The majority of New York City’s 44,000 licensed taxicab drivers are amateurs. They are men who smoke cheap cigars, support in-laws, write novels, handicap horses, buy wheat futures, educate children and spit out windows with far more aplomb than they drive cabs. They know only that after a 10-hour day they can earn between $15 and $25, that the Police Department requires “optional” dress—plaid shirts, hand-painted collie-dog ties and windbreakers—and that they must bring their own dashboard mementoes from home.

Amid all this amateurism, however, there are five durable professionals who have driven a total of 5.5 million miles in New York City traffic for a collective 222 years. All of the five men wince as they remember streets so narrow that cars had to pass hubcap to hubcap. They remember waiting behind pushcarts, horse-drawn wagons, stalled trucks and old electrics in need of a charge. They remember sitting in traffic tie-ups for so long that passengers would pass out from the noxious gas fumes of the day. They all remember so clearly that they agree: everything is better today—including the traffic.

The heartiest of the five is Daniel McCarty, an unabashed lover of the city who has been driving for 52 years, beginning with a 1910 hand-crank magneto-starting Cadillac in 1914. McCarty, who is still driving at 72, started before the city had traffic lights and when the Saint Patrick’s Day marchers paraded from Washington Square to the Road House Inn, at 110th Street and Lenox Avenue.

“When I started driving,” McCarty said, “the speed limit was 15 miles an hour and you had to obey.

The majority of New York City’s 44,000 licensed taxicab drivers are amateurs. They are men who smoke cheap cigars, support in-laws, write novels, handicap horses, buy wheat futures, educate children and spit out windows with far more aplomb than they drive cabs.

“On lower Broadway we used to have a bicycle cop called ‘Speedy Delaney’ who’d wait for you and if he spotted that you were going over the limit, even if it was 18 miles an hour, he’d start pedaling like the wind until he caught you. You could see him bouncing up and down on the cobblestones, blowing on his whistle. He was a sight.”

There was very little hailing of taxis around 1914, according to McCarty. Most of the trade was from strategically located taxi stands which had regular customers. The rate was 50 cents for the first mile and 40 cents for each additional mile and it was too steep for most New Yorkers. At the time McCarty was partial to Prospect Place, which was then around 42nd Street and the East River, where Tudor City and the United Nations are today.

“It was a lovely spot then,” McCarty said. “There were a few brownstones with wealthy people who would take cabs and it was on a high bluff so I could watch the boats come up the river between fares.”

Taxi-stand life was rugged, according to McCarty, and “line crashers” were beaten, had potatoes jammed up their exhaust pipes and their tires slashed. It was a matter of getting on a line, and if any other driver objected, being able to adjudicate the matter as simply as possible.

“Mister McCarty’s always been a little pugnacious himself,” McCarty said, by way of explaining how he managed to remain on the most sought-after hack stands of the day. They included Reiscnweber’s, at 58th Street and Eighth Avenue; Churchill’s, at 49th Street and Broadway, and Bustanoby’s, 60th Street and Columbus Avenue. McCarty used his Cadillac until 1916, when he started driving a maroon Sharon. He sold the Cadillac for five dollars (“the acquisition of a lot of money never troubled me”).

Today McCarty no longer works the stands.

Nowadays I keep on the move. It doesn’t pay to sit still. Today you’ve got to be on the move all the time. I keep going. I move mostly through midtown, going real slow, keeping an eye forwards and backwards for fares. It’s a kind of mental telepathy you get. You really get it. I can tell by just looking at the way a man walks, or a lady moves. I just get the feeling whether they want a cab or not.”

Julius Salit is 64 years old and has been noisily driving a taxicab since 1922.

He pulled his taxi along the curb at 23rd Street and Eighth Avenue, directly under a “No Parking” sign, slammed his door shut, jammed a cigar between his teeth, and started across the street as though enraged.

“I’ll tell ya. You wanna know what? You wanna know? I’ll tell ya. My first call was from the Dollar Line piers at Atlantic Avenue, Brooklyn. Boy, do I know Brooklyn. It was the summer, 1922, like yesterday, a call all the way to the Hotel Seville, 28th Street and Madison Avenue.” He is grinning and his voice carries. He seems to create his own audience.

“How much? I don’t remember. A couple of dollars. You know that all the luxury piers used to be over here downtown in Chelsea. Did you know that? That all the fancy, boats used to come in south of 21st Street? We used to line up to get them. You could always make a little on the trunks.”

Salit winks. He nudges. He has a confidant, an accomplice.

“Nineteen years I worked Brooklyn. I knew how to play it. I’d spot one-way work. You know from Brooklyn they can take you further and further out until you’re in Montauk and you have to come all the way back empty—unless you know where to go. I knew where to go.

“Do you know I was past commander of the New York Taxi Post of the American Legion? I could tell you a lot.”

Salit’s attention was directed to another driver standing at the curb. He had his hand out with his palm up and yelled, “Him! That guy! He’s been around a Iong time too. I’ve seen him too.”

Traffic, according to Salit, is better today than it was 30 years ago, except that he has a plan which would make city driving a “thriving pleasure.”

“The trouble is the law. They’ve got no teeth in them. What they should do is make every fourth street an express street cross town and localize it in the afternoon for deliveries. That way you wouldn’t get bottle necks.” Before he could explain “localize” Salit saw a woman walking toward his parked cab.

“See ya,” he said.

“You’ve got to remember that most side streets in those days were two-way and so narrow that you’d have to watch your hubcaps when you passed another car.”

Louis Abrams watched Salit go. He seemed relieved. Abrams, who has been driving 42 years, likes taxicabs. He has a brown 1924 snapshot of himself behind the wheel of his first taxi.

Abrams said he agreed with Salit that traffic is better today than at any time in the last 40 years.

“You’ve got to remember that most side streets in those days were two-way and so narrow that you’d have to watch your hubcaps when you passed another car. And there were no avenues like you have today either. You didn’t even have Seventh Avenue South until the early Twenties and—I know you look at it now and it’s hard to believe—but it just wasn’t there until after they put in the subway and that didn’t open until 1917.

“And Sixth Avenue,” Abrams smiled, giving a nod to the heavens and pressing out the front of his sweat-er with the palms of his hands.

“Sixth Avenue used to stop dead in the Village. Flat dead it would just stop. And you’ve got to remember there were elevated lines on Sixth Avenue as well as Third Avenue and Second Avenue and Ninth Avenue and all those el pillars and all the trolley cars underneath and the chain-drive trucks breaking their linkage and horse-drawn wagons and electrics that needed a charge and the smells and fumes and everything. Let me say, it’s been a long time since I’ve had a passenger pass out from the traffic.”

“It was not until after World War I that various companies started designing and introducing taxicabs,” Abrams said.

“About 1924 the Shaw—we used to call them ‘Baby Shaws,’ because they were so neat and compact—came along. They were great cabs. We also had the Willys Knight Landolet. It was like an early hansom with the convertible top for the passengers and when the top was closed it only had a little peek-a-boo window and the fellows used to call them ‘Boudoir cabs.’

“For two years, from 1924 to 1926, even Harry C. Stiitz—you’ve heard of him—made a small cab that was a beauty, but about then out came the Luxor Cab Company’s Luxor, which was simply magnificent. It was real luxury. It had a copper radiator grill which. we kept polished, and real leather seats, and the interior upholstery went right up to the roof. The Luxor, was the Rolls Royce of taxicabs, except for one cab called the Paramount, which was even better, but no one remembers it.”

Outside the Belmore Cafeteria—Park Avenue South and 28th Street—any time of day or night, the city’s taxicab drivers gather. Benny Rubinstein, who has been a driver 42 years, eats at the Belmore every day and he likes to listen to the brasher stories of some of his friends.

It is for Rubinstein a world in which advantage is often taken by someone else. He was pleased when they removed the taxi meters from behind the driver’s seat.”

“Good thing they took them out,” Rubinstein said. “We used to get a lot of phony law suits every time we stopped a little short—people’d yell that they hit their heads on the meter.”

Rubinstein also disagrees with the general notion among drivers that their jobs take them out from under the eyes of bosses and supervisors.

“Taxicab drivers have more bosses than anyone else,” Rubinstein said. “We got bosses all over. The meter is our boss. The police are our bosses. The passengers—if we’ve got any—they’re our bosses. The taxi owners have their own inspectors—they’re not our bosses? And at the garage—there is no boss? Listen, taxi drivers have nothing if they don t have bosses,”

Emmanuel Goodman holds his key up to the sun.

“You see this? I own my own. In 1924 I bought a 12-cylinder Packard funeral car which had been converted. It had isinglass windows and a hack bureau medallion which in those days cost me five dollars,”

In March of 1937 the city stopped issuing taxi medallions. Today there are 11,772 “frozen” medallions estimated to be worth about $27,000 apiece.

“In 1924 when I got my medallion, they were still open,” Goodman said. ‘‘All you had to do was go over to the Hack Bureau—they used to be at S7th Street— pay $5 fur a medallion, go out and get a car-for $40 and you were in business. But what was the sense of it? What was the sense of buying a fleet of medallions in those days? All you’d have, believe me, was a fleet of losing propositions.”

“Ah, no. You can keep the old days.”

Goodman pinched a dime between his fingers.

“You see this, right here, the dime? Well, you wouldn’t have it in the old days to go buy yourself a corned beef sandwich. We were like chauffeurs. We had to wear hats with badges, and he had buttons on our jackets and a hack license on a tag through our lapels like we were some luggage—we shouldn’t get lost.

“Ah, no. You can keep the old days. Today, come the winter, my wife and myself, we get in the cab and we go to Miami.

Goodman looked across the street at the Belmore.

“You see those guys? They can walk into a restaurant and buy a sandwich. So what, it costs a dollar. You’ve got a dollar. That’s what’s important. When I started, a fleet driver hacking on a day-line who made $5 in a day was considered a master. Most of the time you’d wait and wait and wait and when you got a fare and when you saw a quarter tip, you saw a King.

“Even your customers have it better off today. Today your car has windows that roll up, a heater, a smooth ride. You should have seen some of those old locomotives like the Vogel. Your fares froze to death and at the end of the day you were stiff from driving. You were stiff and you were a young man.”

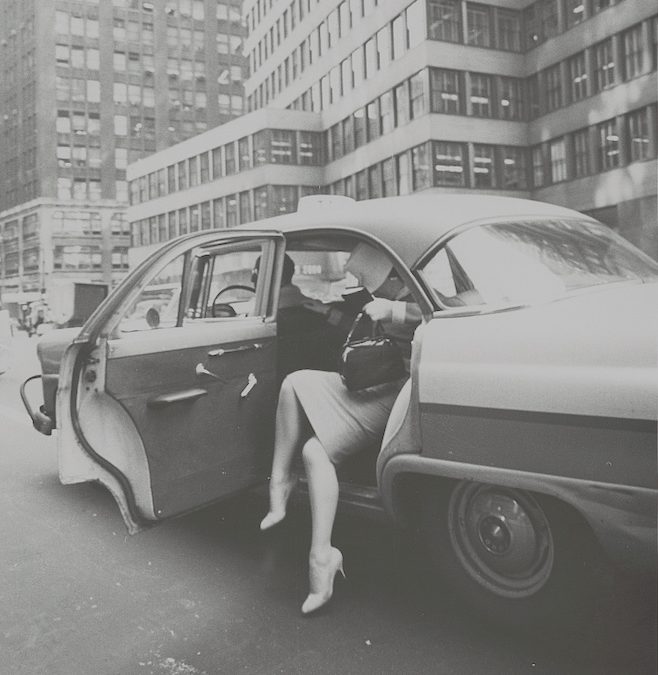

[Photo Credit: Angelo Rizzuto via: The Library of Congress]