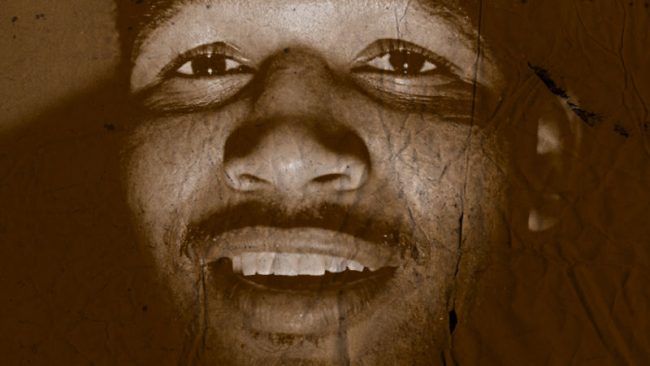

The great ones never lose their style. Even today Joe DiMaggio swings the bat majestically in the Old Timers games. Sammy Baugh can show a rookie quarterback how to lead a receiver slanting across the middle. Put Eddie Arcaro up on a three-year-old in the backstretch and the horseplayers would know him without binoculars. It’s this way with Sugar Ray Robinson. Except that he’s not retired. He’s wearing white trunks and his black boxing shoes scratch across the resin-covered canvas. He could be fighting anybody anyplace, but this night last summer in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, he’s in with somebody named Clarence Riley in a dumpy little outdoor arena named Wahconah Park.

Suddenly Sugar Ray throws two quick left hooks and the small crowd comes alive. The left hooks always were part of his style. They remember seeing him throw left hooks like that on television when he was the biggest name in boxing.

It’s like this wherever he goes. He throws the left hook and, in their minds, the spectators see him swinging at Carmen Basilio. Or he moves those slender shimmering legs and thumps a right hand into the midsection and they see Jake LaMotta doubled-up against the ropes. But now Sugar Ray is 44 according to the book, 43 according to him. Now the style lasts only a few seconds. It used to last 15 rounds when it had to. That was when many boxing people considered him the best fighter of all time. “Pound for pound, the greatest”—that phrase was almost part of his name.

But the real boxing people haven’t seen Robinson lately. It’s just as well. He’s a sideshow freak now. Step right up, an invisible carnival barker seems to be shouting whenever he fights. Step right up and see the great Sugar Ray Robinson. But the great Sugar Ray Robinson isn’t great anymore. His skill is shot. So is his bank account. One way or another he has gone through almost $3 million in purses. “I’m not desperate,” he claims, “but I don’t have the money like I used to.”

It has to be more than the need for money, though, that sends him back into the ring for peanut purses against unknowns like Clarence Riley. It’s ego and the love of applause and the need for adulation as well. But mostly ego. It’s a big thing with him.

It always was. One night in 1950 Sugar Ray pranced out to listen to the referee’s instructions before a 10-rounder with a tough middleweight named George (Sugar) Costner. Earlier in the week Costner had been popping off about how—when he won—he would be the Sugar. Now, as Robinson stood in the ring, wearing a blue satin robe and his face hooded in a towel, he peered at Costner. When the referee was finished, he said, “Listen, Costner, there’s only one Sugar. And that’s me. So let’s touch the gloves now because this is your last round.”

Sugar Ray caught him with a left hook and a straight right hand and Costner was on his back. KO 1, it reads in the book.

“I couldn’t have beaten Robinson on the best night I ever saw.”

Sugar Ray held the middleweight title five times. Earlier he held the welterweight title. But as early as three years before he was a champion, Henry Armstrong made it clear how good Sugar Ray was. They didn’t come much better than Henry Armstrong. He’s the only one ever to hold three titles simultaneously—welterweight, lightweight and featherweight. At Madison Square Garden one night in 1943, near the end of his career, Armstrong went 10 rounds with Sugar Ray. Everybody had Sugar Ray winning almost every round. He jabbed. He hooked. He threw the right hand into the midsection. But every time Armstrong started to sag, Sugar Ray would clinch and hold him up. Out of respect, he refused to knock him out. Later Armstrong was sitting on a rubbing table and somebody tried to console him.

“It’s too bad,” the man said, “that you never had a chance to fight Robinson when you were at your peak.”

Armstrong smiled and shook his head. “I couldn’t have beaten Robinson on the best night I ever saw.”

Sugar Ray almost won the light-heavyweight title, too. He was way ahead of Joey Maxim on points in 1952 at Yankee Stadium. But it was a brutally hot, humid night. When it’s like that in New York City it’s cooler in a sauna. The temperature was announced as 104 at ringside, and in the ring, under the glare of the arclights, it was around 120. Between rounds Sugar Ray slumped on his stool and George Gainford sponged his head and Harry Wiley held the front of his trunks away from his stomach so he could breathe easy. When Sugar Ray went out for the 14th round, he threw a right hand. It missed Maxim and Sugar Ray fell flat on his face. Heat exhaustion, the doctors called it after he had been counted out. [Editor’s note: Robinson’s fall came in the 13th round. He wasn’t counted out. He lost when he didn’t answer the bell at the start of the 14th.]

Technically, he had been knocked out—for the only time in his career. But Joey Maxim still hasn’t touched him.

Sugar Ray retired a few months after the Maxim fight. Two years later he made a comeback—some say the most remarkable comeback in sports history. He would win the middleweight title three times in a series of battles with Bobo Olson, Gene Fullmer and Carmen Basilio. One day in 1959, when Ingemar Johansson was the heavyweight champion, matchmaker Teddy Brenner was having coffee with Harry Markson, his boss at Madison Square Garden.

“I wonder,” Brenner said, “what Robinson would draw with Johansson?”

“Never,” Markson said. “The public wouldn’t take the match seriously.”

“I take Robinson seriously,” Brenner said, “no matter who he’s fighting.”

That one never came off, of course, but only because of the 40-pound difference in weights, not because Teddy Brenner was exaggerating Sugar Ray’s ability. “He always had everything a great fighter should have—in abundance,” Markson says.

Markson always negotiated the money when Sugar Ray came into the Garden to talk about a match. Ray would drive down from Harlem in his big fuchsia convertible—in recent years it was a Lincoln, before that a Cadillac. He’d park it next to the “No Parking” sign under the Garden marquee on Eighth Avenue.

“C’mon, Sugar,” the cop would say to him. “If the sarge comes by, I got to give you a ticket.”

“Now, ol’ buddy,” Robinson would say, “you wouldn’t give ol’ Sugar a ticket, would you, ol’ buddy?”

They never would, either, because the fuchsia convertible was part of his style, too. He used to take it to Europe with him. In 1951, when he sailed on the Liberté to Le Havre for a two-month tour, the fuchsia convertible was aboard and so was his entourage of 17 people: his manager, his trainer, a few cornermen, his wife, some relatives, some friends, his barber, his cook, his chauffeur, his golf pro, his masseur and his valet. That was the tour that ended with him losing the middleweight title to Randy Turpin in London.

“Turpin beat him,” said Lew Burston, who knew all the European fighters, “because Robinson had Paris in his legs.”

In Paris there was a crowd waiting for him every morning outside the Claridge Hotel. Broads, mostly. “Temptations,” Robinson once said, “nobody knows what temptations there are for a fighter.” When he would emerge onto the Champs Élysées, the crowd would shout, “Rah-bean-soan … Rah-bean-soan,” and the people would swirl around him and he would sign scraps of paper and their autograph books.

This afternoon last summer in Pittsfield the sidewalk was empty outside Unit 3 of the Tanglewood Motel.

Sugar Ray had come up in the morning from New York City in a gray station wagon. In the back seat was a beat-up brown suitcase with a beat-up French Line sticker on it. There were three people with him, his chief adviser and two cornermen. George Gainford, who taught him the moves almost 30 years ago, was in the back seat with John Seymour, Tommy Brockett was behind the wheel and Sugar Ray slid into the front seat. It was shortly before two in the afternoon and they were about to leave the motel for the weigh-in when the proprietor walked over.

“Anything you fellows need?” he asked, leaning at the window. “Your room okay?”

“Fine,” Robinson said, “but how do we get to … to where the fight’s going to be?”

This never used to be a problem. Madison Square Garden, Chicago Stadium, Palais des Sports in Paris, everybody knows how to get there. But Wahconah Park in Pittsfield, Massachusetts?

“Go through town,” the motel man said, “and make a left at the hospital. Go a little ways and you’ll see a dirt road, an alley like, on your left leading to it. Can’t miss it.”

The station wagon swung out onto Route 7. Soon it was gliding through Pittsfield. Sugar Ray glanced through his sunglasses at the white colonial homes shaded by tall trees.

“Nice town,” he said. “Wonder how big?”

“About 60,000,” somebody said.

More people than that—61,370—saw him the night in 1951 that he won back the middleweight title from Randy Turpin at the now-leveled Polo Grounds in New York. Robinson was ahead on points in the 10th round when they banged heads and the blood spurted from a cut above his left eye. It matted the eyebrow and streaked down his face and he was blinking to keep the blood out of his eye.

“I had to do something,” Sugar Ray would say later in the dressing room. “I was afraid they’d stop it.”

Robinson didn’t say anything. Maybe he was thinking he had never appeared in such a dilapidated arena.

They stopped it, all right. Robinson threw an uppercut and Turpin went sprawling. When Turpin got up, Robinson clubbed him with both hands. The next day, looking at the movies, somebody counted 31 punches in 25 seconds. Turpin lurched back against the ropes. His arms were down and he was helpless. KO 10, it reads in the book. The gate for that one is in the book, too: $767,626 a record for a non-heavyweight fight. At Wahconah Park in Pittsfield he might draw a couple thousand dollars.

“There’s the ball park,” somebody in the station wagon was saying now. “On the left. Behind those stores.”

The station wagon bounced across the ruts in the dirt road leading to an old wooden stadium surrounded by an eight-foot wire fence and a dusty dirt parking lot. It was built when Pittsfield had a Class C ball club in the Canadian-American League. But the league folded after the 1951 season. The ball park is seldom used.

Robinson didn’t say anything. Maybe he was thinking he had never appeared in such a dilapidated arena. Or maybe he was thinking of the people who had gathered to greet him. “I love to have people around,” he often says. “People make me go.” There were about 30 people outside the ball park. There were some kids, but there were middle-aged men, too. Some of them were wearing sport shirts and looked as if they were on vacation. Others wore khaki work clothes and thick-soled work shoes and looked as if they were going to be late getting back from their lunch hour. None of them had Sugar Ray’s way with clothes. Few people do. This day he was wearing a nubby beige sport shirt, cuffless lime slacks, brown socks, and brown loafers.

They don’t see lime slacks too often in Pittsfield. Maybe there’s a dude at the country club who wears them playing golf. But nobody wears them punching the time clock at the General Electric plant, or milking cows on the farms outside this old New England town in the Berkshire Mountains.

When Sugar Ray got out of the station wagon, everybody seemed to notice the lime slacks first. Then they noticed him. He had on sunglasses, but his face looked the way everybody remembers it. Unmarked. Straight nose. Slick hair. Thin moustache. There is a fuzz about the size of a nickel below his lower lip now, but his body is still lean and lithe. And he still has the strong, solid neck. All the great ones, in every sport, have this kind of neck.

“Hey, Sugar,” a stranger said, “good to see you here.”

“Hi, ol’ buddy,” Robinson said. “It’s good to be here.”

It was good, too, for promoter Sam Silverman. He had been sweating out Sugar Ray’s arrival. Promoters always do. For one reason or another, Sugar Ray has forced the postponement or cancellation of about 30 fights. In Boston one night three hours before a fight he told Silverman, “I’m not going in,” and he didn’t. Two weeks earlier Silverman had him scheduled to fight in Pittsfield, but he had begged off. Silverman rescheduled him but the promoter wasn’t convinced he’d show. He didn’t order any posters.

“I’m afraid to jinx myself with Ray,” Sam says. “Every time I order posters when he’s fighting, something happens.”

Now, standing outside the shabby ball park, Silverman greeted him. “They got some of the prelim kids weighing in now,” Sam said, “but I’ll get you in there in a few minutes.”

As the promoter walked toward the dressing rooms, he said, “See, Roger, I told you he’d show.” Roger O’Gara, the sports editor of The Berkshire Eagle came over and introduced himself to Sugar Ray. He wanted to interview the old champion.

Sports writers used to come from all over the world to cover Sugar Ray’s big fights. Some of them would arrive a couple of weeks ahead and file stories every day out of Greenwood Lake or wherever he was training. At the weigh-ins with Basilio or Turpin or Maxim, there were more than 100 sports writers crowding around. But for this fight in Pittsfield, Roger O’Gara was the only one covering the weigh-in. He and Sugar Ray sat on folding chairs in the wooden grandstand. All around them were cigarette butts and empty peanut shells from the fight show two weeks earlier. Some of the people outside had followed them, and they stood around listening to O’Gara ask Robinson about his future and his past. When O’Gara was through, a local radioman, Pete Williams, wound up his tape recorder and put the small white microphone in front of Sugar Ray’s face. They talked for a few minutes. When that was over, Roger Sala, who was helping Silverman in the promotion, said, “That was important, Ray. It’ll be on Pete’s show at 6 o’clock. The people will know you’re here.”

Next to Sala among the bystanders was a wiry little man in a black pinstriped suit. He nudged Sala.

“Ray,” Sala said. “Here’s one of your greatest fans. George Ely. He never misses your Boston fights.”

George Ely owns a gas station in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, but when Sugar Ray Robinson is fighting nearby he takes the day off and gets dressed up as if he were going to a wedding. He could have driven over at night for the fight. But George Ely had to be there for the weigh-in, too.

“My brother,” Ely was saying now, “he used to fight on the same card with you in the amateurs in Thompsonville, Connecticut.”

“Thompsonvillel” Robinson said, laughing. “The old bootleg fights in Thompsonville! Ol’ buddy, that’s a long time ago!”

It was 1939. Three or four times a week Robinson and a few other kid fighters in Harlem would pile into George Gainford’s car and ride up to a town like Thompsonville, Connecticut. He was the Golden Gloves featherweight champion that year, but he fought in the bootleg shows, too, to make some sneaky money. He was born Walker Smith, Jr., but, as he always explains, “At first I wasn’t old enough to fight but this kid Ray Robinson was, so I took his name. I meant to give his name back but….” At one of these bootleg shows, in Watertown, New York, Jack Case, the sports editor of the Watertown Daily Times, told Gainford, “That’s a sweet-looking fighter you got there.”

“Sweet as sugar,” Gainford said.

The next day Case wrote of him as Sugar Ray Robinson. Somehow Sugar Walker Smith never would’ve had the same ring. “I don’t know haw many bootleg fights I had,” Robinson says. “Maybe a couple hundred.” The fighters weren’t supposed to get paid, but they did. “Maybe ten dollars if we won, maybe eight if we lost.” And when Sugar Ray reminisces about the bootleg fights, George Gainford always adds; “I made a living with them fights during the Depression.”

“Hey, Champ,” Gainford was saying, now in the runway at Wahconah Park. “They’re ready for you to weigh-in.”

“Excuse me, ol’ buddy,” Sugar Ray said to George Ely. “Good to talk to you. Thompsonville. Imagine that?”

Robinson walked around to a small cement-block office underneath the grandstand. Inside, four members of the Massachusetts Athletic Commission sat at a table.

The four men looked up at him and one of them began to ask the old champ the questions.

“Name?”

“Sugar Ray Robinson.”

“Manager?”

“None.”

“Date of birth?”

“May third, 1921.”

“May third,” said one of the men, about 35, “a good day.”

Robinson glanced at him.

“That’s my birthday,” the man said, “but not that year.”

“Well,” Ray said, shaking hands, “May third.”

When the questions ended one of the commission members held up a ball-point pen and a pad and said, “Excuse me, Ray, but my son would never forgive me if I didn’t get your autograph.”

“Glad to,” Ray said.

“One more thing,” one of the men said with a smile. “You haven’t weighed in yet.”

“Hey, that’s right,” Ray said.

On the floor was a green-and-black bathroom scale. Sam Silverman keeps it in the trunk of his Cadillac. Silverman was in the room now, leaning down to read the scale as Robinson stepped on it. Silverman was the only one in the room who could see the numbers.

“One sixty-one,” the promoter proclaimed. “Okay, Ray, go over to the hospital for a cardiogram.”

The commission members looked at each other but none of them said anything. Each wrote down 161.

“Mister, it’s my business to get him in trouble.”

Outside Sugar Ray got back in the station wagon and rode over to Pittsfield General Hospital. In the hospital a nurse said, “You’ll have to come back later. After three o’clock.”

“C’mon, George,” Sugar Ray said, “let’s get out of here. I don’t like hospitals.”

Sugar Ray never had to be carted into a hospital after a fight. He went to a hospital after one fight, though, the time he knocked out Jimmy Doyle in Cleveland in 1947. Doyle died and the coroner asked, “Robinson, didn’t you realize you had him in trouble?”

“Mister,” Sugar Ray said evenly, “it’s my business to get him in trouble.”

Two months later he boxed a benefit for Doyle’s family at the Garden. He was in with a welterweight from the Philippines named Flash Sebastian and he knocked him out with the first good right hand he threw in the first round. Sebastian went back against the ropes, toppled forward on his head and lay very still.

“My God,” one of the sports writers said at ringside. “This kid may be dead, too.”

Sebastian didn’t die, but when Sugar Ray knocked them out in those days people started to worry about them. People today worry more about Sugar Ray. Outside Pittsfield General Hospital, Robinson got back into the station wagon.

“We’ll come back later for the cardiogram,” he said to Tommy Brockett. “Let’s go to the ball park for the physical.”

The commission doctor was waiting for him in one of the cement-block dressing rooms underneath the grandstand. The doctor took his blood pressure and put a stethoscope on him.

“I examined you about ten years ago,” the doctor said as he finished. “You’re in as good shape now as you were then.”

Ten years ago Sugar Ray was making his comeback. When he retired after the Maxim fight, he was a rich man with prospects of becoming richer. Dun and Bradstreet gave him a $300,000 rating. He owned three four-story apartment buildings in Harlem. He owned a dry-cleaning shop, a lingerie shop, a barbershop and a café. And Joe Glaser, the theatrical agent, was booking him as a nightclub tap dancer for $15,000 a week. Only Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly ever made more with their feet. The night he opened in New York City’s French Casino he wore a yellow-and-black plaid dinner jacker with a black cummerbund. He did his dance routine and then he tried to tell a few jokes.

“There are three ways of communication,” he opened. “Telephone. Telegram. And tell a woman.”

With lines like that, Sugar Ray Robinson didn’t need bad reviews. Gradually his price skidded to $5,000 a week. Meanwhile one of his advisers had developed a better act: he was making at least $250,000 of Sugar Ray’s money disappear. “By the time I discovered it,” Robinson once explained, “the man was dead.” Sugar Ray returned to the one thing he knew could make big money for him: fighting. He started out by knocking out Joe Rindone but then he was outpointed by Ralph (Tiger) Jones. He wasn’t much better in winning a decision over Johnny Lombardo in Cincinnati. That night he sat on his hotel bed and cried.

Joe Glaser and his manager at the time, Ernie Braca, were trying to convince him to quit. But another adviser Vic Marsillo barked “Don’t listen to them. Listen to me. You’re going to win the title again.” One night about eight months later he caught Bobo Olson with an uppercut in the second round. The knockout made him the middleweight champion.

During his comeback, the big paydays with Carmen Basilio and Gene Fullmer and Paul Pender helped earn him close to $1,500,000 in purses. But early in 1962 he lost a decision to a kid named Denny Moyer, and everybody soured on him. He lost to Phil Moyer, too, and to Terry Downes in London. In June, 1963, he had his last fight with a big-name opponent, losing a decision to Joey Giardello in Philadelphia.

Some weeks later Sugar Ray sat down with George Gainford.“Try it with me once more,” the old champion pleaded. “Just once more.” George Gainford is a big, barrel-chested man who is known among boxing people as The Emperor. Except for a few spats, he has been watching over Sugar Ray Robinson since the day almost 30 years ago when Walker Smith, Jr., came in off the street to learn to box at the Salem-Crescent Gym in Harlem.

“Let’s go, Robinson,” Gainford was saying now in Pittsfield as Sugar Ray tucked in his shirt after the physical. “You got to eat.”

They got in the station wagon and Gainford told Tommy Brockett, “We’re going to eat. There’s a Howard Johnson near the motel.”

As they drove, Gainford said, “Turn on the radio. It’s three o’clock. Ought to be a weather report.” It had been sunny an hour earlier, but now the clouds were gray as they came over the mountains from the west. “Sam say to be there early,” Gainford said. “If it looks like rain, he’ll put us on first at 8:30.”

This is an old gimmick. Once the feature bout is over, the promoter doesn’t have to make any refunds.

“The weather,” the radio announcer was saying, “tonight, cloudy with a chance of thundershowers.”

“Hear that, Robinson,” Gainford said. ‘We gotta be out of the motel at eight o’clock. No later.”

They used to turn this many away years ago when Sugar Ray had a big fight at Madison Square Garden.

As they left the restaurant Sugar Ray was singing, “‘People … people who need people … are the luckiest people.’ ” He has been taking voice lessons for about five years. “Richard Rodgers got me started,” he was saying. “He heard me one day and he couldn’t believe I never had any voice training. My teacher, Jaharal Hall, tells me I’ve got to sing like I fight—smooth, no apparent effort.”

The station wagon stopped at the hospital again. Gainford went in first, Soon he was back. “We’re okay this time,” he said. “Fourth floor.”

Sugar Ray disappeared through the doorway to the stairs. “He never takes elevators,” Gainford was saying as he pushed the elevator button. “One time in Brussels he had to walk up 52 flights.” When the elevator opened on the fourth floor, Sugar Ray was coming through the stairway door. “When I was little,” he explained, “I got sick once in the elevator in the Empire State Building. Never rode in one since. You run four, five miles a day almost every day of your life, stairs don’t tire you out.” After the cardiogram he walked down the stairs.

At two minutes after eight Gainford came out of the motel room with four pink motel towels over his arm and glanced at the sky. “Looks pretty good,” he said. “Not as gray as before. We be all right.” Moments later Sugar Ray came out. As the station wagon moved out of the parking lot, a voice near the motel office yelled, “Good luck, Champ,” and Robinson turned and waved out the window. They rode through Pittsfield. Outside Wahconah Park the parking lot was almost half filled.

They used to turn this many away years ago when Sugar Ray had a big fight at Madison Square Garden. The mounted policemen’s horses would be clamping along the macadam pavement on Eighth Avenue and the people would be getting out of taxis six blocks away to walk through the traffic jam. Now, at Wahconah Park, there were a handful of people around the front gate—the only gate—when Sugar Ray went through.

At the gray wooden ticket booth there were six people on line. There were three prices: $2.50, $2.00 and $1.50. Once, at Yankee Stadium, the ringside seats were $40 a pop when he fought Carmen Basilio the first time. That night he had the big Yankee clubhouse, with its green wall-to-wall carpeting, all to himself. But in Pittsfield now he walked into a small, low-ceilinged dressing room he would share with four preliminary fighters.

The room was crowded. The preliminary fighters were there, wearing their satin robes and sitting on the wooden benches. One of them said, “Mister Robinson” and introduced himself, and Sugar Ray shook hands with him and said, “Good luck, ol’ buddy.” Three sports writers had followed him in.

Sugar Ray hung his lime slacks on a wire hanger in his unpainted wooden locker. He put his boxing shoes on and then he began to tape his hands, first wrapping them with a few layers of gauze, then with the white adhesive tape.

“You do that yourself?” a sports writer asked.

“Been doin’ it for 20 years,” Robinson said with a smile.

“One more question,” the writer said. “Why do you take a fight in a town like this?”

“You need fights like this,” Sugar Ray said. “You can’t fight in the Garden all the time.”

He hadn’t had a fight in Madison Square Garden in more than a year. And he’ll never have another one there. The Garden won’t use him. It’s too obvious an exploitation of a famous name. And suppose he got hurt? Or worse?

“Well,” one of the sports writers said, closing his notebook, “good luck in the fight tonight.”

When they left, he took off his white net shorts and put on a jockstrap and a white terry-cloth fingertip robe. The sleeves were slit to the elbows. He took a blue bottle out of the suitcase. The bottle contained an eyewash named Collyrium. He poured a capful, tilted his head back and bathed his right eye, then his left. “You ought to do this,” he said to one of the preliminary kids, “it protects your retinas.” He went into the shower room and shadow-boxed for a few minutes. When he returned, he put on a brown leather cup over his jockstrap. “Had this since the Golden Gloves,” he said proudly. “See how it’s all taped up. Had to rebuild it several times.”

Sam Silverman came into the room and said, “Let’s get out there, Ray. They’re waiting for you. Let’s go, Ray.”

Gainford tied the laces on Sugar Ray’s reddish-brown gloves. He helped him into a blue satin robe with SUGAR RAY in white letters on the back. He draped one of the pink motel towels over Robinson’s head and tucked it inside the lapels of his robe. “Okay,” George said, “let’s go.” Outside the dressing room maybe 20 people were waiting for the old champion, and they followed him out around the third-base end of the stands and watched him jog through the aisle between the ringside seats.

There were maybe 1,500 people in the ball park and they shouted when Ray hopped up the wooden steps and climbed through the ropes into the ring.

This used to be one of the most exciting moments in sports. There always were movie stars and politicians in the ringside seats when Sugar Ray had a big fight. And the old champions—Dempsey, Louis, Tunney, Mickey Walker, Barney Ross—would come into the ring and take a bow after the announcer introduced them. The announcer always wore a tuxedo. But in Wahconah Park the announcer was wearing a brown sports jacket with a golf shirt open at the neck and he was saying, “And now a big hand for the Sweetheart of the Berkshires, Frankie Martin,” and a little old lightweight jumped into the ring and waved his hands. Now, for the first time, the people began to look at Sugar Ray’s opponent. Clarence Riley, a lanky, loose-muscled middleweight out of Detroit, was standing in his corner looking across at Sugar Ray almost in awe. He has been around since 1951 but out of 30 fights he had only won 14. Even with a seven-pound weight advantage at 168, he was the perfect opponent, as they say in boxing, meaning someone whose ability doesn’t give him a chance to win.

When the bell rang, Sugar Ray turned and strutted into the middle of the ring, his slim legs moving gracefully and his white satin trunks shimmering under the overhead lights.

Gainford crouched on the steps behind the corner. “Too wild,” he shouted during the early rounds. “Steady as she goes now, steady.” In the fourth Sugar Ray threw two quick left hooks and Riley went down. His lips were puffed and bleeding and he was sitting down with his hands behind him. The crowd yelled, and when Riley got to his feet Gainford shouted, “Uppercut him now, uppercut.” The bell rang and John Seymour, holding the water pail, nudged the man next to him and said, “You see those left hooks. Like old times. Like old times.” In the fifth Sugar Ray put Riley down again with a flurry of body punches and a straight right hand. In the sixth Riley went down again from a left hook. He was up at nine but he was wobbling, and Gainford was yelling, “Stop it, ref, you going to get this kid hurt.” The referee put his arms around Riley and the fight was over.

It was in the book now: his 160th victory (his 103rd knockout) against 12 losses. At Wahconah Park the people were yelling, “You’re still the best, Sugar,” and, “You look great, Champ.”

Robinson didn’t seem to hear them. He stood in his corner while Gainford wrapped the blue satin robe around him and stuffed one of the pink motel towels around his neck. Then Sugar Ray came down the steps and moved through the crowd back to the dressing room. Inside he sat on the wooden bench and held out his hands for Tommy Brockett to cut the tape off and talked to the sports writers. Off to the side a radioman was holding a tape-recorder microphone up to George Gainford’s face.

“Those left hooks,” Gainford was saying. “Two left hooks in a row. You don’t see that today in boxing. Nobody does that. Nobody but this man.”

Half an hour later some of the crowd were waiting for Robinson as he came out of the dressing room. He signed autographs for them, and then he walked into the gray wooden ticket booth to pick up his money from Sam Silverman. It took him 20 minutes. Sugar Ray has always enjoyed haggling with promoters.

“We’ll guarantee you a half a million,” Admiral John Bergen of Madison Square Garden once told him, “for a third fight with Basilio.”

“Admiral,” Robinson said, “I got a theater-TV deal cooking that’ll get me three quarters of a million. I got to go for that one.”

The theater-TV deal went sour. He wound up with no fight and, worse, with no money. In Pittsfield at least he came out of the ticket booth with some cash. “About $700,” Silverman said later. Years ago that wouldn’t have covered the booze for a victory party in Robinson’s Harlem café. He doesn’t drink, but he would stay up tap dancing and playing the drums. Somebody would bring in the late editions of the morning papers and he’d look at the headline—SUGAR RAY BY KAYO—and read the stories and look at the pictures. But this fight in Pittsfield didn’t even make a paragraph in the New York morning papers.

Three weeks later Robinson would fight a draw (his fifth) with a kid named Art Hernandez in Omaha. In September he would lose (for the 13th time) to Mick Leahy in Baisley, Scotland. Then he took a hotly disputed decision from Yoland Leveque in Paris.

The farce will go on. Sugar Ray’s name will keep popping up in the small-print, one-line fight notices in newspapers. And for a few seconds in every fight he will throw those left hooks and some fans will be fooled into thinking they’re seeing the real thing.