Buck Henry takes a bite of chicken hash and leans forward to speak above the restaurant din. “It’s like we’re part of a secret society, or a club of some kind,” he says. “People come out to that house for these parties, and a lot of people are brought who meet her for the first time. And they’re all hesitant and curious, and maybe a little scared. And then they meet her, and, you know … she’s Heidi!”

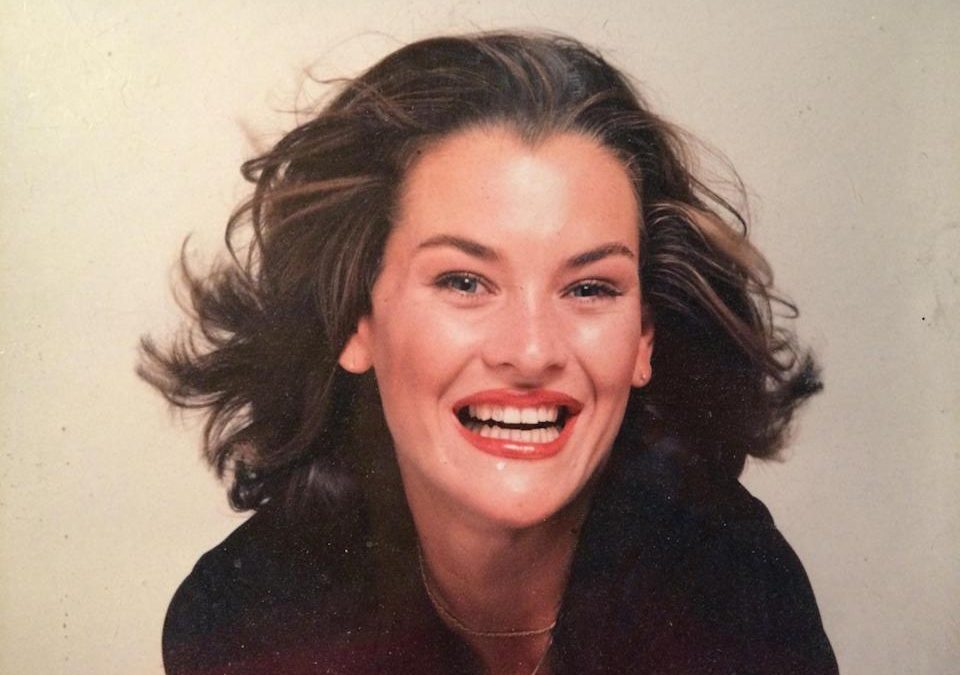

Henry is recounting a gathering held some months ago at the ranch-style home, on 11 acres high above Zuma Beach, that is known to Malibu resi dents as the Old Red House. It is owned by Heidi von Beltz, a stunning and singular 37-year-old woman who was front-page news for several guilt-ridden moments in Hollywood, but who has since settled into a less visible but more complex role. From a distance, she is still a poster adult for Tin seltown recklessness. Up close, she has become some kind of self-performed miracle.

“I don’t want to ascribe to her properties that make her sound like some remote saint,” Henry explains. “But I know I couldn’t do what she has done. And, with all her pain, she in effect seems to be trying to make you feel better. And that is the property of saints. I mean, that’s what they do, right? And this family—well, the von Beltzes have always amazed me. It’s a very complex experiment in human behavior that’s been forced on these folks.”

In 1980, Heidi von Beltz broke her neck in one of the worst on-set accidents in motion-picture history. Working as a double for Farrah Fawcett in The Cannonball Run, the 24-year-old stunt ingenue was a passenger in an Aston Martin without seat belts which smashed into a van during an aborted high-speed driving trick. She was pronounced a quadriplegic, permanently paralyzed from the shoulders down, with a short life expectancy and the grim expectation that it wouldn’t be much of a short life. Doctors told her to accept her fate, learn to love her wheelchair, and understand that any hopes she had—beyond winning a three-ring circus of lawsuits filed on her behalf—were probably false ones. Institutionalization was strongly recommended.

The von Beltz family has been living by its own second opinion ever since. They believe Heidi will walk again, and they greet every day in the kind of anything-for-the-patient emergency mode normally associated with brief recuperations. They have invested so much in Heidi’s not getting accustomed to a wheelchair that she is generally carried from place to place, often by her father. And there are few sights more dramatic than retired actor Brad von Beltz—well into his 60s but tanned and robust, with longish gray hair and a dangling feather earring—picking up his six-foot daughter in his arms and transporting her.

For the first three years after the accident, Heidi and her parents lived in a beach home together, with Heidi’s older brother and sister in close attendance. “At least we didn’t have to worry about empty-nest syndrome anymore,” says Heidi’s mother, Patty, who wears all the family’s emotions, and peppers her conversation with an occasional frazzled “Oh my Gahd!” Then Heidi redeclared her independence and moved out. She now lives alone in the Old Red House, with a rotating staff of seven and her Saint Bernard, Mozart. Her Arabian horse, Excalibor, is stabled in the front yard next to her speedboat. Her parents—“Brad and Mom”—reside half a mile away on Frank Sinatra’s stretch of Malibu beach, in a home purchased as an investment with some of the $7 million in settlements the accident generated. The house has become a popular and lucrative beach “location.” Herb Ritts shoots there often because he loves the light, and Oliver Stone used the house—and Brad for a Leary-esque cameo—in a party scene in The Doors.

On the tony stretch of the Pacific Coast Highway that separates the two homes, the von Beltzes have created Heidi’s World, where time is suspended but life goes on, where the movement of one toe is a more newsworthy event than the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Almost all of Heidi’s friends—from her lifelong best “buddess,” Melanie Griffith, on down—are in show biz. Brad von Beltz was a contract actor at Universal, and until the accident he was also writing and producing (he made the immortal kung fu film Kill the Golden Goose), so he brings an older Hollywood to the party. But the people orbiting the family are there for reasons that are rarely encountered in this company town: purely personal reasons.

“Most of my life is and was a relationship to the business,” says Steve Reuther, producer of Pretty Woman and Sommersby. ”My relationship to the von Beltzes is outside of that. I think that’s part of the remarkable thing about Heidi—she attracts really interesting people in a very meaningful way.”

Actor Ray Liotta, for example, fell in love with Heidi just after her accident. For a crucial year and a half of her recovery, Liotta all but cohabited with the von Beltzes, and he maintains an intriguing, amorphous connection to Heidi. Actress Kathleen Quinlan became a close friend after attending one of Heidi’s grand parties—which became legendary in Malibu, especially in the early years after her injury, when she still had a great need to “perform” in order to show everyone she was going to be O.K.

Bruce Willis, Jamie Lee Curtis, author Jess Steam, and playwright George Furth are just a tiny cross section of the cast of characters who have played roles in the family-produced theater of the obsessed which keeps Heidi cheerled.

The von Beltzes have created Heidi’s World, where the movement of one toe is a more newsworthy event than the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Recently, there has been more to cheer about. After a decade of excruciatingly slow progress, Heidi’s efforts to reteach her body how to do everything have shifted into a new kind of overdrive. One morning in late 1989, as she was being pulled out of bed by her staff, she sat up—by herself. That’s when the Malibu parties were curtailed and the 10-to-12-hours-a-day workouts began in earnest.

The party Buck Henry has been chewing over with his chicken hash was the first in nearly a year. And it was atypical for a von Beltz bash. Heidi still held court in the living room, sipping champagne from a crystal glass held to her lips by a friend and speaking with great animation—without really moving anything but her head, shoulders, and left hand. And every flat surface in the house was still laden with rows of framed, enlarged snapshots of Heidi, her family, and her mostly celebrity pals in various combinations.

But many of the guests spent the majority of the party circulating in and out of Heidi’s bedroom, where the walls were hung with magazine covers of Griffith and Liotta and the VCR had been set up to play a recently shot video. On the tape was the quadriplegic—“or the quad, as they always refer to you in the hospital, which is really charming,” Heidi quips—pedaling away on a motorized bike. As her friends gaped in amazement, the camera cut to Heidi strapped in a “standing frame.” One by one, the straps were loosened until she was standing up by herself—her knees and hips locked by her strength of will. Then she proceeded to bend over from the waist and straighten herself up several times.

“Oh my God,” somebody muttered, “she really is going to walk, isn’t she?”

Before all this happened, Heidi von Beltz was a pair of long legs, a husIky voice, and a fearless spirit who was raised among actors and agents and emboldened by professional skiers and stuntmen. The first woman ever to perform a backflip on skis, she gave private lessons as a teen and later settled into an ambitiously haphazard career of modeling and acting, including small roles in movies and on such TV shows as Charlie’s Angels, Starsky and Hutch, and a Bob Hope special.

“I met Heidi when I was 15 and she was 16,” recalls Melanie Griffith. “I was in awe of her. She was the most beautiful, incredible woman. She was always a daredevil, and I was timid; she had to push me off the ledge. She was wild and always very naturally athletic, She was also very secretive; she was always doing something that nobody knew anything about. She wasn’t a braggart about the stuff she could do. She’s amazing—the best friend I ever had. We even lived together one year in Malibu after Don [Johnson] and I broke up.”

Buck Henry has graphic memories of the dynamic duo. “Melanie and Heidi together was, like, everyone’s dream,” he says. “You couldn’t have a more poignant fantasy than the idea of being shipwrecked on an island where only you, Melanie, and Heidi survived. Because you know they could build the house, too, and kill the animals. They were both, as young girls, whatever the California equivalent is of street-smart.”

Heidi’s friendships with stunt pros— she and Griffith were dating veterans Bobby Bass and Buddy Joe Hooker, respectively—led her through the side door into the film business, beginning with Smokey and the Bandit II, which starred Burt Reynolds. The film was directed by former stuntman Hal Needham, who early in his career had done stunts for Brad von Beltz on the TV series Have Gun, Will Travel.

“Heidi was, like, one of the celebrities of that time, when the stunt mystique was just really strong,” says her friend Keefe Millard, an actress married to stunt coordinator Dean Ferrandini. “The late 70s was just a real big time for stunts. There were lots of big action films, and they’d have live stunt competitions. And Heidi was a starlet of that whole scene.”

“Heidi was like an ad for big, perfect American kids,” Buck Henry adds. “Actually, she still is. It’s the same face, the same animation; when it lights up, it’s still spectacular. Laid out on her hospital stretcher between therapy sessions, she was still a dream date.”

“Heidi is just a great adventurer,” says Kathleen Quinlan. “It’s hard to find women friends who want to go out and do things. She’s fearless, and this girl is macho beyond belief. We used to go water-skiing on her speedboat—she loves to go fast. We’d tow her out in a rubber boat from the beach.

“Sometimes we call Heidi ‘the Queen of Malibu.’ She’s royalty. She’s more glamorous than I’ll ever be. I remember the first thing she learned how to do when her arm started coming back was to hold a cigarette and smoke it. And she loves to travel in that Hollywood world; she knows more people in the industry than I do. We got a limo and went to Melanie’s opening of Working Girl together. We had a blast!

“She never lets you know how much pain she was—or is—in. She doesn’t like to give it that much attention. One day they’re going to do a movie of her story. She said she wanted me to play her, and I told her I didn’t know if I could, because I would have to go into such a dark place. It would be, metaphysically, really painful, especially because she’s my friend.

“In the last few years, I haven’t been able to see her as much. I really miss her, but it’s like she’s in a master’s program at a university. She has it all mapped out, and by the time she’s done with what she has to do each day, she’s ready for bed. It’s like she’s training for the Olympics.”

It is early afternoon in Malibu, and Heidi is finishing her ninth mile on a contraption called a hand bike. Sunlight reflects off the ocean and fills her small workout room through a floor-to-ceiling window. Heidi’s blond hair is tied back, her forehead is jammed into the bike’s padded headrest, and her bright-blue eyes are clenched shut. She chews red Trident about as hard as gum can be chewed. With sweat pouring over her Teutonic face, she looks like a Brueghel painting of an aerobics instructor.

Standing above her in the room is trainer Gayle Olinekova, a former worldclass runner and author of the best-selling fitness book Go for It!, who now does private coaching. Olinekova helped Heidi design the program she has been on for the past two and a half years. Before the trainer arrives, Heidi does the approximately three hours of stretching she goes through each morning, beginning with her toes and feet and working her way up to her arms and shoulders and finally her hands—which curled tightly in on themselves a year after the accident and are slowly being coaxed open like time-lapse roses. The stretching prepares her for the grueling workout: a combination of traditional exercise and “patterning”—manually working the nonfunctioning muscles until they get the hint. The hand bike is actual exercise. Olinekova wants Heidi to try to finish one more mile; when she reaches the homestretch, the trainer barks, “C’mon— Jaws, Jaws, get back to that boat!”

At 10 miles, Heidi stops, raises her dripping head, and asks Emma, one of the seven Latino women who work for her in shifts around the clock, to readjust her trunk and legs in the chair. Heidi’s condition has made her Hollywood’s ultimate actor turned director. She must tell someone precisely when and how to do almost everything for her. After her body parts are readjusted, she calls for a reapplication of her one cosmetic affectation: frosted pink lip gloss, applied with a wand that she nearly bites down on.

Before Heidi begins the next exercise, she asks about something she feels in her left shoulder—the last place where she is actually injured. For a decade, she didn’t know what was wrong with it; then, for two years, she believed there was an undiagnosed dislocation. To explain the sensation in her shoulder, Olinekova uses the anatomy book that Heidi keeps on a music stand in her workout room. When Heidi is trying to get her body to do something, she stares at the book and studies the machinery of the human body, trying to figure out a way to “play” herself.

“Anytime Heidi moves,” the trainer explains, “she rehearses it in her mind.” Then she just does it, or keeps trying until she can, which may take minutes, hours, days, or even years. “Over the years, I’ve had people with spinal-cord injuries call who want to know what I do,” Heidi says. “I tell them, and they say, ‘Jeez, that sounds like a lot of work.’ I know that, but what am I supposed to do, sit here and get bedsores—which, by the way, I’ve never had, just like all the other stuff the doctors said would absolutely happen and didn’t. Oh, don’t get me started…”

“I met Heidi when I was 15 and she was 16,” recalls Melanie Griffith. “I was in awe of her. She was the most beautiful, incredible woman.”

After the accident, Heidi was totally limp and without feeling or control from the shoulders down. “I was just this head,” she recalls, “like ‘the brain that wouldn’t die.’” Besides the badly broken neck—she was found with the back of her head resting between her shoulder blades, but the spinal cord wasn’t severed—she had a broken hip and leg. A bone fragment in her phrenic nerve severely restricted breathing and speech; for a while she communicated by clicking her tongue. Stomach problems left her practically unable to eat. The head trauma caused sounds to be maddeningly amplified; that and the constant pain kept her from sleeping more than a few minutes at a time.

Brad helped set Heidi’s attitudinal agenda as soon as she came to in the hospital, putting into action the spiritual combo platter of self-reliance and old fashioned “religious science” he refers to repeatedly as “metaphysics.” (Brad and Patty were involved with Christian Science well before the accident, but more for its “mind over matter” ethos and practitioner counseling: “We’re not joiners,” Brad says.)

“In the hospital, Brad wouldn’t let anybody tell me what had happened,” Heidi recalls. “When I finally asked him, he said, ‘You were in an accident and fucked yourself up pretty good, and you gotta get well.’ I figured, Hell, I can do that, and that’s pretty much the way we’ve always approached it, like a sports injury you work back from. When he and Mom said everything would be O.K., all my fear and anxiety left, and I never really had it back again, no matter what doctors have said during the course of this whole thing. We just take care of business—that’s what Brad always says.”

The von Beltzes were without much encouragement from the medical-industrial complex, which has only very recently begun to treat each of the 12,000 spinal-cord injuries a year as unique, rather than writing them off en masse. The new gospel is that “paralysis” may often be an inexact diagnosis of a temporary condition, made permanent only when patients are too dispirited or gullible to ask more questions. Places such as the Miami Project to Cure Paralysis are trying to reorient public perceptions and physicians’ biases. But medical proselytizing goes very slowly.

“The bottom line is, the minute the neck is broken, they come right in and say, ‘Forget it, it’s all over,’” Patty von Beltz scoffs. “The doctors’ favorite thing is, they don’t want to give you false hope. Hey, any hope is better than nothing. And then the insurance companies do nothing but hassle you. They didn’t want to pay for things. It was expensive. Brad was a trust-fund baby, thank Gahd. All they want is to declare your condition ‘permanent and stable’ so they can pay off a lump sum and close the case. They’re so stupid!”

Heidi has tried a lot of things since 1980—hypnosis, acupuncture, biofeedback, electrical stimulation, pain management, aura management, psychics, even a televangelist’s cattle-call healing. The only near constant in her rehabilitation, besides physical therapy, has been an aggressive, often painful chiropractic deep-muscle manipulation called the Griner Method, which supposedly drives lactic acid from muscles “in spasm” and “encourages neural transmission” to affected areas. In a normal week, Gayle Olinekova comes to the Old Red House on Mondays and Thursdays; after morning workouts on Tuesdays and Fridays, Heidi is driven to the Santa Monica office of chiropractor Eliot Griner, the estranged son of her former chiropractor, who invented the Griner Method.

On weekends, Heidi works out with her staff. When she travels—as she did a lot last year, spending two weeks in Aspen with Melanie Griffith and several stretches in Carmel with her brother’s kids—she takes much of her equipment with her and does the same thing. Wednesday is her day off: she often goes to the movies with her mother.

More than 12 years after being told she’d be dead in 5, Heidi has nearly complete feeling from the waist up; she describes the feeling in her legs at its worst as the kind of numb burning she once associated with the onset of frostbite, “when you’re touching ice and it begins to feel hot instead of cold.” Her breathing and hearing are just about normal, and Lord knows she can talk. When she clicks her tongue now, it’s usually because she and her mother, a couple of eye rollers, are gossiping about Hollywood, skewering doctors, or yakking about current events.

Heidi can move—sometimes very slowly, but at least voluntarily—nearly every muscle in her body. Her left arm is, so far, her most useful appendage. She can sit up “like a normal person” and comfortably hold herself in that position for as long as she likes. Because she has been working to counter the effects of her shoulder problem— for which she plans to get surgery this year—the stabbing pain she had between her shoulder blades for 10 years is gone. She sleeps through the night, and while her appetite is still not great, she does eat at least a meal a day, usually healthful stuff, but she occasionally gives in to her craving for French fries by driving with Brad down to the Malibu McDonald’s.

“Heidi was like an ad for big perfect American kids,” says Buck Henry. “Laid out on her hospital stretcher, she was still a dream date.”

Heidi endured years of diapered inconvenience because she refused to be permanently catheterized; during her trial, her lawyer made much of the fact that she was incontinent while acting as maid of honor at Melanie Griffith’s 1982 wedding to actor Steven Bauer and during an ill-advised appearance on Donahue. But now she can basically control her elimination processes, although she still must be carried to and from the bathroom. Her period, which doctors assured her she would never have again, was actually one of the first things that returned.

And while Heidi doesn’t have complete feeling below the waist, she can have, and enjoy, sex. She is a worldclass flirt, but she says sex and romance are not big issues in her life. Or perhaps they are the biggest issues, because they have been placed in emotional escrow, put on hold in a way very little else in her active life has been. She is never reticent, though, about expounding upon whom she sees in that light at the end of the tunnel. Eleven years after her breakup with Ray Liotta, a framed picture of the couple sits encircled with shells on the grand piano in her parents’ living room.

Liotta left his New York soap-opera career in 1981 to pursue film work, swapping apartments with Melanie Griffith, who was dating his college classmate Steven Bauer. “The first night I was in California,” Liotta recalls, “I was far away from home, and I just sat there and I looked at the list of phone numbers Melanie had on her cupboard, and I saw the name Heidi.” Melanie had told Ray about her best friend, and he recalled a photo of her, taken at a party the von Beltzes threw on a yacht: Heidi, just out of the hospital and unable to sit up, had been lashed in her wheelchair to the boat’s mast.

She turned him down on his first call, because she was still living with 46-year-old Bobby Bass, the stunt coordinator on The Cannonball Run, to whom she had gotten engaged only weeks before the accident. Finally, she let Liotta come over. “I went up there,” he says, “and here’s this absolutely beautiful … incredible girl who just happened to be paralyzed from the neck down. We talked for about eight or nine hours.” Bass soon moved out in a huff, and Liotta joined the family.

“Ray gave me back my life,” says Heidi. “He really made me feel female again, and I hold him responsible for it all, because that was the most crucial year. I had no energy at all, I had no endurance, and Ray pushed me. He took me to my first movie down in Malibu. That was my first time out away from my family in almost a year. I was so scared. But Ray would never want anyone around us. He always wanted to take care of me himself … It was a mad, passionate love affair. We wanted to get married so bad. And nobody is gonna tell me I couldn’t feel what we did. We had a wonderful, sexual love life—internally I could feel everything.

“We spent a full year, 24 hours a day, partying. Martinis were my big thing then. Pot helped a lot; it was the only thing that really relaxed my body without getting me doped up. I had stopped taking any painkillers or that stuff after the hospital.”

During their time together, the story of their romance was optioned for a film by Orion, and they tried to push each other in their careers. But for Heidi a return to work was far more premature than she could comprehend. And Liotta was barely paying attention to his acting. ‘‘We were so consumed with each other we were disregarding our personal goals,” she recalls. ‘‘He was neglecting his career, and I wasn’t working on getting up. So we broke up. Letting him go was the hardest thing I ever had to do in my life.

‘‘Shortly after he left, I went to the beach and vowed that I would be walking to get back together with Ray. Being with him has always been my main goal, my main focus. He and I are apart, and we don’t even talk that often, but we’re together. We have an unspoken communication … although every once in a while I’ll leave a message on his machine like ‘Roses are red, / Violets are blue, / Your ass is mine, / And don’t you forget it.’ … I don’t feel I’m missing out on anything. We both have work to do now.”

Liotta is more close-lipped about all this. When I profiled him a year and a half ago, Heidi was the first thing he brought up—even before plugging his new film. But he spoke of her in the past tense and said nothing that would justify a recent tabloid headline: HUNK RAY LIOTTA: I LOST MY HEART TO PARALYZED STUNTWOMAN HEIDI.

“Melanie and Don are my role models for people who can have a gap and get back together,” says Heidi. “They were apart for 16 years! Ray and I still have five years to accumulate. I don’t see any problem here.”

Since Liotta left, there have been no more romances, but several important men have come into Heidi’s life. One was Bruce Willis, who brought his infectious charm to the Heidi party for two years before getting involved with Demi Moore. Another was Steve Reuther, who moved in down the beach from the von Beltzes when he left the William Morris Agency to start a producing career. Unknown to most of his colleagues, Reuther had been a quadriplegic himself because of an auto accident in his early 20s, and had rehabilitated himself after several years of paralysis.

“Heidi and I connected on a very deep level,” he recalls. “I tried to be an influence in her life that only dealt with recovery. The incidentals of the boyfriend or the career or the lawsuit, the parties, the notoriety … I didn’t give a shit about any of that stuff, and I encouraged Heidi not to focus on them. There was such a whirlwind around her, so many people in her life. I was trying to get her to focus on the work she needed to do.

“I was frustrated with her when I felt she wasn’t paying enough attention to her recovery. But part of my role was that I represented something to her and the family—I had come back from a similar situation. In 1983, 1984, I saw her every day, and the family really took me in. For me, the most meaningful times were the quietest ones, when I would work with Heidi’s hands, which had just begun to curl in.”

Jess Steam, who initially met the von Beltzes because Brad was a fan of his books on metaphysics, has taken Heidi under his tutelage. “I’ve heard many people say what an inspiration her whole life is, and the way she’s approached it,” he says. “Her situation obviously makes you consider how infinitesimal your own problems really are, but I have never left her company feeling sorry for her. I think that Heidi, living so much within herself at times, is ideally suited to do a great book.”

Ray Liotta recalled a photo of her at a party the von Beltzes threw on a yacht: Heidi, lashed in her wheelchair to the boat’s mast.

The lawsuits surrounding the Cannonball Run crash could be a book on their own, although not a very life-affirming one. “It’s a disgrace to the legal profession, what happened to this woman,” says the attorney who eventually tried the case. “The lawyers were jockeying to get fees rather than fighting for the client.” In 1980, amid massive press coverage of the accident, the von Beltzes retained San Francisco-based Melvin Belli, the aging King of Torts, to represent them. When the filing deadlines neared and little seemed to be happening, the disillusioned family consulted with R. Browne Greene, a prominent L.A. trial lawyer.

Greene’s firm thought it had taken the case, and prepared a $10 million suit against everyone connected to the accident, including the film’s director and star, Hal Needham and Burt Reynolds. Two weeks later, Belli announced that he represented Heidi again, and was filing a $71 million suit on her behalf. Legal journals noted with amusement that paperwork in Belli’s suits appeared to have been photocopied from Greene’s, and wondered about clients’ choosing negligence lawyers according to who could ask for the most.

The von Beltz lawsuits occupy eight massive volumes in the otherworldly subbasement of Los Angeles County Superior Court. They explain how the car in question was supposedly declared undrivable and was sent away for repairs and seat belts a day before the accident; it returned slightly more drivable, albeit with bald tires, bad steering, and, still, no seat belts. In the pleadings, Hal Needham is painted as a director who callously disregarded the condition of the car because he was in a hurry to finish the stunt by the end of the day. In the first turn of the second take, the front end of the car went “to mush”—which is why driver Jimmy Nickerson didn’t ditch out to the right, as had been pre-arranged, but veered left into the van. Heidi recalled that the last thing she heard was Needham’s voice over the walkie-talkie yelling, “Faster, faster.”

As the suits got filed and amended, the competitive lawyering grew more ludicrous, and the bad blood between Greene and Belli boiled. Belli worked overtime to ensure that Greene lost a 1981 election for the presidency of the California Trial Lawyers Association. He then took on a $7 million malpractice suit against Greene on behalf of former Greene clients who had lost a case against the Ford Motor Company and then claimed they hadn’t been told the amount of the settlement offer—$2 million—from the automaker. (Greene subsequently won the suit.) The acrimony was blamed on Belli’s anger over Heidi’s case—ironic, since Belli was associated with the proceedings in name and fee percentage only. The case had been picked up by David Sabih, an ambitious young lawyer in the Belli firm.

In the summer of 1982, the stunt fatalities on the set of The Twilight Zone increased public interest in Hollywood safety and elevated Heidi’s case to “harbinger” status. Six months later, Sabih and the von Beltzes’ workmen’s compensation specialist, Robert Buch, were reaching a $1.13 million settlement with the insurer. Greene filed a lien against the settlement fees for his work in filing the original suit. Sabih then sued Greene for $15 million for intentional infliction of emotional distress on Heidi. (The suit was subsequently dismissed.) Then Buch sued Belli, claiming he hadn’t received all of his promised share of the fees for the workmen’s comp settlement. Belli finally announced that he was waiving his fee for Heidi’s settlement, a magnanimous public gesture that also ensured there would be no fees to put a lien on.

In January 1983, all the defendants but Hal Needham and his insurers were dropped. It was two years before they reportedly offered a settlement of $15,000 a month, tax-free, for the rest of Heidi’s life; it was rejected. A year after that, Heidi accepted a $5.8 million out-of-court settlement from Needham’s carriers. But she took him to court anyway, seeking the “excess insurance” in his policies and a chance to bring the negligence issues to public attention.

The trials were an interesting test of wills between lawyer and client. Sabih wanted Heidi to appear as pitiable as possible, and encouraged her parents to describe the horrors—even those long past—of her ordeal, especially how upset she became when her friends had children. But Heidi refused to “play cripple,” even though she knew it might cost her money. The first trial ended with a deadlocked jury. Eight jurors had sided with Heidi on all counts, but the dissenters were adamant. Two of them actually told Sabih that Heidi ‘‘deserved to be in this condition,” since at the time of the accident ‘‘she was living in sin” with her boyfriend. They began again with another jury. This time, the jury found Needham negligent and awarded Heidi $7 million. But she was also found 35 percent negligent for doing the stunt without a seat belt, so the award was reduced to $4.5 million. Because they were suing for excess insurance, they could recover only on an award higher than the $5.8 million Needham’s insurers had already paid. Heidi ended up with a moral victory, but Needham’s insurers didn’t have to pay her another dime, saving even the $750,000 they had been dangling during the two trials to settle before the verdict.

I meet so many people who feel so sorry for me.” She shakes her head. “I feel sorry for them. They don’t know who they are.”

The von Beltz case did, however, make a lasting impact on Hollywood. It helped cause the film industry’s labormanagement safety committee to require seat belts on all stunt cars and forced the Directors Guild to change its stunt policies: directors can no longer alter stunts on location, as Needham did. And the arcane legal argument used to convince a jury that Needham was Heidi’s boss and not a fellow employee of the producer’s (Californians can’t sue fellow employees for on-the-job accidents) shook a favorite Hollywood tax dodge, billing personal services through a “loan-out company.” Upheld on appeal, the “loan-out” reinterpretation changed California law.

“It would have been nice to have that last million they were offering,” says Patty von Beltz with a sigh, “but Heidi wanted to go for broke. After the attorneys’ fees and everything, she was left with a little more than $3 million. Even invested at 10 percent, with all the people she has working for her, it’s not a lot. We budget, we work it out. We invested in the house—with location fees, it’s actually paying for itself right now. It will have to go at some point. And that will be enough money to take care of her until she’s up, or dead, or whatever … Did I say that? Oh my Gahd.”

The new Nicky Blair’s is still old Hollywood. Blair himself—an actor in films from the ’50s through the ’70s—works the main room relentlessly. Being out in the wheelchair at a restaurant where she’s recognized— and where everyone will try too hard— reminds Heidi of all the people who just don’t get what she’s trying to do. ‘‘People still walk on eggshells; they don’t want to say anything wrong,” she says. “They don’t know how much to talk about your condition; they’re so set in their thinking. That’s the most entertaining thing of all. They talk to you, and then they’re crying behind you, ‘This poor little girl, she’s so deluded. She’s never gonna get up. How cruel they are to let her think that will happen.’

“I don’t mean to be critical. I’ve actually grown to love people through all of this. I’ve been really impressed with the quality of kindness. Sometimes Mom and I go somewhere without Brad, and we need someone to help carry me from the car. We just get some guy walking by and say, ‘Hey, could you grab her legs for a second?’ And they always do it. Yeah, I’ve really been pleasantly surprised by people.”

During dinner, actor Danny Aiello, who knows Heidi only from others’ reports, approaches the table to pay his respects. He lowers himself on bent knee to Heidi’s wheelchair. “Oh, you’re so gorgeous,” he starts, an actor without lines. “Burt told me so much about you. And I just want to tell you how amazing I think you are. You’re gorgeous.” He turns to the other diners, demanding, “Isn’t she gorgeous?”

As he rises reverently and takes his leave, the Queen of Malibu grins archly to her tablemates and rolls her blue eyes.

“The one thing I like about this injury,” she says when he is well out of earshot, “is that you always know who you are and what you’re supposed to be doing. I meet so many people who feel so sorry for me.” She shakes her head. “I feel sorry for them. They don’t know who they are.”

TK