The Sound: A tight, simple rhythm, pulsing, throbbing. A smooth, cool guitar lightly plays a handful of notes, but just the right notes. The feel is subtle, complex; a combination of what is right about jazz, what is right about soul and what is right about pop, with none of the excesses. Then strings: soaring, lush, romantic. And horns suddenly slip in with staccato notes: Ta-Ta-TA, Ta-Ta-TA. “Whut they doin’?” three husky, tough voices shout in unison, and then the same three voices switch to a resonant three-part harmony, their sound sweet but full, their words bitter, hard.

“They smile in your face,” they croon. “All the time they want to take your place … the Backstabbers.” A synthesis of contradictory musical styles that have never before met in the same song, each playing counterpoint to the other for a hot, live sound, a joyful noise. A sound, The Sound of Philadelphia. Black music so powerful and fine that even whites had to dance. But now the sound is gone.

The Sound: A cool, quiet spring night. A green Rolls-Royce screeches down deserted, curving Lincoln Drive, a road too full of twists to be the major thoroughfare it has become: a stretch of highway that is dangerous even at 25 miles an hour, the legal limit.

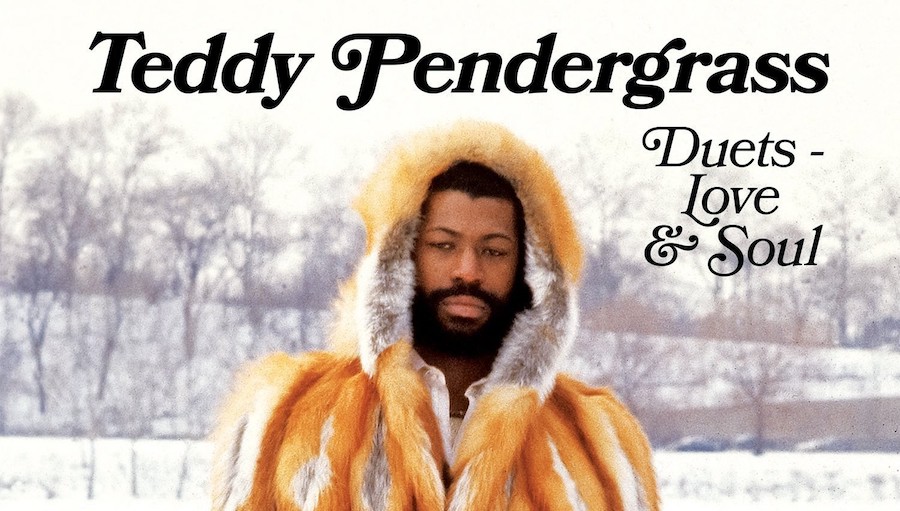

Coming out of one sharp turn, the car swerves against the concrete median, ricocheting off into a pair of trees. On impact, the car roof buckles, the front windshield shatters and the entire driver’s side of the vehicle is smashed. Inside, Teddy Pendergrass, the last great singer to embody the sound, The Sound of Philadelphia, lies with his head cradled in his passenger’s arms. The singer is barely moving; one of his eyes flutters open and closed. As it happens, the first car to approach the scene is that of a disc jockey from a black music station that rode the wave of The Philly Sound. According to the police report, the first thing out of the DJ’s mouth when the ambulance arrives is a line from an old tune by the Spinners, a group that floundered in the ‘60s only to come to the Philadelphia hit factory in the ’70s and attain stardom.

“What goes around, comes around,” the DJ says.

The Way the Music Died

There were ten years between those two sounds. “Backstabbers,” the tune performed by the O’Jays in 1972, was the first big hit produced by Philadelphia International Records, the company that created The Sound. Philly International was an independent record label based in Philadelphia but financed and distributed by CBS Records in New York. The label was built around the creative talents of its owners, Kenneth Gamble and Leon Huff, local boys who had made good nationally. A string of smash records followed “Backstabbers.” By the end of 1972, Philly International was being hailed as the most exciting thing happening in American music—black or white. The label was manufacturing “crossover” hits: songs that were No. 1 on both the black and the white charts. In less than nine months Philly International had sold 10 million singles and nearly 2 million albums. Over the next few years, the company’s roster grew to more than 15 different acts, and the family of producers, writers, arrangers and musicians who made the music had covered their walls with gold records and filled Gamble and Huff’s pockets with millions and millions of dollars. When the musicians and producers weren’t making records for Gamble and Huff, they were marketing their Philly Sound to artists from around the world who wanted it. But the musical family didn’t make house calls—if you wanted The Philly Sound, you had to come to Philly. And the music business came. The headquarters at 309 S. Broad Street became a hit factory; the Sigma Sound Studio on N. 12th Street, where the songs were taped, became a 24-hour-a-day music-processing plant. By the mid-’70s, the label was the second-largest black-owned company in the country, grossing $25 million to $30 million a year.

Then the company began to suffer a few setbacks, minor at first. One was a payola indictment that rocked the record industry. In 1975, Gamble and Huff were indicted for doing what many people say every major and minor label in the country has always done to get records played—paying off radio disc jockeys. It was like indicting a basketball player for throwing elbows. But the case against Gamble was settled with a no-contest plea and a small fine. The charges against Huff were dismissed.

When Teddy emerged from the hospital, his spine patched with a bone graft from his paralyzed right leg, his voice temporarily out of commission and his image tarnished, the music world suddenly realized that Philadelphia International Records had disappeared.

Then, some of the original acts began deserting the label. The big-hit Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes split up because their lead singer, Teddy Pendergrass, wanted to become a solo artist.

A new era was beginning. Once, groups like the Blue Notes and the O’Jays performed tunes so heavy with lush orchestration that some people joked that Mickey Mouse could have done the vocals and still gotten a hit. Now the superstars were moving in: the scope and vitality of the music had narrowed to leave room for the personality of the new performers. Less crossover, but still a lot of record sales. Teddy Pendergrass, then 26 years old, became a huge success with his strong sexual aura and gospel preacher’s voice. A singer named Lou Rawls, who had some hits in the ’60s but whose career seemed at a dead end, came to the label and emerged with a new image and a new set of tunes. The stable of secondary performers grew less notable, but the big names were still generating plenty of cash for the company.

By the ’80s, when the record business began experiencing a deep nose dive along with the rest of the economy, Gamble and Huff still looked like they had a recession-proof investment in Teddy. Recording-industry insiders figured that Gamble and Huff would ride out the economic ripples with steady Teddy and then come up with a new star to replace him—as he had replaced the original cast of The Philly Sound. Teddy’s crash came in 1982, putting the brakes on a career that had included dozens of hit records and stage shows that sold out only minutes after tickets went on sale. But when Teddy’s fans—many of them women attracted by his sexy lyrics and sexier style—read in the papers that the singer’s passenger on the night of the crash had been a transsexual with a long record of prostitution arrests, they were shaken. When Teddy emerged from the hospital, his spine patched with a bone graft from his paralyzed right leg, his voice temporarily out of commission and his image tarnished, the music world suddenly realized that Philadelphia International Records had disappeared. It was only Teddy’s record sales that had maintained a smoke screen over the crumbling company. Word spread in the industry that the four albums Gamble and Huff owed CBS were very late. By last summer Philly International had laid off half of its staff. The few artists remaining were looking for new record deals, and Gamble and Huff were trying to get out of their contract with CBS. There was talk of dissolving the partnership. Philadelphia International Records, the company that produced The Sound that the world once couldn’t get enough of, had indeed fallen along with the rest of the record business. But the big companies like CBS had merely to cut back to meet the recession. Philly International had, for some reason, self-destructed.

The Search for the Sound

On the phone from his New York office was Nelson George, who covered black music for Billboard, the music industry’s most influential periodical. Today he wasn’t coldly discussing music-business nuts and bolts. When Nelson spoke of Philly International and The Philly Sound, there was a sadness in his voice. “It’s really a tragedy,” he said. “They were among the most powerful entities in the business, and, more important, I loved their music. Since their demise the whole Philly music scene is dead.”

“What happened?”

“I’ve heard a lot of things. People said that Gamble had a messianic streak, that success had overwhelmed Gamble and Huff, that their staff felt alienated and misused, that the company’s ideas were just too ambitious. But nobody I’ve talked to really knows what happened. They just know a place where a lot of music was made isn’t making music anymore. If you find out what happened to Gamble and Huff, I’d sure like to know.”

I hung up the phone and looked over at the small pile of cassettes in the corner. Fishing through the clacking mound, I found a tape I had made years ago: fast, hot music that kept me awake when driving or psyched me up when I needed it. I looked at the song titles and the artists’ names. Some of the tunes were from Motown, the Detroit black music factory that, in the ’60s, had churned out hits by the Supremes, the Temptations, the Four Tops and Smokey Robinson and the Miracles. But the bulk of the tunes had been recorded by Philadelphia International Records or had been cut here in town.

Gamble and Huff (along with Thom Bell, an independent producer who had grown up with Gamble, produced acts like the Spinners and the Stylistics and was a business partner in the company’s publishing arm, Mighty Three) had been responsible for many of the major soul, pop and disco sounds of the ’70s. But even before The Philly Sound became a legend, Gamble, Huff, Bell and the corps of local musicians who became their studio mainstays had been responsible for dozens of ’60s hits: “I’m Gonna Make You Love Me” (a hit by the Supremes), “The Horse” (a hot instrumental that is still a soulful warhorse of marching bands everywhere), “Brand New Me” (the tune that saved Dusty Springfield’s career in 1969), “Expressway to Your Heart” (the only pop hit ever inspired by the Schuylkill Expressway), “Love Is like a Baseball Game” (remember … “three strikes you’re out!”) and “La-La Means I Love You” (the Delfonics hit from 1968).

There was something indelible about all these songs to me, something stronger than a nostalgic tune triggering a forgotten smile. This music had made a difference in my life. It was the music I had listened to in my living room while practicing dance steps: a tall, clumsy, very white guy hoping to look like one of the Temptations by Saturday night. There was something that had made me stop whatever I was doing and sing along when the orchestra abruptly halted and Billy Paul’s voice just sailed and moaned without accompaniment, “Meeeeee, aaaahand Missus, Missus Jones!” Kenny Gamble had been fond of saying that there was a message in the music. But listening to the tape again made me realize that there had been far more than that. There had been magic. But, the magic show was over now, and the Billboard guy wasn’t the only one who wanted to know why.

What Color is the Music?

My first call was to David, a 30ish antiques dealer I knew who was among a growing group of music-industry burnouts who had fled the relatively sleazy New York record scene and started their own businesses. We started talking about why Philly International had been such a phenomenal success.

“Gamble and Huff had something that made their records sell and sell,” David told me. “You know, there’s a big difference between a turntable hit, one that gets a lot of air play, and one that sells in the stores. Philly International records sold. And a big reason was Philly itself. Philadelphia is the top music city in the country. The fans here are so critical and discriminating—they even boo Santa Claus. So Philly is a good barometer for the rest of the business. And Gamble and Huff had good relations with those influential Philly jocks—they had grown up with those guys.”

David suggested I get in touch with Greg Hall, a friend of his from the record business who now did independent music production and cable work. Greg was black, which David wasn’t, and was more in touch with the black community in Philly. “After all,” David said, “the key to figuring out Gamble and Huff isn’t just the music business. You know about the label because of the songs that crossed over. But it’s getting inside the black music business you should be interested in, and all the racial problems in Philadelphia are right in the middle of it.”

I met Greg Hall in a Chinese restaurant in center city. Greg now hung out with the jocks, mostly Sixers players, but he had a good set of roots in the black music business. He had worked for a black-oriented jazz record company and was close with Miles Davis, another Philadelphian. Greg had once done a lengthy, controversial interview with the normally close-mouthed trumpeter fordown beat, the jazz magazine. He also knew Kenny Gamble, although it was clear they were no longer close. “We go back to junior high school, 1956,” Greg said. “I remember him singing in the bathroom at Sayre Junior High.” Hall was an intense, intelligent man but was also bitter; in part because the big money in the record business had eluded him. There was that, and there was the racial thing, too. Greg Hall spoke of the blatant racial divisions in the music industry—and in the press and in the world, for that matter. Being white, I felt slightly chastised.

Though nobody suspected Gamble and Huff of being involved in illegal activities, investigators surmised that the pair had been forced to deal with the black mob, and possibly the Cosa Nostra to get their records made and distributed.

“They used to call the music blacks made and listened to ‘race music’,” he told me. “That was until the record companies became aware that there was a black market. Then the white companies went in to exploit those markets, which is fine, but they never gave the blacks who were being used to exploit the markets a fair deal. Motown was owned by a black guy, but it was basically a white deal. Kenny Gamble rose at the right time in black politics. His music was involved in a whole movement that alerted a race that they had value, telling blacks that their businesses could survive. He prospered, and that’s something that bothered the white establishment. How did you get over that fence, the white guy wants to know. He can’t figure it out because he knows how high he built that fence.

Hall was also aware of how little access to the media blacks actually have—especially in a town like Philadelphia. “You rarely see a story about black people unless there’s a crime involved or Teddy crashes,” he said. “If [prominent black DJ] Georgie Woods gives out $50 and $100 bills to poor people—black and white—waiting in welfare lines, you don’t see it in the paper. But if Woods does something wrong, it’ll be on the front page.”

Hall wished me good luck in my research but warned me that Gamble and Huff weren’t likely to speak with me. They had been burned by the media before—really got grilled on the payola thing. Before then they had been merely reluctant to speak with the press: Huff was a very quiet guy to begin with and Gamble usually spoke in religious jargon, like Ali after a fight. Now that their business was on the ropes they weren’t likely to talk to me: entertainment types don’t speak up unless they have good news.

The bad news they might not have wanted to discuss went deeper than payola. Law-enforcement officials said that Philly International had been under investigation for years for its links to the “black mob,” in part because its artists occasionally performed at functions with heavy black mob overtones. Another reason the FBI was investigating was because the black mob controlled the cocaine market in Philadelphia in the ’70s, a market not unknown to many musicians and other entertainers.

In 1977 law-enforcement concerns about black mob interaction with Philly International were heightened. Late in 1976, Teddy Pendergrass had announced that he would leave Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes to go solo. Taaz Lang, Teddy’s girlfriend, stepped forward as the singer’s new manager. Her good fortune was reported in a now-defunct black magazine called Philly Talk under the prophetic headline NUMBER NINE WITH A BULLET—“bullet” being Billboard chart jargon for a hot record. Four months later, Taaz was gunned down in front of her home on Allens Lane in Mt. Airy. Investigators believed the unsolved murder was a black mob contract hit—the reasons why had remained unclear. Some said Taaz had owed the mob money for drugs. Others said the mob had wanted her out of the way so they could control Teddy. True to form, the murder had received very little play in the major papers—after all, it had been a black murdered, not a black arrested for murder. This lack of media coverage could well explain why, when the Daily News ran one of their “turn in the killer” contests six years after Taaz Lang was gunned down, not much progress had been made on the case. If the white papers weren’t interested, the black mob—or somebody—clearly was interested in Teddy. Eighteen months later his New York agent was also shot—also a contract hit. The attempted homicide remained unsolved but one angle the New York police pursued was the possible link with Teddy.

Though nobody suspected Gamble and Huff of being involved in illegal activities, investigators surmised that the pair had been forced to deal with the black mob, and possibly the Cosa Nostra, too, to get their records made and distributed. Organized crime has long been alleged to have infiltrated the entertainment business. Dealing with these people was simply the way business got done. Payola, the practice of paying radio-station personnel for playing certain records—was the same thing. Everybody had done it. According to some insiders, Gamble and Huff had probably done it less than most. Gamble had a reputation for frugality. Some suspected his cheapness had brought on his 1975 indictment in the first place. If paying off DJs was defrauding the public, why hadn’t any radio personnel been indicted? Hadn’t the DJs, whom the government had caught in the act of being bribed, defrauded the public as well? The deep suspicion in the industry was that Gamble had been indicted because someone hadn’t been paid off.

There obviously had been something screwy about the indictment, because the government had let off Gamble and Huff awfully easily after two years of investigating. After plea bargaining and a no-contest plea by Gamble, relatively small fines totalling $40,000 were slapped on Gamble and a handful of his employees.

The only regular local coverage of the multimillion-dollar black record company and its ups and downs appeared in a little column in the Daily News by someone named Masco Young. Young had written insightfully about the black music business. He had been the only reporter in town to observe that with Teddy gone, the record company that had once brought millions of dollars into Philadelphia was little more than an empty building on South Broad Street. In the midst of constant caterwauling about the flight of business from Philadelphia, the white press had virtually ignored one of the biggest business stories in town.

Masco Young was a black entertainment reporter—once syndicated nationwide—who had been hired by the News to write what seemed an awfully blatant example of journalistic apartheid, a column only about blacks. He had written with candor but clearly seemed to know more than he had been given space to write. I called him.

When I met with Masco Young, he said he had first known Gamble through the singer Dee Dee Sharp. Sharp had been one of those teen phenoms: she had answered a newspaper ad for a girl who could sing and play piano and ended up cutting a record with Chubby Checker. The session had been at Cameo-Parkway Records, a Philadelphia record company that in the early ’60s had been what Philly International would become in the ’70s—a hit factory. Dee Dee became a star with a silly hit tune called “Mashed Potatoes.” Eventually, she toured the so-called Chitlin Circuit with the other popular black acts of the day. Kenny Gamble was sweet on Dee Dee. In 1967, they were married.

Young recalled Gamble as an easygoing, quiet kid who acted more like a professor than a musician. But his business acumen had always been evident.

In the early ’60s Gamble was trying to get Cameo-Parkway to produce his stuff and was becoming something of a pest to owners Bernie Lowe and Kal Mann, who often had him tossed out of the offices. The building that had housed Cameo-Parkway, Young pointed out, eventually was bought by Gamble. It became the home of his Philly International Records. “What goes around, comes around,” Young said. There was that phrase again, the phrase from the police report. I scribbled it down for the second time and let Masco Young continue.

“Kenny was a genius, he was phenomenal at bringing out songs and matching songs with artists.”

Gamble owned a record shop on South Street before he started making records. That’s how he met Ben Krass, owner of Krass Brothers and an early investor in Gamble’s record projects. In the mid-’60s, Gamble was learning both sides of the record business—writing songs and selling records. He was learning the rules of the game. “He learned that to get your records played, you had to give up a little action,” Young explained. “He learned that there were certain artists that certain promoters weren’t allowed to book because of deals. If the artist agreed to perform for any promoter besides the powers that be, his records wouldn’t get played on the air.”

Masco Young said he had been wary of speaking to Philadelphia Magazine. He feared a white press was out to do a hatchet job on Gamble and Huff. Eventually, though, he became convinced that I was truly interested in finding out what had really happened. He decided to help. He put me in touch with a grocery list of sources. The first was Weldon McDougal III, a former promotion man for Gamble and Huff.

The Highs and Lows in a Singer’s Life

Weldon McDougal was 46 years old, owned a small home in Lansand was holding on the record business for life. His walls were decorated with gold records; the titles were a partial catalog of the great black hits of the ’60s (when he had worked at Motown) and ’70s (when he had worked for Gamble and Huff). Weldon had never made the big bucks in music, but he had been around the Philly music scene since the late ’50s, and his long experience had kept him employed … albeit sometimes employed by old buddies who had left him in the dust on their way to the top. He had fronted his own group called the Larks in 1960; the group had broken up later, but Weldon could count among his accomplishments the fact that the Larks’ backup band, whom he had chosen, had ten years later become the backbone of The Philly Sound, the orchestra that called itself MFSB. Besides performing, McDougal had worked as a doorman for American Bandstand, the TV dance show that brought the Philadelphia music business its first black eye—a 1960 payola scandal not unlike the one that would hit Philly International in 1975.

McDougal had scraped around in the early ’60s like every other black musician in town, trying to write songs and get an “in” at Cameo-Parkway, which had become a national power. McDougal had also gotten an inside look at the two hottest hit factories of the past 20 years, Motown and Philly International.

“The public knows only the names of the artists,” he explained. “But the producer, like Kenny Gamble or Leon Huff, whose name is in much smaller print on the back of the record jacket, is everything! A producer really has to figure out how the song should sound, even how the singer should sing it. The artist doesn’t even have to be there as the sound is being created—that’s how little impact the singers have. They just have to show up and sing.”

McDougal had done promotion for Philly International during the glory years, 1972 to 1976. Then he had been let go from the company. He, too, sounded bitter.

“Kenny Gamble, to me, was a sleazy, rotten motherfucker,” Weldon said, matter-of-factly. “He always took and never put back. Look at the artists who became famous from the label. Where are they now? The acts Gamble had never ended up with nothin’.”

Weldon was also disgusted about the way drugs had infiltrated the record business. “Drug dealers got involved in the music business to the point where it was more important to hire a guy with an ‘in’ that was drug related than to hire a guy with good business sense. People in the record business weren’t dealin’ in records, they were dealin’ in drugs. So many guys were into cocaine. Kenny himself always stayed away from it. But a lot of guys around Kenny were into drugs.”

Weldon’s claims of drug abuse and insensitivity to artists’ needs set me thinking about one performer in particular, Billy Paul. Paul had won a Grammy in 1972 for his powerful ballad “Me and Mrs. Jones” and had then virtually disappeared from the charts, apparently a victim of poor song selection on the part of Gamble and Huff. Everyone I had asked about Billy Paul had responded similarly: shaking their heads and muttering, “That coke will get you every time.” But none of the people who had talked about Paul had seen him in years. I thought it might be good to find out if all the terrible things his old “friends” were saying about him were true.

I went through six phone numbers before getting one that rang in Paul’s house. Some had been disconnected, some changed. I finally reached the 45-year-old singer’s home and talked to his wife, who explained that Billy was in class just then and that he would call me back. He was taking music-theory courses at Camden County College. That didn’t sound like dangerous, irrational behavior to me, and it didn’t really jibe with the way Billy had been described: one source had warned me not to interview Billy, because if I wrote anything negative the singer would kill me. Unless doing homework set Billy on rampages, his “friends” had him all wrong.

Inside the Paul home in Blackwood, New Jersey, I was immediately taken by the elaborate Oriental artifacts Billy and his wife, Blanche, had collected. The Pauls seemed weary, scared in a way, but at the same time they appeared to have recently turned the corner and left bad times behind. It seemed that they had turned similar corners before with mixed results. Still, they had been married for 17 years, a long time for people in the record business. There was something strong between the two of them. But that strong relationship had obviously been tested over the years.

The Pauls were ready for the drug questions: it was all they heard these days, so they gave the stock answer. Billy was jogging a mile a day and taking classes in Camden; he was writing music and trying to get a new record deal; he was more fit than most 45-year-olds, and he challenged any of the younger musicians who had made the accusations to stay with him in a mile race. Did he look like a cokehead, he wanted to know?

No, he didn’t. But he had the hard, sad look of a man who was successfully but painfully getting past his past. He looked like a man with hope.

Billy Paul had bittersweet memories of his ten years with Philly International. Sweet beause of his one hit, but bitter because he felt his career had been mismanaged by Gamble. Billy Paul said he was the first victim of Kenny Gamble’s early black-power zeal.

“After ‘Me and Mrs. Jones’ we were looking for another single. My name was known to a large public, black, white, all over the world. The natural step would have been to pick a song with universal appeal. The only song I told Gamble notto release was called ‘Am I Black Enough for You?’, which I thought would turn off a lot of people. Gamble released it anyway. I guess he thought it was more important to use my fame to get the word out than to help my career. Or maybe he just thought that the black audience was more important than the whites who had loved ‘Mrs. Jones.’

“Whatever the reason, the song failed, and I never got back up to where I had been. We had good records, but no great ones. Then when Teddy Pendergrass decided to go solo, Gamble just began to ignore me—he chose Teddy over me as the label’s big vocalist.

“Gamble wasn’t keeping his eyes open to new trends in music. He was getting too wrapped up in running the business. There was a natural direction for me to take after the ballad thing had passed—I was originally a jazz singer, and jazz vocalizing was making a comeback. But nobody at the label thought of that direction for me. Al Jarreau is now a superstar with that kind of material. I do some of his songs in my act. If Gamble had been thinking about my career, I could’ve been Al Jarreau.”

At any rate, these days, Billy Paul was now performing out of the country. A veteran, Paul often did tours of Europe for the State Department, playing to American soldiers. He was making a living: the power of a hit like “Mrs. Jones” can be sustained for a lifetime. Billy was shopping for a record deal; he was doing okay.

When Billy left the house to go to a doctor’s appointment, I got a chance to speak with his wife alone. Blanche spoke in a voice that at some points was strong and at others came close to cracking. She had supported the couple with a dress shop when Billy’s luck was down; she had also owned one of a set of his-and-hers Mercedes Benzes when his luck was up. She admitted he had gone through a lot of drugs, as a lot of people in the industry had. That, she assured me, was all over.

When I returned to the office I realized the time had come to interview Gamble and Huff. My plan had been to do enough interviews with sources who had contacts at the label that the two would realize I was sincere and break their silence. I called their lawyer, Phil Asbury. He said he was sure that Gamble would speak to me, but that they were in the middle of important contract negotiations. Could it wait? I told him it couldn’t wait long. He said he would get back. He didn’t. Over the next two weeks I left a dozen messages a day for him and a similar number for Gamble, Huff and Earl Shelton, the man who administered their publishing company, which was still making royalty money as long as the old records were being played. What remained of the Philly International brain trust would simply not come to the phone.

The studio musicians were easier to reach. One who was eager to talk was Don Renaldo, a tough-looking, white Italian-American who played first violin in the MFSB orchestra and was the general contractor for the orchestra sessions.

Renaldo seemed to miss those years when the label was cooking. They had been unlike anything he had ever before seen as a studio player, he said. Most studio sessions were designed to run as efficiently as possible—the music was generally written out and each guy played his part precisely the way it was written. Quick and easy, especially since studio time ran $130 an hour, and each musician was making about $50 an hour with a three-hour minimum. But Gamble and Huff had done things differently. They would come into the session two hours late, with a tune, the lyrics and some ideas and then let the musicians themselves get involved. Much had been done on instinct: Gamble couldn’t read music well so he hummed what he wanted the players to play. For the studio musicians, whose egos had usually been submerged beneath whatever drivel they were being well paid to play, working with Gamble and Huff was a creative bonanza. They rose to the occasion, many of them for the first time in their professional careers, feeling like musicians instead of mere technicians. With Bobby Martin doing arrangements, Gamble, Huff, Bell or Bunny Sigler producing and a group of local studio guys who had been playing together all their lives finally getting a chance to let loose, it was no wonder that the music had been so hot, so sparkling, so tight. The feel between the musicians was so strong that they didn’t even need vocalists to make hits. Dubbing themselves MFSB, the orchestra recorded instrumentals alone and scored a chart-busting hit in “TSOP—The Sound of Philadelphia.”

Renaldo remembered the excitement because he missed it so. “It’s a shame the way they let this thing rot,” he said. “Kenny was a genius, he was phenomenal at bringing out songs and matching songs with artists. He would just go to the singer and say, ‘This song is for you; it’s a hit.’ Huff didn’t talk much, but he could communicate through his piano.

“The first problem was that Kenny was too loyal, he was loyal to guys who didn’t deserve his loyalty, guys he picked up off the street and gave jobs to because he thought they had something. Guys who would curse him behind his back. I just think all these guys got greedy. The original rhythm section broke up because those musicians thought they were worth more.

“Then toward ’75 to ’76 all sorts of stuff started going down. Guys like (staff songwriter) Gene McFadden would walk around bitching, even when the press was there. ‘I want my money from that fuckin’ nigger,’ he would say. Kenny was under a lot of pressure. The payola investigation was going on. But the worst thing for Kenny was his wife. He was freaked out over Dee Dee, and she wasn’t happy. Kenny was very sick for a while. He’s much better now, but I guess at the time he really had a nervous breakdown.”

Renaldo had also started to see a lot of religion being peddled. Gamble had always been religious, wrestling with different faiths for years. His deep beliefs showed up in preachy song lyrics and rambling pseudo-philosophical album cover notes. Then Bobby Martin got the calling. Martin wasn’t well-known to the public, but his arrangements were almost as important to The Sound as the songs themselves. Martin had been having trouble with his wife, and one day, so the story went, some Jehovah’s Witnesses stopped by his home. The next day, between recording sessions, Martin started analyzing passages from the Bible for the musicians. The musicians, a healthy mix of white Italians and gospel-trained blacks, sat politely while the possessed arranger laid his religious trip on them. Then one day he was gone.

While Renaldo was sad that The Philly Sound had been all but silenced, his concerns were at least partially financial. He felt the group MFSB was still viable. The group had never grown huge simply because Gamble had never wanted to promote it. He was encouraging producer Thom Bell to buy the copyrighted name MFSB from Gamble so the group could record again.

Renaldo had given me something new to think about. If his story was correct, a palace revolt of sorts had taken place. But, more importantly, The Sound may have been brought down, not by the forces of the record business, but by the forces tugging at one man—Kenny Gamble. Gamble had been involved in a painful divorce, and some employees claimed that he sometimes would stroll through the halls of the Philly International building in a daze, not hearing anything that was said to him. He had been accused of losing touch with the business and failing to innovate as he once had, but perhaps the truth was that he had been too distracted to see where the industry was going. It was time to speak with Gamble.

I called the Philadelphia International offices. Lawyer Asbury still couldn’t come to the phone, as had been the case for the past two weeks. Gamble wasn’t in, hadn’t been in the day before, wasn’t due in. Nor was Huff. They all had to know that I wanted to talk to them—the word had gotten out that I was looking into the company. It was clear that they weren’t going to help.

In the interim I was reading a book on the music business. I wanted to know what kinds of pressures were on Gamble, whya man who in 1977 had apparently fulfilled his lifelong dream of owning a lucrative record company would, only a few years later, seemingly succumb to the pressures of a business he was obviously very good at. One thing that helped was the book, by Clive Davis. Davis had been the president of Columbia Records when that company had put up the money to start Philadelphia International Records. Davis, probably the most highly respected and controversial figure in the business, had noticed the work Gamble and Huff had been doing with two tiny independent labels they had started in the late ’60s: Gamble Records and Neptune Records. More importantly, he had seen what the dynamic producers had done with several talented performers whose careers were on the skids. They had remade soul singer Jerry Butler, giving him a new sound, three smash singles and two hot albums. The way Gamble described the process at the time, it sounded as though he and Huff could do these musical make overs at will. “Jerry was a great singer. But he was cold, man,” Gamble told an interviewer. “We sat down with Jerry, and we wrote some songs together. Then Bobby Martin did the charts, we took our regular guys into Sigma Sound, and we gave the guy hits, real hits, man.” They had done the same thing with Dusty Springfield (“Brand New Me”), Wilson Pickett (“Don’t Let the Green Grass Fool You”) and Joe Simon (“Drowning in the Sea of Love”). This wasn’t just prefab formula music, though. Each artist had been given a sound tailored to his or her own talents. Gamble and Huff had become a musical consulting firm—hit doctors.

The Davis book made me aware of the heavy pressures on hit makers like Gamble and Huff to follow smash tunes with more smash tunes. Most record contract deals run for five years. But they are really five renewable one-year contracts. By 1976, a number of artists were pushing hard for more money—especially since Gamble and Huff had obviously been raking it in.

The two biggest malcontents at Philadelphia International, according to a number of people, had been McFadden and Whitehead, the songwriting team. Gene McFadden and John Whitehead had gotten a lucky break in 1966 when their group was asked to tour with soul legend Otis Redding. Two years later, Otis was dead, the victim of a plane crash, and McFadden and Whitehead were struggling. Then they came up with a song idea—it became the giant hit “Backstabbers,” and McFadden and Whitehead signed with Philadelphia International as songwriters. They went on to write some of the company’s biggest hits. Associated with Gamble and Huff for ten years, McFadden and Whitehead long complained that they were being ripped off. Don Renaldo felt that they were just greedy. But I needed to hear their side.

McFadden and Whitehead had left Gamble and Huff last year, and now they had released a new record on Capitol. I arranged to meet them at McFadden’s home in Somerdale, New Jersey.

“This Could Have Been a New Nashville”

McFadden turned out to be a calm, soft-spoken family man. As we talked he stretched out on the ultramodern modular furniture that filled his spacious home. He was tired. Most musicans are tired in the daytime. They don’t really come alive until about 9 p.m., when they normally start work. They are night people, and the daytime seems to hurt their eyes. Whitehead seemed manic, hyperactive, flying into the living room wearing a black jacket with his karate club insignia and only touching the ground occasionally to make a point. Together the two made a funny pair—McFadden calm and cool; Whitehead frantic.

Both musicians talked easily about the beginning of their relationship with Gamble and Huff. “If they had told us to go sit in the middle of Broad Street and write songs, we would have done it,” Whitehead said. “It was a great thing. We came into the office every day and sat there and worked on tunes. What a great job.”

They had been instrumental in Gamble and Huff’s hit-factory approach. Instead of letting staff songwriters do whatever they wanted, Philly International gave the writers specific projects, sometimes even a theme for the day. “Gamble would come in to us and say, ‘Write me something about soul city walking’,” Whitehead remembered. Sometimes, Huff would go to all the writers with the same title to see what they would come up with. Huff would walk into each writer’s office and say, “Love is …,” leaving an open end. At the end of the day one guy would have “Love is you,” another would come up with “Love is astinking mess” and still another would write “Love is everything.”

But soon dissatisfaction over money had set in. “Look,” said McFadden, “we signed the contracts so it’s hard to have many regrets. I chalk most of it up to experience. But we had no publishing rights at all at Philly International—they made it a business point that the company got all the publishing rights. That means they take 50% of the royalties off the top before the writers get to split anything. We started to meet more people in the business who did the same thing we did, and they were making astronomical money. We didn’t know a good deal from a bad one at the time, but some of these guys were already livin’ on the Main Line! We didn’t think we were gettin’ our fair share. After all, we were writing the songs. Without the songs there’s nothing!”

Their gripes had been directed against Gamble. Huff, it seemed, was the silent partner through all this. Everyone I talked with had spoken at length about Gamble, but nobody had much to say about Huff, except that he was a brilliant musician and that he kept the company going musically while Gamble worried about business, politics, the Black Music Association he was pioneering, Islam and a variety of other interests. People said that Huff, the quiet piano player, hadn’t received the recognition he deserved. McFadden and Whitehead confirmed the rumor I had been hearing on the street for weeks: that Gamble and Huff had had a serious falling out. Once close friends, the two were now barely on speaking terms.

Like others in the company, McFadden and Whitehead had seen that the big money in the music business was in vertical integration: being able to do several jobs besides songwriting. They had wanted to perform again and try producing. Gamble urged them not to, claiming that if they continued as songwriters, they would have longer careers and make more money. He finally relented just to shut them up.

The first song they had done as artists and producers, in 1979, had been a monster hit. “Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us Now” was a gold record. The way it was received and interpreted in the black community was indicative of the political forces at work within the company. Everything that came out on the label was now being seen through a black lens. And because of that, the songs were becoming less popular with white record buyers. People were calling “Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us Now” the new black national anthem. Gamble’s overall thrust had been black unity through music—his formal declarations had been clearly written out on the album jackets of every record he produced. “Understand while you dance,” Gamble had written on the back of a 1976 O’Jays record called “Message in the Music.” “The word with music is one of the strongest, if not the strongest, means of communication on the planet Earth. It is the only natural science known to man. The word with music can do its part to calm the savage beast that lives in every man. The message is Unity.”

But Gamble was trying to preach two different messages at the same time. One was that blacks should band together, realize their own worth and make themselves a force in the community. The other was that whites and blacks should live together in peace. There was, of course, somewhat of a paradox here: unification through separatism. The problems inherent in his thinking weren’t much different than those inherent in the whole crossover concept. A black song had to be a smash on the black charts before crossing over to the white charts. But beneath that was the question of why there had to be two charts in the first place.

To McFadden and Whitehead, “Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us Now” meant something completely different. It was a personal statement, not a political one. “We wrote the song because, after being kept away from singing for so long, Gamble finally said we could make our own record,” Whitehead recalled. “If anything, the song was a declaration of our independence from Gamble. The ‘things that were keepin’ us down’ in the song were Gamble’s ideas about how we could best serve his company. We didn’t mean the song to say, ‘Get off your butts, black people.’ We tried to put a message in our music, but it was a universal message. We write about what happens in our own lives. These aren’t ideas that are just for black people.”

But these battles had been ideological. There had, in fact, been earlier strains on the business. “Kenny had a nervous breakdown, and a lot of things changed after that,” McFadden said. “His personal life did that to him. Maybe the business was a little thing that turned the screw some more, but the screw had already been turned. Dee Dee wanted to be a singer, and I think he just wanted her to be his wife. She was probably thinkin’ her husband owned this company that was makin’ all these singers big, why couldn’the make her big?

“But the real reason The Philly Sound didn’t last was because longevity wasn’t on their minds. They weren’t a record company per se, they were Gamble and Huff. The public don’t even know the names of most record-company execs. But Gamble and Huff didn’t want anyone to be bigger than they were. If you want ego in this business, you should be a singer. Then everyone knows your name. If you want to be an executive you can’t want fame—it don’t match. You’re competing against your own people. We could have had a new CBS Records right here in Philly. This could have been a new Nashville.”

A new Nashville, a cash-rich, highly creative record capital here in Philadelphia. How had Philadelphia missed out on such a golden opportunity? The Sound of Philadelphia had been the most recognizable symbol of the city since the Liberty Bell. Though Philadelphians did not always realize it, across the globe radio listeners and record buyers couldn’t get enough of TSOP—the sound that had Philadelphia’s name as part of its trademark. Philadelphian ever really found out about The Philly Sound because the local establishment had never gone out of its way to support Gamble and Huff’s efforts, no matter how much money their company had pumped into the local economy. “The Sound of Philadelphia is everything Mayor Rizzo don’t want to hear,” someone had told British author Tony Cummings while he was researching his book on the music. “That’s why there ain’t no statues of Kenny Gamble or Leon Huff up in front of City Hall. The white folks … might have a sneaking admiration for the money the singers or the record companies make, but they sure ain’t gonna let the city elders bestow no recognition on them to honor their music.”

It seemed to me that losing The Philly Sound was more than just another large local company closing up shop. For Gamble and Huff personally, considering the millions they had made, bankruptcy was hardly a possibility. But it was the end of a powerful team with the gift for bringing people together. Kenny Gamble had been on to something. “The message is Unity,” he had written. But the message was in the music, and the music needed to continue if the message was to get across. The irony was that when Gamble took his attention from the business to refine his message, he slowly lost control of the medium through which the message was delivered.

I wanted more than ever to talk with Kenny Gamble to see if he had the same understanding of what had happened to him and his company—to his life.

Finally, the Philly International lawyer called. He said Gamble didn’t want to talk to me now, that he didn’t want to say anything publicly until his next move in the record business had been settled. Big things were in the works. Teddy Pendergrass’s manager also called, explaining that Teddy, too, didn’t want to go public unless he had good news, like a new record or a medical breakthrough in his partial paralyis. Thom Bell, the producer who had done so much work with Gamble and Huff, was living in Seattle. He never answered at the phone number his lawyer had given me. But by this time I had spoken with dozens of sources—other MFSB members, journalists who had interviewed Gamble and Huff, entertainment lawyers, studio technicians—and had read every article ever written about Philly International. Even without the principals’ cooperation, the pieces were falling into place. There was only one man left whom I wanted to speak with and who wanted to speak with me. He was Roland Chambers, guitarist, arranger and conductor extraordinaire, and one of the few people who had remained friendly with Gamble from childhood through the present. We met at the home of his manager, singer-turned-producer Rena Senakin.

Roland and Gamble had met in their early teens: they started out singing doo-wop music in subway stations because the echoing sound they got there was so impressive. Roland had hung around with Gamble and Thom Bell in the early days when the two were trying to peddle their services to Cameo-Parkway. He had been their guitar man, becoming a well-known studio musician by age 18. He had also known Leon Huff and had watched the funky pianist rise through the studio system and then join Gamble as writer and producer. And when the word had gone out in 1971 that a record label was to be started by his old Philly pals, Roland had quit his lucrative job conducting orchestras and playing guitar for Marvin Gaye, the Motown hit maker. He had become part of The Philly Sound, a member of the upper echelon at Philly International.

For the first few years, it was a heady experience. But as The Philly Sound began to be widely copied, Roland knew that the magic was dissipating. The sound was becoming repetitious, like the disco craze it had spawned. “After a while,” Roland remembered, “we would be playing a tune and I’d be thinkin’, ‘Hey, didn’t we cut this yesterday?’ ” As the old acts left and the solo vocalists dominated the label, The Sound of Philadelphia became less experimental, more standard. There were fewer “crossover” hits—the audience became blacker. Many of the innovators had left, and Gamble hadn’t been able to replace their spontaneity.

By this time, Gamble had been telling Roland that making records just wasn’t fun anymore. Gamble had the headaches that the president of any large corporation had. He could no longer lead the loose musician’s life. He began telling friends that the music no longer motivated him. And it showed in the music.

“What Gamble and Huff had together wasn’t man-made, it was a gift from God. You can debate all you want about why it isn’t happening anymore, but the most amazing thing is that The Philly Sound actually existed.”

The stress of the payola scandal, his problems with his wife and the responsibility of employing a large work force had proved too much for him in 1976. He had had what was described by friends as a breakdown. Out of commission for nearly four months, he never really bounced back. It wasn’t that Gamble had lost his marbles, as many Philly International employees believed. Gamble had just found his marbles. When his relationship with Dee Dee Sharp had failed, he had realized that he was approaching 40 and hadn’t much of a family. He had become a very rich man. He no longer needed the record business, and it was no longer exciting to him. He turned to causes, black causes. Some people interpreted his involvement as political ambition. But really, Chambers said, what Gamble was doing was searching for himself, something he had never found the time to do while racing to the summit of the record business.

“You know what Kenny’s been really into the past couple years?” Chambers asked. “His kids. He’s learning how important all that can be.” Gamble hadn’t remarried—his divorce had only recently been made official—but, according to Masco Young’s column in the Daily News, he had moved in with WDAS DJ Deanna Williams, and the couple had two children.

While Gamble was finding himself and building a relationship with his family, he was losing the older relationship with Huff. Huff had grown indignant, feeling that he was doing most of the musical work—and sharing all the credit.

It was time to regroup and change direction. After delaying, Gamble finally bit the bullet. Last summer, he laid off everyone but his lawyer, the administrator of the publishing company and a few secretaries. “I think it was more of a relief than anything when Kenny finally had to fire everyone,” Chambers said.

As our conversation ended, Chambers’s manager, Rena, came back into the room. She had been busy taking care of her new baby and had overheard much of our discussion. As Chambers and I had dissected the demise of The Philly Sound, we had missed the most important point, Rena felt. “No matter why The Philly Sound ended or how long it was fresh and exciting, the point is that it happened,” she said enthusiastically. “The fact that all those great songs got made—that’s a miracle. What Gamble and Huff had together wasn’t man-made, it was a gift from God. You can debate all you want about why it isn’t happening anymore, but the most amazing thing is that The Philly Sound actually existed, that the music is there, that the music will always be there.”

I came back to my office and popped on the tape machine. All the inspired Sound of Philadelphia was still there. Frozen in time, the time that was my youth, I found myself thinking. I was still hung up on that phrase, the phrase from the crash scene, the phrase from Masco Young, the phrase that so well described the annoying circularity of life—life that was always more easily seen while digging through the past than while confronting the present. “What goes around, comes around.”

For a short time, Gamble and Huff had been able to hop off the merry-go-round of racial divisions and cut across the lines of skin color. They had crossed over, reaching blacks and whites at the same time with the same music and the same message. The saddest thing about their fall was that it signified the end of that common ground between the races. Then again, the fact that they had done it at all, that even for a short period of time there existed such a common ground for the races, was something to be thankful for.

“What goes around, comes around.” The more I thought about it, the more I realized the phrase applied to me. It was a lesson I had to understand, that real people don’t continue doing the same things, making the same sounds over and over again if they don’t have to. They grow and move. And if they leave a fan like me who loved what they had done in the lurch, then it was my loss—not necessarily theirs.

They say art grows out of frustration, fear, disillusionment. Artists create from that fertile stew of emotion. But the reason we live is to get past the times when we are miserable. Ever since The Philly Sound had lost its verve for me in the late ’70s, I had been asking why. What I was really asking, though, was why men like Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff hadn’t wanted to stay in one place for the rest of their lives so I could have more of the music that I so identified with my past, with growing up.

I was sorry that I had never had a chance to meet Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff. Not that I wouldn’t have wanted to ask them to wax nostalgic about how great the glory days of The Philly Sound had been. But more important, as a fan I wanted to tell them that they didn’t owe me anything, that they had already given me a lot. I wanted to let them off the hook.

Being a fan isn’t that much different than being an artist, I thought. What goes around comes around. Artists have to move on to keep fresh and alive. So do fans. It was time to move on.