Under the cover of the lengthening shadows of a sleepy August afternoon in 1915, five Model T’s loaded with armed men quietly departed the northwest Atlanta suburb of Marietta. The men had told their wives they were going fishing. But this was no ordinary group of anglers. To avoid identification, several members of the party—whose number included mechanics, telephone linemen, explosives experts, a doctor, a preacher, and a lawyer—wore leather goggles. To escape detection, the drivers took different back roads out of town. By the time light was gone from the summer sky, the men were alone in the Georgia countryside, barreling south through cotton fields toward Milledgeville, 175 miles away.

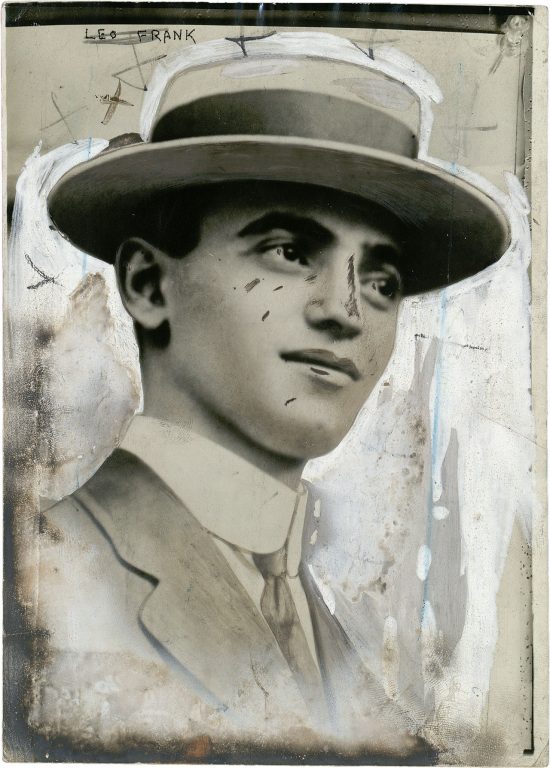

In his quarters at the Georgia State Prison Farm just outside Milledgeville, Leo Max Frank lay in bed. A nervous, circumspect Brooklyn Jew whose bulging eyes and wiry build lent him an unfortunate resemblance to a praying mantis, Frank had been convicted in 1913 of killing Mary Phagan, a thirteen-year-old Marietta girl who worked for him at the National Pencil Company in Atlanta. Frank had been condemned to die for the crime, and his conviction had been upheld by both the Georgia and the United States supreme courts. Nevertheless, Georgia governor John Slaton believed the evidence was inconclusive—on June 21, 1915, the eve of Frank’s execution date, Slaton commuted the sentence to life imprisonment. That night an angry mob marched on the governor’s mansion, burning Slaton in effigy. “Our grand old Empire State HAS BEEN RAPED!” wrote Tom Watson, the legendary populist editor of The Jeffersonian. “Hereafter, let no man reproach the South with Lynch law: let him remember the provocation; and let him say whether Lynch law is not better than no law at all.” Four weeks after the commutation, one of Frank’s fellow inmates attacked him in his sleep, slitting his throat with a butcher knife. If another prisoner, a surgeon convicted of murder, hadn’t stitched Frank’s wound, he would have died.

Still, as the early evening hours of August 16 wound down, Frank remained hopeful. The seven-and-a-half-inch gash around his neck had healed quickly, and he’d written a friend that his survival was a sign that the worst was over and vindication was near. In his battle for exoneration, Frank was counting heavily upon a campaign being waged in his behalf by northern Jewish leaders, among them Adolph Ochs, publisher of The New York Times. Frank also took faith from the support of his wife, Lucille, whose steady stream of letters always promised a happy ending.

But Leo Frank’s fate was not to be a pleasant one. By 11:00 the men who had left Marietta at dusk had completed their trip and reconnoitered with two advance scouts just outside the prison. The group’s commander, the scion of a powerful Marietta family, calmly issued orders, and with military precision the men began their work, cutting telephone lines, overpowering guards, handcuffing the warden, and finally moving directly to Frank’s dormitory, where the prisoner was roused from his sleep and quickly hustled outside.

Within minutes, the kidnappers roared off, vanishing onto unmapped highways. The raiders were not seen again until just before dawn, when two farmers walking through a field south of Marietta looked up and saw a series of cars—goggled drivers covered in red dust; Frank, his face unprotected, conspicuous in his nightclothes from where he sat between two captors in the back of one of the vehicles—racing against the coming of the day. The motorcade’s destination was the Marietta courthouse square, but with the sun rapidly rising, the cars came to a halt in a grove near Frey’s Gin, at the edge of town. During the journey Frank had convinced several of his abductors that he was innocent, and thus a tense debate broke out. Following several sharp exchanges, the faction advocating mercy was overruled.

“I think more of my wife and my mother than I do of my life,” Frank whispered as he was marched to a large oak tree, blindfolded, and ordered to stand on a table.

“Mr. Frank,” said the group’s leader, “we are now going to do what the law said to do—hang you by the neck until you are dead. Do you want to make any statement before you die?”

At first, Frank shook his head no, but he reconsidered and asked that his wedding ring be returned to his wife.

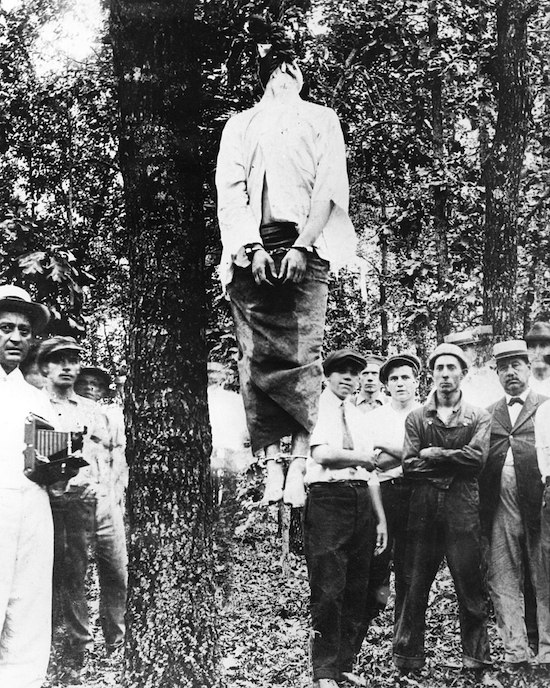

A noose was then tied around Frank’s neck, and the table was kicked out from under him. Its job finished, the lynch party hastily disbanded.

As word spread that Leo Frank’s body was twisting from a limb on the outskirts of Marietta, a crowd formed. They pecked at Frank’s corpse, tearing away his nightshirt up to the elbows. Then someone cut the dead man down and began to grind a heel into his face. At the last instant, a judge who had arrived on the scene took control, rescuing the body from the mutilation that was sure to come. All the while, photographers snapped pictures.

These photographs were once commonplace in the South. One of them, shot from behind a semicircle of gawkers, offers a sickening view of what hanging does to a man: Frank’s head is snapped back at a 90degree angle so that his eyes, beneath their blindfold, stare heavenward. His chin rests awkwardly on four neat coils of rope that knot off the noose. His neck is hidden by his collar, but the fabric can’t disguise that his throat muscles have ripped and stretched like taffy. His hands are bound in front of him, and his manacled feet swing in the air about a yard above the ground.

As time went by, the pictures—like the topic of Frank’s lynching itself—became curiosities, usually found behind counters in country stores, way back behind dusty jars of pickled pigs’ feet and discarded Slim Jim boxes.

In the shots taken from another angle, the faces in the crowd come into focus. Some belong to jowly townies. But most are those of sunken-cheeked, nine-fingered rustics in bib overalls held up by galluses. One—jug ears, thin lips, sallow complexion—bespeaks the ravages of moonshine. Another—lopsided jaw, crooked mouth, unfathomably stupid eyes—conjures up the eerie sound of a banjo string tuned to the breaking point, a note of backwoods madness.

As time went by, the pictures—like the topic of Frank’s lynching itself—became curiosities, usually found behind counters in country stores, way back behind dusty jars of pickled pigs’ feet and discarded Slim Jim boxes. Yet in these obscure niches the photographs performed a function. They said that Leo Frank was lynched by crackers in one of those spontaneous strikes of vigilantism usually reserved for a drunken black who’d committed the capital offense of stealing a mule.

But the men who murdered Leo Frank were not ignorant Snopeses caught up in a racist frenzy. They were Marietta’s leading citizens, and they acted premeditatedly and without passion. After the lynching one of the first things they did was preside over the perfunctory grand jury hearing that swiftly absolved the town’s population of any guilt in Frank’s death. The twenty-five men who participated in the incident swore one another to secrecy, and their names were never reported. In higher circles around Marietta, though, their identities were generally well known, for they had nothing to fear. They had been inspired, it was believed, by a deep moral necessity. Just hours after the lynching an anonymous individual who was very likely one of Frank’s killers told a reporter: “This modern exploit [was] done in the interest of justice.” This was the word they called it down through the years.

On a misty winter afternoon three days before Christmas 1983, a frail, white-haired man wearing an old raincoat over his best brown Sunday suit walked slowly across the lawn of the Georgia capitol building in Atlanta. When he reached the statue of Tom Watson that stands at the western entrance to the seat of government, the man paused and contemplated the figure of the person who, more than any other, had created the atmosphere in which Leo Frank’s lynching could be termed justice. Then Alonzo Mann, eighty-five, headed up the capitol steps on his own mission of justice. On a summer day seventy years earlier, Mann had failed to tell Leo Frank’s trial jury what he believed to be the truth: Leo Frank was not guilty; someone else had murdered Mary Phagan. On Saturday, April 26, 1913, the day the girl was killed, Mann had barged into the National Pencil Company, where he was the office boy, and seen the real culprit toting Mary Phagan’s body like a sack of potatoes. According to Mann, the Mariettans who lynched Leo Frank had not only committed the crime of murder, but they had hung an innocent man.

For a lifetime, Alonzo Mann had carried his secret with him. At first, he says, he was too scared to repeat it. When he grew older, he claims that he did tell a few people, yet they ignored him. But finally he had found someone who would listen. One year before this gray holiday afternoon, Mann had sat down with attorney John J. Hooker, a debonair financier and unsuccessful Tennessee gubernatorial candidate. Hooker had agreed to take Mann’s deposition. After establishing the ground rules, he led his witness into the past, directing Mann to the scene that had haunted him for seventy years.

“I opened the door to the National Pencil Company and walked in,” Mann said in a soft, sure voice.

“What time was that?” Hooker asked. “I think it was a little after 12:00….Then I looked up to the right, and there was Jim Conley with a girl in his arm and she was limp.”

“Who was Jim Conley?”

“Jim Conley was a sweeper or the porter, you might want to call him.”

“Was he a white man or a black man?”

“No, he was a—kind of mulatto.”

“But he was a Negro?”

“Yes. He looked around at me. He couldn’t reach me….He says, ‘If you tell anything about this, I’ll kill you.’….So I turned around and went out the door and went home.”

Hooker took a deep breath. Then he began to read from an affidavit Mann had given The Tennessean in Nashville. (Tennessean reporters Jerry Thompson and Robert Sherborne had published the first newspaper account of Mann’s story on March 7, 1982.)

“‘He had the body of Mary Phagan in his arms,’” Hooker read.

“Yes, he had the body of a young lady in his arms,” Mann answered.

“‘She appeared to be unconscious or perhaps dead.’”

“That’s right.”

“‘I saw no blood.’”

“That’s correct.”

Hooker paused.

Then he asked, “Now, Mr. Mann, when you got home, what did you tell your mother?”

“I told my mother what happened, and she says, ‘Don’t say anything about it, and we will wait and see how it comes out.’ So the next morning they find Mary Phagan and my mother says, ‘Don’t say anything about it because we don’t want to get involved in it.’”

Mann told Hooker that he had obeyed his mother’s request. He was that terrified of Jim Conley, and his parents were that terrified of the hostility their son might attract if he came forth. Now, Mann confided, he was obsessed by another fear: he was afraid that he was going to carry the burden of not speaking out to the grave.

This was the crux of Mann’s statement, and it became the foundation for an application that Charles Wittenstein, southern counsel for the Anti-Defamation League, and Dale Schwartz, a partner in the Atlanta law firm of Troutman Sanders, would file with the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles. The two attorneys were going to reopen the pages of history by seeking a posthumous pardon for Leo Frank.

Alonzo Mann, of course, was not the first person to raise questions about what had happened to Leo Frank. Over the years a number of historians and journalists have attacked various aspects of Frank’s trial and the lynching. But Mann’s statement was the strongest evidence yet produced against the one figure in the case whose story has been disputed by almost everyone who believes in Frank’s innocence: Jim Conley, the prosecution’s star witness and the first black man ever whose testimony was accepted over a white man’s in a capital case in the South.

For a year the members of the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles had pondered the Frank pardon request. Finally, on this December day in an age lightyears removed from the morning of Frank’s lynching (in 1915, the Lusitania was torpedoed, Rasputin held sway in the czar’s court, and Ty Cobb hit a mere .369), they had reached a decision. This was why Alonzo Mann was at the Georgia capitol.

On the Saturday in 1913 that Mary Phagan would die, Atlanta was already the center of the New South. The skyline contained a formidable collection of aspiring towers, and local banks were overflowing with Yankee capital, some of which had gone to start the National Pencil Company on Forsyth Street. It was here that twenty-nine-year-old Leo Frank arrived on the chilly morning of April 26 to go over his ledger books in his second-story office.

Shuttered away with cheap cigars and neat columns of figures, Frank—who had been educated at the Pratt Institute of Design and Cornell University—was at one with the forces that had gained control of the city. But bright and ambitious though the pencil-factory superintendent was, he was also, in any final analysis, an alien—a northerner who would never comprehend the embittered past upon which the new prosperity was erected.

April 26 was Confederate Memorial Day, and Peachtree Street, two blocks east of Frank’s factory, was lined with thousands of native southerners come to praise the lost cause. There was a parade with scores of children in white caps and shirts followed by six thousand aging veterans who carried before them regimental banners and ragged Stars and Bars that had been torn by shrapnel at Gettysburg. Celebratory of the old order and commemorative of those who died to save it, the ceremony could also well be seen as a protest against the confusing maelstrom of change transforming Dixie from an agrarian to an industrial society.

Around 11:30 that morning, Mary Phagan caught a trolley into town. Pretty, plump, and precocious, she wore a pastel violet dress and a hat adorned with fresh flowers. In her hands she carried a mesh purse and a parasol. Shortly before noon she stepped off the car and walked to the nearly deserted pencil factory; after picking up her wages, she intended to go and watch the parade.

At about 12:05 the young girl appeared in the doorway of Frank’s office, and Frank handed her an envelope that contained two silver half-dollars and two dimes—ten hours’ earnings. Mary Phagan had not worked much during the previous week. Her job, putting eraser caps on pencils, had temporarily been canceled because of a delayed metal shipment.

“Has the brass come in yet?” she asked Frank in parting.

It was now nearly 12:10, and what happened in the factory during the next few hours would forever be disputed. The few inarguable facts are these:

After eating lunch at home around 1:00, Frank returned to work and finished several complicated pieces of accounting. He also wrote his uncle a letter that included the line: “It’s been too short a time since you left for anything startling to have developed down here.”

At 4:00 P.M., when the night watchman, a black man named Newt Lee, arrived early for work, Frank told him to leave and come back later. Lee said he’d rather go to sleep in the basement until punch-in time, but Frank insisted, encouraging Lee to “go out and have a good time.”

At 6:00 P.M. Lee returned. Presently, Frank locked up and headed home to the southeast Atlanta residence of his wife’s parents, with whom the Franks lived.

At 7:00 P.M. Frank did something he’d never done before—he telephoned Newt Lee to ask if things were all right. The guard said they were. Frank retired to the parlor, and guests soon arrived to play bridge. As the cards were dealt, conversation focused on the opera, which Frank’s mother-in-law and Lucille had attended that afternoon. When Frank chose to, he could be engaging, but tonight he was withdrawn and went to bed early.

Around 3:00 A.M. Newt Lee—who had spent the night making rounds of the upper stories of the factory—stepped down a ladder into the basement, a dark chamber that smelled of wood shavings and lead. Holding a lantern before him, the watchman soon spotted what looked like a body sprawled on the floor near the furnace. He climbed back up the ladder and phoned Frank’s house. No one answered. Then he called the police. Within minutes, three officers arrived, descended the ladder, and found Mary Phagan. She had been strangled to death with a piece of twine. She had also been cut on the back of the head, her face was bruised, and her fingernails and mouth were gritty with coal dust and pencil parings. There was blood on her underwear, but an autopsy would determine that she apparently had not been raped.

Later in the morning the police discovered two notes that had been clumsily scrawled on out-of-date pencil-company order forms and placed beside the body. They read:

“he said he wood love me and land down play like night witch did it but that long tall black negro did boy his slef.”

“Mam that negro hire down here did this i went to make water and he push me down that hole a long tall negro black that hoo it wase long sleam tall negro i wright while play with me”

Nowhere to be found were the mesh purse or the $1.20 in wages, but at the bottom of the factory elevator shaft were a girl’s hat, a ball of twine, a parasol, and a mound of human excrement. Later that day when the police took the elevator car down to the basement, all of these items were crushed, releasing a nasty stench.

Newt Lee—a “long tall black negro”—was the first suspect arrested in the case, but Leo Frank aroused the police department’s suspicions from the outset. When detectives appeared at his door on Sunday morning, Frank was standoffish, arguing that he wanted a cup of coffee before he would accompany the lawmen. When the urgency of the matter was impressed upon the factory superintendent, he reluctantly agreed to venture out. The first stop was the morgue, where Frank recoiled from the sight of Mary Phagan’s corpse and said he couldn’t identify her. With nearly one hundred young women laboring for him, how could he be expected to remember them all? Then Frank was driven to the pencil company, where a search of his records revealed that Mary Phagan had indeed been the worker he’d paid on Saturday. Frank was the last person to admit seeing the girl alive.

On Monday Frank was questioned in the office of Chief of Detectives Newport Lanford. When he realized that he might be a suspect, Frank stripped off his shirt in the hope that his unscratched torso would convince the detective that he couldn’t have committed such a brutal murder. Then he invited officers to examine his laundry at home for bloodstained garments. The search was conducted, and it revealed nothing. But the police were still curious. Before the day was over, Frank had retained a lawyer and hired Pinkerton’s detective agency to find the killer.

Over the next few days Atlanta’s three newspapers—The Atlanta Constitution, The Atlanta Journal, and the Hearst-owned Atlanta Georgian—urged the police department to act quickly on “the case of Little Mary Phagan.” The Constitution editorialized: “The detective force and the entire [sic] police authorities are on probation until the detection and arrest of this criminal with proof.”

Protesting that he was innocent, Frank was arrested on April 29 after the discovery of some hair and blood drops on the floor of the pencil factory’s second-story metal shop—the site where the prosecution would allege Frank strangled Mary Phagan after luring her there on the pretext of ascertaining whether an order of brass had arrived. Frank was imprisoned in the Fulton County Jail, an old brick lockup known locally as the Tower. For the first few days of his incarceration Frank refused to see his wife, saying that he couldn’t stand for her to visit him behind bars. This self-imposed isolation was generally regarded by Atlantans as evidence of Lucille’s awareness of her husband’s culpability. Later, even though Lucille began making daily pilgrimages to the Tower, Frank was unable to dispel this perception. In fact, he never really tried. He refused to grant interviews to reporters and spent most of his time going over his company’s books. In Atlanta’s newspapers he was given a forbidding sobriquet: the Silent Man in the Tower.

While Frank awaited trial—too stunned, too arrogant, or too cautious to speak out on his own behalf—another man confined to a different Atlanta jail was talking freely.

Two days after Frank’s apprehension, Jim Conley was detained when he was seen in the pencil-factory basement washing out a shirt soaked with what appeared to be blood. At first, neither the police nor Solicitor General Hugh Dorsey paid much attention to the new prisoner. But when investigators were tipped that Conley could write, he became a prime suspect in the penning of the two curious notes found by Mary Phagan’s body.

Over a two-week period in May, Atlanta police officers interrogated Conley. The “sweating” began on a Sunday afternoon when Conley was locked in a six-by-eight-foot room by Detective John Black and Detective Harry Scott, the Pinkerton agent Frank had hired (Scott, who played both sides of the fence, ended up becoming Frank’s Judas).

“Well, Jim,” The Constitution reported Black saying, “we’ve got the deadwood on you.”

“Honest, white folks, I swear ’fore God and high heaven I don’t know a thing,” Conley replied.

“Listen,” asked Scott, “can you write?”

“No,” Conley said, “and I never could.”

Scott then shoved a jewelry bill that bore Conley’s signature in its author’s face. Conley was wordless. Finally he said, “White folks, I’m a liar.”

Conley proceeded to write out the ABC’s, after which the detectives asked him to copy something down for them.

“That long tall black Negro did this by himself,” Black dictated.

“That long tall black negro did this boy his slef, ” Conley laboriously wrote, making the same misspellings prominent in one of the murder notes.

The detectives stared at the prisoner, then walked out of the room.

Conley—a short, stocky, ginger-colored Negro—was surely experienced in such cat-and-mouse games. At twenty-seven, he had been convicted of several minor offenses and served a couple of sentences on the chain gang. But canny though he may have been, Conley was very probably also scared. Deep in his cell, he must have felt the oppressive weight of the white South falling upon him, grinding him down until he was nothing but a lump of coal. And the pressure didn’t stop there. It kept mounting, pushing him into a corner with a crushing force until he formed the diamond of deceit that would glitter at the center of the prosecution’s case against Frank.

As Frank’s trial date drew near, both the prosecuting attorneys and the defense lawyers marveled at Conley’s story, and, for different but equally racist reasons, each side decreed it good.

Several days after the initial grilling, Conley summoned Detective Black. “I’ve got something to tell you, boss,” he said. “I wrote those notes. Mr. Frank had me write ’em. I didn’t know what he wanted with them, and he gave me some money to do it.” Conley also told Black that Frank had planned the murder in advance, dictating the notes on the Friday before the killing after muttering, “Why should I hang? I have wealthy people in Brooklyn.”

This was only the beginning. The admission of authorship in hand, the investigators pushed their advantage. Under careful coaching, Conley would produce three affidavits that, while contradictory in parts, agreed on the main point: Frank killed Mary Phagan and then conspired with Conley to dispose of the body and write the notes in the hope that they could pin the crime on Newt Lee. Conley would contend that on the day of Mary Phagan’s death he had been “watching out” for Frank, something he often did while his boss “chatted up” little girls. He would say that Frank asked him to load Mary Phagan’s body into the elevator and transport it to the basement. Finally (after being informed that it was unlikely that Frank composed the murder notes on Friday, as the crime bore no signs of forethought), he would improve upon his initial story, saying that it wasn’t until after he had dumped the body and returned to Frank’s office that he actually took down the notes.

As Frank’s trial date drew near, both the prosecuting attorneys and the defense lawyers marveled at Conley’s story, and, for different but equally racist reasons, each side decreed it good. In prosecutor Dorsey’s mind, the fact that Conley had produced several variations of his tale was confirmation of the narrative’s veracity: Conley was a lying nigger and lying niggers couldn’t get a story straight the first time or the second, but give them one more shot and they’d sure see the light. Meanwhile, Frank’s defense counsel salivated at the prospect of cross-examining Conley, believing that no nigger could retell such a convoluted chronicle in the right order.

Leo Frank’s trial began on July 28, 1913, in a makeshift courtroom on the first floor of Atlanta’s City Hall in the midst of one of the worst heat waves in Georgia history. The temporary chamber, while set up with the traditional bench and railings and outfitted with several cumbersome ozonators (primitive precursors of the air conditioner), was crowded and oppressive. The judge, jury, legal teams, and spectators sat practically on top of one another, and after the first day the windows were thrown open in the futile hope that fresh air would circulate through the room. Instead, the proceedings were simply more accessible to the hundreds of rubberneckers who either stood in the streets or squatted like crows on the hot tar-paper roofs of several warehouses directly behind the judge.

When Leo Frank and his family appeared in court on the first morning of the trial, they made no attempt to disguise their expensive taste in clothing. The accused wore a gray mohair suit with a sharp silk tie. Lucille wore black silk and lace, and Frank’s mother, Rhea, who had journeyed south from Brooklyn to protect her son, wore a stylish long white dress clasped at the neck by a cameo. Frank’s attorneys—Luther Rosser and Reuben Arnold, Atlanta’s two premier trial lawyers—were both southern gentiles, but they, too, evoked the posh, brocaded world of the big city.

On the other side of the aisle, Mary Phagan’s mother, dressed in the simple garments of a poor country woman, sat behind the prosecution table, which was staffed by the state’s attorneys. Hugh Dorsey was a passionate Huck Finn whose dark hair fell into a cowlick on his forehead. He was assisted by Frank Hooper, a southwest Georgian with a parched complexion and sandy bangs. Also sitting with the solicitor was a young lawyer named William Smith, who had been preparing his client, Jim Conley, for the witness stand.

Throughout the early days of the trial, both sides scored points. Hugh Dorsey introduced testimony from a young female factory worker who said she’d arrived at Frank’s office a little after noon on April 26 and found it empty—suggesting that Frank could well have been off with Mary Phagan. Meanwhile, the defense decimated the allegations of a boy who contended that Mary Phagan had confided her fears of Frank to him. But in spite of Rosser and Arnold’s best efforts, the prosecution inexorably began to build its case.

The stage was being set for Conley. When the sweeper took his place in the witness box, he was clean-shaven and impressive in a new suit. In what would be a fourth version of his story—one fortified by facts he’d failed to include in any of his affidavits—he smoothly delivered his tale:

“Mr. Frank was standing up at the top of the steps and shivering and trembling and rubbing his hands. . . . He had a little piece of rope in his hands—a long, wide piece of cord. His eyes were large and they looked right funny….His face was red….He asked me: ‘Did you see that little girl who passed here just a while ago?’

“I told him I saw one come along there and she come back again, and then I saw another one come along there and she hasn’t come back down….He says: ‘Well, that one you say didn’t come back down, she came into my office….and I went back there to see if the little girl’s work had come, and I wanted to be with the little girl, and she refused me, and I struck her, and I guess I struck her too hard, and she fell and hit her head against something, and I don’t know how bad she got hurt. Of course you know I ain’t built like other men.’

“The reason he said that was, I had seen him in a position I haven’t seen any other man that has got children. I have seen him in the office two or three times before Thanksgiving and a lady was in his office, and she was sitting down in a chair and she had her clothes up to here, and he was down on his knees….”

In the Victorian moral climate of Atlanta—where the sanctity of southern womanhood was as revered as Jesus Christ—Conley’s assertion was staggering. The courtroom was deadly quiet as the witness finished his account with a flourish, describing how he had taken Mary Phagan’s body to the basement in the elevator and then returned to Frank’s office to write the murder notes.

It took Conley just four hours to tell his story; Luther Rosser, generally regarded as the best cross-examiner in the South, would spend sixteen trying to break it.

Rosser started Conley out with a few friendly inquiries. Then he directed him to the topic of Frank’s alleged affairs.

“When was the first time you watched for Mr. Frank? Who was with him?”

“That lady that was with Mr. Frank the [first] time I watched for him sometime last July was Miss Daisy Hopkins [an Atlanta prostitute].”

Rosser encouraged Conley to continue, and the witness produced an impressive list of Frank’s seductions leading up to Mary Phagan. Often, Conley claimed faulty memory and refused to answer a question, but he did so in such an offhand way as to seem ingenuous rather than duplicitous. For nearly three days, Rosser grilled his witness, and by the end of it he’d not only failed to discredit Conley but he’d allowed him to introduce a mass of evidence incriminating Frank in numerous liaisons.

Realizing their mistake, Rosser and Arnold attempted to have the new evidence concerning Frank’s sexual habits struck from the record. They were overruled, and the courtroom burst into applause.

Impressive as Conley had been, he did let slip one very peculiar item. Almost as an afterthought, he admitted that on the morning of Mary Phagan’s death he’d defecated in the factory elevator shaft. The defense must have failed to see what this admission suggested. It would be much later before Frank’s advocates understood the significance of what would come to be known as “the shit in the shaft.”

Had not Conley been such a crippling witness, it’s doubtful that Rosser and Arnold would have elected to follow the risky tactic of introducing Leo Frank’s character as the foundation of its case—a move that would later allow the prosecution to produce witnesses to discredit the factory superintendent’s good name.

Frank was delivering his autobiography, a document that, like the man who wrote it, was meticulous, rational, pinched.

In all, the defense called more than two hundred character witnesses, many of whom were young girls who worked in the factory. Lost in the ceaseless shuffle of faces and voices was a shy teenage boy who spoke so softly that the court reporter could barely comprehend his testimony. This was Alonzo Mann. After managing to get out that he’d never seen Frank bring women into the office for immoral purposes, Mann was excused from the stand.

The last and most dramatic piece in the defense’s argument was Leo Frank’s own statement. At 2:00 P.M, on the first day of the fourth week of the trial, Frank started reading from a lengthy manuscript:

“In the year 1884, on the 17th day of April, I was born in Paris, Texas. At the age of three months, my parents took me to Brooklyn, New York, and I remained in my home until I came South, to Atlanta, to make my home here.”

Frank was delivering his autobiography, a document that, like the man who wrote it, was meticulous, rational, pinched. It led him from his marriage day to the morning of Mary Phagan’s death, and then, in painstaking detail, through the trials and infamies he’d endured since his arrest. Finally, when Frank addressed Jim Conley’s testimony, he grew impassioned. First, he said that it was he who had informed the police that Conley could write—not the act of a guilty man. Then he added:

“Gentlemen, I know nothing whatever of the death of little Mary Phagan. I had no part in causing her death nor do I know how she came to her death after she took her money and left my office. . . .

“The statement of Conley is a tissue of lies from first to last….The story as to women coming into the factory with me for immoral purposes is a base lie, and the few occasions that he claims to have seen me in indecent positions with women is a lie so vile that I have no language with which to fitly denounce it….

“Gentlemen, some newspaper men have called me the Silent Man in the Tower, and I have kept my silence advisedly, until the proper time and place. The time is now. The place is here. And I have told you the truth—the whole truth.”

It was prosecutor Hugh Dorsey, though, who would have the last word. Dorsey began by introducing a string of witnesses to rebut those who had attested to Frank’s good character. Then he started his summation. The attorney wove a hypnotic plea for Frank’s conviction. He contended that the murder notes had definitely originated in the mind of a white man because everyone knew that blacks didn’t use the words “did” and “Negro”—they used “done” and “nigger.” He pointed out numerous holes in Frank’s statement—chiefly the accused’s inability to ever really produce a satisfactory explanation for his twitchy behavior on the day of the murder and the morning after. Near the end of his argument, Dorsey lingered on the diction of the letter Frank had written his uncle that fateful Saturday: “‘It is too short a time since you left for anything startling to have developed down here,’” Dorsey read. “A sentence pregnant with significance, which [bore] the earmarks of the guilty conscience….‘Too short a time’….that itself shows that the dastardly deed was done in an incredibly short time.”

On Saturday, August 23—nearly a month after the trial had begun—Dorsey was ready to stop. But judge Leonard Roan was fearful that if the jury returned a verdict on the weekend—when the city was crowded with country people—a riot might commence. Roan called both sets of attorneys to the bench and, in a discussion audible to the jury, decided to postpone the end of the trial until Monday. To the jurors, this conversation must have suggested that if Frank were acquitted they could be the objects of violence.

On Monday morning, August 25, the trial was concluded. The jury retired, and Frank was taken to the Tower, where Judge Roan had decided for safety reasons that Frank should remain during the verdict—a clear denial of a defendant’s constitutional right to be present in the courtroom to hear the findings of the court.

After only four hours of deliberation, the jury returned with its verdict: “Guilty.” Immediately, such a din broke forth in the courtroom that Judge Roan was barely able to poll the jurors. A friend rushed to Frank’s cell with the bad news. Frank again declared his innocence. Lucille started sobbing. Then she fainted.

Outside in the streets there was bedlam. Thousands of jubilant Georgians jostled to get near city hall. Hugh Dorsey was hoisted on the crowd’s shoulders and cheered. Soon there appeared on the city hall steps an Appalachian musician named Fiddlin’ John Carson. After raising his Stradivarius to his shoulder, Carson started singing:

Little Mary Phagan

She went to town one day;

She went to the pencil factory

To get her weekly pay.

She left her home at eleven,

She kissed her mother goodbye;

Not one time did that poor girl think

She was going off to die.

Leo Frank he met her

With a brutish heart and grin;

He says to little Mary,

You’ll never see home again . . .

Judge Roan passed the sentence,

He passed it very well;

The Christian doers of heaven

Sent Leo Frank to hell.

The next day, in a secret meeting attended by Frank, his attorneys, and the prosecutors, Judge Roan condemned Frank to hang by his neck until he was dead.

It took Leo Frank nearly two years to exhaust the appellate procedures available to him. The first hurdle was a request for a new trial, which Judge Roan denied. Afterward the judge made a curious statement: “With all the thought Judge Leonard Roan I have put on this case, I am not thoroughly convinced that Frank is guilty or innocent. The jury was convinced….I feel it is my duty that the motion for a new trial be overruled.” Roan would not be the only judge to express uncertainties. In his minority opinion on the Frank case, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes expressed his belief that the atmosphere outside the city hall’s courtroom led to Frank’s conviction. “We think the presumption overwhelming that the jury responded to the passions of the mob,” Holmes declared.

During the long months of legal maneuvering, a number of the prosecution’s principal participants began coming forward with doubts of their own. The most startling of these changelings was William Smith, Jim Conley’s attorney. Smith had performed a brilliant job of protecting Conley’s rights. He had not only warded off a grand jury attempt to indict Conley along with Frank, but he had arranged for Conley to be charged with a misdemeanor offense, which carried only a one-year sentence. Yet certain aspects of Conley’s story began to gnaw at Smith. He carefully examined the trial transcript, focusing on Conley’s testimony about the notes. Eventually, Smith arrived at several disturbing insights. First, he concluded that the author of the murder notes was someone fond of placing three adjectives—“long, tall, black”—in front of his nouns. In his testimony, Conley had often used such a construction. Second, and quite contrary to Hugh Dorsey’s closing argument, he discovered that Conley frequently used the words “did” and “Negro” while on the stand. Finally, Smith attacked the murder-note phrase “play like the night witch did it.” Among the voodoo folk faiths believed in by many southern blacks was one concerning a spirit called “the night witch,” who was thought to strangle children in the dead of night. As far as Smith could determine, Frank—a smug New Yorker relatively new to the South— could not possibly have heard of the night witch. Conley, however, would have known all about her.

In October 1914 Smith went to the Atlanta newspapers with his story: Conley had composed the murder notes; Conley had murdered Mary Phagan. Shortly thereafter, Smith conveyed his newfound belief in his client’s guilt to the governor.

By the summer of 1915, however, Leo Frank was beyond the help of a mere governor. He was living in limbo on the prison farm in Milledgeville, where he’d been transferred from the Tower in the dead of a June night.

John Slaton, however, was more interested in several other aspects of Conley’s testimony. The governor had come into possession of a number of love letters Conley had written to his girlfriend, Annie Maude Carter. The letters were rife with Conley’s sexual fantasies, which were very much like the obsessions he attributed to Frank. It occurred to Slaton that by an act of transference, Conley had actually ascribed his own lusts to Frank.

But of even greater concern to the governor was the “shit in the shaft.” Slaton concluded that the dung that had been crushed in the elevator shaft on the Sunday following the murder was a crucial piece of evidence. If, as he testified, Conley had transported Mary Phagan’s body to the basement in the elevator, the excrement would have been mashed on Saturday. Why was it still fresh on Sunday morning? To Slaton, the answer was obvious: Conley never set foot in the elevator with Mary Phagan’s body. His mendacity on this one point suggested to Slaton that Conley’s entire testimony was a lie, and though the governor was acutely aware of the public sentiment against Frank, he decided to commute the condemned man’s sentence.

By the summer of 1915, however, Leo Frank was beyond the help of a mere governor. He was living in limbo on the prison farm in Milledgeville, where he’d been transferred from the Tower in the dead of a June night. In the gnatty torpor of the long Georgia afternoons, as sweat beaded on his brow and his throat wound oozed, Frank dispatched scores of cool, almost triumphant-sounding letters to correspondents all over the country. He was convinced he would one day be cleared. But in the desperately cheerful notes Frank received from the two people closest to him—his wife and his mother—there was a mounting apprehension. “It has poured all day, and I hope that the same weather prevailed in Atlanta. I had a kind o’ idea that the ruff nex might erupt tonight when they should be filled with booze and the spirit of independence,” Lucille wrote in a July note mailed from a relative’s home in the college town of Athens. And on August 14—in a letter primarily given over to family news—Leo Frank’s mother expressed her horror at the virulent writings of Tom Watson. Surely, she prayed, the man wasn’t as dangerous as he seemed. Watson, however, was a greater threat to Rhea Frank’s son than she could ever have known. It was because of Watson that Frank would be dead in three days.

One of the most charismatic figures in southern history, Tom Watson had appointed himself to act out the hatreds and confusions of Georgians in the post-Reconstruction era. Early in his career he was an eloquent spokesman for disenfranchised white and black southerners alike. He was elected to Congress as a Democrat from Georgia’s Tenth District, and then he ran for the vice-presidency with William Jennings Bryan on the Populist party ticket in 1896. But after Bryan’s defeat, Watson grew bitter and began railing against greedy Catholics and Jews as well as the blacks he’d once championed. The vehicles for his diatribes were The Jeffersonian and Watson’s Magazine.

Hardly a week went by during the latter part of 1914 and the early months of 1915 in which Watson didn’t attack “the Jew.” Early on, he was content to write, “Frank belonged to the Jewish aristocracy and it was determined by the rich Jews that no aristocrat of their race should die for the death of a working class Gentile.” Later he grew bolder, analyzing Frank’s facial structure and seeing in it the markings of a child-killer. Finally, in early August 1915, the editor declared: “THE NEXT JEW WHO DOES WHAT FRANK DID IS GOING TO GET EXACTLY THE SAME THING WE GIVE NEGRO RAPISTS.”

On August 17, Leo Frank became the first Jew to get what southern firebrands gave Negro rapists.

Articles about the lynching of Leo Frank dominated the Atlanta newspapers for three or four days following the event, but then all interest in the story seemed to cease. There were no serious investigations into the composition of the lynch party. There were no meaningful postmortems on the saga. The process of repression had begun.

The legacies left by the Frank case, though, made themselves apparent almost immediately. During the hysteria surrounding the lynching, the Ku Klux Klan—an organization whose original fraternal incarnation had all but petered out by 1915—held its first cross burning atop Atlanta’s Stone Mountain, thus reinvigorating itself for a new life. Almost simultaneously, the Anti-Defamation League was organized in New York City.

The Frank story’s most profound ramifications, however, were visited directly upon those most intimately involved.

To the victors went the spoils:

Hugh Dorsey was elected governor of Georgia; he eventually took a superior court judgeship in Atlanta.

Tom Watson was elected to the United States Senate in 1920. Two years later he died in office. At his funeral the most ostentatious floral arrangement was a cross of roses eight feet high sent by the Klan.

The members of the lynch party lived out their lives in relative comfort. “Yes, Frank was lynched by this town’s best people,” said a man who shall here be known as Willis Blackburn. It was a fall day nearly seventy years after Frank’s death, and Blackburn—a well-educated Marietta native—sat in an office in the heart of town. “The children of some of these people work right here in the building,” he said. Then, in a barely audible tone, he uttered the name Herbert Clay. Clay, long dead, was solicitor general of the Blue Ridge Circuit (which included Marietta) and the son of Alexander Stephens Clay, one of Georgia’s Reconstruction-period U.S. senators. According to Blackburn and long-standing speculation, Clay conceived, planned, and led the lynch party. Blackburn said Clay and his comrades were unblemished by the lynching. Yet he refused to elaborate. “I have spoken too much,” he said through tight lips.

To the defeated went troubles and obscurity:

William Smith, the attorney who changed his mind about Conley, moved to Charleston, South Carolina, where he worked as a longshoreman. After nearly a decade on the docks, he resurfaced in New York City and organized a maritime law practice.

Governor John Slaton traveled the world for five years, fearful of returning to Georgia. At the conclusion of World War I, he finally came home to Atlanta to practice law. He died in 1955.

Luther Rosser and Reuben Arnold continued successful law practices in Atlanta, but their reputations were badly damaged. The lawyers had based their case on the calculation that no southern jury would convict a white man on the testimony of a black (Rosser’s courtroom statements about Conley were the most bigoted utterances made during the case). They failed to comprehend why a northern Jew would excite the animosity of poor gentile Georgians. In A Little Girl Is Dead, the most widely available book on the Frank case, Harry Golden cites an essay written on Frank by the pastor of Mary Phagan’s church: “When the police arrested a Jew, and a Yankee Jew at that, all of the inborn prejudice against the Jews rose up in a feeling of satisfaction, that here would be a victim worthy to pay for the crime.”

After burying her husband in Brooklyn, Lucille Frank returned to Atlanta, where she took a job at one of the city’s best fashion salons. She lived out her widowhood in the Howell House apartments on Peachtree Street until her death in 1957.

In the aftermath of Frank’s lynching—as during the trial—the most mysterious character remained Jim Conley. After serving his year in prison, Conley returned to Atlanta, where he is said to have been killed in a knife fight in 1962. Harry Golden wrote that Conley confessed to Mary Phagan’s murder on his deathbed, but this appears to be wishful thinking. Over the last few years legal aides have rifled through microfilm files in libraries across the South searching for news of Conley’s confession. They have found nothing.

These were the ghosts who accompanied Alonzo Mann into the Georgia capitol press room on December 22, 1983. But the Board of Pardons and Paroles was impervious to the importuning of the dead. Its spokesman stood before a microphone and announced:

“Assuming the statements made by Mr. Mann as to what he saw that day are true, they only prove conclusively that the elevator was not used to transport the body of Mary Phagan to the basement.

“For the board to grant such a pardon [a full exoneration], the innocence of the subject must be shown conclusively. This has not been shown. Therefore, the board hereby denies the application for a posthumous pardon for Leo M. Frank.”

When the board’s representative sat down, reporters surrounded Alonzo Mann. After stifling a sob, Mann offered his only reaction: “It just isn’t Christian.”

Why did the board—a body composed of one black and four white southerners— reject the pardon application? One afternoon several months following the decision, Michael Wing, the board’s chairman, sat at his desk in a building across from the capitol. “The testimony of Mann sounded good,” he said. “It matched up with the shit in the shaft to suggest that Conley was the killer. But does his testimony alone provide sufficient reason to overturn the findings of the court? I wouldn’t convict someone seventy years after the fact solely on the testimony of an eighty-year-old man, so how can I pardon someone on that testimony? To get that pardon, they needed to prove that Frank was innocent beyond a shadow of a doubt, and Mann’s testimony just didn’t do that.”

The demanding criteria the board set was really the least of the problems facing the attorneys who filed the pardon request. From the outset, the board had decided that it would not be influenced by a number of key factors in the Frank case. Frank’s lynching was regarded as immaterial, for it had no bearing on his guilt or innocence. The standards of the court in 1915 were regarded as immaterial, since nearly any turn-of-the-century trial could be overthrown in the 1980s if present-day standards were applied (thus the police department’s questionable method of extracting Conley’s confession, the courtroom discussions that may have prejudiced the jury, and Frank’s absence at the reading of the verdict weren’t even considered). On top of that, the crowds outside the temporary courtroom and the possibility that anti-Semitism was a factor in the case were also regarded as immaterial.

In essence, the board had only been concerned with Mann’s new evidence. In its handling of the pardon application, the board subjected Frank’s advocates to both a biting irony and an uncanny restaging of the events of seventy years earlier. The irony: in 1913, when Frank needed to be tried on only the facts, his case was surely affected by atmospherics; in 1983, when Frank needed the mood prevalent at his trial introduced into the proceedings, he was judged on just the facts. The element of déjà vu: black and white gentile southerners had once again banded together to find against an outsider, a Jew.

It was Christmas 1984, and Alonzo Mann, in failing health, had moved from his mobile home in Virginia to the United States Veterans Hospital in Mountain View, Tennessee—a vast complex of red-brick institutional buildings tucked into a high valley. On a bitterly cold morning he sat on an old red vinyl chair in a dormitory common room. He wore pants hitched up high around his waist, and rubber bands held his shirt cuffs to his feeble wrists. On the other side of the room, two overly effusive Baptist matrons were leading a chorus of the maimed—some men were legless, others had holes in their necks, most were simply numbed and distracted—through a series of Christmas carols. As the sad, soft voices came together in the refrain of “O Little Town of Bethlehem, ” Mann turned up his hearing aid and said, “I’ve given my prayers, and I’m ready to die now. I’ve lived a long life. My only regret is that I didn’t say what I had to say at the right time. You know, you think entirely different when you’re fourteen. And out in front of the courthouse, there were hundreds of people. Some of ’em had sticks, and one of ’em had an ax. But I do wish I had said something. I have thought about this thousands of times since then. I have thought of it when I went home and sat down. I have thought of it when I got up and had breakfast. I am thinking about it now.”

For a moment Mann listened to the choir, but then he said, “I did tell a few other people back then, but I was just a boy, a shy boy. Nobody believed the things I said. But I know what I know. I know why he had the girl, too. He wanted her money. [Frank’s defenders have long contended this was Conley’s motive.] He’d wanted to borrow money from me earlier in the day.” Mann stared down at his folded, wrinkled hands. “I didn’t realize Mr. Frank was in deep trouble. Even after the sentence, my father said, ‘They won’t keep him. He’ll get out.’ But it didn’t work that way.

“I didn’t dream this. I can see Jim Conley as plain as day with that girl, and my age doesn’t have a thing to do with it. The only thing I’ve ever dreamed about this case is of Mr. Frank hanging from a tree. That dream has haunted me.”

“I was all tore up. Frank was good to me. I did things for him. If he wanted something from town, I’d go get it. I had a little desk over in the corner in the same room. They said in the paper Frank had beer bottles in there, but that was a lie.” The thought of alcohol brought Conley back to Mann’s mind. “Jim Conley was a smart nigrah. He could talk to you, and he had a personality you would like. But he drank all the time. And he had women in there. He was drinking that morning.”

In response to the allegation that his age made him an unreliable source of information on the Frank case, Mann bristled. “I didn’t dream this. I can see Jim Conley as plain as day with that girl, and my age doesn’t have a thing to do with it. The only thing I’ve ever dreamed about this case is of Mr. Frank hanging from a tree. That dream has haunted me.”

“Silent Night” was now wafting across the room. Soon Mann would return to his bed in the drab communal quarters. His prized possessions were a certificate signed by Lester Maddox making him an honorary officer in the Georgia State Troopers, a photograph of him with “Little Johnny—the ‘Call for Philip Morris’ Cigarette Boy” at a restaurant he once managed, and a story about what he saw one morning in a pencil factory. Three months later, Mann was dead of heart disease and pneumonia. His story was all that he left.

For more, read Oney’s prize-winning book, And the Dead Shall Rise: The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank.

[Photo Credit: Public Domain c/o Wikimedia Commons]