The best thing about fall in an urban environment, aside from the sight of a few burnished leaves, must be those delicious attacks of nonspecific, free-floating, and undirected lust. It’s not an oft-mentioned phenomenon, but most of us who live in New York know it occurs here in a particularly poignant form, and it’s one of the many reasons (undecipherable to ignorantly condescending out-of-towners) that people stay in this city. I don’t know why it happens; maybe it’s the crispness in the air and so forth. Maybe it’s the clothes, I don’t know.

For women of a certain age (which seems to be younger and younger lately), fall’s a wonderful metaphor, too. I mean, unless you’re having a very, very, very bad day and you’re waiting for winter for an adequately dismal metaphor. But if you’re having your average autumn-in-New-York day—filled with stress, excitement, and ineffable vestigial longing for romance—your only problem is figuring out what to do with such longing. Of course, part of the point of the longing is that it’s undirected. Or you might say part of the point of longing is simply to long (since longing, by definition, cannot be fulfilled or it disappears, though I don’t know about you, but it makes me cosmically nervous to think about that; it’s like one of those weird astrophysics things about having to accept that there’s nothing in space, or that there’s space in nothing, or one of those).

Anyway, if this sounds even remotely familiar—that is, if you’ve got some extra free-floating longing and you’re looking for a spot to park it a while—don’t wait a single second to go see My Own Private Idaho, the latest movie from Gus Van Sant, the director of Drugstore Cowboy. It’s the best movie I’ve seen in a very long time. It’s beautiful to look at, it’s whimsical, it’s well-acted, it’s moving, it toys exquisitely with the boundaries of form. But aside from all this, it offers a wonderful objective correlative for this yearning thing. Check out young River Phoenix and you’ll see what I mean.

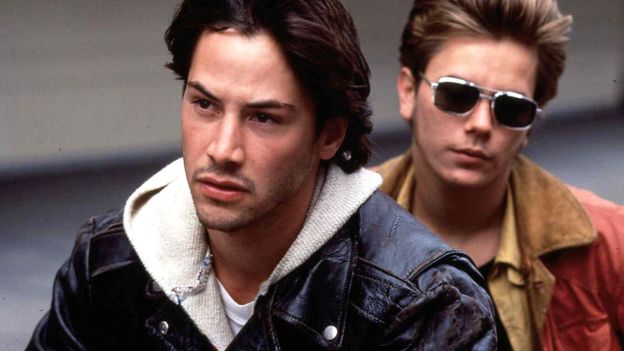

It’s not just that this kid is kind of great looking. There’s also the extremely pleasant voyeuristic thrill of this astonishingly intimate look at a young male hustler’s life as he’s turning tricks or hitchhiking on the open road with or without his (equally delicious, also ambisexual) buddy, played by Keanu Reeves. But more than that, it’s the pleasure of allowing oneself to connect with this character who’s pure seduction, American-style, with all the delicate panache, hipness, loneliness, and wild raunchy tenderness that American film stars can display. It’s a great stroke of luck for us, I think, that as it turns out, one of the most enduring American legacies is that of James Dean, the lonely, tender, delectably androgynous wanderer wearing perfect jeans. Every once in a while, just as we’re about to give up hope, he surges up again, out of the rich bin of weird American fantasies. In this case he’s a narcoleptic hustler looking for his mother, but hey, aren’t we all?

He’s a perfect target for unrealizable desire. You can’t ever go to bed with this guy: he’s too young, he’s too scruff, and you suspect he’d prefer your kid brother to you. In fact, one of the reasons you’re beguiled by this character’s erotic personality is that you can’t define it. It may be an advantage that his sexuality is not complementary with ours: these days, in movies and in life, as soon as any adult heterosexual falls in love with any other adult heterosexual, mortgage rates become a secondary plot element.

In any event, it may be that it’s precisely everything that’s culturally and sexually different about the wanderer that enables us to connect again with that part of ourselves which has gotten atrophied in the getting and spending and the exhausting exigencies of adulthood, to reexperience not just the journeying and the wildness that made youth so painful and so much fun but also the beating, just a few layers down, of a sweet and loving heart. In one scene, the two boys are (where else?) camped by a fire alongside the road at night, talking about wishing they could love each other in a way that men can’s: in the young hustlers’ emotional vocabulary, they can have sex together, but not love. “I really want to kiss you, man,” one of the boys says to the other. It’s somewhat disingenuous dialogue, in these days of gay power. But there’s an emotional truth to the scene, in the boys’ longing for each other’s comfort, that transcends temporary cultural verities as well as generation gaps and the endlessly tedious logistics of life in the ’90s. It’s like the longing for everything we can’t have, in Idaho or in New York, that precious longing that keeps us young when it springs up, incongruous and painful but welcome, one fine fall day, sort of like a desert flower.