Peter Beard is trying to organize another expedition. This one promises to be far tamer than any of the African safaris, walkabouts, and fact-finding missions he’s pulled off as cameraman, artist, adventurer, playboy, doomsayer, nature-lover, metaphor-tracker, and, ultimately, one of the world’s great photo opportunists. But it couldn’t possibly be any less complicated.

Beard wants me to meet in Manhattan with “Elizabeth of Yugoslavia” (as he refers to the socialite princess), and then limo with Charlie the chauffeur out to his place in Montauk, Long Island, to spend the night. The next morning we’ll head for the wilds of Harvard University, where they’ll be knee-deep in elephant politics. Anthropologist Richard Leakey, director of Kenya’s Department of Wildlife Services (where Beard’s other home is located), is scheduled to speak on a panel with some heavyweights in the as-go-the-elephants-so-goes-man debate. It is a subject that has obsessed the 52-year-old Beard for more than three decades and has been the subject of some of his most gruesomely beautiful photographs: those of desiccated elephants in a Kenyan national park, killed not by poachers but by starvation after being “protected” from any agents of mortality.

Even though I’ve never met Peter Beard—he’s just a resonant voice on my answering machine and a ruggedly handsome face in a stretched-out mock turtleneck in The Gap ads—I already feel pulled into the Peter Beard Experience. The PBE is the process by which Beard takes the world’s problems, meshes them with his own personal problems—all of which have been artistically raised to “metaphor” status—and then magically and charmingly turns them into your problems. It is a calculated frenzy of immediacy—which even his agent admits “upsets the shit out of some people”—that he regularly whips up for his myriad friends in High Society, High Concept, Haute Couture, Macropolitics, and Big Science. He captures their attention, provokes their thoughts, eats their food, and records their interactions with him in his massive art-diaries—collages of photographs, ghostly rubbings from magazines, newspaper clips, writings, blood, and, lately, fragments of Beard’s crumbling teeth—before handing out Xeroxes from his apocalyptic clipping service and moving on to the next creative feeding ground.

“I’m telling you,” Beard says, his deep voice Eric Sevareid-insistent, “this is going to be very heavy, a once-in-a-lifetime experience, not to be missed. We are totally doomed, and this is like Darwinism being debated again. The elephants are a metaphor; ecologically, they’re the closest species to man. Go read the afterword to [the 1988 edition of] The End of the Game. Those five pages sum up everything. Overpopulation is the key to everything. That’s why food aid produced megafamines. Bob Geldof was knighted for his activities. He caused the problem. More food means more people. The ability to feed more people is the most dangerous thing he could have come up with.

“But I’m telling you, don’t miss this debate at Harvard. It’s heavy. It’s the whole thing. It’s the sentimentalist fund-raisers with their ‘buy an elephant a drink’ crap against the experts on population dynamics. We cannot conserve any of the big game or wilderness areas, and the next thing we’re going to fail at is us.This debate is about why. I anticipate Leakey getting his ass wiped.” Leakey, son of the famed anthropologist Louis Leakey, who championed the “missing link” theory, is caught between the American charity-driven effort to ban ivory and elephant-skin sales as a way to stop poaching and “preserve” elephants, and the population experts who are simultaneously searching for “management” techniques to cull herds efficiently. Beard is a hard-core management fan, although he is an artist, not a scientist—“a chronicler,” explains one friend, “not an action person”—and he seems ultimately less interested in solving the problem than creatively restating that the end is near and that everything commonly believed about wildlife and the environment is wrong. He is, as he says, “heavily into beating a dead horse.”

But the trip is having a number of hitches. For one thing, Charlie the chaffeur is having marital difficulties. (“You know, it’s bad enough that she’s divorcing me, but to throw me out of my own place … Christ,” Charlie says to me, interspersing our phone conversation with obscenities lobbed at the above mentioned wife). Over much of the twenty-four hours preceding our presumed rendezvous, Charlie and Beard call numerous times, giving me not very practical instructions and details. First, the Montauk leg is canceled because Charlie’s court date with his wife got changed and Elizabeth of Yugoslavia isn’t sure she can go at all. Then Beard wants me to fax the afterword of his first book, The End of the Game, to a population expert in Connecticut. (Beard doesn’t own a copy of his document of the beginning of the end of Africa, published in 1965 and recently reissued.) Finally, I get a midnight call from Beard saying that Charlie is nowhere to be found and that the whole thing is off. But a message on my answering machine the next morning is that Charlie has “totally come through,” and that we’re to meet at P.J. Clarke’s at 11:30 a.m.

At this point, I call Beard at seven to tell him he’s on his own for this one, whereupon he shifts gears and quickly gives me the number of his business manager. “Call him at 9 o’clock and tell him to tell the bank that I’ll need to take out some money this morning,” he says. “Just make sure there’s some money there to take out, okay? Now, I gotta catch my train into town. Okay, bye.”

At 9 a.m., I am placing a long distance call at my own expense to arrange the financial affairs of a man I’ve never met.

A week later, Beard tells me to come to New York for a rendezvous at the Chelsea apartment of “a real pal, Mauritzio, who’s been letting us crash at his place.” When I show up, I am informed that Beard is, as usual, expected at any moment but still at lunch with an old friend, photographer William Wegman. This information comes from Najma Khanum Beard, a stunning, personable Afghani woman in her early thirties who Beard met in Kenya (her father was a high-court judge there) and who is his third wife—not to mention his thousandth gorgeous companion, if legend tells correctly. Najma is also the mother of his first (and, he says, “accidental”) contribution to the world’s population problems: one-year-old Zara.

“The whole world is a scab. The point is to pick it constructively.”

While awaiting the return of Peter—or “PB” as his wife refers to him—we chat. The family is leaving for Europe and then Kenya in a few weeks, and many of the arrangements can’t be made from Montauk. Najma is negotiating what appears to be a touchy visa situation, while Peter tries to schmooze up enough work to cover his travel expenses and the massive legal fees being generated by a suit that grew out of what was to be the first of many ABC specials. (Professional hunter turned wildlife sculptor Terry Mathews, an old bush buddy of Beard’s, was brochetted by a rhino during the filming of the special, and when the footage was used in the show, he sued, causing Beard legal headaches and causing the network to shelve plans to finish the series.) Beard has already lined up a gig for Forbes documenting desert elephants in postwar Namibia and one for Cosmopolitan shooting three models in cat suits prancing around live elephants in Kenya. But he’s still looking for a sponsor for a traveling multimedia presentation that, he says, “will totally save my ass, financially; otherwise, I’m just totally broke.”

Najma is charming company, but after an hour passes we’re all wondering about PB’s whereabouts. Najma tries to track him down with a few calls, but to no avail. At the two-hour mark, I decide to cut my losses and try to track Beard down another day.

I finally meet him a week later in the same apartment. Dressed in a flannel shirt and an African kikoi skirt, he’s talking into a cordless phone, busily trying to unsnarl the complications revolving around Naj’s visa.

Between phone calls, he hands me a copy of Longing for Darkness, his tribute to his heroine, Karen Blixen, a.k.a. Isak Dinesen, whose Out of Africa first drew him to Kenya. Beard had formed a close relationship with Blixen, who eventually agreed to let him document her life and gave him the rights to her story, which he wrote with the help of Blixen’s lifelong servant Kamante (who provided recollections and drawings).

“Read the introduction to this,” he says, dialing another number, “it’ll explain a lot.” But before handing it over to me, he rips through the pages, coming to a letter from Jackie Onassis included in the book’s afterword. “Can you believe that after all the work I’ve done I needed a letter from Jackie to get this book published?” he says. “Good of her to do it, though. Oh, hi, French Embassy? Peter Beard here. I have a situation I hope you can help me with. I am, well, what’s the best way to explain this …?”

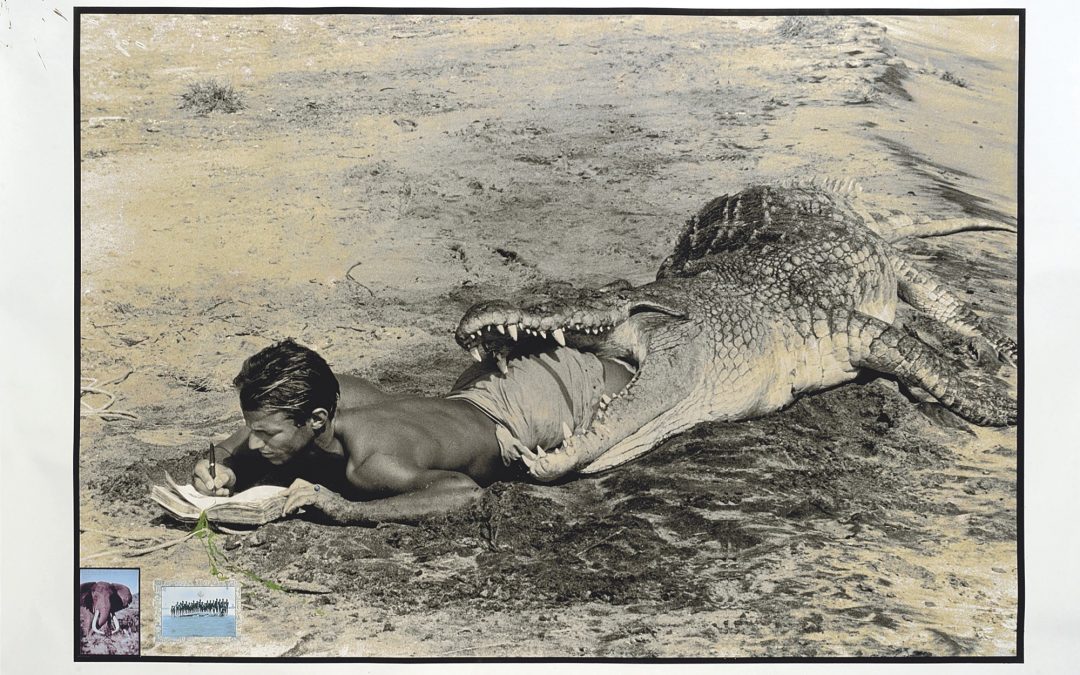

Peter Hill Beard both defies explanation and begs it. Bred for success into an aristocratic New York family and schooled at Pomfret and Yale, he discovered Africa and photography as a teenager in the ’50s. By the mid-’60s he had figured out a way to combine his two obsessions (and various laws of the jungle) into a self-sustaining avocation that would allow him to escape actual vocation. With his sharp eye and excellent social contacts, he had formed relationships with Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar that brought him fashion photography assignments and access to the media. He had also gotten to know Blixen, as well as some of the leading scientists studying Kenya and the political figures ruling it. While photographing life in Africa, Beard also worked for two years with scientists studying the elephant population in Tsavo National Park in Kenya, spent a year in Uganda studying elephants and hippos, and then studied crocodiles under the auspices of the government of Kenya (taking the photos used in Eyelids of Morning, written by wildlife expert Alistair Graham). His work and celebrity led the then president of Kenya to waive the rule prohibiting foreigners from buying land: Beard was given a special dispensation to spend part of his trust fund on the forty-nine-acre Hog Ranch outside of Nairobi, abutting Blixen’s property.

But Beard rarely stayed put, shuttling back and forth between the wild kingdoms of Kenya and New York and the various party capitals of Europe, where he observed and documented all manner of jungle behavior and animal husbandry. During this time, Beard parlayed his unconventional lifestyle, photographic prowess, and animal magnetism into a book contract with Viking to create The End of the Game—part documentary and part diary, part jungle story and part biological nightmare. Its 1965 publication solidified Peter Beard’s international reputation as more than just a rich kid on a walkabout. It also crystallized his mission: to document both natural beauty and its vulnerability to annihilation, to create photographic artifacts that could be used to sell products or geopolitical viewpoints, and, ultimately, to be Peter Beard. The book also improved his status as a tourist attraction in Kenya—taking exotic pictures of top model Verushka with her body painted, playing host to international socialites who wanted to touch rhinos. And his 1967 marriage to Newport society girl Minnie Cushing fortified his ties to civilization.

By the ’70s, when People magazine started bringing the world of the “beautiful people” to the less-beautiful masses and transformed gossip into hard news, Beard’s fixturehood reached the public. His Montauk home was where Dick Cavett, Andy Warhol, Truman Capote, Caroline Kennedy, and the Rolling Stones (of whom he made some of the first rock videos) often visited. His Kenya home was where the jet set went to get high, get naked, and get funky. He was linked romantically with Lee Radziwill, Candice Bergen, and nearly every model with whom he did test shootings. He was a Studio 54 regular, and he was always enormously quotable: “The whole world is a scab,” he once told Newsweek. “The point is to pick it constructively.”

“Like a lion in a zoo he was careening toward a civilization because it seemed like the right thing to do, and then the lawyers set in.”

At the same time, Beard’s work—which he (and some critics) insisted was “subject matter … not photography”—was receiving a reevaluation of sorts. In 1977 the International Center of Photography in New York mounted a show of Beard’s pictures and his multimedia (photos, etchings, writing, human blood) diaries. Doubleday published a redesigned edition of The End of the Game, updated to show that the cautious optimism the first version had was totally unfounded. The elephants in Tsavo hadn’t been saved—in blurbing the book, Nobel laureate Norman E. Borlaug called the mismanagement of African land a “wildlife Watergate”—and the ecosystem of the park itself had been totally destroyed, turning a rich woodland into a virtual dustbowl.

In the meantime, Beard’s unconventional lifestyle had become more the convention. Tribal bacchanalia was in vogue; the macabre and the mysterious were beautiful. But living this wild life for two decades, instead of the requisite fifteen minutes, had already taken its toll. Beard had been arrested in Kenya for assaulting and “unlawfully confining” a poacher discovered on his land (Beard was convicted and was imprisoned for ten days before protests led to his release and an eventual retrial with a more favorable result). He had overdosed on drugs in 1969 and was institutionalized for five months. His wife had divorced him. And in 1977 he had lost most of his possessions—including a priceless collection of pieces given to him by artist pals and twenty years of his own diaries—when an accidental fire destroyed his Montauk home (where, he later found out, his insurance had lapsed). All of this shaded a lengthy profile of him that appeared in Rolling Stone in November of 1978. The piece was written by Doon Arbus, daughter of the late photographer Diane Arbus, and it came as no surprise that she saw Peter Beard as a self-destructive image-collector in the heart of darkness.

There are those who believe that Peter Beard never left the discocaine mutiny era, which was highlighted in 1978 by his legendary fortieth birthday at Studio 54 (everyone was there when they lowered the elephant cake from the ceiling) and in 1981 by his marriage to top model and poster girl Cheryl Tiegs. “I think that the person who is still alive and who exemplifies that period greater than any person I have ever known is Peter Beard,” says one current top model. “He has devoted his life to basically living in the manner of the fashion world from 1978 to 1981. He travels around the world, he is constantly dealing with where the money is, and he is constantly surrounding himself [with] models. To me, he is like a living monument of that time. He is also a publicity-monger, which is also the mentality of the time.”

Beard speaks of those days wistfully. “That was the last hurrah for New York,” he says. “Studio was a phenomenon; every night was like a Fellini party. Everyone was there and you could do whatever you wanted there. Steve Rubell was responsible for some of the last good times in the city. They had to put him in jail to stop them.”

The careerist ’80s weren’t a comforting place for a nomadic throwback like Beard—it was more the era of his older brother, a managing director at Morgan Stanley. He managed to maintain his place in both the gossip headlines and the scientific debates, but, to some, Beard had gone from shaman to charlatan. “Decided to go to Peter Beard’s party at Heartbreak,” Andy Warhol had dictated to his diarist in late 1983. “Peter was at the door showing slides. The usual. Africa. Cheryl on a turkey. Barbara Allen on a turkey. Bloodstains. (laughs) You know.”

And then what was left of his heyday caved in. After working together on Tiegs’s much-publicized clothing line, their marriage went down in flames. Beard is still not legally allowed to discuss the divorce—the conditions of a certain escrow account assure that he won’t until 1993—but his finances and spirit were clearly decimated by the experience. “I think that’s when it first came thudding home to him,” says his manager, Peter Riva. “Even an intellect as massive as his has to have a moment when he can’t cope anymore. Like a lion in a zoo he was careening toward a civilization because it seemed like the right thing to do, and then the lawyers set in. I think it changed him, as did simply getting older. He’s a little more open to realizing that if he wants to cope psychologically with living on this planet he has to do some things that aren’t always fun. He knows he’ll take photographs for an assignment, and some editor will make them look incredibly ugly. He’s resigned to it. On the other hand he’s suffering fools less lightly. Before, someone could do something bad to him and he’d slap the guy on the back and say he’s a great friend. Now he’s admitting it when people piss him off, which surprises all the people who never knew where they stood with him.”

Then Out of Africa was finally made into a film—without him. Beard initially had director Sydney Pollack’s ear, but later he became a prominent outcast from the filming of a story to which he still claims to own the rights. He was planning a somewhat different version of Blixen’s life, with a screenplay by himself and Truman Capote and music by the Rolling Stones. He calls the finished film “a totally California plastic package … if Karen Blixen were alive, she’d commit suicide over that movie.”

Spread out on the floor amid his own turmoil, is Peter Beard, doing what he does best: holding court.

But, by the time the film came out, Beard had far bigger problems. Drained by the divorce, he returned to Kenya to find himself under attack from several fronts. The first husband of Iman (Beard had discovered her and launched her modeling career) went to the Kenya Times with a story about how Peter Beard had destroyed his marriage and tried to murder him. Then Blixen’s servant Kamante, who lived with his family on Beard’s land, grew gravely ill; when he died, his family announced that Beard had bilked them of their share of the profits from the Longing for Darkness book and insisted that they were owed half of Beard’s property. Finally, Beard was arrested twice: first for growing marijuana, then for trafficking in pornography (a museum-exhibition catalog from a Helmut Newton retrospective). Beard believed he was being harassed by Kenyan officials who wanted to confiscate his land. He eventually pleaded guilty to one charge and was acquitted on the other counts. But, in an ironic twist that he would later elevate to “metaphor” status, he could only pay his legal fees on the pornography charge by taking an assignment from Playboy and then convincing Iman and Janice Dickensen to come to Kenya to pose nude with some crocodiles.

The situation was further complicated because Beard had met Najma Khanum, a Muslim whose father was a high court judge in Kenya. Najma began working with Beard, doing research on his books and for the company he was starting with Iman to market African kikoi skirts in America. When he and Najma became romantically involved, her father had her “locked up for six weeks,” says Beard, “in the great Muslim tradition. Then he tried to have her committed through the local hospital. The doctor was a pretty nice guy, knew that Naj was totally sane and just a victim of Muslim fundamentalism. He tricked the father into letting her out of the country. She went to Germany, to her father’s brother’s place, and through Elizabeth of Yugoslavia I was able to contact her.” Eventually they came to America, where they were married in December of 1986.

But the New York he returned to was an increasingly serious place, less tolerant than ever of people without clear job descriptions, less interested than ever in experimentation of any sort, since spontaneity can increase overhead and decrease profits. Nobody went out anymore, nobody used drugs anymore, and lots of people who had been gay weren’t even gay anymore. AIDS had taken many of the fun people and scared the rest into sitting at home watching videos. Fashion photographers and models who once aspired (at least occasionally) to “creating moments” that might be captured on film, now just got paid lots of money to make pictures as quickly and “professionally” as possible. At the height of Studio 54, he had grown fond of invoking Karen Blixen’s observation that when the wildlife was gone, the only comparable thrill might be found in the middle of the biggest cities. Now even that thrill was gone.

It’s lunchtime at Elizabeth of Yugoslavia’s, where a small group has gathered (with their shoes removed) to discuss African wildlife, rehash the Leakey debate, network, and, ultimately, indulge in the Peter Beard Experience. On the couch of the small penthouse apartment sits Noel Brown, director of the North American office of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and Graham Boynton, an editor to whom Beard is pitching a story about the “Easthampton enviro-Nazis” who are preventing him from rebuilding part of his home. Najma Beard is smoking a cigarette, perched halfway out the sliding glass door to the small terrace in Smoker’s Purgatory Position—cigarette-holding hand and fume-blowing lips extended into the icy winter air while the rest of her lithe body tries to retain needed heat. Dashing between a humming fax machine and a sumptuous luncheon spread is the cheery Princess Elizabeth herself. And spread out on the floor amid his own turmoil—the strewn contents of a straw bag including Xeroxes with cryptic messages written on them and a two-foot-high leather-bound ledger book that is his 1989 diary—is Peter Beard, doing what he does best: holding court, spreading the gospel of overpopulation, generating sympathy and assignments for himself, and getting a free meal.

Leakey, it turns out, didn’t get his “ass wiped” at all. He came out at Harvard talking about “management” instead of “preservation,” and to Beard that one word speaks a thousand pictures. Preservation has come to connote the efforts to keep certain animals alive at any cost—even to the animals—and has led to such actions as bans on hunting and ivory sales and, more recently, the July 1989 burning of 2,500 confiscated elephant tusks to dissuade poaching. Management has come to connote an overview of the problem based on population dynamics: namely that species protected from “agents of mortality” will overproduce, die of starvation, and destroy their habitat in the process. Furthermore, selling animal skins and tusks is natural and the only way animals can “pay for themselves.” (Proponents of this side often point out that the African word for animal also means “meat.”)

Preservation to Beard represents “sentimentalism based on Walt Disney anthropomorphism perpetuated by animal do-gooders who want to see Joy Adamson French-kissing milk into her lion cub’s mouth. And you should’ve seen who these people were in the audience at the Leakey debate. The fund-raising little old ladies in tennis sneakers—and, you know, many of them are right-to-lifers. But when you’re fund-raising you milk any cow that hobbles along and that’s the heart of the sickening puke-lie right there.”

The battle over the big problem is, of course, waged over the tiniest issues. All assembled agree that Leakey’s use of the word management is a huge step, although he also supported the ban on US ivory purchases organized in part by the so-called International Tusk Force. The value of the ban was challenged by one of Beard’s heroes, Richard Garstang of the Endangered Wildlife Trust of Southern Africa. But the ivory bonfire is Beard’s obsession. He stops all conversation in the room to insist that Noel Brown make a quotable pronouncement on the event.

“I think,” Brown says, “that the bonfire is an obscenity.”

“Did you get that?” Beard turns to me and asks, “Did you get that quote? That’s a major, heavy quote. Noel Brown? Head of UNEP? Heavy quote. Trust me.”

When the conversation begins to slow—the issues are so clear, the solutions so vague, and Beard, whatever his intentions, tends to magnify the hopelessness, “the galloping rot,” above all else—lunch is served. And then to the videotape. Beard has to meet with his lawyers later today to discuss strategy in his suit, so he needs to borrow Elizabeth of Yugoslavia’s videotape of the Mathews flinging. It is particularly brutal footage. Mathews tries to shout off the rhino, which appears to have been distracted by some tourists in a bus off-camera, and then falls to the ground when the rhino gets close. Then, inexplicably, he stands up again, allowing the rhino a clean shot at his body. In one quick motion, the rhino impales Mathews through the leg and throws, him high into the air.

As the lunch winds down and Brown needs to head back to the office, the topic of Peter Beard doing an exhibit in the UNEP gallery is raised. Beard happily accepts the offer, which he adds to the growing pile of work that has built up: the magazine assignments, his ongoing book project From a Dead Man’s Wallet (which will feature his diaries, his least-known and arguably most significant art), and an update of Longing for Darkness that will include the saga of his arrest and continuing battles with the Kenyan government.

Brown leaves and Beard begins packing up his stuff. Boynton pulls out two copies of The End of the Game and asks Beard to autograph them—one for himself, one for Richard Leakey (go figure). To execute his autograph, Beard must go into the bathroom, so the blood-red ink with which he makes his trademark palm print won’t get all over the carpeting.

As we all shuffle out, Boynton and I share a cab downtown. As we ride, he explains that he has often considered doing a story on Peter Beard himself. But he feels he couldn’t write such a story without making some concrete assessment of what effect Peter Beard has actually had on elephant politics. And that, unfortunately, is difficult to say: even though his photographs are often used as visual aids in the war on poaching, he is rarely quoted in any of the numerous articles that have recently appeared on the elephant problem and, if truth be told, he wasn’t actually invited to the Harvard debate. He just wanted to be there, wanted to see it: the endless discussions about the limo ride no different than the jeep techniques he’s developed to misdirect animals’ attention in the bush (he and his assistants roll out of the still-moving vehicle). “I’m not sure I’d really want to quantify what it is he’s actually accomplished,” Boynton says. “But he certainly is an amazing character, isn’t he?”

[Photo Credit: Peter Beard via Christie’s]