The day Pascual Perez has finally reached the New York Yankees spring training camp, a clubhouse man entrusted with Perez’s jewelry bag is unable to resist the temptation to put it on the scale on which the New York Yankees weight themselves each morning. It registers 5½ pounds. Since Perez himself appears to weight about 65 pounds total—naked, he looks like one of those old-style wooden hatracks you would have found in a private eye’s office in 1936—the idea of five pounds of paraphernalia draped upon his spindly shoulders seems remarkable.

“Five and half pounds,” says the clubhouse man. Standing only a few feet away, Dock Ellis registers only mild surprise. Dock Ellis is entranced by another excessive tableau: his own upper torso. He has stripped off a Ralph Lauren polo shirt to reveal his upper body, and is now flexing in front of a mirror, striking the kind of poses you find on the covers of magazines that sit next to the heavy metal fanzines in the 24-hour convenience stores. As he flexes, the scripted tattoo that reads “Manhattan Dock” on the top of his left bicep rides like flotsam on a gently rolling sea.

With the scowl and the grunts, and the earring, and the shaved head, and the ripples of cartilage and muscle and whatever else it is that’s stuffed beneath his skin trying to get out, Dock Ellis looks like a cross between Charles Barkley and Mr. Clean on a bad day.

Dock Ellis’s first words, uttered at this point, contain an obscenity this paper’s style book does not allow. Roughly, his words are, “I’m a bad mother.” He draws out the “bad” into six or seven syllables and will use “mother” in one form or another in nearly every sentence. And if the profanity and the posing are largely an act, it’s still hard to ignore that once, as a pitcher for the Pittsburgh Pirates, he tried to hit every batter in the Cincinnati Reds’ lineup, and, years earlier, had climbed into the stands with a bat in pursuit of a man who’d been hurling racial slurs. Anger seeps out of Dock Ellis’ pores so thick it fills the air like ozone after an electrical storm. It seems to be a good anger, a healthy kind of hate, but that doesn’t make it any less stunning.

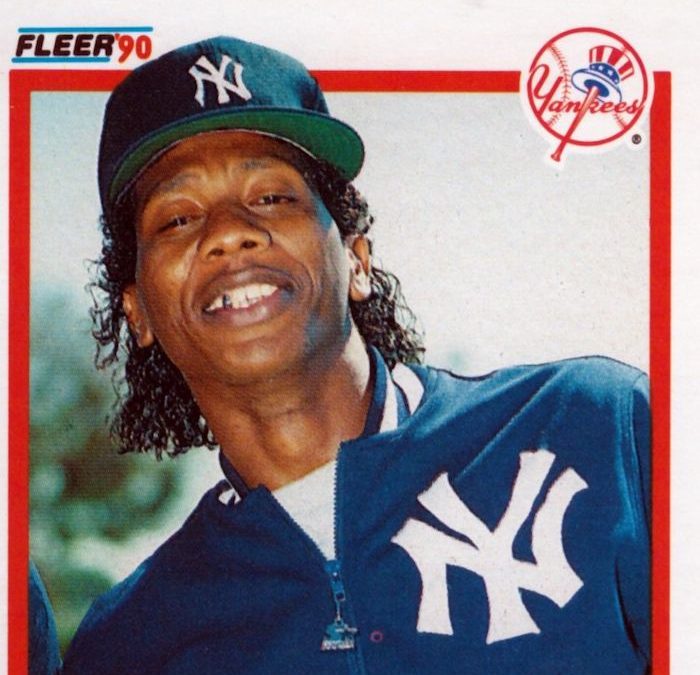

Finally, Ellis pulls his shirt back on and starts to browse the lockers in the empty locker room. The Yankees are in Port St. Lucie, and Ellis is bored, waiting for Perez to finish his running out on the field and shower, after which Perez will don a stone-washed denim designer suit with two blue leather belts arranged one on top of the other, and sunglasses with the bright white frames and the dark, dark lenses. The curls of his hair will cascade like a waterfall to just touch his coathanger shoulders. The necklaces will pile so deeply on the front of his chest that the layers of gold will give him the appearance of actually having a chest. The bracelet on his left wrist that spells “PEREZ” in diamonds will anchor the ensemble.

And the two of them will stride out into the parking lot, to Perez’s black Jaguar, the counselor to the counselee.

And now George Steinbrenner has hired a man who once threw a no-hitter on LSD. Only in the pinstripe universe.

In the meantime, all the faceless names on the lockers have put Dock Ellis in a mind to reminisce about his winter as a pitching coach for the St. Petersburg Pelicans, the champions of the Senior Professional Baseball League.

“They were dumb when they played in the majors, and they’re still dumb now. They were asses then and they’re asses now. They were crybabies then, they’re crybabies now. They were con artists then, they’re con artists now.”

The words stomp on the stillness in the virginal spring dressing room; they are too heady and blunt for this early in the year, when the whole fabric of the game is still without flaw. He is down at the far end now, where his own locker once was, down in the dark reaches reserved for the numbers in the 60 and 70s.

“Guys thinking they can still do it because they did it up there? Just con artists,” comes the voice. The man is out of sight amid all those virgin uniforms, the syllables raining back in rhythmic syncopation: “Conning themselves. Talking about the businesses they own back home. Own, my ass. Mashin’ nails is what they’re doin’. I wasn’t even talking to half of them by the time the season ended.”

The pate is visible again, stalking back down the carpet, under full steam.

“Try to con me? I’m a bad mother. But at least I know what I am.”

This is all well and good, it is suggested, this ability to move through the world by chewing it up and spitting it out. But what is unclear is its relevance to the here and now, wherein the baddest mother in the state of Florida is being asked to counsel the New York Yankees’ prize bejeweled jewel, who happens to be a man with the psychic stability of a hummingbird. It is suggested that we are now treading on more fragile ground. This is the inside of someone’s head we’re talking about. Not just anyone’s head, either. Pascual Perez’s head.

“His head? I’m not going into his head,” Dock Ellis says. “I’m his counselor. That’s all. It’s up to him to throw the motherf—in’ pitches. I’m not gonna throw the pitches for him.”

Dock Ellis. Ninja therapist. “And I’m a bad mother counselor,” Dock Ellis says. “I’m DAMNED good.”

There didn’t seem much wisdom in doubting him.

At first glance, they are baseball’s oddest couple, on is a Chthonic, oaken-hewn man of 44 who was spirited and earringed and delightful when he played. He once was nearly great, but the pharmacopic quicksand in which he lived his life closed over his head. His legacy now is a series of admissions of drug-soaked no-hitters and on-field amphetamine lunacy that haunt the halls of baseball record books like the ghost of Marley rattling his chains out in the stairwell.

The other is a skittish, foppish, grass-blade of a man, 32 years old, who could be great if he stays out from under the drugs. His on-field mannerisms furnish the game’s most delightfully anarchic ballet of eccentricity since Mark Fidrych. But living as he does on a razor’s edge of rationality, he is prone to falling off frequently, and often to the wrong side, so that he is given to throwing the beanball, and bouncing baseballs into opposing dugouts, and, until a year ago, dabbling in all the wrong substances.

This is where Dock Ellis comes in. To hover in the corner of Pascual’s eye, wearing what he, Ellis, likes to call The Look. To offer a little advice. To teach, by example. And to stomp on Pascual’s head, metaphorically anyway, should Perez get any silly notion about lapsing again.

On closer reflection, then, perhaps it isn’t all that odd. Both talented, both addictive in personality, both living in that netherworld inhabited by certain athletes who are more comfortable on the fringe.

But now add to the equation their employer, and the oddity of the situation in the New York Yankees camp grows exponentially. The Shipbuilder is a man who has made a habit of surrounding himself with former DEA and FBI folks, apparently to save himself from himself, because his own lifetime’s moral web just grows tanglier by the minute. He is also a man who has fortified his strong-training camp with so many fences and cops and security guards that it’d be easier to raid Entebbe than gain unauthorized entrance. Clearly he has an affection for law and order.

And now George Steinbrenner has hired a man who once threw a no-hitter on LSD. Only in the pinstripe universe.

“I like Dock,” Steinbrenner said the other day, in the parking lot of the Yankee compound. “I like what he’s done with his life. I used him to talk to our minor leaguers the last two years, and I liked everything he did then. I like what he’s done with his life.”

The details of Ellis’s addictions are woolly indeed, and exclude no substance know to the imagination. Since leaving the game and completing a 45-day rehabilitation at The Meadows in 1980, Ellis has taken psychology classes at Cal-Irvine and worked with prisoners and wayward youths. He describes himself as a freelance drug and alcohol counselor with several clients, a therapist-of-all-trades without portfolio. “When one of my teachers asked me to start teaching his interns—people who were getting their degrees—that’s when I realized I was a professional counselor,” he says.

After consultation with Tom Reich, agent for both Ellis and Perez and an old ally of Steinbrenner’s, the Yankees have hired him to counsel Perez, a sort of psychic insurance policy for the $5.7-million man. But no one’s given him a title. He is not a coach, not on the staff in any way.

“How about mental bodyguard?” suggests a Yankees publicist.

Titles seem too tame for a man who is seldom unwilling to share an insight, except that he’s so loud, they’re better described as outsights.

Here’s Dock Ellis the political scientist, for instance, on how we can solve the drug problem:

“Blow the mothers out of the sky. I don’t care if it’s the president of Mexico on the plane. If they don’t respond on the radio, blow them out of the sky. Attach a bomb to every single drug coming into the country. It’s the only way. Bush gives us $395 million to fight the war on drugs? The Crips and the Bloods make more than that in a year.”

Here’s Dock Ellis on the life philosophy of Dock Ellis:

“No one’s ever going to control me. If I get to the point where I don’t like something, I leave.”

Here’s Dock Ellis on what Dock Ellis of the Pelicans would say to the pitchers when he’d visit them on the mound:

“You’re 35 years old! What are you doing? Throw strikes! My manager tells me to use diplomacy? This is diplomacy.” And he brandishes a fist the size of a pineapple, all bristly knuckles.

And here’s Dock Ellis on Dock Ellis the player:

“I was a flake. Sparky Lyle was a flake. Cedeno was a flake. Andujar was a flake. It didn’t hurt them, did it? I’m still the old Dock. I’m just not loaded all the time anymore. I’m still a flake. Perez is a flake. He still comes to play.”

In Perez’s case it’s literally true: he comes to play baseball and to play.

“Well, you never know about yourself. You can go to sleep thinking you’re going to have a good dream,” he says, “and you end up having a nightmare.”

“People talk like I’m crazy, the way I act,” Pascual Perez says. “Uh-uh. That’s my normal thing. I can’t change the way I am. I am what I am. A lot of people been talking about how it’s a bad investment for the owner. It’s not. I’m a winner.”

Lifetime, just barely: 64-62. Perez’s career plots a map of careens. After a 15-8 rookie year with the Braves, he was arrested in the Dominican Republic with a small amount of cocaine in his wallet in January of 1984. He served three months in prison.

“People were jealous of me,” he says. “Now I trust no one except myself, sometimes.”

Sometimes?

“Well, you never know about yourself. You can go to sleep thinking you’re going to have a good dream,” he says, “and you end up having a nightmare.”

He returned in 1984 to win 14, the most victories on the team. In ’85, though, he slumped to 1-13, and in the spring of 1986, amid various rumors, the Braves put him into Fair Oaks Hospital in Del Ray, Fla. for a 30-day stay that lasted 15.

“I didn’t even know what rehab is,” he says, with a wave of his hand.

Soon after Perez left the clinic, the Braves released him. He returned to his home, and vanished from major league baseball’s conscience, until the Expos ventured down and signed him to a minor-league contract. Low risk. High payoff. In ’87 and ’88, he won 19 of 27 decisions. Then, in the spring of ’89, after hearing disturbing rumblings about his behavior back home, the Expos flew to the Dominican Republic, snatched him from himself, and put him in the Palm Beach Institute, Florida’s oldest private substance-abuse facility.

“I relapse,” he says. “I lose everything. I lose my confidence. I lose me. I stay 60 days. This time, I was alone a lot. I worked at it. I realize you can’t fool yourself. But I never been into it much, I was never addicted, and I thank baseball I was saved.”

So far, that cure seems to have taken. He went north with the team last spring, and after a rough start, was gaining momentum at the season’s end. Perez’s primary therapist at the Palm Beach Institute will take credit for only one thing: “I worked on his hitting,” Fay Hewitt said from Palm Beach.

Hewitt has been straight for 16 years. He has a master’s in social work. He is the institute’s clinical director. He gives all the credit for Pascual’s success in the outside world to the Expos, whose roster features five recovering abusers.

“They had team members watching out for him,” Hewitt said, “getting him to meetings, helping him out. They thought having people around as part of the aftercare would be a good thing for Pascual, and we agreed with them. We thought that was real progressive thinking on their part. They’ve passed on to the Yankees that he may need some more care and monitoring during the season than would normally be expected.”

“I don’t think there’s any question any person with the type of difficulties that he has had needs care and understanding on a daily basis,” said Dave Dombrowski, the Montreal general manager. “All it takes is one day for an individual to slip. He is extremely different—fragile, extremely emotional—and you have to make sure that everyone around him is aware of that.”

The Expos’ success with Perez last year relied heavily on peer support—specifically, regular, confidential meetings between several players—some with troubled pasts, some not—led by a member of their employee assistance program, Eddie Heath, who frequently travelled with the team.

The Yankees have said they will require Perez to check in with the Smithers clinic regularly, and will call on Ellis, who currently lives in Los Angeles, to visit New York during the season. In addition, they’ve hired Joe Sparks, the former Expos hitting instructor, as a third-base coach. Sparks, Steinbrenner says, will also be there to help Perez. Yankee General Manager Pete Peterson says support on the road has not been discussed.

“Signing him to a contract is just the beginning,” Dombrowski said. “The day you think a person has overcome those problems is the day you are helping him toward a setback.”

“We’ll give him all he needs,” Steinbrenner said. “I’m not saying he needs help. But we’re going to give him any assistance he might need. Dock will be into New York frequently.”

“Dock’s gone through it,” Peterson said. “If you go through it, you understand better. Dock’s different. Sometimes we don’t understand how other people are brought up. You can misunderstand the kind of person they are. Now, Dock did some things. He might understand some things where we don’t.”

In Ellis’ world of black and white, right and wrong, you’re in or you’re out. You come to play ball or you don’t come to play ball.

Peterson is the latest Yankee general manager to pass through the cursed portals, but he brings a beguiling open-mindedness about all things baseball. On matters Perez and Ellis, he knows whereof he speaks, having managed Ellis in the minors and authorized the signing of Perez by scout Howie Haak in 1976.

“They’re good people,” he said. “They’re the kind of people I like to be around. Pascual is a character. And I like that.”

Hewitt, who has offered his services to the Yankees, offers a final caution that the support group should be diligent, and not easily fooled. The rehabilitation of Pascual Perez carries an added dimension. He can charm the gold plate right off a necklace.

“You’ve got to be aware of that,” Hewitt says, “and not let the charm overtake good common sense. That black Jaguar almost cost me my job last year. He had about three days to go before he completed the program. I let him get it. I should have known better, but he’s got the big eyes and the smile, and I got a hug, and I thought, “It’ll be all right!—until he went for a ride which he wasn’t supposed to. If he’d been seen driving or hit something, I’d be out of work.”

The next morning Perez has just come in from throwing, and he feels good. Great. Explosive. The ball had the proverbial pop, he’d gotten over the weariness of leaving the island under the cloud of a paternity suit, and he was pitching. He’d paused for a few seconds on the field to pose for the covey of photographers, all grinning with that silver tooth—“My voodoo tooth”—and then, before half of them could even find the right lenses, he was gone, a shimmer, was he even there?

Now he is standing in the middle of the locker room. He can’t find the right words to describe how good he felt throwing the ball. Instead, he smiles and starts firing his arm away from his chest in a martial-arty motion.

“Boom!” he says, each time. “Boom!” And he grins the grin with the silver tooth. You want to hug the guy. You know what Fay Hewitt was talking about. Pascual Perez, caught alone, away, can be a remarkable man, prone to stunningly poetic turns of phrase, the words lacing themselves like vines on a lattice, never quite getting to the point, but entrancing just the same.

“Sometimes you lie down and meditate and turn off the light and you think about what kind of life you are living,” Pascual Perez is saying. “You think about growing old and dying. And then you open your eyes and you’re in the same place you were when you closed them. The world is like that. You pass around it three times, and you’re back where you started.”

“I’m going to tell Perez that in New York he can be as close to being a god as he’s ever going to be, if he wants to be a god.”

Really?

“That’s what Dock said,” Pascual says. “This is my third try around.”

What about taking life one day at a time? The normal addict’s mantra?

“We haven’t gotten to the ‘Take it one day at a time’ part,” he says. “Dock is a great guy. I like what he said. I agree with what he says. He has a reason to talk like that. He’s been on the street. He knows. He’s been there.

“And,” says Perez, the sartorial king, “he even looks better than he did 15 years ago.”

It’s true, he does, although this might have something to do with the fact that 15 years ago Dock Ellis was arriving at the park in hair curlers, and was invariably high—on speed when he was pitching, on cocaine or marijuana on days he wasn’t—and one of the things about controlled substances is you don’t always look your best under their influence.

He’s been straight 10 years now. In his talk of pressure, and susceptibility, and all of the rest, Dock Ellis doesn’t sound much different from any other recovering addict or any other substance-abuse counselor. What you get with Dock Ellis that’s different, of course, is the package. A few hours in conversation with Dock Ellis is like taking a stroll with a Doberman on crystal methadrine.

But on this morning, sitting in the empty stands of Fort Lauderdale Stadium, Dock is uncharacteristically reflective. It’s as if the sun, which is bringing beads of sweat to his bald head, is dulling the edge of his mania.

“Pascual’ll be all right,” he says. “He comes to play ball.”

This is the thing, then, the qualification, and it’s not as facile as it sounds: He comes to play ball. In Ellis’ world of black and white, right and wrong, you’re in or you’re out. You come to play ball or you don’t come to play ball.

“Just keep him focused, that’s all,” Ellis says. “I don’t think there’ll be a problem. People anticipate a lot of problems. I’m sure he’ll be fine. I won’t say … I mean, nothing’s a guarantee … but he’s a good dude.”

On this morning, a field full of pinstripes has excised all the talk of Pelicans and Dock Ellis’s ire has begun to melt into a pool of nostalgia. What was. What could have been.

“I’m going to tell Perez that in New York he can be as close to being a god as he’s ever going to be, if he wants to be a god.

“If I’d had someone like me to counsel me, I’d more than likely still be playing baseball,” Dock Ellis continues. “Who knows, though?” Maybe I wouldn’t have listened. But I do know that you put on pinstripes, you’re in a new world. It just didn’t dawn on me until after. It wasn’t on my mind, because I was on drugs every day.”

In fact, the more you think about it, the more it all makes sense. There was no one more New York Yankee in 1976 than Dock Ellis, at least to a very specific generation of Yankee fan—the generation whose adolescence coincided with the gutter years, the decade of ’65 to ’75, when Jake Gibbs and Fred Stanley and Horace Clark and Bill Burbach and Steve Kline and Rusty Torrez and Mike Hegan and Bill Sudakis and Roger Repos and Jerry Keuney prowled the empty Stadium. The carnage was so thorough that the city had to revamp the stadium simply to exorcise the blight.

So when Dock Ellis helped them to their first pennant in 13 year in 1976, to a few thousand diehard kids anyway, he became far more an immortal than the likes of DiMaggio and Maris. And so now Dock wants to help George (“I like George—he wants to win”) and help Perez and help the Yankees win after another decade of drought. There’s some symmetry there.

They have this in common, too: the maniacal lust to win, the power that perverts so effortlessly. In Ellis’ case, it was manifested by throwing beanballs, over and over, blind and possessed; tired of the Reds intimidating the Pirates, he wanted to intimidate back, all because he simply wanted to win. With Steinbrenner, it manifested itself right after that pennant and the 4-0 whitewashing by Bench and the Reds. It didn’t have as much to do with his personality and his bluster and weird ethical structure as it had to do with how he started to buy up his enemies. In ’76 Don Gullett beat him, so he bought Don Gullett . The next few years, Tommy John and Luis Tiant beat him. So he bought both of them. That was blasphemy. It was cheating. And, of course, he traded Dock Ellis.

Now, though, there’s promise for a small vindication for all, in the kind of Byzantine plot that only the Yankees could contrive. The owner, beyond redemption (in the eyes of Yankee fans, anyway) has turned to the counselor who has redeemed himself, and asked him to save the pitcher who could falter—leaving for the few remaining faithful, one last ray of hope, rising out of the bluster and rubble of all that George has wrought. All of which makes the trinity far less unholy that it appeared at first sight—at least, under the fragile light of spring.

[Photo Credit: Fleer]