By the banks of the Truckee River, under a nearly full moon, a tall, vaguely Hispanic-looking man with beautiful shoulder-length black hair, a foot-long beard, and a plump, perfectly relaxed body comes over to tell me that Satan is walking proud. He introduces himself as Jacob, slips a small U.S. Army pack off his shoulder and tells me he just missed the midnight bus out of town.

“Satan’s walking proud through the cities,” he quickly amends himself, taking a deep whiff of grass and river. “That’s why I’ll only work migrant, out in the country. I know the joy of the mountain cat’s full belly,” he says, fixing me with an aggressively devout smile, “and I know the pain of the deer that’s in there.”

It’s my third night in Reno, and I’ve come down to this river that snakes through the center of town for some fresh air before turning in. I was hoping to spare myself that 24-hour passion play of the casinos, but there’s no escaping it here: Heaven and Hell are married on every other street corner in Reno. Two blocks down, across from the Washoe County District Courthouse, where I’ve been spending my days watching the Judas Priest “subliminals” trial, a storefront window advertises summer cut rates for their QUICKEST MARRIAGES IN RENO. Three blocks up, the Truckee used to glisten as it crossed under the Virginia Street Bridge—from all the wedding bands thrown in after the quickie divorces. And Jacob, though his voice is warm and clear as a bell, has blue-green eyes that flash from one extreme conviction to another with a scary rapidity. I’ve gotten used to people like him by now, picking me out of a neonlit crowd on Sierra Street to announce Apocalypse to, spilling out of the casinos at two a.m. on a 90-degree Saturday night and offering to mow my lawn for $3. Still, this guy’s frightening.

“I’m just here to cover the Judas Priest trial,” I tell him.

“Three times,” he says angrily, “thou shalt betray me ere the cock crows.”

While I consider the wisdom of reminding Jacob that his quote concerns Peter, not Judas (Iscariot), he continues: “Oh, I’ll go to the cities. Salt Lake, Sacramento, Vegas. But I tiptoe through town. Satan’s walking proud.”

Pointing to the hotels’ 20-story skyline a block up, I begin to tiptoe away from Jacob. “He’s walking proud up there,” I say.

“No, that’s Mammon,” he says matter-of-factly, as though I’ve mistaken a crow for a raven. “Robbing, cheating, beating people up in the middle of the night’s no good,” I hear him say from 10 paces off. “It’ll come back to you, sooner than you think. Good and evil. Life and death. Gain and loss. The mountain cat’s joy”—he begins shouting—“and the deer’s pain. No pain, no gain. People who want something for nothing will lose their souls to Satan.”

Reno, depending on how your cards are flopping, might or might not be a town for Satan, but it is a town for losers. You see your first half-dozen before reaching the end of your plane’s disembark ramp, grim old ladies in bright holiday dresses, feeding the 25-cent slot machines at three quarters a pull. Downtown, the slots are mostly “progressive,” with red six-, seven-, even eight-figure jackpot numbers progressing faster than the eye can move on large digital displays above your head. Though it’s impossible not to see that these jackpot numbers are spelling nothing but the losses of millions of people, this is a fleeting awareness if you harbor the slightest conviction that life owes you anything. Within hours of landing in this three-square-mile city that, for no immediately discernible reason, sits in the middle of the Sierra Nevada mountain-desert range, you’ve learned to feel indignant, hopeful, and a little out of control every time you put a quarter in a pay phone.

To sit quietly for more than five minutes in most public places in Reno, be it a diner counter, casino lobby, or poolside at a $25-a-night motel, is to invite the person to your right or left to tell you his troubles.

By various estimates, 50 to 70 percent of the people living in Reno and Sparks, the adjacent bedroom community, have moved here within the last 10 years, helping to make Nevada the fastest-growing state in America in the 1980s. The migration pattern—families that have failed elsewhere and come here for a last chance—becomes clear quickly enough. To sit quietly for more than five minutes in most public places in Reno, be it a diner counter, casino lobby, or poolside at a $25-a-night motel, is to invite the person to your right or left to tell you his troubles. And, however dubious their confessions seem at first—the morose mechanical engineer who tells you, over third helpings of prime rib at the $10.95 buffet, how he was tortured out of his mind in Vietnam, the pretty jazz dancer who came out west with her gun-toting boyfriend from the Pine Barrens and became a 21 dealer—the statistics are there to back them up: Nevadans, “the last of the free thinkers,” have among the five highest rates per capita of marriage, cancer, heart disease, AIDS, alcoholism, prostitution, second mortgages, cocaine use by adults, divorce, churches, teenage covens, legal handguns and rifles, illegal handguns, murder, death-penalty cases, incarceration, child abuse, rape, single white mothers, teenage pregnancies, abortion, and successful suicides by white males ages 15 to 24.

Two “progressions” of that last statistic—Raymond Belknap, 18, by a sawed-off shotgun blast to the chin in a Sparks churchyard on December 23, 1985, and his best friend, Jay Vance, 20, who managed only to blow away the bottom half of his face—have led to what a Vegas bookmaker called the “biggest crapshoot” in Reno’s history: A multimillion-dollar product-liability suit brought by three local lawyers against CBS Records and the British heavy metal band Judas Priest. Seven “subliminal commands” (audible only by the unconscious)—all saying “Do it”—were allegedly embedded on a song on Judas Priest’s 1978 release, Stained Class, the album that was on Ray Belknap’s turntable the afternoon he and Jay formed their suicide pact. Coupled with four alleged “backmasked lyrics” (audible only when playing the record in reverse) on three other songs: the exhortations, “Try suicide,” “Suicide is in,” “Sing my evil spirit,” and “Fuck the Lord, fuck [or suck] all of you”—the Do its, say the lawyers, created a compulsion that led to the wrongful death of Ray Belknap and to the personal injury of Jay Vance. (Jay died of a methadone overdose three years after his suicide attempt.) The Belknaps are asking for $1.2 million, the Vance family for $5 million. “If you’re going to hurt someone,” one of plaintiffs’ lawyers tells me, only half-joking, “you’re better off killing them. It’s a lot cheaper.”

The suit was first brought in 1986 after Jay, in a letter to Ray’s mother, Aunetta Roberson, wrote: “I believe that alcohol and heavy metal music such as Judas Priest led us to be mesmerized.” Initially citing the content of the Stained Class songs “Heroes End” (“But you, you have to die to be a hero/It’s a shame in life/You make it better dead”) and “Beyond the Realms of Death” (“Keep your world of all its sin/It’s not fit for living in”), the suit seemed dead in the water after the California District Court of Appeals ruled that the lyrics of Ozzy Osbourne’s “Suicide Solution”—which had been cited in a similar suicide/product-liability suit—were protected by the First Amendment. Two copy-cat suits, for example—another California heavy-metal suicide and an Edison, New Jersey suit brought by the family of a 13-year-old who stabbed his mother 70 times and then flayed her face before killing himself—were dropped shortly after the Osbourne decision.

The Reno suit made its bizarre beeline into the unconscious a year and a half later, when six Sparks metalheads, hired by plaintiffs’ lawyers to decipher the lyrics of the Stained Class album, reported concurrent nightmares of going on killing sprees with semiautomatic weapons in neighborhood shopping malls. On the advice of Dr. Wilson Bryan Key, the godfather of the “subliminal expose” (his books, Subliminal Seduction, The Clam-Plate Orgy, Media Sexploitation, etc., have sold over 4 million copies), plaintiffs’ lawyers hired Bill Nickloff, a self-taught audio engineer who had achieved wealth and some local fame through the personalized subliminal self-help tapes he’d been marketing through his Sacramento firm, Secret Sounds, Inc. Examining a CD of Stained Class with his original “backwards engineering” process—by which he claims the audio signal of a piece of recorded music can be deconstructed into its component 24 tracks on his Mac II personal computer—Nickloff discovered the “smoking gun”: seven subliminal Do its in the first and second choruses of the song “Better By You, Better Than Me.”

Though he is never called to testify, Key is the genius loci of this suit. A 65-year-old Henry Miller look-alike with a MENSA belt buckle, huge forearms, and a young wife he is able to put to sleep with a posthypnotic suggestion, he lives 20 miles from Reno, off a highway running through surreal, sage-scented moonscape that yields the most exotic roadkill I’ve ever seen. We lose 15 minutes when I pull out my pack of Camels (and he tells me the subliminal history of the camel and the pyramid and palm trees it’s standing in front of), but he’s quick to point out that the issue of subliminals and the adverse (and actionable) effects of music are not without precedent. The Billie Holiday ballad “Gloomy Sunday,” for example, was banned from the radio in 1942 when several war widows killed themselves after listening. And the foreman of a jury in Pennsylvania cited subliminals as a mitigating factor in the 1989 guilty verdict for Steven Mignogna, a 19-year-old metalhead who murdered two 10-year-olds after listening to AC/DC, Ozzy Osbourne, Motley Crue, and Judas Priest for 12 hours in the cab of his pickup. Mignogna, who was defended by the Bishop of Sardinia (then in Pittsburgh for medical reasons), was given two consecutive life sentences rather than the death penalty the State asked for. Key served as an expert witness in that trial.

Key and Nickloff eventually concluded that the Do its had been uttered by a different voice than lead singer Rob Halford’s. Nickloff also speculated that they had been “punched into” (or layered beneath) the swirling chords of a Lesley Guitar, a backward cymbal crash, a tom-tom beat, and the prolonged exhalations of Halford’s falsetto rendition of the lyric

Better by you, better than me-ee-uh! [Do it!]

You can tell ’em what I want it to be-ee-uhh [Do it!]

You can say what I can only s-e-ee-uhh [Do it!”]

Nickloff also felt that enhancements of the Do its had been spread across 11 of the 24 tracks by a second machine, perhaps a COMB filter. He couldn’t prove this, however, simply by testing the CD.

Thus began a three-year hunt for the 24-track master tapes, not only of “Better By You” but of every other Judas Priest song, album, and rehearsal and live tape in CBS’s possession. The song left a long paper trail, and discovery of the 24-track proved far easier than other Judas Priest masters. The album’s only number not written by band members, it was recorded after CBS’s New York a&r men, who felt none of the album’s original eight songs had hit potential, proposed a list of “adds.” The list itself became a major piece of evidence, as the only songs highlighted for serious consideration by the a&r men were the Manson “Family” favorites, “Helter Skelter,” “Revolution #9,” and “I Am the Walrus”—the last two of which promoted endless fascination with backwards lyrics.

CBS located the master of “Better By You” in September 1988; they delivered a safety copy to Nickloff three months later—an “18-minute-like gap” that became plaintiffs’ second “smoking gun”: CBS, they alleged, had used the three months of studio time to cover up the embedded Do its. Nickloff asked for the original master, then refused to examine it when it arrived. The tape’s outer coating of zinc oxide, he said, had begun to flake (suspiciously, he thought), and he wouldn’t accept responsibility for it.

A series of motions and court orders regarding CBS’s cooperation in the search for other masters followed, leading to two and a half years of immensely mistrustful exchanges between plaintiff and defense lawyers. It degenerated into one of the ugliest, most contentious suits since Jarndyce v. Jarndyce: public accusations of complicity and conspiracy; shouting matches at prehearing depositions; detectives (including a former Scotland Yard man) digging into the silt of CBS corporate policy and procedure and the Oedipal dramas of plaintiffs’ families. It culminated in a 14-day trial that featured some exquisite dramatizations of humility, rage, bathos, incredulity, and condescension; Rob Halford’s a capella singing from the witness stand; enough repeated playings of his ee-uh! heavy breathings to make the court stenographer cover her face in shame; strident attacks, by CBS lawyers, on the existence of a Freudian unconscious and the work of Karl Meninger; a Manichaean courtroom divided between local born-agains and metalheads, and, on the last day of trial, disclosures of the professional lives of plaintiffs’ two principal lawyers, Ken McKenna and Vivian Lynch.

Courtroom melodrama isn’t something that bothers Ken McKenna. A likable, unabashed media animal (“My phone hasn’t stopped ringing since 1986,” he tells me), he’s responsible for the enormous publicity the suit has earned. The inevitable epithets—“tort twister,” “slip-and-slide man,” “ambulance chaser”—bring a bemused, faintly proud smile to McKenna’s face, and he’s not one to linger on the moral or emotional aspects of his cases. Not until closing statement time. Then he suddenly becomes pure corn, extremely fond of homespun similes, homilies (“I guess the lesson to be learned from all this,” etc.), and the words “gosh,” “sorta,” and “heck.” When the subject of his work comes up, his pudgy, angelic face (at 38, McKenna still looks like his high school yearbook photo) takes on a devilish grin.

“I was born to sue,” he says in the two-family house in downtown Reno he practices out of. “I didn’t know who or why or where or what I was till I discovered contingency law.”

At 8 a.m., sprightly during the first of several interviews he has scheduled for this Saturday morning, he looks like he’s just stepped off a budget cruise liner: blue shorts, salmon Polo shirt, a big smile on his well-scrubbed face, a solid gold Mickey Mouse watch on his right wrist. Stacked next to his Catalogue of Expert Witnesses are heaps of anti-heavy-metal pamphlets. While McKenna faxes a client, I leaf through one with an R. Crumb-like cartoon on the cover, Stairway to Hell: The Well-Planned Destruction of Teens. An epigram from Boethius—“Music is a part of us, and either enables or degrades our behavior”—prefaces a chapter on backmasked lyrics that focuses on the alleged backward content of Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” (“It’s just a spring-clean for the May Queen” = “I live for Satan. He will give you six, six, six,” etc.). Italicized in the first paragraph of text is the premise driving the ultra-right’s fascination with backmasking: Induction into the Worldwide Church of Satan is predicated on the ability to say the Lord’s Prayer backwards!

McKenna (who represents the Belknaps) and Lynch (who represents the estate of Jay Vance) deny identification with these anti-metal fanatics, but that Southern California-based fringe (known as the “Orange Curtain,” from their support base in Orange County) is very much behind the suit. Two of plaintiffs’ expert witnesses, Dr. Robert Demski, medical director of a San Antonio hospice for troubled adolescents, and Darlyne Pettinicchio, a Fullerton, California, probation officer, were recommended by Tipper Gore’s Parents Music Resource Center. Though their testimony—that Judas Priest’s music induces self-destructive behavior by glorifying Satan—was not allowed on record (Stained Class’s lyric content not being at issue), the metal link to the suicide would probably have not been made without them. It was through attendance at one of Pettinicchio’s seminars, or the reading of an anti-metal “police training manual” prepared by Demski, that one of the detectives handling the shootings knew to advise Ray Belknap’s mother to hang on to the Stained Class LP on his turntable.

“You can borrow that stuff if you want to,” McKenna says, putting a heavy, distancing accent on the word stuff. Walking me out to his porch after the interview, though, he can’t resist telling me that Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant “did, in fact, buy Aleister Crowley’s mansion.” (He’s not far off: Jimmy Page, Zeppelin’s guitarist, bought the Loch Ness estate, Boleskine House). I stop to look at an ornately framed photograph of the wreckage of a twin-engine plane in a copse of pine trees, given pride of place in McKenna’s front office. His head nodding with a connoisseur’s delight, McKenna admires the details of a splintered wing, caught in a bough some 20 feet from the plane, and the molten metal of the demolished cockpit and fuselage. That devilish smile comes to his face as he tells me, “That’s $2.2 million you’re looking at.”

Vivian Lynch, unlike McKenna, is a “lawyer’s lawyer.” A middleaged woman who speaks in perfectly constructed declarative sentences, she has a sober, battered look on her face, and pretty, penetrating blue eyes that become a rapid flutter of mascara and sky-blue eyeshadow whenever she concentrates on a point of law, cross-examines a witness, or addresses the court. Holder of the highest bar exam scores in Michigan and Nevada history, among the defense team she’s knows as “the dragon lady,” and three of their expert witnesses tell me how unnerving it is to be cross-examined by her. On both state and national amicus curiae committees, much of her legal work for the last two decades has been the drafting of other attorneys’ motions for the Supreme Court in Carson City. She entered the suit at the beginning of defense’s constitutional challenges in 1987, and has singlehandedly defeated every motion to dismiss, quash, and relocate that Reno and New York counsel for CBS have come up with.

“The histories of the Vance and Belknap families,” she tells me without batting an eyelash, “are certainly no different in kind or degree than what you’ll find across America.

Unlike McKenna, Lynch has no taste for publicity. She once left the suit for months when she felt that his media hijinks, particularly an interview given to the National Enquirer, had crossed over into the jury-prejudicial. She also seems entirely unmotivated by Mammon: A supporter of Tipper Gore, she’s “in this for my children,” two of whom were “extreme metalheads.” When she pulls up to her office for our interview, one side of her pickup’s flatbed is stacked with Diet Coke empties, and the passenger seat of the cab has a three-foot stack of legal paper. When a local Holy Roller, overhearing us discuss the suit in a restaurant, comes over with his two young daughters to testify that the “owner of a major U.S. record company belongs to the Worldwide Church of Satan,” and that his best friend’s brother jumped off the high bridge in Santa Barbara because of that company’s music, Lynch hears him out patiently, then gives her address so he can send his compilation tape of backward lyrics.

“I think that man’s insane,” I say when he shepherds his two daughters from the restaurant.

“I don’t,” says Lynch, draining her third iced tea. “I think he’s tripping. Didn’t you see how dilated his pupils were?”

Even if McKenna and Lynch can prove the existence of subliminals on “Better By You” to Judge Jerry Carr Whitehead (both sides agreed to forgo a jury), they still have to show those subliminals were the “proximate cause” of the suicide pact. CBS, arguing that Ray Belknap and Jay Vance tried to kill themselves because they were miserable, investigated the home lives of the boys, focusing on Ray’s mother, Aunetta Roberson (three husbands by the time Ray killed himself), the religious conflict in Jay’s life (his mother, Phyllis, is a born-again Christian, and Jay converted on several occasions), the alcoholic and allegedly abusive tendencies of both boys’ step- and adoptive fathers, and the bleak work prospects and fantasy-ridden lives of the pair once they’d dropped out of high school. The circumstantial evidence they uncovered is enormous.

By McKenna’s and Lynch’s own lights, however, the families of Ray and Jay were enviable. McKenna’s first case out of law school was the Murder One appeal of his brother Pat, for the slaying of a fellow prisoner while awaiting sentencing on a multiple-murder conviction. And though McKenna seems an extremely peaceable man (and is remarkably polite and gentle with hostile witnesses), he has no trouble improvising the most dramatic moment of the trial: a soliloquy of a father’s rationalizing thoughts as he beats his son (“I didn’t mean to hit him so hard”; “he was provoking me”; “I barely touched him”) that has the entire court’s heads bowed for over a minute. True to form, he prefaces the speech by placing a two-by-three-foot blowup of Ray Belknap’s tenth-grade yearbook photo on an easel facing the court.

“Following the defense’s logic,” says Lynch, “I should have killed myself 10 times over.” The eldest of three abused children, she and two younger sisters were taken from her parents when she was three years old. Institutionalized in a Long Island orphanage, after being sexually abused by another relative, at 14 Lynch moved her two sisters to Detroit, found a studio with a single Murphy bed, and went to work to support them. She entered Wayne State Law School on scholarship at the age of 19, held down a full-time job as a secretary (she can still take shorthand at 240 words per minute), and saved money by memorizing her textbooks and selling them back before classes started. She had three children of her own before her marriage ended with a divorce suit on grounds of abuse: “It took me a lifetime,” she tells me, “to learn that this wasn’t the way it’s supposed to be lived.” The divorce came through in 1972, four years after she had come home from a day of practicing law in New York, turned on the evening news, and saw her house being fired on by tanks with 9mm anti-personnel weapons during the Detroit riots. Six months pregnant, she returned to Detroit and was bayoneted in the back as she tried to enter her house.

In the 17 years since she moved to Reno, Lynch has raised seven children, her own and four from troubled households in her neighborhood. “The histories of the Vance and Belknap families,” she tells me without batting an eyelash, “are certainly no different in kind or degree than what you’ll find across America. I can say this for sure: They grew up like most of the kids around here.”

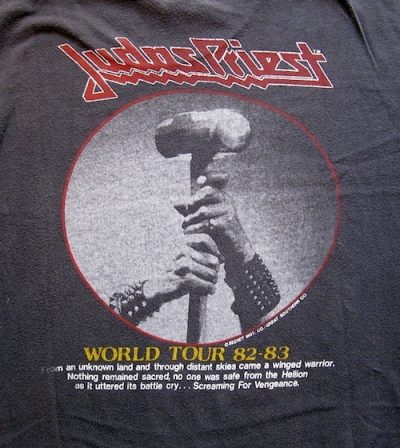

On South Virginia Street, you can lose a roll of quarters as you wait for your take-out order at El Pollo Loco or the Two Brothers from Verona House of Fine Dining, and the billboards are as likely to read: DIVORCE? WANNA MARRY? or HAVE YOU BEEN ABUSED?—followed by seven-digit numbers—as to announce Dolly Parton at the Sands, or next Saturday’s fight card at Harrah’s. Otherwise, South Virginia is a typical ten-mile burger strip leading out of town: small businesses, chain restaurants, mini-golf courses, teenage boys screeching their tires on Saturday night till they find a girl or a fight, and the occasional mammoth concrete structure, like the Reno-Sparks Convention Center, where Ray and Jay saw Judas Priest on their 1983 Screaming for Vengeance tour. It was a big tour for the band (the album was their first to hit platinum), and it meant a lot to the boys: Ray stole the six-foot tour poster—his stepbrother, Tom Roach, described it as a “mythic drawing, sort of a tank with a hull’s face, horns, y’know, missiles, guns”—and taped it above his bed for a year.

I drive to the Peppermill Casino, halfway out of town on South Virginia, to meet Scott Schlingheyde, a high school friend of Ray. A striking 21-year-old with long, immaculately blow-dried blond hair, he’s on parole after two years in the Carson City penitentiary (for selling crank, a methamphetamine), and has arranged this meeting place because he doesn’t want anyone to know he’s “back in town.” It seems like teenage vainglory: I can hear the Megadeth tape blasting in his yellow 1979 Le Mans from a block away.

Still, it’s sadly easy to forget Scott’s age when we sit in the hotel bar: He seems far more like some hardened and prospectless maqui—come down from some Philippine hill town to talk to a very foreign reporter—than any American teenager I’ve met. The only clues are his gape-mouthed appreciation of a 40-pound striper in the bar’s fish-tank, and a fit of uncontrollable giggling when I ask if it’s true Ray and Jay played Cowboys ’n’ Indians with live ammo. “Yeah,” he says finally, squelching his giggles by downing half a bottle of Bud, “that sounds like Ray.” When he speaks of guns, prison, child abuse, and suicide, he sounds like he’s talking last night’s ballgame.

“Ray and Jay weren’t all-out crazy, out-and-out violent people,” he says. “They did pretty much normal, crazy shit. We talked about suicide, all the time, but it was just tough-guy talk, normal weapons talk. They had normal problems. Maybe Ray had more than most.”

Scott stonewalls when I ask what problems: “He shelved that shit the moment he got out of the house, and I wasn’t allowed in there. Only Jay was. Those two were as close as you can get. I do remember one time, though, we went up to shoot my brother’s gun and Ray had to go get some clothes, ’cause he couldn’t go home. I think we ripped some beers on the way up.”

“What did you do at your brother’s house?”

“We did some crank, and shot some bottles.”

“Did Ray and Jay do a lot of drugs?”

“Anything that came their way. Anything they could afford. Mostly, drank a lot of beer. Beer was the only thing we could buy, underage, and it’s easier to steal than booze.”

“Did you guys steal most of the things you had?”

“No, no,” Scott shakes his head emphatically. “We bought our own cigarettes and music and beer. Mom bought the jeans and T-shirts. We never thought much about food.”

The only person Ray ever took to was Jay, whom he met in sixth grade. Jay, who had been left back twice, had BMOC status with his extra years, and his immediate love for Ray was an unending source of pride.

On the day of his autopsy, Ray, 6’ 2”, weighed 141 pounds, and the only thing in his stomach was a stick of chewing gum. He wore blue jeans over sweat pants, a gray MIAMI DOLPHINS SUPER BOWL ’85 T-shirt with sawed-off sleeves and vents cut out, brown construction boots, white tube socks, and a belt with a buckle shaped like a cannabis leaf. He had one tattoo, a green RB on his upper right arm (unlike Jay, who had many on his arms and upper body), and 25 small lacerations on his fists, from playing “knuckles” with Jay—punching each other’s knuckles to see whose bled first. Tom Roach testified that their stepfather, Jesse Roberson, would often take Ray to the garage, lock the door, and whip him with his belt until Ray could get the garage door unlocked and scamper to his room, but no indication of that or any beating showed up on the autopsy.

“Growing up,” Scott tells me, “Ray didn’t really have friends. He didn’t like anyone, and he didn’t like himself. He really hated his red hair.”

The only person Ray ever took to was Jay, whom he met in sixth grade. Jay, who had been left back twice, had BMOC status with his extra years, and his immediate love for Ray was an unending source of pride. Ray was never at ease with girls, unlike Jay, who would often find two girls waiting at his door when he came home from work. A pretty redheaded girl named Carol fell madly in love with Ray in tenth grade, and he left home for a week to live with her, but he could always be counted on to ditch her to spend the night with Jay. Their parents were gratified when the boys “showed their first sign of domesticity,” shortly after leaving high school: buying a pair of pit bull pups. Both dogs became ferocious after the shootings, and had to be put down.

Jesse worked at a Sparks auto-parts shop for $20/day plus commissions. Aunetta has worked for the past five years as a 21 dealer in a Reno casino for $35/night and tips. Ray, who was good with his hands (he made a shelf for targets he and Jay would take up to the hills with them), loved construction work. In his two years at Reed High, he flunked all but two classes: Shop I and Shop II. On his last application form, he wrote that he’d worked on a building site in Truckee, California, beginning as a day-laborer at $5.50 an hour and ending, a month later, as a $10.75-an-hour framer, but there’s no reason to believe this is true. His next job was at minimum wage, in a used furniture store. After three weeks, he stole $454 from his boss’s desk and left Nevada for the first time, on a bus to Oklahoma, to see his real father. A week later, however, he was back in Sparks, facing trial. He received a suspended sentence and, after much counseling, a generous probation that allowed him to leave the state and live with his father, on condition that he behave himself. It’s not known what happened to Ray in Oklahoma, but he was back in Nevada 10 weeks later, working the graveyard shift at a Sparks print shop. The job—feeding massive paper reams into a cutter—paid 10 cents above minimum wage. Two weeks before he killed himself, he was fired for refusing to work overtime when the morning man called in sick.

Ray liked to think of himself as a karate master and was very fond of his weapons: a sawed-off 12-gauge shotgun, a 12-gauge pump gun, a .22, a BB gun, a blowgun, and a two-foot-long, hard-rubber “whipstick,” whose purpose, as Tom Roach later testified, was simple: “It hurt when he hit you with it.” Both he and Jay were good shots, and when not stalking Tom Roach with BB guns through the house—for listening to “mellow” bands like Def Leppard and Night Ranger—would often spend weekends in the Sierras with their .22s, hunting quail, which Ray loved to eat spit-roasted. On work days, they went to a cave in the Sparks city limits, where they could “nail whole families of bats to the wall with air-rifle shot,” as Jay later testified. Ten days before the suicide, police came to Ray’s house on Richards Way to investigate a charge of animal torture: Ray had apparently shot the neighbor’s cat with his blowgun.

Other than the occasional trip to the mall or a night of playing “terrorize the town” on South Virginia, Ray’s only regular activity was up in his room with Jay, “listening to Priest” and fantasizing about becoming a mercenary. They loved Priest, Jay said later, because they got power from the music—“amps” was his word—and because their connection with Priest was more intimate than with bands like Iron Maiden, whose “‘Kill ’em all, let God sort ’em out’ sort of lyrics,” Jay said, “left us cold.” If they had a credo to live by, it was “Ride Hard, Die Fast.” In the hospital after the shootings, Jay used an index finger to draw the words LIFE SUCKS, when detectives asked why they had shot themselves.

Of the thousands of details that surface in the Judas Priest trial, two of the few that defense and plaintiff don’t dispute is that Ray and Jay loved Judas Priest more than any other band (in a deposition taken shortly before his death by methadone overdose in 1988, Jay said he “would have done anything those guys asked me to do”), and that the two boys were inseparable. Several friends testify that when they met Jay after the shooting, the first thing he would ask was if they blamed him for Ray’s death.

“I ran into Jay at a gas station one day,” Scott tells me. “But I didn’t know who he was till he started talking, ’cause he didn’t really have a face or anything. I couldn’t understand him either, because his tongue was gone. I was angry at him, though. There’s nothing in this world so hard you gotta shoot yourself over it,” he says, clenching his fists slowly, as though offering himself as proof. “Nothing.”

“What did you say to Jay at the gas station?”

“Nothing. Just walked away. I never saw him again.”

Growing up, Jay wanted to be a hunting or a fishing guide. Several early backpacking trips had a huge effect on him—in the Desolation Wilderness of northern Nevada, and, on visits to a favorite uncle up in Oregon, along the Pacific Coast Trail. He took up gardening work in junior high school and, never one to let reality get in the way of self-mystique, told his school psychiatrist he had a few landscaping companies and many investments in pieces of heavy equipment. As he began to realize he’d never make it through Reed High, his fantasy of enrolling in the Lassen Gunsmith College in Susanville evaporated; at the New Frontier drug program he lasted half of, trying to cure himself of a crank addiction, six months before the shooting, he spoke indifferently of becoming either a mercenary or janitor. He studied typing and applied science after the shooting, and had plans to become either a physical therapist, or, once his tongue was rebuilt, a suicide hotline operator.

“It’s like I always say: Either you worship Jesus Christ or you worship Judas Priest.”

Something went very wrong in Jay’s life in the first and second grades. One school psychiatrist called it “extreme hyperactivity,” another diagnosed him for Attention Deficit Disorder; he repeated both years. His mother refused to give him the nervous-system stimulant Ritalin, though it was strongly recommended by every doctor who examined Jay. “Those kids on Ritalin,” she says, “were zombies.” She agreed to see the district psychiatrist after Jay tied a belt around his head and began pulling his hair out one day in second grade, but refused to see the man when he came to examine Jay in the home environment. Driving home after being expelled for violent behavior in the third grade, Jay became enraged when his mother wouldn’t listen to his version, and wrapped his hands around her neck. Two years later, he went after her with a hammer, and with a pistol a few years later. From the age of 10 until he dropped out of high school in the first weeks of his junior year, he spent his school hours in the Special Ed Room with paraplegics, Down’s Syndrome kids, and the severely impaired (he remembered befriending one speechless boy who had swallowed a bottle of bleach at the age of three). He tested low on every proficiency and I.Q. test—his greatest problems being with hand-eye coordination—but Jay was hardly stupid. From the sharp, direct responses he gave in depositions after the shootings, one can see a quick-minded, intuitive, thoroughly ineducable kid who never had a chance in school.

From the age of 15, when he discovered Judas Priest, Jay had an album or song for every mood and period of his life: Unleashed in the East, when he wanted to get amped; Hellbent for Leather, to party; Screaming for Vengeance, when he left school and for nine months lived-in as a baby-sitter for an older woman. Both he and Ray loved the early album, Sin After Sin, with its cover: a black figure with no face. He said they listened to the songs “Epitaph” and “Dreamer Deceiver” when they needed to cry:

Saw a figure floating

Beneath the willow tree.

Asked us if we were happy.

We said we didn’t know.

Took us by the hands, and up we go!

We followed the dreamer deceiver.

“Jay recited those lyrics like scripture,” says Phyllis Vance, who agrees to see me once I swear I’m not from “one of those smut magazines like Enquirer, or Rolling Stone.” “Me and Tony [Jay’s adoptive father] would be watching TV in the living room and he’d be listening to Judas Priest in his bedroom, so loud that—through his earphones—we couldn’t hear the TV. And if I’d go in and tell him to turn it down, he’d point that finger at me, just like Rob Halford, and scream, ‘ON YOUR KNEES AND WORSHIP ME IF YOU PLEASE!’ After he was born-again, in 1983, he sold all 13 of their albums to Recycled Records. He stopped doing drugs for a while too. It’s like I always say: Either you worship Jesus Christ or you worship Judas Priest.”

Jay later said it was Priest’s music that turned him, temporarily, into a white supremacist. His high school guidance counselor, Susan Reed, sent him to the infirmary in his sophomore year when the swastikas and Judas Priest logo he’d drawn with black magic marker on his left arm had caused a serious infection.

The 23rd of December, 1985, a freezing, overcast day, began for the Belknaps with a family trip to the Happy Looker hair salon in the shopping mall off Richards Way. Ray’s four-year-old half-sister, Christie Lynn, was getting her first haircut; Ray went home to get a camera, and on the way back to the Happy Looker decided the time had come, after years of wearing his long hair back in a bandanna covered with Priest logos, to have it cut into a manageable buzz—especially while his mother was paying.

Ray was in a good mood. He’d lost his first paycheck in three weeks over a few games of pool at a local tavern the night before, and all but one installment of the $454 he’d stolen from his former boss was still owed, but he had enough money to buy Christmas presents for everyone. Not one to stand on ceremony, he opened the records he’d bought (including the hard-to-find Stained Class LP he’d bought for Jay) when he got home from the Happy Looker. Rolling a joint, he thought about Jay’s plan to get the paycheck back from the contractor he’d lost it to: “I was going to stomp on him in the back of his knee, and then crunch his knee to the concrete, karate chop him in the back of the neck, and he would pretty much be helpless at that moment,” Jay later testified, “’cause I know karate.”

The day had begun for Jay shortly after noon. In a deposition given under hypnosis two years later, he remembered that he “woke up, saw my death, and looked around.” He cleared his eyes, had a piss, took a glass of chocolate milk from the kitchen to the bathroom, and drank the milk slowly as he sat under a hot shower for a half-hour. Then he put the glass on the toilet seat and washed his newly buzzed-cut hair.

He’d stayed too long in the bathroom, and missed his ride to the print shop, where he worked the second shift as an apprentice. His mother had left a note in the kitchen: She was at her sister’s house, and wanted Jay to call if he needed another ride. Jay, however, couldn’t find or remember his aunt’s number. Perhaps he didn’t want to: He hated his 12-hour shifts, which left him so filthy it took up to three hours to scrub the print-ink off his forearms.

Reaching behind his stereo for the Stained Class album, he put the disc on the turntable and gave the jacket to Jay, saying, “Merry Christmas, brother.”

Ray was baby-sitting Christie Lynn and a few of her friends all afternoon, but he had time to pick up Jay in his mother’s car, then stop back at the Happy Looker to get his hair recut to look more like Jay’s. They drove back to the ranch-house on Richards Way and, in Ray’s room, put on Unleashed in the East and The Best of Judas Priest. After a spat over the two joints of “scrub-bud” they were smoking (Jay was angry Ray “stoled the pot from a friend of mine”), they got to work on their first six-pack of Budweisers. They left the room an hour later, Ray to tell his sister and her little friends he was going to bust their fucking heads if they didn’t stop running around and slamming doors, Jay to get some more beer from the fridge in the garage. In the dining room, he ran into Ray’s pregnant, un-wed half-sister, Rita Skulason, who was yelling at Ray to stop messing with the kids. She scowled at Jay as he came in holding the beers. Rita hated Jay, which bothered him (he was used to girls fawning over him), but today he didn’t care: He was feeling good, having come to the decision that he would no longer be a printer’s apprentice. He told Rita that if his mother called, she should say he’d already left the house and was walking to work. Rita couldn’t wait for Phyllis’ call. She knew it was the only way to get Jay out of the house.

Ray had a big smile when Jay got back to the bedroom with the beer. He’d also made a big decision—not to wait until the 25th to give Jay his present. Reaching behind his stereo for the Stained Class album, he put the disc on the turntable and gave the jacket to Jay, saying, “Merry Christmas, brother.” As the opening lyric of “Exciter” played; “To find this day/We’ll surely fall,” Ray and Jay stood up and hugged and punched each other, then started dancing around the room, playing air-guitar and punching the walls.

They listened to both sides two or three times (depending on which of Jay’s depositions you read) before going back out to the garage for more beer. Rita was still sitting at the dining room table. She later testified Jay came over and fondled her breast, but Jay denied that: “Rita wasn’t the kind of girl you could do that to. She’d bust you in the mouth.” Perhaps they were a little drunk: When Ray killed himself, two hours later, his blood-alcohol was a hundredth of a point below legal intoxication. They might have already considered suicide: Jay asked Rita if she would name her baby after Ray if anything happened to him. “Not unless it’s a goddamn redhead,” she said.

Half an hour after they returned to Ray’s room, Jay’s parents were at the Belknap’s front door, to drive Jay to work. They were too late. “I was rocking out,” Jay later said. Phyllis tried to reason with him, asking, “How are you going to buy your cigarettes if you don’t have any money?” but she and Tony were out the door a minute later. Jay a foot behind them, screaming, “LEAVE ME ALONE!”

Jay wedged a two-by-four against the jamb as Ray grabbed a pair of shells and his favorite weapon, the sawed-off twelve-gauge, and opened his bedroom window and crawled out.

It’s not clear how many more times they listened to Stained Class, or which song was on when Jay told Ray, “Let’s see what’s next.” In one deposition, Jay said the lyric, “Keep your world of all its sin/It’s not fit for living in,” finally led them to understand the message they had been “struggling all afternoon to understand”: “The answer to this life is death.”

Ray seemed to understand immediately and said “Yeah,” offering his knuckles. They rapped fists together until it was too painful, then began to trash the bedroom, smashing and slashing everything except Ray’s records, mirror, bed, and two burlap sacks, stenciled 50 KG—MEXICO, that hung over his guns in the corner of the room. The kids down the hall started crying, and Rita Skulason made an emergency phone call to their mother, who immediately left her 21 table at the casino and drove home. They were still going strong when she pulled into the driveway, ran to the bedroom door, and began calling Ray’s name. Jay wedged a two-by-four against the jamb as Ray grabbed a pair of shells and his favorite weapon, the sawed-off twelve-gauge, and opened his bedroom window and crawled out.

By the time Jay had followed out the window, Ray was already 20 feet down the alley behind his house, a few feet shy of the six-foot concrete wall of the yard of the Community First Church of God. Jay yelled at him to wait, and the two scaled the wall together. At 5:10 p.m. on the third shortest day of the year it was already pitch-black in the churchyard, and Jay had no idea where they were. A neighborhood dog had begun to bark, and they were worried about the police coming. Neither was old enough to be outdoors with a loaded gun within the city limits. It was well below freezing, and both boys were wearing only jeans and T-shirts.

Ray gave Jay a shell, then stepped onto a small, rickety carousel in the comer of the churchyard and loaded up. He looked terrified as he heard the gun cock. In depositions taken a few months later, Jay remembered saying, “Just hurry up” to Ray; in his later testimony, he also remembered Ray beginning to spin around on the carousel, chanting “Do it, do it” for four or five circles. In his first hypnotic deposition, taken almost three years later, Jay remembered that his last words to his friend were “Just do it.”

As the years went by, Jay’s memory put him further from Ray’s suicide. In all but one of his later depositions, he testified he had his back turned when Ray pulled the trigger. In the year after the shootings, he could remember seeing Ray kill himself only in a recurrent nightmare—inaccurately: In the dream, he would see fire coming out of the back of Ray’s head—a memory, plaintiffs lawyers claim, not of the shootings, but of the Stained Class album cover, which shows an android’s silver head pierced by a laser-like beam that flares up as it exits the skull.

Two days after the shootings, however, Jay told detectives he watched Ray stop the carousel and plant the gun on the ground between his feet. The coroner’s report located the entrance wound in the exact center of Ray’s chin, confirming Jay’s memory that Ray had the gun barrel “so tight under his chin his voice was clipped when he said, ‘I sure fucked up my life.’” He reached down for the trigger and squeezed it with no hesitation. The shot imploded inside his skull, causing no exit wound and little disfigurement. It sprayed the carousel, the gun, and a square yard of ground in front of the carousel, however, with “an incredible amount of blood.”

Jay remembers “shaking real bad” as he picked up the gun from the ground, uncocked it, and put the shell Ray had given him into the chamber. “I didn’t know what to do,” he said. “I thought somebody was going to stop me.” He told police he only went through with his half of the pact because he was afraid of being accused of Ray’s murder. When he tried to put the gun end into his mouth the blood on it made him gag, so he put it under his chin, then stood next to the carousel for an uncertain amount of time, thinking about “my mom, and people I cared about.” He eventually heard the siren of a police car responding to a call from a neighborhood woman about the first shot—which, by the police dispatcher’s log, puts him standing frozen with the gun held under his chin for over five minutes. When he heard the siren he tried to steady the gun; its barrel, trigger, and nose felt greasy from the blood, however, and Jay’s hand-to-eye coordination failed him one last time as he slowly worked his hand down the barrel for the trigger. The shot took off his chin and mouth and nose, missing his eyes and brain as it exited just above his high cheekbones.

He remembered a tremendous weight leaving him as he dropped to his knees and fell face-first to the ground, then a long numbness, followed by a stinging sensation, as though someone had slapped him. “Then somebody [a paramedic] turned me over on my back… and checked out my blood,” and he “fought with that person to get back” onto his stomach, though he never could remember why he did. As he was tied to a stretcher and placed into the ambulance, choking on blood and fragments of his face, he was given an emergency tracheotomy, and he remembered the strange sensation of having his throat cut into and feeling no pain. He had no idea that his teeth and tongue and palate were gone, and he couldn’t understand why the simple sentence, “I don’t want to die” wouldn’t come out when he tried to say it to the paramedic.

The buffets broadcast from the hotel marquees get cheaper, the entertainers get older, and the hold ’em games go from $1-3-5 to $3-5-10 as you drive from Reno to Sparks. A suburban sprawl crawling up the northeastern ridge of the Sierras, Sparks extends higher and seemingly at random with each year into the canyons and mountain hillocks: endless streets of one-story houses with one willow or evergreen on each lawn, a car or two in each driveway, and one four-wheel-drive vehicle, RV, or big boat in front of every other house. Most of the four-wheelers, RVs and even the boats have gun racks in the back windows.

Four doors down from Ray’s old house on Richards Way, I find the yard of the Community First Church of God. A 20-square-foot patch of grass surrounded by six feet of cinderblock (interrupted only by a chain fence on the east wall), it looks more like a prison yard. Formerly a playground for Sunday school kids, it has a spooky, cloistered feel to it. The peeling, whitewashed cross on the church roof is visible between two immense weeping willows overhanging a brace of swings; only one swing is still on its chain. Two feet from the sawed-off stump of a third willow is the small foot-pump carousel Ray was sitting on when he shot himself.

The worst of Jay’s endless nightmares after the shootings were filled with Christian symbolism of slaughtered animals and stained glass. There is no such glass visible from the yard where the boys shot themselves, but there are three cheap panels of stained glass on the front of the church that would give anyone nightmares. The last bears a striking resemblance to the Stained Class album cover: a faceless, purple and mauve Christ Ascending that has the head of Christ being penetrated by one of the metal rods connecting the glass.

Jay lay in the hospital for three months, receiving daily injections of morphine and listening, he later testified, to Stained Class, playing over and over in his head. When he couldn’t take it anymore, he got a friend to make a tape of the album and played it for weeks, trying, he said, “to get the music out of my head” and “to bury my grief for Ray.” Once he got accustomed to his morphine dosages, his feelings of guilt kept him from falling asleep. “It’s so weird,” he said, “saying goodbye to someone.”

Jay was in constant agony for the last three years of his life: Coupled with the initial trauma, the skin extenders pulling on the flap of forehead caused massive swelling and chronic infection.

The extent of the reconstructive surgery was enormous. Doctors at Stanford University Hospital began with the only piece of facial skin remaining, a flap of forehead, attaching skin extenders to pull it gradually down and across the area, leaving the greatest bulk in the center, to become a nose. The skin grew hair and had to be shaved daily. After two years, a surgeon began working on a pair of lips from skin taken from the smooth crease under the knee, and Jay was halfway toward his third and final chin—bone fragments from the back of his right shoulder blade—when he died. A third of his tongue remained, but he’d lost his gag reflex when the back of his palette exploded, and he drooled and swallowed his tongue. He had only one tooth, and he ate by using his thumb as a second incisor. When he went to watch McKenna and Lynch work on an unrelated trial, he was ejected from the courtroom for upsetting the jury; when the six-year-old daughter of another lawyer saw him on an elevator, she screamed for a few seconds and then fainted.

Jay was in constant agony for the last three years of his life: Coupled with the initial trauma, the skin extenders pulling on the flap of forehead caused massive swelling and chronic infection. He survived numerous addictions to prescribed Percodan and Xanax, and often said that he hadn’t known what a “real drug addiction was like” when he checked into the New Frontier program for crank abuse in July of 1985. The Percodan and Xanax were nothing, however, compared to his abuse of cocaine, which he began injecting into his arm to ease the pain. (Though he’d always hated needles, he no longer had a nose to snort the coke through.) He was up to two grams a day before he overcame the addiction with weekly nerve-block injections—two-inch needles in the base of his neck. To qualify for Tony’s insurance (to pay for what he called his “$400,000 face”) he stayed with his parents. Incredibly, his love life didn’t slow down: He turned down two offers of marriage, and an old girlfriend—who came to live with the Vances after her stepfather booted her out of the house on her 18th birthday—bore a child of Jay’s a year before he died. “I told them I didn’t want them monkeying around in the bedroom,” Phyllis recalls. “Jay said I forgot to mention the garage, the front lawn, the backyard…”

Despite being placed on suicide watch in Washoe Medical Center on Thanksgiving Day, 1988 (Jay got enormously depressed every year around the holiday season), he died of a methadone overdose on December 2, a few hours before he was due to return home. The death was listed a suicide, but it isn’t clear how he got enough of the drug, not only to kill himself, but to reduce his brain matter to a substance the Washoe District Coroner described as “gelatine.” Phyllis Vance is convinced it was the hospital’s malpractice: “Jay felt he had everything to live for. He used to say that he was literally reborn after the accident.”

Jay put his mother in the hospital on two occasions after the shootings—both, she tells me, during seizures of cocaine toxicity and withdrawal agony: He split her lip the first time; the second time he fractured her nose. “But we were never closer than after the accident,” Phyllis Vance tells me over Diet Cokes in her backyard, where we’ve come because she won’t let me or Tony smoke in the house. “Jay’d wake up screaming in blind terror in the middle of the night, and I’d be lying right there beside him. It was literally blind terror. His face was so swollen he couldn’t see anything except his dream, the same one, night after night: Ray blowing the back of his head off and the fire coming out.”

Tony, sitting beside her, lights a Marlboro and nods his head. I ask if he’d like to respond to reports that Jay’s was a violent home. “I remember one time,” he answers with a flat, emotionless voice, “when Jay came back from California with his eyes all glassy. I told him, ‘Show me your eyes,’ and he wouldn’t. So I went into his room to punish him. He said, ‘Daddy, I’m too old for you to be spanking me.’ So, I haul off and belt him, two or three times, with my fist. I don’t know if it did any good,” he says, “’cause I never did it again.”

Tony is a Blackfoot-Cherokee from Kentucky, a quiet, handsome man with jet-black hair, broad shoulders, and huge hands that have a slight but constant tremor. He never seems at ease, either in his backyard or in the courtroom, where defense lawyers continually refer to his alcoholism and gambling, and repeatedly cite the evening Phyllis pulled a gun on him to stop him from gambling his overtime pay. The tremor in his hands becomes more pronounced when he tells me he didn’t drink until the Oakland GM plant he drove a forklift for closed down in 1979, and that he didn’t gamble until they moved to Nevada. “And that gun thing only happened,” Phyllis explains, “because Tony was used to gambling with his overtime money, which is only fair. After the accident, though, we needed all of it for Jay.”

“The one thing I’ll never be able to get over, though, is that he did it in a churchyard, without even knowing where he was.”

Phyllis is a short, stocky, enraged-seeming woman with a high, strident voice and piercing stare. Though she’s not an easy person to get along with, after an hour of talking in her backyard I’m able to see her for what she is: a powerful, angry woman who, five years later, finally knows why her son shot himself. She now works for a Christian organization, counseling suicidal teenagers. “The one thing I’ll never be able to get over, though,” she says, truly mystified, “is that he did it in a churchyard, without even knowing where he was. Piece by piece, though, you put it all together, and you can finally stop asking yourself, ‘Why? Why?’ It was the subliminals.” I nod my head and try to concentrate on what Phyllis is telling me, but my eye keeps wandering across her yard. But for a few tons of concrete Tony laid down for Jay’s pit bull to run in, it looks exactly like the churchyard of the First Community: a 20-foot patch of grass bordered by a six-foot wall, two big weeping willows overhanging a brace of swings that has only one chain swing left. A few feet from where we sit is the sawed-off stump of a third willow.

When we go back into her living room, there’s a repeat episode of “Geraldo” about covens on the 25-inch TV, and Tony sits down to watch. “We’ve seen this one already, Tony,” Phyllis says, turning the volume down so she can listen to a long message on her answering machine. It’s from a young woman in Hidden Valley, near Carson City, calling about the suicidal condition of a 15-year-old girl she and Phyllis are counseling. “She had returned to Christ, Phyllis,” says the young woman. “But I have to say she seems very desperate now.”

By the last week of the trial; the horde of metalheads protesting outside the courthouse has dwindled to a few aging stoners with goatees and Motorhead and Houses of the Holy T-shirts and one 90-pound girl wearing white pumps, a white bustier, and jeans with a copper zipper that goes from front to back. Their tinny cries of “Let the music live” are drowned by the right-to-life pamphleteering of a slack-jawed scarecrow of a man named Andy Anderson, who’s been running for lieutenant governor of Nevada for three decades. “I still haven’t found the right man to share the ticket with,” he tells me.

Of the 75 media people who had come here from seven countries, the three networks, four cable channels, and the major newsweeklies and dailies, only four rather cynical stringers for the wire services and local papers, some local TV and radio people, and a documentary team from New York have lasted the first week of the trial, which has become extremely technical. Three-quarters of the testimony given is from “expert witnesses”—psychologists, audiologists, and computer experts—many of whom seem to have confused their testimony for Oscar-acceptance speeches. “We had a suicide shrink here last week,” one stringer says, “who thanked everyone in the Yellow Pages for his long career. He was so deadly the bailiff was talking about putting speed bumps by the exit.”

The 83-seat courtroom, no more than half-filled till the last day of trial, is noticeably devoid of metalheads, whose attendance was successfully dissuaded by Judge Whitehead’s strict dress-code order after the second day of trial. Other than Phyllis Vance (who comes every day, accompanied by a visionary-looking black-haired man dressed in impeccable linen), there are very few magic Christians here, born-again or otherwise: a fascinated 15-year-old girl with strawberry blonde bangs, who sits behind me telling her rosary; the man whose friend’s brother jumped off the Santa Barbara bridge; and one very anxious elderly woman, wearing the same emerald pants and midnight-blue shirt every day, who seems poised to rise and object to every question posed by defense’s lawyers. (On the last day of the trial, she finally stands to say, “Please stop this! I have 25 children that I work with downtown and someone has to care for them. Someone has to stop this.” As she’s led out, she pleads with Judge Whitehead, “Oh, please put me on the stand, Your Honor. I’m an electronics expert.”) The empty jury room, formerly needed to handle overflow press, has been given over to defense’s entourage for recess breaks: U.S. and U.K. management people, producers and recording engineers, a few CBS corporate types, two very jolly 275-pound security toughs from Tempe, Arizona, Rick and Nick, who have the entire defense team addressing each other with “Hey dude,” and the four forty-something members of Judas Priest, the band one recent critic called the “doyens of heavy metal.”

The tour included whips, industrial-grade smoke machines, fire pits, flamethrowers and a 15-foot robot that shot stadium-length laser beams and lifted the two guitarists, Ken Downing and Glenn Tipton, 20 feet into the air during lead breaks.

After a first decade of opening shows for the likes of AC/DC, UFO, and Ratt, Priest has been on a roll since their 1980 release, British Steel, which earned them a hardcore metal following. Like Spinal Tap (the parody metal band based largely on Priest) they’ve been accused of glomming from every trend imaginable: the guitar pyrotechnics, dry-ice smoke, mythic-medieval themes, and onstage monsters of Deep Purple, Black Sabbath, and Jethro Tull; Kiss’s two-tiered stage sets and multilayered leather costumes; and the hell-oriented themes that bands like Venom, Mercyful Fate, Scorpions, and Megadeth hit gold with by reaching the various covens and Satanic wannabees in the U.S. and Europe. Led by lead singer Rob Halford (who began as a theater apprentice in Birmingham and only switched to metal, he tells me, when he realized he’d “stay in the limelight longer that way”), they have worked their way into the heart of heavy metal: show biz. First they shed heir 1970s kimonos, velvet robes, and buckskin boots for leather, studs, spurs, and choke collars; then they began riding onstage on Harley-Davidson two-tone Low Riders; by 1985, the tour included whips, industrial-grade smoke machines, fire pits, flamethrowers and a 15-foot robot that shot stadium-length laser beams and lifted the two guitarists, Ken Downing and Glenn Tipton, 20 feet into the air during lead breaks.

Skip Herman, “Morning Mutant” deejay of Reno’s metal station, made friends with the band in the early days of the trial and began hanging out with them in the mountains near Lake Tahoe, where Priest has rented a suite of deluxe cottages. Over and above a mutual love for music, he and Priest share a guiding passion: golf. “They talk about the trial for the first two or three holes,” he says, “then maybe a little music, girls, a lot of old times. Ian [Hill, the bassist] and Glenn talk about their kids. From there to the clubhouse, though, it’s nothing but setting up a good, steady tripod with your legs, and establishing that perfect pendulum for your swing.” Skip invites me to his radio station to hear a slew of reverse-direction lyrics he’s found, his favorite being Diana Ross’s “Touch Me in the Morning,” on which I clearly make out the chant: “Death to all. He is the one. Satan is love.” I ask him to play Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” in reverse. Every word of the “I live for Satan” chant is perfectly audible.

“It’ll be another 10 years before I’ll even be able to spell subliminals,” Ken Downing says as he signs autographs on the way into the courtroom on the last Monday of trial. Rob Halford and Tipton, however, don’t see the joke. “It’s terribly wrong, you know,” says Tipton, “for my family to have to turn on the tube, see this poor kid with his face blown off, and have the finger pointing, ‘Judas Priest did this.’ I have a lot of guitar work to do, but you can’t go around to court every day, sit down behind your lawyers, have the knife twisted in your gut for eight hours, then go home and pick up your axe.”

“These people act like we drink a gallon of blood and hang upside down from crucifixes before we go onstage,” Rob Halford says. “We’re performers, have been for two decades. Do the show and wear the costumes our audience expect us to.” Halford is a complex man: extremely polite and soft-spoken, with a thick working-class Birmingham accent and bright, caricatural droopy eyes, he has a dry, caustic wit that makes everything he says, sees, and hears seem in doubt, in contempt, and in quotes. The trial, he admits, “is good publicity,” then quickly adds. “It’s been murder on my creativity as an ar-r-tist, though. I can’t wait for it all to end. I’m going to explode when this next tour begins. Legal proceedings are so-o frustrating.”

He’s the only band member who seems to pay attention to the proceedings: grinning widely at the clipped King’s English spoken with enormous largesse by half of defense’s witnesses, several of whom are Australian; at the boastful testimony of a Dr. Bruce Tannenbaum (Jay’s psychiatrist in his last two years) that he is “the only white man ever to have endured the Native American fire-sweat ceremony”; as an advocate for subliminal self-help, who claims his tapes have been documented to promote hair-growth, enlarge breast size, cure homosexuality, and “to’ve turned a local college’s worst football season in its history into a division contender” (a wide receiver from the team is also called, to verify). Halford seems in awe of a Toronto psychologist who’s called in by defense to recite the entire “Jabberwocky” section of Through the Looking Glass backward (he’s finally instructed by Judge Whitehead to stop), and deeply touched by the testimony of five friends of Ray and Jay, who contradict reams of evidence as to their whereabouts on December 23, 1985. One glassy-eyed kid, whose testimony places Ray in his pickup an hour after the suicide, is asked by Whitehead to show his eyes to the court, then quickly dismissed from the stand.

Whitehead’s eyes betray nothing. An austere Mormon with a quiet but pronounced sense of his own dignity, he seems like a man who has grimly determined he will catch more flies with honey than vinegar. Whether sustaining or overruling an objection, he delivers his rulings with exactly the same measured deference, consideration, and inaudibility. (Several times a day he is asked by defense lawyers to repeat his ruling.) His courtroom has a statewide reputation for running by the book and to the minute. Entering each morning at precisely 8:45, he says, “Thank you, please be seated,” and clears his throat away from the microphone. But for an occasional question from the bench and visible winces when witnesses refer to the “backmasked lyric” “F—— the Lord” as “Fuck the Lord” (after 11 days of trial, Whitehead still listens to that section of tape with his face averted from the court), he sits impassively till 5 p.m., then whispers the day to a close without the slightest clue as to what he’s seen, heard, or thought.

After Lynch files a Motion in Limine (asking to be awarded the decision outright, on the basis of CBS’s lack of cooperation in producing evidence) and a Motion for Sanctions (money), the first three days feature endless declarations of the utter impossibility of “punching” anything into mixed-down two-track or 24-track tape, then of CBS’s hopeless task of locating those tapes—probably the first two times in American legal history an arts corporation has argued for its lack of control of the matrix of production. Two mornings and afternoons are devoted to some very unconvincing testimony as to the scarcity of both types of backward lyrics: phonetic reversals (lyrics that form a sensible fragment when played in reverse) and backward-recorded reversals (words recorded forward, then added to the mix in reverse direction). After eight court-hours of testimony (by men who engineered and/or produced such records as Electric Ladyland, The Wall, the first four Zeppelin albums, and Her Satanic Majesty’s Request, which has an entire song in reverse), a 32-year-old engineer/producer named Andrew Jackson (called to testify because he served as assistant engineer on the “Better By You” recording session, 13 years ago) is asked if he knows of any backmasked lyrics in the rock industry.

“I’ve never known such a lull in me bloody sex-life. I don’t think I’ve had an erection since we’ve got here.”

“Yes I do,” he says with a Cockney accent so thick Judge Whitehead asks him to deliver his testimony while facing him. “In fact, just last month I produced a band had a song with the lyric, ‘And I need someone to lie on/And I need someone to rely on.’ Played in reverse that becomes ‘Here’s me/Here I am/What we have lost/I am the messenger of love.’“ The singer, Jackson testifies, memorized the backward phrase, with all its reversals of sibilants and plosives, then sang it on a track that was used—backward—as a forward-running vocal overdub.

“And do you know of any instances of backward-recorded lyrics in the rock industry?” he was asked as CBS lawyers covered their faces.

“Why, yes, I do,” Jackson says. “A Pink Floyd song I worked on has a lyric: ‘Dear Punter. Congratulations. You have found the secret message. Please send answers to Pink Floyd, care of the Funny Farm, Chalford, St. Giles.’”

I get to hear the alleged Do its when court adjourns to a 24-track studio across town on one of the last days of the trial. Two stringers have harrowed grimaces as we enter a darkened room that, through a two-inch plate-glass window, looks onto the engineering console the court is reconvening in. “We were in Carson City last month to report on a death-penalty execution,” one explains. “It was set up just like this.”

From the four-foot UREI Studio Monitors in our room I hear the title cut’s first chorus, played—to Whitehead’s consternation—forward first:

Long ago, when man was king,

This heart must beat, on stained class

Time must end before sixteen

So now he’s just a stained class thing.

It’s followed by the reverse of the next line, “Faithless continuum into the abyss”—the alleged “Sing my evil spirit.” It is a creepy sound, inhumanly high-pitched and strangely clipped and emphatic: “S-s-eeg maheevoh s-s-speeree.”

Whitehead asks to hear the reverse of “White Hot, Red Heat”—because it confirms the “message” of the song when played forward, the “desecration” of “The Lord’s Prayer”:

Thy father’s son

Thy kingdom come

Electric ecstasy

Deliver us from all the fuss…

I only hear what sounds like an evil dolphin chanting, “F-f-f-fuck thlor-r-r-r’, S-ss-suck-ck tolleyuse-se-se.”

“Better By You, Better Than Me” is the kind of Priest song Jay said he and Ray most loved: “a steady, galloping rhythm… only changing for the chorus, [when] the beat would get more dramatic or more intensified.” After the screeching lyric:

Tell her what I’m like within

I can’t find the words, my mind is dim

The first chorus comes, with its prolonged ee-uh exhalations. I don’t hear anything that sounds like Do it, but there is an extra, syncopated beat falling after the third beat of each measure, a disco-like mesh of noise that has nothing to do with the musical or lyrical content of the song. It does sound—if not “punched in”—added on.

As the song moves into the second chorus with the lyric:

Guess I’ll learn to fight and kill

Tell her not to wait until

They find my blood upon her windowsill

The extra beat seems to land with greater emphasis, more elaborated and groan-like with each ee-uh sound, until I hear the words Do it—as a kind of antiphonal chant—falling, with relative clarity, on the last rendition of “You can tell her what I want it to be.” Far less clear is Halford’s rendition of the lyric itself. In his screeching desperation, it sounds far more like “You can tell her what I wanted to be.” All I can think of is Ray sitting on the carousel, saying, “I sure fucked up my life.”

The issue of backward masking seems resolved forever on the last day of testimony. Halford, absent from court all morning, arrives late in the afternoon with a large, black double-deck and a cassette. Put on the stand, he says that he’s spent the morning in the recording studio, spooling Stained Class backward, and would like to play what he’s found for the court. Ever the showman, he asks if he can play the tape forward, sing the lyric once, play that “backmasked stuff,” then sing that.

Lynch objects furiously to the tape’s admission, and to Halford’s request to perform for the court. Whitehead agrees there’s no need for Halford to sing again, then cracks his first smile of the suit. “I want to hear this though.”

“Some of these aren’t entirely grammatical,” Halford deadpans apologetically. “But I don’t think ‘Sing my evil spirit’ would’—

“Objection,” says Lynch.

“Sustained,” says Whitehead.

A blast of heavy bass and Tipton’s 32nd-note trill accompanies the fragment, “strategic force/they will not,” from “Invader.” Its reverse is the insane-sounding but entirely audible screech: “It’s so fishy, personally I’ll owe it.” When Halford plays, “They won’t take our love away,” from the same song, the backward, “Hey look, Ma, my chair’s broken,” has the courtroom howling. Lynch and McKenna are livid.

After a week of suspending disbelief, I lose it when Halford plays his last discovery, in which the rather Mighty Mouse-ish chorus of “Exciter”:

Stand by for Exciter

Salvation is his task

comes out backward with the emphatic, high-pitched

I-I-I as-sked her for a peppermint-t-t

I-I-I asked for her to GET one.”

The band is exultant after Halford’s performance. Up in their Reno counsel’s offices, Ken Downing and Ian Hill are talking of issuing a Greatest Hits album, Judas Priest: The Subliminal Years. Their American manager is on the phone booking Tipton’s family on a morning flight to the Grand Canyon, and Halford, giving an interview to the New York documentary team, is saying, “I’ve never known such a lull in me bloody sex-life. I don’t think I’ve had an erection since we’ve got here.”

I ride down with Ian and Ken to the bar in Harrah’s, where both they and their drink orders are well-known by the maitre ’d. The two original members of the band (they dropped out of their secondary school in Birmingham in the same year), and the only two that don’t seem compelled to shower plaintiffs’ every statement with scornful smiles, they watch the proceedings with a mixture of curiosity and incomprehension till the late hours of afternoon, when they both look ready for a long nap and a stiff drink. Over second Bloody Marys, I tell Downing I’ve noticed that his ears seem to prick up every time Ray and Jay are mentioned. A 38-year-old man with a shoulder-length permanent, deeply receding hairline, a slight paunch, and a tendency to repeat the words “You know?” when he tries to explain anything, he seems fascinated when I say I’ve been to the churchyard where the shootings happened.

“Will you take me?” he asks, then grimaces. “Maybe that’d be in bad taste, eh? I’ve got strange feelings about those kids. It’s not guilt, you know, but I do feel haunted when I hear about their lives, because they were the same as mine. I hated my parents, you know, terribly. These kids just didn’t get to live long enough to put all that past them.”

“So you made up with your parents eventually?”

”Oh, I talk to my Mum all the time.”

“Is your father dead?”

“No, he’s alive. But I don’t talk to him. I don’t hate him anymore, though, you know? I don’t feel that I really matured till I stopped carrying that anger around with me, and that wasn’t till a year or so ago. The music was the only real release, till then. I do feel angry, though, when they play all that backward surf music and talk about the harm we did these kids, ’cause I think our music was the best thing they had, you know? I remember citing sophisticated stuff verbatim to my folks—like they say Jay did—Jimi Hendrix lyrics, like, and they’d look at me, like, ‘Where’s all that coming from?’ You know? My parents aren’t clever people, you know? They’re just normal people.”

“I’ve got strange feelings about those kids. It’s not guilt, you know, but I do feel haunted when I hear about their lives, because they were the same as mine. I hated my parents, you know, terribly. These kids just didn’t get to live long enough to put all that past them.”

Halford and Tipton, finished with their interview, arrive with the security guys, Rick and Nick. On our way into the three-star restaurant, Rick is arguing with Nick about Nevada’s other major court case—the libel suit brought by the Las Vegas Stardust Hotel against the animal rights group, PETA. “Some dude slaps an orangutan around a little,” says Rick, “and they ask for $800,000,000.”

I don’t remember much of that dinner, but I’ll never forget the next morning’s hangover. Between repeated calls for “one more bottle of this Chateau Neuf-de … POP!, Captain Bong,” to our Filipino headwaiter, Halford, who sat at the head, regaled the table with recitations from his favorite Mafia movies, then led a backward-sounding finger-chorus by everyone at the table on our Diamond Optic crystal wineglasses. Rick and Nick ordered the Chateaubriand for Two, apiece, and the argument began raging again when Nick told Rick he must have plaintiff and defendant confused in the Vegas case. “It would have to have been the animal rights guy who slapped the orangutan. It’s the Stardust that’s suing.”

Ken, who sat to my left, ordered a second appetizer instead of an entree—“I’m worried about fitting my stage clothes,” he confided—and told me how he hated secondary school. “I was all thumbs in Woodworking Shop. Metalworking, which is a biggie in Birmingham [several members worked for British Steel before joining], was even worse. The only thing I liked was Chess Club. I got to beat up on those kids with the perfectly pressed uniforms. And Cooking.”

“Why Cooking?”

“’Cause you got to watch the girls bend over. I went to work as a cook after I left school, and I loved it, you know? Still do. I mean, how many people do you know, even at this age, who can bake an egg? You know?”

Some time between the third bottle of Moet and the warmed Grand Marnier, I remember a silver plate with an $800 check hitting the table. “Happy Verdict, Captain Bong” was written on the back.

Judge Whitehead’s decision on both the suit and Vivian Lynch’s Motion in Limine and motion for sanctions was handed down two weeks after the end of the trial. An impressive document, it runs 68 pages, stopping en route to cite Sir Edward Coke’s 17th century interpretation of the Magna Carta and Thomas Paine’s and James Madison’s arguments for the right to trial.

After criticizing CBS’s actions in the discovery process, he awarded plaintiffs’ lawyers $40,000. Finding (1) that the 24-track of “Better By You” submitted by CBS was authentic and unaltered, he declared (2) that there were several Do its; (3) that they were subliminals; (4) but they were placed on the record unintentionally; (5) and that lack of intent establishes lack of liability under invasion of privacy theory; (6) that plaintiffs established a sufficient foundation for the effectiveness of subliminal stimuli, and that the decedents did perceive these; (7) but that plaintiffs failed to prove these stimuli were sufficient to explain conduct of this magnitude; and (following a lengthy disclaimer of any intent to demean the Vance and Belknap families); (8) that a number of other factors existed to explain the boys’ behavior.

Whitehead’s other findings concerned backmasked messages, which he rejected out of hand. Though he had “grave concerns” over their possible use if perceived by the unconscious, he found no reason to believe they could be so perceived. And though he indicated his displeasure with heavy metal, several times, he closed by thanking the members of Judas Priest for their courtesy during the trial.