, who is “almost the grandest, if not quite the gamiest, of our realtors,” as Kempton delicately puts it. Kempton’s column about their complicated separation and reconciliation litigation is a classic for the hilarity he evokes with his bone-dry deadpan account of this domestic comedy. It seems that under their separation agreement, husband Sol provided an apartment in the Hotel Carlyle for wife Lillian. When he sought a reconciliation (the motive for which, Kempton suggests, may have been less romantic longing than concern about the loss of half his billion-dollar empire, which a divorce would entail), Sol encouraged Lillian to move back in with him by threatening to cease paying her rent at the Carlyle.

“This may of course have been the only way a landlord knew for saying how much he wanted a lost one to return to his bosom,” Kempton observes dryly. “But, if that were the case, Lillian Goldman remembers no other sentimental touch except the moment when he held up their joint tax return for 1985 and said, ‘See, you’re still my wife.’ ”

Kempton’s chivalric exertions have been most passionate in the columns he’s devoted to the Jennifer Levin case. He’s bitterly outraged by the way her accused murderer Robert Chambers has attempted to save his skin by blighting Levin’s reputation. And, again, in the most dry and deadpan way, he introduces a facet of the case that could have a devastating impact on Chambers’s fate: “There is, to be sure, gossip, however unsubstantiated, that Chambers took Jennifer Levin’s earrings with him before departing, which were it true, might hint faintly at susceptibility to tokens of sentiment, but there is otherwise no expression of Chambers’s that does not smoke the fuels of hatred.”

It’s probably safe to say that Kempton is being wickedly ironic when he suggests Chambers took Levin’s earrings as “tokens of sentiment. In fact, he seems to be suggesting Chambers stole them off her dead body, a suggestion that, if true, might tend to undercut Chambers’s assertion he was an innocent victim of Levin’s “rough sex” ardor.

Kempton closes this column with a melancholy peroration on the decline of chivalry: “Men and, to a lesser degree, women have always had too much trouble keeping their tempers in each other’s company; but before chivalry passed into the grave there was some respect for duty to the fiction that they cared about the weak and vulnerable. But now all men are free, which means any number of them are lost.”

I ask Kempton if he considers himself a romantic.

“I hope I consider myself a gentleman,” he amends. “Women don’t have to have chivalry …. Chivalry’s a male virtue. I think there’s an awful lot of misogyny loose,… so someone’s got to stand up for them.”

Kempton is descended on his mother’s side from one of the most illustrious of the First Families of Virginia (the Masons—several men on his father’s side were Episcopal bishops of Virginia).

Does your concern for chivalry stem from your descent from Southern aristocracy? I ask him.

“My family was very Confederate,” he says. “And I always had a kind of Confederate view of everything. Losing-side consciousness is very important. For instance, it explains the Miranda decision.”

How so?

“Hugo Black came from the only county in Alabama that stood by the Union. Earl Warren’s father was a railroad striker in the Debs strike. He was blacklisted and he spent two years in—”

Really?

“It’s fascinating. The losing side—if you don’t get too excited about the possibilities of ever being the winner it’s a very good way to grow up. I’d recommend it. I sort of grew up on the losing side. It didn’t do too much for my character, but there are people whose character it’s improved.”

And yet, despite his Confederate background, Kempton was doing dangerous civil-rights work in the rural South in the ’30s. After we ordered dinner (we met in an Italian place called Poletti’s near Kempton’s West End Avenue apartment), I mentioned to Kempton I’d just come across a reference to him in a fascinating book (Song in a Weary Theme by Pauli Murray, a black woman who was an early civil-rights activist). She describes traveling through the mean backwoods of rural Virginia in the late thirties and working with “a freelance journalist named Murray Kempton” on a pamphlet in defense of a black sharecropper condemned to die because he allegedly shot his landlord. How did a scion of Confederacy end up doing that? I asked Kempton.

“People ought to remember people who rode wild horses.”

He says his involvement in radical politics grew out of a quixotic impulse to go to sea because his cloistered college life at Johns Hopkins didn’t seem “real” enough to him at the time. “When I was in college I went to sea, which is about 1936, but while at sea I joined the Communist party. I didn’t join it with anything of idealism, as I remember it. The thing was … I needed a job and the so-called rank and file of the [Seafarers International Union] went on strike, and I was doing publicity, and—” he adds with typical self-deprecating irony—“it’s important to remember, there was a time in the United States when you joined the Communist party to advance your career. No, it wasn’t much of a career, but the entire membership of the Port of Baltimore was the Communist union. [There was] a thing called the Travelers’ Club, which was very important in the movement.”

The Travelers’ Club?

“The Travelers’ Club. Everybody went around saying—about as authentically as Lillian Hellman saying she was able to carry underground messages to the German Resistance—they were ‘traveling’ which I never did …. Very romantic organization.” He quit the party after about a year.

“I was sort of unhappy about the Moscow trials. I was unhappy with their position on the war, of course. So I quit. Then I joined the Socialist party, that is, the Norman Thomas Socialist party, and then I resigned and I worked for an organization called the Workers’ Defense League and got involved in the Waller case, the sharecropper who shot his landlord.”

Kempton wrote a book about that era, about contemporaries both famous and obscure who had joined the party and left, and the varying paths their lives had taken in the disillusioned aftermath. The book is called Part of Our Time and it’s probably the only piece of twentieth-century American political writing on that subject that can stand unashamed next to Orwell. I know it changed my life. The summer of my junior year of high school I was taking remedial driver’s ed, and in the course of haunting an empty school library, I came across Part of Our Time; it was a sudden revelation that writing about “current events” didn’t have to partake of the terminal boredom of civics classes, that at its best, political writing can partake of the drama, the passion—and the methods—of great novels. It also was an introduction to irony, paradox, and a tragic, loser’s-side sense of history, to a sense of the Kemptonian complexity of life.

Kempton now looks back with a mixture of affection and sadness for the people who shared the excitement of that era.

“I used to know a guy named Paul Hall [head of the Seafarers International Union, whose progress from radicalism to respectability Kempton chronicled]. And Paul used to have the most wonderful expressions, and he’d always say of somebody, ‘You know I always got along with him—I rode a lot of wild horses with him.’ ”

He speaks a bit sadly of the people he rode wild horses with in the 1930s, People whose tragedy it is “to have your history remembered only by the likes of me, who, if you committed a bank robbery, would probably be more admiring and appreciative. But people ought to remember people who rode wild horses.”

Speaking of bank robbers, another recurrent—and controversial—theme of Kempton’s journalism has been his ability to find a kind word to say for the Mafia dons and organized criminals he’s come to know in the course of covering their courtroom travails.

I ask him about that and he tells me he has no special reverence for them.

“People are very romantic about these guys, but the only thing I ever learned is that if you talk to gangsters long enough, you’ll find out they’re just as bad as respectable people. [Is that brilliant time-delay irony or what? Still perhaps my favorite Kempton line.]

Still, the theme of much of his coverage of the “Commission” trial—of the CEOs of the five big Mafia-family corporations—has been the decline in standards in the boardrooms of organized crime.

He compares the elders of the Cosa Nostra with their uncivilized successors.

“Gotti does not measure up, for my taste …. He’s not open to the maturing experiences that bring a gangster to the proper sense of his dignity. Gotti’s a repellent punk and always will be. He’s a mean man. Whereas Persico—I mean, if we’re going to compare homicidal maniacs, Persico has every advantage …. He’s a man who felt there are things one does not do. One does not beat up a woman even to collect a debt.”

This ability to see a chivalric streak in even “Carmine the Snake” Persico is a reflection of a key Kemptonian concern: making distinctions among scoundrels. He has a remarkable ability to see the human virtues in those who are ideological enemies and moral pariahs to conventional liberals.

“I’m just sorry Roy was ever born. I’m sorry anybody that unhappy was cast upon the sands in America.”

There is Roy Cohn, for instance, with whom Kempton had a sporadic friendship and constant fascination. In a recent column Kempton quotes from a letter Fat Tony Salerno wrote to him. Fat Tony, displaying the courtliness Kempton prizes in these guys, introduced himself by saying, “Roy Cohn always stated that you were an honorable man.”

I ask Kempton what his assessment of Cohn is now.

“I never got over my ambivalence about Roy …. The world is full of people who are torn between the need to be loved and the need to be feared. Now, usually, really bad guys settle for the need to be feared. I mean, if you didn’t like Jimmy Hoffa, he set out to scare you. There are guys like that. But Roy never made peace with those two impulses, never discarded the desire to be loved …. You know what baffles me? I don’t know what people want out of life. More and more, I don’t understand what people want out of life. I don’t know what Roy wanted. He obviously wanted experiences of danger where there was no peril …. But I’m just sorry Roy was ever born. I’m sorry anybody that unhappy was cast upon the sands in America.”

There are, however, certain figures Kempton finds utterly without the redeeming virtues of mere scoundrels. These he calls “muckers.” Every once in a while he’ll write a column finally reading them out of his life because they’ve offended his sense of dignity too gravely. He did this last fall to Ed Koch. The occasion was Koch’s gloating, graceless post-World Series comments upon winning his bet with the mayor of Boston and demanding that Boston city hall fly the New York Mets’ flag. “Boston today is a city in subjugation,” Koch exulted with the overdramatized glee of the ersatz fan.

Kempton found it a sickening spectacle, an offense to the glory and dignity of the athletes of both sides in that beautiful seven-game struggle. Kempton’s farewell to Koch is a magnificent display of eloquent rage:

‘‘He has made his duties subordinate to his vanities; he has bullied the ill-fortuned and truckled to the fortuned; to walk in his wake has been to stumble through a rubble of vulgarities and meanness of spirit.”

But this last act, seeking to make the beaten but heroic Boston grovel, is just too much:

“The mayor has become a piece of civic property of whom we can no longer speak without apologizing to our fellow countrymen. Still it remains possible to pity him a little. He does not know what it is like to be Pete Rose in the 1975 World Series and go to the dressing room after Carlton Fisk has beaten you with an extra-inning home run and say you don’t care who won because it is simply an honor to have played in a game like that one.

“Koch may not care to learn how a gentleman bears himself from examples like Pete Rose’s, but there are many—most, I think—New Yorkers who have profited from that lesson and we are not in the main muckers. Still we can hardly acquit ourselves of all the fault in the possession of a mayor who is irretrievably one.”

Another personage Kempton finds utterly without redeeming ambivalences is City Comptroller Harrison Goldin.

You reserved some of your most intensely distilled anger for your last column on Harrison Goldin. What is it about him that so particularly arouses this feeling? I ask him.

“Well, for one thing, he’s just an awful guy …. I don’t write about Goldin anymore, because my theory is that when you really get to dislike a man that much, you shouldn’t write about him. I mean, a scoundrel without dignity will—I mean, I’m sorry to say it, but they are the ones who simply do not finally justify writing about.”

“Your best columns often are ones about scoundrels with dignity. I’m thinking of the ones on Carmine Persico and Stanley Friedman. [Democratic party big shot who became embroiled in the city scandals of the ’80s] What is it about scoundrels with dignity that—?”

‘‘Maybe it’s not the scoundrel. Maybe it’s the dignity I’m celebrating wherever it may happen to exist. It’s not a matter of condemning or not condemning scoundrels …. It’s how people act when the worst things happen to them.

“I mean,” he continues, “I wouldn’t call myself a connoisseur of rascals. I’ve known lot in my time and I’ve learned a little bit about how to calculate them …. I’m not sorry for Stanley. I’m sorry about Stanley.”

What was it about his scoundrelhood that appealed to Kempton?

“I don’t know. It’s very funny. I never in life have seen a job that was perfectly awful and disgusting and degrading that didn’t have a good man engaged in it …. There are a lot of rotten jobs that men can fall into at an early age, and when the time comes, when they’re caught, they’ll act decently. You know, it’s probably the good man in the bad job who’s my favorite subject.”

“Bigotry is not prejudice; it’s a commitment to erase from the face of the earth people that you don’t happen to like.”

He talks about making distinctions in the kind of corruption one encounters in the city. Worse than the Stanley Friedman bribe-corruption scandals, he feels, are the investment-banking scandals: “At least, at some point, somewhere down the line, there has to come a time when there is a product, that computer they were paying everyone off to finance, while insider trading produced no useful product but paper.” And even lower than the investment-banking scandal is the scandal in the Seventy-Seventh Precinct where cops were taking money to protect crack dealers.

“It took me a while to discover this,” he says, “but the biggest mistake you can make is to follow your ideas to their logical conclusion. That’s the only real mistake you can make with assurance. You can make a lot of others, but every now and then you can be right. But when you follow your ideas to their logical conclusion, you are always wrong. The cop who says to himself, ‘Well, if I’m taking money from the numbers runner, I might as well take it from the street dealer,’ has followed his ideas to the logical conclusion …. But there is a fundamental difference in the kind of corruption that appalls me when people ignore it. It’s scary.”

Scary?

“Scary when any society loses all sense of comparative decency. What’s the moment between Pollard giving secrets to the Israelis because he is intense in believing in Zionism and the moment when he takes the money for it? What’s the difference? What’s the difference, when you take the insider-trading cases, between the time when a guy says, ‘I need this to keep my portfolio up for the office,’ and the moment when he goes into a business as a tipster for Boesky? … There is a difference. I can’t say what it is, and what fascinates me is why doesn’t anyone know the difference? I mean, were there some high tribunal to judge the sins of journalists, I can assure you that there would be a number of things that I’d have to say: ‘Well, okay, I did it; I thought it was right at the time.’ But how can anybody think that selling crack on the street is right at the time?”

And, speaking of investment bankers and crack dealers—I ask Kempton about a column he’d written a few days earlier in which he took Mario Cuomo to task for a speech he delivered to a group of investment bankers. Cuomo’s flattering platitudes, Kempton said, failed to hold their feet to the fire or even take note of the current scandals.

Kempton says Cuomo called him up to protest that column: “He was complaining that I didn’t give his investment speech enough credit …. I get postcards from him all the time saying, ‘I’m glad to have you around to straighten me out or to tell me what I ought to do.’ But then he goes back and does the same thing the next day. He just doesn’t understand.”

What is it he doesn’t understand?

“Well, I vastly like him … but I have a theory that the trouble with America is we don’t have a Whig party. When we made the president of the United States king, in some curious way… if everybody was open to running for king … the job [that] people closed off was the opposition. I mean, if you could be king, why belong to the opposition? So no one in America has ever understood, in my lifetime, at least, the role of the permanent opposition. If you take Burke and Fox, neither of them could ever be king; consequently they were able to carve out a position. They managed to make this position of being the voice of reproach, what the Whigs used to call ‘the good old cause.’ If Cuomo decides not to run for president, then the other job open to him is to represent the good old cause …. Cuomo doesn’t understand that. He doesn’t know the specific …. And you’ve got to get off abstractions; you’ve got to think about people. The greatness of Burke was that whenever he was abstract, he was always shit. Whenever he was concrete and talked about real toads in real gardens, he was wonderful. Cuomo doesn’t understand that. You could go through your life, you can end up—if you understand the idea of opposition, you can be Norman Thomas. Is that so bad? You’re not president of the United States. A few people will remember you for what you were. He doesn’t understand that.”

An example of the kind of real toads in real gardens Kempton feels Cuomo fails to understand is the Mary Beth Whitehead case. [Whitehead was the surrogate mother who decided she wanted to keep her child, rather than give it to the parents who contracted for it.] Kempton was, I believe, the first reporter to publish the actual details of the Whitehead contract—the mandatory abortion requirement and other barbarities. He’s been witheringly scornful of the way the natural mother has been treated by the courts and the lawyers for the Sterns because of her inferior-class background.

“Cuomo is so messed up,” Kempton says, “with getting perfectly ready to walk down in St. Patrick’s Cathedral and nail up the ninety-five theses on the wall that he doesn’t understand that’s not what it’s about…. One of my few virtues is that I find something totally fascinating every three weeks, but this happens to be it. And Cuomo doesn’t know, he doesn’t react. I talked to him on the telephone yesterday and he was kind of complaining. And I said to him, ‘Do you understand that to you the Catholic Church is as bad as it is to Jerry Falwell?’ I mean, you know, every now and then they’re right. And this was what Cuomo could be talking about. I mean, he talks about values and why the four children committed suicide in New Jersey …. I’m angry with him; I’m sorry to say it. I’m very angry at him because I think he should understand these things and say them …. If a politician is not campaigning for something, then I think we ought to ask him to talk about choices that a society might make, and he’s not doing that.

I ask Kempton, as a connoisseur of scoundrels, what he thinks of the city’s chief scourge of scoundrels, Rudy Giuliani.

“I think he’s a bigot.”

A bigot?

“A bigot. I don’t mean he hates Jews, Negroes, or Italians. I mean, bigotry is the feeling that people need to be hounded off the face of the earth. You can be a bigot if you’re a liberal and you’re talking about the Republican leader of the House of Representatives. Bigotry is not prejudice; it’s a commitment to erase from the face of the earth people that you don’t happen to like.”

He cites Giuliani’s most recent series of indictments (of Bronx congressman Mario Biaggi, and Brooklyn boss Meade Esposito, and of Bronx Borough President Stanley Simon) as examples of prosecutorial zealotry exceeding the bounds of reason.

“Stanley Simon … strikes me as the American Dreyfus,” he says, laughing. “These aren’t scandals. You know, Manes is a scandal, Stanley Friedman is a scandal … but a guy getting a job for his brother-in-law?”

Among current corruption prosecutors, a breed of whom he’s evidently not too fond, Kempton expresses a marginal preference for Brooklyn’s Diane Giacalone, John Gotti’s prosecutor.

“When I first met her, she said to me, ‘Are you going to compare me with Robespierre?’ So I said, ‘What do you mean?’ And she said, ‘When you called Rudy Giuliani “a sea-green incorruptible.” ‘ Now, what fascinated me was, how did she know where that came from? I mean, this is a city of eight million people. There could be no more than twenty who ever read all the way through Thomas Carlyle’s French Revolution, which, by the way, is the most from wonderful book I’ve read in years. Anyway, she knew where this remark came from … Now, if you say to Giacalone, ‘I think the witness you’ve served up is absolutely repellent to every civilized man,’ she will say, ‘All right, but where else can I get a witness?’ But if you say to Giuliani—I remember, he said to me during the Friedman trial, ‘What did you think of Lindenauer?’ And I said he was so awful that I had been saving a line for ten years, and that was, ‘I have read Louis-Ferdinand Céline and I have communed with Roy Cohn and I will say to you that he is the worst ambulant creature that I have ever seen. Period.’ Now, I’m not proud of that line because it’s stolen from Disraeli, who said of somebody, ‘I have known Bulwer-Lytton and I have read Cicero and I will tell you that he is the most conceited man I have ever known.’ Giuliani said to me, ‘How could you say that? He [Lindenauer] is very sorry for what he did.’ Now I’ll give Giacalone one credit. She knew these guys weren’t the least bit sorry for what they did. They were in a jam; they turned in their friends. But Giuliani believes this, he really does believe in the shriven soul, in the penitent. Such men pile the faggots under the feet of anybody who comes in their path.”

Would you say he’s an example of someone who follows his ideas to their logical conclusion?

“He’s ‘a sea-green incorruptible,’ ” Kempton says, returning to Carlyle’s phrase for Robespierre. “I just don’t like him. I don’t like his pale face, his pale eyes. And I don’t like him. I don’t think anybody goes to glory if Giuliani wins a case.”

Since Kempton is quoting historians, I decide to ask him if I was right in thinking Gibbon was his stylistic, if not conceptual, model. “I don’t write like Gibbon,” he says. “The models that move me most—the prose that touches me most is not eighteenth-century prose but seventeenth-century prose. I mean, it would be ridiculous to say that Clarendon’s History of the Rebellion is better written than The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Well, nothing is better written than The Decline and Fall, except possibly Gibbon’s autobiography. But there is a line in Clarendon that I don’t think Gibbon could have written, and it does define what I would like to do. Do you know anything about Clarendon?”

Clarendon that he found most resonant with his own work.

“[Lord Clarendon] said that his purpose was ‘to appeal, if not to the conscience, at least to the curiosity of mankind,’ And I thought that’s what I’d like to do.”

I confess my ignorance and Kempton fills me in on Clarendon, a man who, in the course of shifting allegiance during the civil wars of the mid-seventeenth century, unfailingly chose the losing side.

“He was a man named Edward Hyde who went into exile in opposition to Cromwell. Then he became lord chancellor for Charles II after the Restoration, and he became Lord Clarendon, and then Charles II couldn’t stand him anymore and he threw him out. He was always on the losing side, but he was a towering spirit. I once called [William F.] Buckley because he had this great connection with [publisher] Henry Regnery. And I said, ‘You know what I’d like to do? I’d like to spend about six months and do a series of books that were histories of revolutions by the losers. Well, my losers. I mean de Tocqueville in 1848, that’s a loser. And one was Clarendon.’ And Bill said, ‘I’ve never heard of Clarendon.’ ”

Kempton returns to the lines in Clarendon that he found most resonant with his own work.

“There are two lines in it that I’ve never forgotten, that stuck in my mind. In the introduction to his book, he said that his purpose was ‘to appeal, if not to the conscience, at least to the curiosity of mankind,’ And I thought that’s what I’d like to do.”

And what was the other line from Clarendon he found so memorable?

“There was one sentence in which he said, ‘There is the whole finger of God in these events.’ Now, you know Gibbon wouldn’t have done that. I mean, Gibbon, you know—what’s the point of The Decline and Fall except that people who act as though there were such a thing as God are out of their fucking minds? Which is why I like the seventeenth century. I mean, the idea of ‘the whole finger of God,’ the idea of finding the finger of God in events.”

Kempton makes himself sound like a lapsed Episcopalian (“I haven’t been in a state of grace for many years” is the way he puts it), but every so often in his columns, the faith makes itself felt. [In fact, despite his misleading modesty about his state of grace, in the last decade of his life (he died in 1997) he was a faithful churchgoer.] When he spoke of the finger of God, I immediately thought of an uncharacteristically direct example of this: Kempton’s column last spring about Bishop Tutu. It’s one of the most simple and powerful pieces of inspirational prose I can recall reading, daringly naked in its soul-baring emotional appeal. I remember beginning to read it on the West Fourth Street subway platform and finding, by the time I finished, my eyes blurred so much I couldn’t tell if the incoming local was the K or the E. I tore it out and have carried a yellowing copy of it around with me for nearly a year now.

When I ask Kempton about that column, he dismisses it as nothing special. And on the surface, its subject is slight. Its subject is Bishop Tutu’s silliness; at least, it begins with that.

“The most touching thing about Tutu to me is that he is so ridiculous,” Kempton tells me. “He is probably the most ridiculous great man I have ever seen. I mean, he’s a dithering Anglican bishop from Masterpiece Theatre. I mean, you expect whenever you see him to have Alistair Cooke explain to you that this curious sort of phenomenon existed in Barchester Towers at one particular point The giggling that goes on. And that’s what makes him so moving.”

Somehow Kempton’s column manages to capture the silliness and the heroism, and the fulcrum of it is his evocation of the power of fear.

He quotes Tutu telling his Wall Street congregants: “God has set His church, weak, and vulnerable, and fragile as we are, between South Africa and disaster …. ‘Ha, ha,’ God has said to us, ‘you guys in South Africa are going to help Me liberate South Africa.’ ”

“Man’s recent history,” Kempton writes, “however otherwise graceless, has been wonderfully graced by churchmen—by the homely Tutu in Cape Town, majestic Wyszynski in Poland, the subtle Sin in Manila, the murdered Romero in San Salvador, each interposing in his different fashion the reproach of eternal good to transient evil.”

And then, two paragraphs later, Kempton does something I’ve never seen him do before. He shifts abruptly from prose to a kind of heightened preaching. The text of his sermon is fear.

The lives of these churchmen, he writes

instruct us to cast away fear ….

Fear is the infection that sets us ravening and quavering.

It is to the god Fear that we bow down when we pop pills or drink ourselves numb … and yes, when we worship the gun.

And Desmond Tutu travels about, not so much defying, as laughing and almost dancing in the shadows of his peril.

No guards surround him, no guns shield him, he is naked to every wind and missile of malice; and he tells pawky little Episcopal jokes and chuckles while he implores ….

Lives like his are our redemption, not because they make us holy … but because they can teach us to be unafraid.

When I ask Kempton what was responsible for this uncharacteristically direct and heartfelt inspirational shift, he tries to dismiss it.

“I don’t know. Maybe I had nothing to write that day and I was straining …. There’s always a moment when you get into the middle of a piece that is explained not so much by divine inspiration but the fact that you’ve run out of quotes from the other guy.”

Yes, that’s true, but it is also at those moments that—with the mask of the quotes from “the other guy” removed—the true face of the self may be most truly revealed. The Episcopal Church lost a brilliant inspirational preacher when Kempton fell from grace to become a newspaper writer.

For he is capable of seeing in the meanest of human impulses the fingerprint, if not the finger, of God. For me, the most inspirational moment in my conversation with Kempton came at the very end of dinner, his response to my final question to him. The subject was the perennial American and tragedy of race and its most recent manifestation in Howard Beach. [The predominantly white neighborhood in Queens where a bat-wielding gang of white youths chased a black teenager onto a highway, where a car struck and killed him.]

I ask Kempton if he is gloomy about the future of race relations in the city, and he invokes Menachem Begin as a source of inspiration on the subject.

“I’ve always been gloomy, I think, about what I guess I would call the failure of the sense of community. You know it’s very strange …. If you can get this into the piece, it’s the only wisdom I’ve learned …. There’s only one man I’ve ever met in the course of my entire existence who I thought had a very clear sense of what a community means, and that was Menachem Begin, whose feeling was, if you’re Jewish, there’s nothing that you don’t deserve—whether you’re Sephardic or Ashkenazi, it makes no difference …. If you’re Jewish it’s enough…. Now, granted, he didn’t extend this view to all humanity. But to begin by saying, ‘If you’re Jewish it is enough,’ is something. And the thing that—I wouldn’t say it breaks my heart, but certainly abrades it considerably—is that with all our quarrels in the United States, nobody ever says, ‘If you’re American, nothing is too good for you.’ … Very few of us understand it. Very few of us understand that Michael Griffith [the Howard Beach murder victim] … standing in that place was someone to whom, as an American, we owed something. I guess maybe there’s something about being Southern and race that goes to that. It is always a feeling inside, awful as it was, that we’re all Southerners …. There was a sense of recognition, if you were both lost in the North together—colored guy or yourself—you were both Southerners. It’s insular and it’s regional, but I don’t think you can have a sense of brotherhood and humanity unless you first have a sense of insularity.”

[Photo Credit: – Library of Congress. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection]