One afternoon in the late 1970’s, deep in the labyrinthine interior of a massive Gothic tower in New Haven, an unsuspecting employee of Yale University opened a long-locked room in the Payne Whitney Gymnasium and stumbled upon something shocking and disturbing.

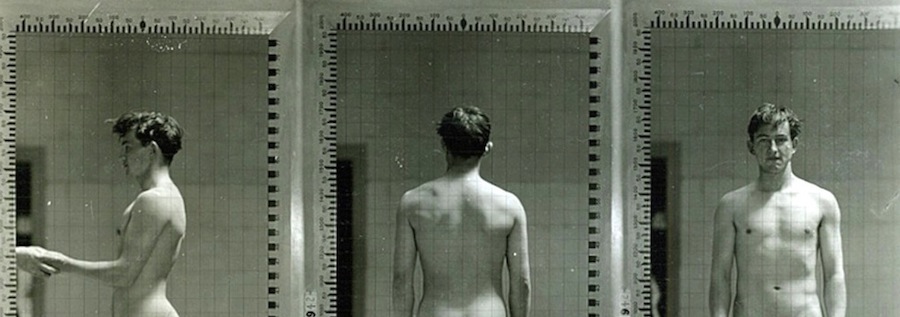

Shocking, because what he found was an enormous cache of nude photographs, thousands and thousands of photographs of young men in front, side and rear poses. Disturbing, because on closer inspection the photos looked like the record of a bizarre body-piercing ritual: sticking out from the spine of each and everybody was a row of sharp metal pins.

The employee who found them was mystified. The athletic director at the time, Frank Ryan, a former Cleveland Browns quarterback new to Yale, was mystified. But after making some discreet inquiries, he found out what they were—and took swift action to burn them. He called in a professional, a document-disposal expert, who initiated a two-step torching procedure. First, every single one of the many thousands of photographs was fed into a shredder, and then each of the shreds was fed to the flames, thereby insuring that not a single intact or recognizable image of the nude Yale students—some of whom had gone on to assume positions of importance in government and society—would survive.

It was the Bonfire of the Best and the Brightest, and the assumption was that the last embarrassing reminders of a peculiar practice, which masqueraded as science and now looked like a kind of kinky voodoo ritual, had gone up in smoke. The assumption was wrong. Thousands upon thousands of photos from Yale and other elite schools survive to this day.

When I first embarked on my quest for the lost nude “posture photos,” I could not decide whether to think of the phenomenon as a scandal or as an extreme example of academic folly—of what happens when well-intentioned institutions allow their reverence for the reigning conjectures of scientific orthodoxy to persuade them to do things that seem silly or scandalous in retrospect. And now that I’ve found them, I’m still not sure whether outrage or laughter is the more appropriate reaction. Your response, dear reader, may depend on whether your nude photograph is among them. And if you attended Yale, Mount Holyoke, Vassar, Smith or Princeton—to name a few of the schools involved—from the 1940’s through the 1960’s, there’s a chance that yours may be.

Your response may also depend on how you feel about the fact that some of these schools made nude or seminude photographs of you available to the disciples of what many now regard as a pseudo-science without asking permission. And on how you feel about an obscure archive in Washington making them available for researchers to study.

While investigating the strange odyssey of the missing nude “posture photos,” I found that the issue is, in every respect, a very touchy matter—indeed, a kind of touchstone for registering the uneven evolution of attitudes toward body, race and gender in the past half-century.

UP YOUR LEGS FOR YALE

I personally have posed nude only twice in my life. The second time—for a John and Yoko film titled “Up Your Legs Forever,” which has been screened at the Whitney—I was one of many, it was Art, and let’s leave it at that. But the first time was even more strange and bizarre because of its strait-laced Ivy setting, its preliberation context—and yes, because of the metal pins stuck on my body.

One fall afternoon in the mid-60’s, shortly after I arrived in New Haven to begin my freshman year at Yale, I was summoned to that sooty Gothic shrine to muscular virtue known as Payne Whitney Gym. I reported to a windowless room on an upper floor, where men dressed in crisp white garments instructed me to remove all of my clothes. And then—and this is the part I still have trouble believing—they attached metal pins to my spine. There was no actual piercing of skin, only of dignity, as four-inch metal pins were affixed with adhesive to my vertebrae at regular intervals from my neck down. I was positioned against a wall; a floodlight illuminated my pin-spiked profile and a camera captured it.

It didn’t occur to me to object: I’d been told that this “posture photo” was a routine feature of freshman orientation week. Those whose pins described a too violent or erratic postural curve were required to attend remedial posture classes.

The procedure did seem strange. But I soon learned that it was a long-established custom at most Ivy League and Seven Sisters schools. George Bush, George Pataki, Brandon Tartikoff and Bob Woodward were required to do it at Yale. At Vassar, Meryl Streep; at Mount Holyoke, Wendy Wasserstein; at Wellesley, Hillary Rodham and Diane Sawyer. All of them—whole generations of the cultural elite—were asked to pose. But however much the colleges tried to make this bizarre procedure seem routine, its undeniable strangeness engendered a scurrilous strain of folklore.

THE MISMEASURE OF MAN

There were several salacious stories circulating at Yale back in the 60’s. Most common was the report that someone had broken into a photo lab in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., and stolen the negatives of that year’s Vassar posture nudes, which were supposedly for sale on the Ivy League black market or available to the initiates of Skull and Bones. Little did I know how universal this myth was.

“Ah, yes, the famous rumored stolen Vassar posture pictures,” Nora Ephron (Wellesley ’62) recalled when I spoke with her. “But don’t forget the famous rumored stolen Wellesley posture photos.”

“Wellesley too?”

“Oh, yes,” she said. “It’s one of those urban legends.”

She can laugh about it now, she said, but in retrospect the whole idea that she and all her smart classmates went along with being photographed in this way dismays her. “We were idiots,” she said. “Idiots!”

Sally Quinn (Smith ’63), the Washington writer, expressed alarm when I first reached her. “God, I’m relieved,” she said. “I thought you were going to tell me you found mine. You always thought when you did it that one day they’d come back to haunt you. That 25 years later, when your husband was running for President, they’d show up in Penthouse.”

Another Wellesley alumna, Judith Martin, author of the Miss Manners column, told me she’s “appalled in retrospect” that the college forced this practice on their freshmen. “Why weren’t we more appalled at the time?” she wondered. Nonetheless, she confessed to making a kind of good-natured extortionate use of the posture-photo specter herself.

“I do remember making a reunion speech in which I offered to sell them back to people for large donations. And there were a lot of people who turned pale before they realized it was a joke.”

Distinguishing between joke and reality is often difficult in posture-photo lore. Consider the astonishing rumor Ephron clued me in to, a story she assured me she’d heard from someone very close to the source:

“There was a guy, an adjunct professor of sociology who was working on a grant for the tobacco industry. And what I heard when I was at Wellesley was that, using Harvard posture photos, he had proved conclusively that the more manly you are, the more you smoked. And I believe the criterion for manliness was the obvious one.”

“The obvious one?”

“I assume—what else could it have been?”

In fact, the study was real. I was able to track it down, although the conclusion it reached about Harvard men was somewhat different from what Ephron recalled. But, clearly, the nude-posture-photo practice engendered heated fantasies in both sexes. Perhaps in the otherwise circumspect Ivy League-Seven Sisters world, nude posture photos were the licensed exception to propriety that spawned licentious fantasies. Fantasies that were to lie unremembered, or at least unpublicized until ….

THE RETURN OF THE REPRESSED

It was Naomi Wolf, author of The Beauty Myth, who opened the Pandora’s box of posture-photo controversy. In that book and in a 1992 Op-Ed piece in The Times, Wolf (Yale ’84) bitterly attacked Dick Cavett (Yale ’55) for a joke he’d made at Wolf’s graduation ceremonies. According to Wolf, who’d never had a posture photo taken (the practice was discontinued at Yale in 1968), Cavett took the microphone and told the following anecdote:

“When I was an undergraduate … there were no women [at Yale] . The women went to Vassar. At Vassar they had nude photographs taken of women in gym class to check their posture. One year the photos were stolen and turned up for sale in New Haven’s red-light district.” His punchline: “The photos found no buyers.”

Wolf was horrified. Cavett, she wrote in her book, “transposed us for a moment out of the gentle quadrangle where we had been led to believe we were cherished, and into the tawdry district four blocks away, where stolen photographs of our naked bodies would find no buyers.”

Cavett responded, in a letter to The Times, by dismissing the joke as an innocuous “example of how my Yale years showed up in my long-forgotten nightclub act.”

Wolf’s horrified account attests to the totemic power of the posture-photo legend. But little did she know, little did Cavett know, how potentially sinister the entire phenomenon really was. No one knew until … .

THE NAZI-POSTURE-PHOTO ALLEGATION

This is where things get really strange. Shortly after Cavett’s reply, George Hersey, a respected art history professor at Yale, wrote a letter to The Times that ran under the headline “A Secret Lies Hidden in Vassar and Yale Nude ‘Posture Photos.’ ” Sounding an ominous note, Hersey declared that the photos “had nothing to do with posture … that is only what we were told.”

Hersey went on to say that the pictures were actually made for anthropological research: “The reigning school of the time, presided over by E. A. Hooton of Harvard and W. H. Sheldon”—who directed an institute for physique studies at Columbia University—“held that a person’s body, measured and analyzed, could tell much about intelligence, temperament, moral worth and probable future achievement. The inspiration came from the founder of social Darwinism, Francis Galton, who proposed such a photo archive for the British population.”

And then Hersey evoked the specter of the Third Reich:

“The Nazis compiled similar archives analyzing the photos for racial as well as characterological content (as did Hooton) … . The Nazis often used American high school yearbook photographs for this purpose …. The American investigators planned an archive that could correlate each freshman’s bodily configuration (‘somatotype’) and physiognomy with later life history. That the photos had no value as pornography is a tribute to their resolutely scientific nature.”

A truly breathtaking missive. What Hersey seemed to be saying was that entire generations of America’s ruling class had been unwitting guinea pigs in a vast eugenic experiment run by scientists with a master-race hidden agenda. My classmate Steve Weisman, the Times editor who first called my attention to the letter, pointed out a fascinating corollary: The letter managed in a stroke to confer on some of the most overprivileged people in the world the one status distinction it seemed they’d forever be denied—victim.

My first stop in what would turn out to be a prolonged and eventful quest for the truth about the posture photos was Professor Hersey’s office in New Haven. A thoughtful, civilized scholar, Hersey did not seem prone to sensationalism. But he showed me a draft chapter from his forthcoming book on the esthetics of racism that went even further than the allegations in his letter to The Times. I was struck by one passage in particular:

“From the outset, the purpose of these ‘posture photographs’ was eugenic. The data accumulated, says Hooton, will eventually lead on to proposals to ‘control and limit the production of inferior and useless organisms.’ Some of the latter would be penalized for reproducing … or would be sterilized. But the real solution is to be enforced better breeding—getting those Exeter and Harvard men together with their corresponding Wellesley, Vassar and Radcliffe girls.”

In other words, a kind of eugenic dating service, “Studs” for the cultural elite. But my talk with Hersey left key questions unanswered. What was the precise relationship between theorists like Hooton and Sheldon (the man who actually took tens of thousands of those nude posture photos) and the Ivy League and Seven Sisters schools whose student bodies were photographed? Were the schools complicit or were they simply dupes? And finally: What became of the photographs?

As for the last question, Hersey thought there’d be no trouble locating the photographs. He assumed that “they can probably be found with Sheldon’s research papers” in one of the several academic institutions with which he had been associated. But most of those institutions said that they had burned whatever photos they’d had. Harley P. Holden, curator of Harvard’s archives, said that from the 1880’s to the 1940’s the university had its own posture-photo program in which some 3,500 pictures of its students were taken. Most were destroyed 15 or 20 years ago “for privacy scruples,” Holden said. Nonetheless, quite a few Harvard nudes can be found illustrating Sheldon’s book on body types, the “Atlas of Men.” Radcliffe took posture photos from 1931 to 1961; the curator there said that most of them had been destroyed (although some might be missing) and that none were taken by Sheldon.

Hersey insisted that there was a treasure trove of Sheldon photographs out there to be found. He gave me the phone number of a man in New Mexico named Ellery Lanier, a friend of Sheldon, the posture-photo mastermind. “He might know where they ended up,” Hersey told me.

Going from Hersey to Lanier meant stepping over the threshold from contemporary academic orthodoxy into the more exotic precincts of Sheldon subculture, a loose-knit network of his surviving disciples. A number of them keep the Sheldon legacy alive, hoping for a revival.

Lanier, an articulate, seventyish doctoral student at New Mexico State, told me he’d gotten to know Sheldon at Columbia in the late 1940’s, when the two of them were hanging out with Aldous Huxley and Christopher Isherwood and their crew. (Sheldon had a prophetic mystical side, which revealed itself in Huxleian philosophic treatises on the “Promethean will.” Sheldon was also, Lanier told me, “the world’s leading expert on the history of the American penny.”) At that time, Sheldon was at the apex of his now-forgotten renown. Life magazine ran a cover story in 1951 on Sheldon’s theory of somatotypes.

While the popular conception of Sheldonism has it that he divided human beings into three types—skinny, nervous “ectomorphs”; fat and jolly “endomorphs”; confident, buffed “mesomorphs”—what he actually did was somewhat more complex. He believed that every individual harbored within him different degrees of each of the three character components. By using body measurements and ratios derived from nude photographs, Sheldon believed he could assign every individual a three-digit number representing the three components, components that Sheldon believed were inborn—genetic—and remained unwavering determinants of character regardless of transitory weight change. In other words, physique equals destiny.

It was the pop-psych flavor of the month for a while; Cosmopolitan magazine published quizzes about how to understand your husband on the basis of somatotype. Ecto-, meso- and endomorphic have entered the language, although few scientists these days give credence to Sheldon’s claims. “Half the textbooks in [his] area fail to take [him] seriously,” remarked one academician in a 1992 paper on Sheldon’s legacy. Others, like Hans Eysenck, the British psychologist, have suggested that Sheldon wasn’t really doing science at all, that he was just winging it, that there was “little theoretical foundation for the observed findings.”

Nonetheless, in the late 40’s and early 50’s, Sheldonism seemed mainstream, and Sheldon took advantage of that to approach Ivy League schools. Many, like Harvard, already had a posture-photo tradition. But it was at Wellesley College in the late 1920’s that concern about postural correctness metamorphosed into a cottage industry with pretensions to science. The department of hygiene circulated training films about posture measurement to other women’s colleges, which took up the practice, as did some “progressive” high schools and elementary schools. (By the time Hillary Rodham arrived on the Wellesley campus, women were allowed to have their pictures taken only partly nude. Although Lanier assumes that Sheldon took the Rodham photo, Wellesley archivists believe that Sheldon didn’t take posture photos at their school.)

What Sheldon did was appropriate the ritual. Lanier confirmed that the Ivy League “posture photos” Sheldon used were “part of a facade or cover-up for what we were really doing”—which would make the schools less complicit. But Lanier stoutly defended “what we were really doing” as valid science. As part of his Ph.D. project, he has been examining Sheldonian ecto-, meso- and endomorphic categories and the “time horizon” of the individual.

“Conflicting temporal horizon can account for all the divorce we have today,” Lanier said. “The Woody Allen-Mia Farrow-type thing.”

Huh? Woody and Mia?

“I’m trying to find some clue to the breakup because of the discrepancies between their time focus,” Lanier said.

“Well, Woody’s certainly ectomorphic, but …. “

“No, let me correct you,” Lanier said tartly. “Woody Allen creates an illusion. He puts on a big show of being ectomorphic, but this is all a cover-up because he’s quite mesomorphic.”

“I think he would be surprised to hear that.”

“I know,” Lanier said. “He wouldn’t want to admit it, but the only way you can know this is by looking at photographs very carefully.”

Lanier also filled me in on the cause of Sheldon’s downfall: his never completed, partly burned Atlas of Women. In attempting to compile what would have been the companion volume to his Atlas of Men, which included hundreds of nude Harvard men to illustrate each of the three-digit body types, Sheldon made the strategic mistake of taking his photo show on the road.

What happened was this: In September 1950, Sheldon and his team descended on Seattle, where the University of Washington had agreed to play host to his project. He’d begun taking nude pictures of female freshmen, but something went wrong. One of them told her parents about the practice. The next morning, a battalion of lawyers and university officials stormed Sheldon’s lab, seized every photo of a nude woman, convicted the images of shamefulness and sentenced them to burning. The angry crew then shoveled the incendiary film into an incinerator. A short-lived controversy broke out: Was this a book burning? A witch hunt? Was Professor Sheldon’s nude photography a legitimate scientific investigation into the relationship between physique and temperament, the raw material of serious scholarship? Or just raw material—pornography masquerading as science?

They burned a few thousand photos in Seattle. Thousands more were burned at Harvard, Vassar and Yale in the 60’s and 70’s, when the colleges phased out the posture-photo practice. But thousands more escaped the flames, tens of thousands that Sheldon took at Harvard, Vassar, Yale and elsewhere but sequestered in his own archives. And what became of the archives? Lanier didn’t know, but he said they were out there somewhere. He dug up the phone number of a man who was once the lawyer for Sheldon’s estate, a Mr. Joachim Weissfeld in Providence, R.I. “Maybe he’ll know,” Lanier said.

At this point, the posture-photo quest turned into a kind of high-speed parody of The Aspern Papers. The lawyer in Rhode Island professed ignorance as to the whereabouts or even continued existence of the lost Sheldonian archives, but he did put me in touch with the last living leaf on the Sheldon family tree, a niece by marriage who lived in Warwick, R.I. She, too, said she didn’t know what had become of the Sheldon photos, but she did give me the name of an 84-year-old man living in Columbus, Ohio, who had worked very closely with Sheldon, one Roland D. Elderkin—a man who, in fact, had shot many of the lost photos himself and who promised to reveal their location to me.

THE MYSTERY SOLVED

With Roland D. Elderkin, we’re now this close to the late, great Sheldon himself. “There was nobody closer,” Elderkin declared shortly after I reached him at his rooming house in Columbus. “I was his soul mate.”

Elderkin described himself a bit mournfully as “just an 84-year-old man living alone in a furnished room.” But he once had a brush with greatness, and you can hear it in his recollection of Sheldon and his grand project.

To Elderkin, Sheldon was no mere body-typer: he was a true philosophe, “the first to introduce holistic perspective” to American science, a proto-New Ager. Elderkin became Sheldon’s research associate, his trusty cameraman and a kind of private eye, compiling case histories of Sheldon’s posture nudes to confirm Sheldon’s theories about physique and destiny. He also witnessed Sheldon’s downfall.

The Bonfire of the Nude Coed Photos in Seattle wasn’t Sheldon’s only public burning, Elderkin told me: “He went through a number of furors over women. A similar thing later happened at Pembroke, the women’s college at Brown.” In each case, the fact that female nudes were involved kindled the flame against Sheldon. Toward the end, Sheldon became a kind of pathetic Willy Loman-esque figure as he wandered America far from the elite Ivy halls that had once housed him, seeking a place he could complete the photography for his Atlas of Women.

Rejected and scorned, out of fashion with academic officialdom, Sheldon is still a hero to Roland D. Elderkin. And so when Sheldon died in 1977, “a lonely old man who did nothing his last years but sit in his room and read detective stories,” Elderkin said, “there was nobody else to carry on.” It fell to Elderkin to find a final resting place for the huge archives of Sheldon’s posture nudes.

It wasn’t easy, he said. Elderkin went “up and down the East Coast trying to peddle them” to places like Harvard and Columbia, which once welcomed Sheldon but now wanted nothing to do with nude photos and the controversy trailing them. “That’s how I found out about the burning at Pembroke,” Elderkin recalled. “I was trying to get someone at Brown to accept them, and he said, ‘That filth? We already burned the ones we had.’ ”

“And you know where they are now?” I asked incredulously. “Hersey and Lanier said they didn’t know.”

“Sure I do,” he said. “I was the one that finally found a home for them.”

And then he told me where.

Before we proceed to the location of the treasure itself, it might be wise to pause and ponder the wisdom of opening such a Pandora’s box. With scholars like Hersey alleging eugenic motives behind Sheldon’s project, with the self-images of so many of the cultural elite at stake, would exposure of the hidden hoard be defensible? Is there anyone, aside from lifelong Sheldon disciples, who will step forward to defend Sheldon’s posture photos?

Of course there is: Camille Paglia.

“I’m very interested in somatotypes,” she said. “I constantly use the term in my work. The word ‘ectomorph’ is used repeatedly in Sexual Personae about Spenser’s Apollonian angels. That’s one of the things I’m trying to do: to reconsider these classification schemes, to rescue them from their tainting by Nazi ideology. It’s always been a part of classicism. It’s sort of like we’ve lost the old curiosity about physical characteristics, physical differences. And I maintain it’s bourgeois prudery.

“See, I’m interested in looking at women’s breasts! I’m interested in looking at men’s penises! I maintain that at the present date, Penthouse, Playboy, Hustler, serve the same cultural functions as the posture photos.”

With these words ringing in my ears, I set out to see if I could open up the Sheldon archives.

THE SECRET IS BARED

Down a dimly lit back corridor of the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, far from the dinosaur displays, is a branch of the Smithsonian not well known to the public: the National Anthropological Archives.

Although it contains a rich and strange assortment of archival treasures, it’s particularly notable for the number of Native Americans who travel here to investigate centuries-old anthropological records, poring over them in a cramped, windowless research room whose walls are hung with stylized illustrations of tribal rituals painted by one Chief Blue Eagle. It was here that my quest for another kind of tribal illustration—the taboo images of the blue-blood tribe, the long-lost nude posture photos—culminated at last.

In 1987, the curators of the National Anthropological Archives acquired the remains of Sheldon’s life work, which were gathering dust in “dead storage” in a Goodwill warehouse in Boston. While there were solid archival reasons for making the acquisition, the curators are clearly aware that they harbor some potentially explosive material in their storage rooms. And they did not make it easy for me to gain access.

On my first visit, I was informed by a good-natured but wary supervisor that the restrictive grant of Sheldon’s materials by his estate would permit me to review only the written materials in the Sheldon archives. The actual photographs, he said, were off-limits. To see them, I would have to petition the chief of archivists. Determined to pursue the matter to the bitter end, I began the process of applying for permission.

Meanwhile, I plunged into the written material hoping to find answers to several unresolved mysteries. Although I did not find substantiation in those files for Hersey’s belief that Sheldon was actively engaged in a master-race eugenic project, I did find stunning confirmation of Hersey’s charge that Sheldon held racist views.

In Box 43 I came across a document never referred to in any of the literature on Sheldon I’d seen. It was a faded offprint of a 1924 Sheldon study, “The Intelligence of Mexican Children.” In it are damning assertions presented as scientific truisms that “Negro intelligence” comes to a “standstill at about the 10th year,” Mexican at about age 12. To the author of such sentiments, America’s elite institutions entrusted their student bodies.

Another box held clues to the truth behind Nora Ephron’s tale about smoking and organ size. It turned out to be true that a research arm of the tobacco industry had sponsored studies on the relationship between masculinity and smoking, and that the studies had involved Sheldonian posture photos of Harvard men—although there is no evidence that the criterion of masculinity was the “obvious one” referred to by Ephron. I located a fascinating report on this research in a December 1959 issue of the respected journal Science, a report titled “Masculinity and Smoking.” According to the article, and contrary to the rumor, it is “not strength but weakness of the masculine component” that is “more frequent in the heavier smokers.” Here, perhaps, is the most profound cultural legacy of the Sheldonian posture-photo phenomenon: the blueprint for the sexual iconography of tobacco advertising. If, in fact, heavy smokers looked more like Harvard nerds than Marlboro men, why not use advertising imagery to make Harvard nerds feel like virile cowboys when they smoked?

Finally and most telling, I found a letter nearly four decades old that did something nothing else in the files did. It gave a glimpse, a clue to the feelings of the subjects of Sheldon’s research, particularly the women. I found the letter in a file of correspondence between Sheldon and various phys ed directors at women’s colleges who were providing Sheldon with bodies for the ill-fated Atlas of Women. In this letter, an official at Denison University in Granville, Ohio, was responding to Sheldon’s request to rephotograph the female freshmen he had photographed the year before. Something had apparently gone wrong with the technical side of the earlier shoot. But the official refused to allow Sheldon to reshoot the women, declaring that “to require them to pose for another [nude posture photo] would create insurmountable psychological problems.”

Insurmountable psychological problems. Suddenly the subjects of Sheldon’s photography leaped into the foreground: the shy girl, the fat girl, the religiously conservative, the victim of inappropriate parental attention. Here, perhaps, Naomi Wolf has a point. In a culture that already encourages women to scrutinize their bodies critically, the first thing that happens to these women when they arrive at college is an intrusive, uncomfortable, public examination of their nude bodies.

Three months later, I finally succeeded in gaining permission to study the elusive posture photos. As I sat at my desk in the reading room, under a portrait of Chief Blue Eagle, the long-sought cache materialized. A curator trundled in a library cart from the storage facility. Teetering on top of the cart were stacks of big, gray cardboard boxes. The curator handed me a pair of the white cotton gloves that researchers must use to handle archival material.

The contents of the boxes were described in an accompanying “Finder’s Aid” in this fashion: BOX 90 YALE UNIVERSITY CLASS OF 1971

Negatives. Full length views of nude freshmen men, front, back and rear. Includes weight, height, previous or maximum weight, with age, name, or initials. BOX 95 MOUNT HOLYOKE COLLEGE PHOTOGRAPHS

Negatives. Made in 1950. Full length views of nude women, front, back and rear. Includes height, weight, date and age. Includes some photographs marked S.P.C.

Among the other classes listed in the Finder’s Aid were: the Yale classes of ’50, ’63, ’64, ’66 and ’71; the Princeton class of ’52; Smith ’50 and ’52; Vassar ’42 and ’52; Mount Holyoke ’53; Swarthmore ’51; University of California ’61 and ’67; Hotchkiss ’71; Syracuse ’50; University of Wisconsin ’53; Purdue ’53; University of Pennsylvania ’51, and Brooklyn College ’51 and ’52. There were also undated photos from the Oregon Hospital for the Criminally Insane (which I could not distinguish in any way from the Ivy League photos). All told, there were some 20,000 photographs of men—9,000 from Yale—and 7,000 of women.

In flipping through those thousands of images (which were recently transferred to Smithsonian archives in Suitland, Md.), I found surprising testimony to the “insurmountable psychological problems” that the Denison University official had referred to. It took awhile for the “problems” to become apparent, because, as it turned out, I was not permitted to see positive photographs—only negatives (with no names attached).

A fascinating distinction was being exhibited here, a kind of light-polarity theory of prurience and privacy that absolves the negative image of the naked body of whatever transgressive power it might have in a positive print. There’s an intuitive logic to the theory, although here the Sheldon posture-photo phenomenon exposes how fragile are the distinctions we make between the sanctioned and the forbidden images of the body.

As I thumbed rapidly through box after box to confirm that the entries described in the Finder’s Aid were actually there, I tried to glance at only the faces. It was a decision that paid off, because it was in them that a crucial difference between the men and the women revealed itself. For the most part, the men looked diffident, oblivious. That’s not surprising considering that men of that era were accustomed to undressing for draft physicals and athletic-squad weigh-ins.

But the faces of the women were another story. I was surprised at how many looked deeply unhappy, as if pained at being subjected to this procedure. On the faces of quite a few I saw what looked like grimaces, reflecting pronounced discomfort, perhaps even anger.

I was not much more comfortable myself sitting there in the midst of stacks of boxes of such images. There I was at the end of my quest. I’d tracked down the fabled photographs, but the lessons of the posture-photo ritual were elusive.

“There’s a tremendous lesson here,’ Miss manners declares. “Which is that one should have sympathy and tolerance for respectable women from whose past naked pictures suddenly show up. One should think of the many times where some woman becomes prominent like Marilyn Monroe and suddenly there are nude pictures in her past. Shouldn’t we be a little less condemning of someone in that position?”

A little less condemning of the victims, yes, certainly. (I speak as one myself, although it turned out that my photo was burned in the Yale bonfire of the late 70’s.) But what about the perpetrators? What could have possessed so many elite institutions of higher education to turn their student bodies over to the practitioners of what now seems so dubious a science project?

It’s a question that baffles the current powers that be at Ivy League schools. The response of Gary Fryer, Yale’s spokesman, is representative: “We searched, but there’s nobody around now who was involved with the decision.” Even so, he assures me, nothing like it could happen again; concerns about privacy have heightened, and, as he puts it, “there’s now a Federal law against disclosing anything in a college student’s record to any outsider without written permission.”

In other words, “We won’t get fooled again.” Though he is undoubtedly correct that nothing precisely like the posture-photo folly could happen again, it is hard to deny the possibility, the likelihood, that well-meaning people and institutions will get taken in—are being taken in—by those who peddle scientific conjecture as certainty. Sheldon’s dream of reducing the complexity of human personality and the contingency of human fate to a single number is a recurrent one, as the continuing I.Q. controversy demonstrates. And a reminder that skepticism is still valuable in the face of scientific claims of certainty, particularly in the slippery realms of human behavior.

The rise and fall of “sciences” like Marxist history, Freudian psychology and Keynesian economics suggests that at least some of the beliefs and axioms treated as science today (Rorschach analysis, “rational choice” economics, perhaps) will turn out to have little more validity than nude stick-pin somatotyping.

In the Sheldon rituals, the student test subjects were naked—but it was the emperors of scientific certainty who had no clothes.