THE COACH—Why should I win? Why should I feel fine tonight? Why should my friends and the ones who think they’re my friends stand out there pretending to wait for the traffic to thin when they’re really waiting to pump my hand because it says 65 under Home and 60 under Visitors?

THE GOLFING PARTNER—Two years ago our foursome had to start changing partners every six holes. It was just getting too damn competitive and we didn’t want to damage any friendships. The coach was as bad as any of us. Guys jingling coins in their pockets when another fellow was about to swing, or dropping a club when the fellow was about to putt. So now we just switch and play for fun because you don’t want to be screwing up somebody that’s going to be your partner in a few more holes, do you?

THE COACH—Why should the other coach go home in a trance tonight because he lost? Why should the unit of measurement in sports be wins and losses instead of floor burns or execution or honest exhaustion?

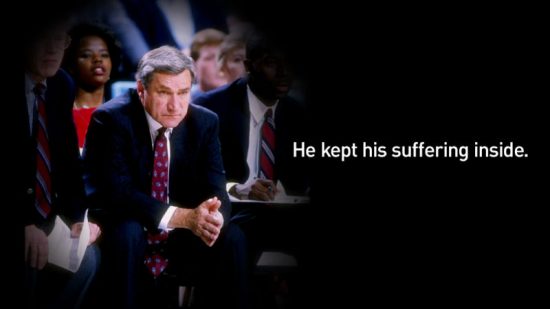

THE FRIEND—The coach had been taking those Gelusils, those antacid things. Every once in a while you’d see it cross his face, but he’d never let you know his stomach was bothering him. Then that morning of the NCAA Eastern Regional final in 1969, he woke up and his gut was killing him. The players never knew a thing.

THE DOCTOR—I took him to the hospital that morning. We thought it might be an ulcer, but the tests didn’t show anything. It was gastritis.

THE COACH—I think it was from eating Italian food. I don’t think it was nerves.

THE DAUGHTER—Daddy always kept his suffering inside.

THE COACH—Shouldn’t I be more upset when we play poorly and win than when we play well and lose? No matter how much I tell our players that, there’s the people on the streets….

THE SPORTS PSYCHOLOGIST—Competition, once it reaches a certain level, is symbolically destroying the other person. It’s even in the verbs used in sports: blew away, crushed, destroyed. The person who is really sensitive to this has a conflict within himself. Coaches go through many moral conflicts that people never know about. What makes it even more difficult on them—aside from the chronic pressure—is that they can’t address all their problems directly. They’re at the mercy of their players. Just watch them long enough and you’ll see how their anxieties from these conflicts come out.

THE DAUGHTER—I remember after we lost to Virginia last year and daddy said, “The starving people in India don’t care.” But I could tell how upset he was. He tries to make conversation so nobody will be uncomfortable, but he doesn’t want to talk. You’ll ask him something and he won’t hear you. I remember once after a loss there were friends at the house and he sat there staring at the stat sheet for half an hour, like he was in a trance.

THE SPORTS PSYCHOLOGIST—We all have defense mechanisms to handle these kinds of anxieties, things we’ll do unconsciously. There’s nothing wrong with defense mechanisms in themselves—they are fundamental to the maintenance of mental health. For example, you might convert a side of you that you feel is animalistic into an outlet of a higher order, like philosophy or academics or art. Whether the defense mechanism is considered bad or honorable depends on the society and environment it occurs in.

Some people who have lived in tiny Chapel Hill more than a decade remember having seen him in its stores or on its streets maybe twice.

THE WRITER—Everybody does it different, you see. Elimination is Bobby Knight’s way. The anxiety eats and eats and then, just when it is about to take all of him, he lashes at whatever’s standing in front of him and then he’s safe again. Could be a Puerto Rican cop during the Pan Am Games, could be a fan at the Final Four. Everybody does it different, it’s just that some of the ways are more constructive than others. John Wooden had that rolled-up program, that symbolic club, in his fist. Rather than beat up anybody, he’d tap it into his other palm. Al McGuire would get off a good line and then hop a motorcycle and leave it all back there with the exhaust. Old Phog Allen would drink constantly from a milk bottle full of water. Everybody does it different, you see.

The theologian was talking about a college basketball coach, one of the winningest in the country. “There are tremors in Dean Smith,” said Sam Hill, a friend who once taught at the University of North Carolina. “I wish there was a psychic seismograph placed in the middle of the man’s core. There’s great stirring there.

“No, we never really talked about that. The significant interaction we did have was extremely rare but extremely self-satisfying. But he always seemed to control the conversation, either by deflecting what you wanted to talk about or by picking your brain. It was not for nefarious reasons. I’m not sure he has any close friends. He’s probably a shy man. There was always something a little bit uncomfortable about talking with the man.”

The man lives on five rolling acres at the end of a dead-end road surrounded by a sentinel of trees. Some people who have lived in tiny Chapel Hill more than a decade remember having seen him in its stores or on its streets maybe twice.

The man once devoured the works of theologians Soren Kierkegaard and Paul Tillich deep in the night; now he is more likely to feed the Betamax a 1 a.m. basketball tape. He spends his few leisure hours playing with the one-and three-year-old children from his second marriage, golfing, listening to jazz or sampling fine restaurants at tables tucked in corners. His friends include a psychiatrist, who is also his wife; another psychiatrist he golfs with, and the chancellor of the university. He invokes powerful trust in those who know him well and often the opposite in those who don’t. He insisted that his three older children go away for high school or college to escape the long shadow in a short town and find their own identities. All three turn to him first with a problem.

His teams are 20-game winners before they unsnap their warmups. They have won 25 or more games nine times, third only to Wooden’s 11 and Adolph Rupp’s 10. They have either won the regular-season title (nine times) or finished second (six times) every year from 1967 to 1981, a marathon difficult to fathom across the minefield of the ACC. They have reached the Final Four six times, second only to Wooden-coached teams. He has, beyond that, coached the U.S. Olympic team to the 1976 gold medal.

And yet: Dean Smith has never won an NCAA championship.

The paradoxes are strewn across the last 25 years of the man’s life, since it was wrenched out of the fundamental Baptist farm dirt of Kansas and asked to grow in the wind-swept sand of big-time college basketball. They are layered in ever-tightening circles, from the dichotomy of the coaching record to the stirrings of the psychic core.

He is a man whose perfect hair and continual coat and tie and constant “we do things the right way here” reminders leave the long-range looker with the image of a moonlighting guest host from the 700 Club. And yet, he opposes the Moral Majority.

He is a man who sometimes knocks down a cold beer for thirst and two Scotches for relaxation after a game, but wouldn’t let former Tar Heel broadcaster Bill Currie bring his then 16-year-old son to Smith’s hotel room if Smith had ordered a drink.

A man utterly anchored to the image of the university… and yet, within three weeks in 1977, one opposing player was claiming Smith had pushed him in the hallway at halftime and another that Smith had cursed him on the court.

A man whose rigidity hatches teams that talk alike and look alike and sprint to midcourt at every 4 p.m. shriek of his practice whistle alike. And yet, whose freedom of thought innovated the four-corner offense, the free-throw huddle, the run-and-jump attack defense, the crosscourt pass once considered heresy against a zone and the ingenious use of last-minute timeouts that once eliminated an eight-point deficit in 17 seconds.

He will explain only the paradoxes near the crust. “Years ago,” he said, “Dr. Seymour [his church’s pastor] gave a sermon that made so much sense to me. It was called The Paradox of Discipline, and I had it mimeographed. He made the point that the disciplined person is the one that’s truly free. The student who says, ‘I could make A’s if I tried,’ but who doesn’t have the discipline to sit down and do it, is the one who’s shackled. The disciplined student is free: He has the choice of making an A or D.”

Sam Hill: “You’d know him and enjoy him more if he let more of his imperfections out.”

Does that explain the office desk and car seats that are a tempest of pink telephone message slips, scribbled notes, game tapes, spent shells of his three-pack-a-day habit, coffee cups, newspaper clippings and magazines? That mess is one of his few visible membership cards with Club Human. Very few see the mess.

The rest get the outside of the blue Cadillac. They get the handshake, the astonishing memory of their names, the elocution never hitched by ums, uhs, wells, and never—watch, he’ll make a point of it—never an obscenity.

“He could go to the grocery store without a tie on,” laughed Linnea, his wife. But he wears responsibility like that tie, wrapped tight and double-knotted around the neck, and it gets so stifling that he can’t.

“I’d say his flaw is that he gets caught up sometimes in the masculine image of being the supplier of everyone’s needs, the one in control of every situation,” said the 37-year-old Linnea. “One of his old friends who’d read the book on Dean that’s out said to me, ‘What’s it like living with God?’ The thing that’s missing [from portrayals of Smith] is the vulnerability. He has affectional needs. He is very sensitive and sentimental, and he can express deep emotions intimately even better than I. He sends certain flowers for certain occasions and remembers so many little events in our relationship that it got to the point we were celebrating too many things.”

Sam Hill: “You’d know him and enjoy him more if he let more of his imperfections out.”

He finds no practical reason to do this. No one is invited to put his ear to the rumble of rearrangement deep below, to the gut drives and intellectual conclusions grating at each other in the core. The rumble has retreated deeper and deeper as he has learned, without realizing it, how to nudge it along. His midnight-to-2 a.m. theological reading and raking of the 1960s and 1970s have subsided. He has found answers he is not anxious to rip open the ribs on again, and when he is pressed he can deliver them smooth and pat, without a signal of the anguish it took to find them.

His whole life now seems a steady handshake between the two warriors within him, and at 51 he is happy with the truce. When he shanks a tee shot, he neither spits out the whole word in deference to one nor swallows it in deference to the other. Dean Smith, according to a friend, quietly says the letters “F-u.”

The basketball game has just become a storm and the storm is making the people crazy. Sam Perkins is swatting away a Ralph Sampson shot and Ralph is retrieving and leaping to dunk and the ball is clanging off the rim and jumping at the lights and the wire lines running from the backboard to the ceiling are twanging like he’s strummed them and now Ralph is retrieving that miss, too, and coiling to dunk again and the bodies crush and the whistle blows and the ref points to a Carolina kid and the crowd….

Oh no. Not that chant. Not here, on the court with the pale blue outline of of North Carolina in the middle.

Dean Smith stops twirling his arms for a traveling call he never gets and gropes the scorer’s table for the public-address microphone. He finds a mike and speaks. No sound. Wrong mike. The crowd at the end where Sampson will shoot free throws begins waving its arms to distract him. The chant grows louder. Smith clutches another mike. No sound again. He gropes a third time and finds the right one.

“No obscenities,” he commands. “And none of this [he waves his arms). Let’s do this the right way.”

The chanting and waving cease and the scolding draws an ovation.

Time out. The Carolina subs stand in unison and applaud the starters. Smith pinches up both thighs of his blue-gray flare pants and squats facing the bench. One assistant squats on his right, one on his left. All three were math majors. The subs form a tight leaning half-circle behind Smith’s back, the five starters sit silent in seats in front of him, the managers complete the circle standing behind the bench. Smith’s hands waggle but he never yells or goes red in the face. The timeout ends, the managers rush to towel off the seats before somebody’s flare pants get splotched by somebody’s cheek sweat. Smith rakes a loose strand of hair into place. The starters return to the court, cool as the coach.

When napalm was black-gashing Vietnam, Smith rose once more, signing an antiwar petition and standing on the post office steps for prayer vigils in protest.

His five players become five fingers of one fist and are tightening it around the opponent’s one-finger offense. They are nudging balls free and skidding across the varnish after them, and when they finally take the lead Dean Smith’s go-ahead hand clap is no more boisterous than his pregame-intra hand clap.

The Heels win by five and Smith shakes the other coach’s hand with his right hand while buttoning his blue-gray sportcoat with his left.

In the summer of 1959, a black student of theology stepped from the of back of a bus into the glare of Chapel Hill. He had come to spend the summer on the staff of Binkley Baptist Church, and he would do just fine in this quiet, tight town as long as he kept his eyes screwed to its sidewalks and its books.

Dr. Robert Seymour, the pastor, had larger ideas. He took aside Dean Smith, assistant UNC coach at the time and a teacher in Binkley’s adult Sunday school class. “I told Dean that if he came with us to a restaurant, I was almost certain the black student would be served,” said Dr. Seymour. “He was eager to do it.”

The three of them picked their place, inhaled deeply and placed their orders. That Dean Smith out there? You shuh? Then you’re damn right ah ’m gonna serve the nigrah.

Years later, Smith would ignore an alumnus’ threat that it would cost the school $1 million in endowments if the coach made Charlie Scott the first black scholarship athlete in UNC history. He would refuse to join the Chapel Hill Country Club until it eliminated racial discrimination.

When napalm was black-gashing Vietnam, Smith rose once more, signing an antiwar petition and standing on the post office steps for prayer vigils in protest. “I got some letters on that,” he said. “I’m not a pacifist, but it couldn’t be called a just war. Like El Salvador—what’s going on down there?”

In the early 1960s he insisted that everyone traveling with the team attend church on Sundays. In the early 1970s he contributed to George McGovern’s presidential campaign.

“Liberal?” echoed former broadcaster Currie. “He hates Jesse Helms like the devil hates holy water.”

I remember daddy and my brother playing tennis and basketball and he’d always beat Scotty. Scotty would get mad and throw his racket down. Daddy would not bend to Scotty. And I remember daddy always winning when our family played Monopoly. He’d get mad if Aunt Joan sold a property cheap to me—he’d say she was only doing it because I was her niece. He wanted everybody going all out, forget who your relations are.

After a while, our goal wasn’t Monopoly. It was to beat him.”

You see, the other coaches are all getting wild-eyed and sandpaper throat and hair sweat-pasted to their foreheads, and Dean’s standing over there like the pastor just said “Please rise.” ’Course, he’s busy ripping the weakest ref on the floor to black-and-white ribbons, but half the time he’s doing it while he’s clapping so nobody in the seats will notice.

Then he’ll come out of the locker room when he’s won and tell everyone his team isn’t that great when he knows he’s up to his French cuffs in cats that will be driving Benzes somewhere in two years. Then the writers will go running to their machines writing what a genius he is for winning with no 20-point scorers.

“A lot of coaches want to beat him so bad they get paranoid,” said Tates Locke, former Clemson coach. “They get their kids so high they can’t play a lick. The man owns the league. He puts a lot of pressure on officials and gets a lot of good calls. He beats everyone like a drum and they get jealous. Then they sit around and talk about him. Coaches are like damn women in a sewing circle.”

Dean Smith does not make himself or his relentless basketball machine the issue when it is time to recruit.

Ex-Duke coach Bill Foster: “I thought Naismith invented basketball, not Dean Smith.”

Tates Locke: “There’s one coach in this league who sits at the foot of the cross.”

Virginia coach Terry Holland: “There is a gap between the man and the image the man tries to project.”

UNC assistant coach Eddie Fogler: “If I were an outsider, I’d probably think something was phony here, too.”

It is bad enough getting beaten two or three times every year by the same man, but it is maddening when the man doesn’t cheat, curse, scream and often does not even check into the same hotel as the rest of you at the annual ACC coaches’ convention.

“I think he’s starting to make a little more effort to be one of the guys,” said Holland. “There was a lot of animosity before and he felt bad. He was antagonizing people and he didn’t know why.”

An example came in 1981, when it appeared Virginia’s Jeff Lamp would make the all-ACC team over one of Smith’s players. “It must be terribly embarrassing for Jeff when Terry pulls him out for defensive purposes,” said Smith, smiling innocently.

All they really want the man to do is come down and confess he’s as consumed with winning as they. But no. The only thing anymore that kicks open the man’s furnace door is loyalty. Loyalty transcends even image and self-control. Loyalty triggered his anger at former player Dennis Wuycik one night in a Mexican restaurant, Wuycik having written in his bi-weekly Poop Sheet that ex-UNC assistant John Lotz was on the verge of getting fired as Florida head coach two years ago. “How could you say that about someone else from our program?” fumed Smith, even though he knew the item was common knowledge.

Loyalty spurred the two incidents in 1977, when he screamed at Virginia’s Marc Iavaroni and Kentucky’s Rick Robey for roughing his guards. Iavaroni said Smith pushed him in the hallway at halftime; Robey said Smith called him a sonuvabitch.

“Maybe someone in the stands called Robey a name and he thought it was me,” suggested Smith, who also denies pushing Iavaroni.

Holland, five years after the Iavaroni incident: “In this particular case, Dean Smith was very wrong. There seemed to be no apology forthcoming, like he was right and our player was wrong. If Dean thinks he’s at the point where he’s right all the time, and the people of North Carolina don’t even question him, then that’s wrong. The point I was trying to make was, I don’t think he needs to be afraid of being a human being. The man’s achievements are incredible. That should not preclude making errors. Sure, I’d feel more comfortable if he’d admit his competitiveness to me. But he has no reason to.”

Dean Smith does not make himself or his relentless basketball machine the issue when it is time to recruit. Dean Smith sells the university’s nationally acclaimed academic environment. Dean Smith reminds you that 115 of his 121 lettermen have degrees and lists all of them, including former equipment managers, their degrees and their current occupations, in the back of the team brochure. Dean Smith’s workdays get longer and longer with each graduating class because he is still sending letters to the last sub and his parents from his 1960s teams. Dean Smith still sends a yearly Christmas card, brochure and personal invitation to visit to the house painter who encouraged Wuycik to attend UNC in 1968.

Everybody does it different, you see. Only, who else seals it off with such honor?

Mitch Kupchak remembers the hand on his shoulder. It was 8:30 on a winter morning his junior year, and a doctor bent over him to perform an epidural block on his back. The Tar Heels had returned from a night road game just 5½ hours earlier, but there in a surgical mask and gown, touching him through the pain and fear, was Dean Smith.

He demands his players spill their egos into his cupped hands and four years later he can almost guarantee them 100 victories, the discipline and atmosphere to earn a diploma, and a friend for life. Interviewing them, the new ones or old ones, is collecting obituary quotes in the present tense.

Sophomore Matt Doherty: “I honestly don’t believe coach Smith ever does anything wrong.”

Walter Davis: “Coach Smith is a saint.”

Kupchak: “If coach Smith pointed me to a cliff and told me to close my eyes and jump, I wouldn’t question it.”

Chorus: “We’ve never even heard coach Smith say a curse word.”

One former player lacerates the reverence and Dean Smith loves him, too. “Hey, El Deano, how the hell ya doin’?” greets Doug Moe, now coach of the Denver Nuggets.

“I’ve kidded him that he’s got to relax and let it out—I know he wants to,” said Moe. “Sure, he does sometimes. A lot of people don’t think he’s normal but it’s difficult to show your personality when you’re held in such esteem. He’s in that atmosphere all the time and he’s a workaholic. Yeah, I saw part of that game against Virginia. Give Smitty a message for me. Tell him I said, ‘Bullshit.’ ”

Smith once stayed up all night helping Moe study for a math exam that Moe registered a 15 on. Moe then flunked out of UNC, was selling insurance in nearby Durham and was finished forever as an X on Smith’s chalkboard, when he received a phone call. “Dean said I had an appointment at Elon College with the coach and president at 2 p.m., to wear a sportcoat, and be on time,” said Moe, “and then he hung up. After I graduated from Elon, he got me on a team playing in Italy, then got me into the ABA. If it wasn’t for him, I’d never have gone back to school, never played pro basketball, never become a coach.”

Fortified by his record and that kind of big-name testimony, Smith is in a position to recruit players for their grace as human beings as well as athletes. He once told a high school senior named Sampson that he could help the Carolina program, but that it would win without him. His players know that no 17-year-old legend will be promised their starting jobs.

His program’s caste system is based on seniority, not points. Each year, Smith picks a senior to sell to the media, starting off postgame press conferences with unasked-for monologues on that player’s boxing-out skills after the player has shot 1-for-9. Last year Sam Perkins walked away from the ACC tournament with the MVP trophy in one hand and, since he was a freshman, the team’s film projector in another.

The UNC stat sheet lists players alphabetically, not in order of points-a-game as at other schools, and omits minutes-played. Only Phil Ford has averaged 20 points for a season on a UNC team since 1970. Smith sets the tone by flying economy class while his players fly first class.

The selflessness is bored in from the beginning. Matt Doherty, as levelheaded as 20-year-olds come, walked into Smith’s office as a freshman last year wearing a McDonald’s All-American jersey. “That would be a nice shirt for your brother to wear,” Smith said.

His accent is still as Kansas flat as the day 24 years ago he brought it south. From behind a door, you picture vocal chords tautened all the way back to the sinuses and then twanging the words through the nostrils. When he is angry, the voice shafts right through you.

“When I first went to North Carolina, Frank McGuire was head coach,” said Larry Brown, now New Jersey Net coach. “He’d call you a sonuvabitch and you’d laugh. I thought my name was Jew Bastard for two years. But coach Smith could say, ‘Darn it, you messed up,’ and it killed you.

“I’m still very much a part of the human race, and no matter how much we talk to the team and staff about this, you still keep score and winning is important. In my mind, though, I’ve adjusted my thinking and the conflict isn’t that great anymore.”

“He’s developed this ‘we’ thing and it’s one of the reasons he dislikes interviews about himself. It would destroy the ‘we’ thing if he became too big.”

The “we” thing coaxes players into passing up the free 10-footer for the teammate’s five-footer. It is laced so tightly that when Walter Davis cried as fluid was drained from his finger before an ACC tourney game, his teammates cried, too. But some wonder if the emphasis snuffs the spark of spontaneous individual genius that can steal NCAA championships.

“At North Carolina the open guy takes the shot even if he’s not hot,” said Charlie Scott. “Mike O’Koren got hot at one point against Marquette in the 1977 title game and then stopped shooting. Against Indiana in the final last year, they’re giving the ball to Isiah Thomas every time and we should’ve gone to AI Wood. But I love coach Smith. You wouldn’t want him to change.”

“Did he look at his wristwatch when you talked to him?” —A former UNC assistant

2:30—SECRETARY: Coach Smith will see you in his office now.

COACH SMITH: Nice to see you. That appointment you have with my son Scott has been canceled. It’s important that he not grow up just being associated with me or Carolina basketball.

WRITER: Oh.

2:35—WRITER: What troubles you about big-time college basketball?

COACH SMITH: Our society puts too much emphasis on the success ethic, which I don’t have that much time to get into (glancing at wristwatch) with you. (Coach Smith elaborates on basketball program.)

2:40—WRITER: You run such a tightly disciplined program, many people would wonder why you don’t seem to apply the same strict discipline to yourself.

COACH SMITH (glancing at watch): I could lose 10 pounds which I’ve done, which I will do, in fact I just did in the fall. No. I’ve never really tried to quit smoking, but I don’t think that has anything to do with your story about our basketball program.

2:45—WRITER: How would you spend a free day, if you didn’t have to be anywhere at any certain time?

COACH SMITH: It depends what I’d done the day before, but I don’t see how that question has anything to do with anything.

2:47—WRITER: Does the lack of free time, the constant intrusion on your privacy, ever wear you down?

COACH SMITH: I can handle that. People just have to understand. The player in school is our No. 1 priority here. If one of them needed to see me right now, I’d excuse you even if you were the governor. You’ve got to establish priorities. That’s why I’ve only got a half hour (glancing at watch) to do this interview. (Coach Smith elaborates on basketball program.)

2:52—WRITER: Maintaining the proper image is obviously very important to you, but many people feel that you take it too far, that they’re never getting spontaneous feelings from you.

COACH SMITH: I’ve never understood that. If I told you, ‘I don’t like doing this with you and I wish I hadn’t asked you in here,’ and hurt your feelings, would that be better than being polite and saying, ‘Nice to see you’? I say what I believe; just not everything I believe. I’m not after people liking me. I’m after my players and friends and me liking me. You can’t educate the world.

2:56—WRITER: What did you feel a few years ago, when Terry Holland said there was a gap between the image of Dean Smith and the man?

COACH SMITH (glancing at watch): Terry Holland doesn’t know me. I’m not even sure what the man said.

2:58—WRITER: You have been quoted as saying a chapter titled “The Power of Helplessness” in a book by Catherine Marshall was a turning point in your life.

COACH SMITH (glancing at watch): I don’t want to get into preaching what’s important in my life.

WRITER: But what impact did “The Power of Helplessness” have…?

COACH SMITH (standing up): I believe our time is through. It’s 3 o’clock.

WRITER: I’ll need more time than this. Can we get together again?

COACH SMITH: Let’s finish it over the telephone. Call me at 10 o’clock tomorrow night.

3:01—Writer walks out, knowing all about helplessness, but wondering where the hell the power comes in.

Some men get deposited all at once, like silt from a flash flood. And some grow in thin and fine layers, sifted and spread by the river of time. In Kansas the land is flat and the rivers crawl and the sediment lays itself slow.

Fifty miles from the terrors of Topeka, 77 from the wonders of Wichita is where Dean Smith grew up. In a small town named Emporia, hemmed by a horizon of wheat and corn, where the only reason to look up was God and grain elevators, where the only sin a man could find was in his mind.

Lord, Iemme get a hit. I’m not asking for a homer or even a double. Just a single, Lord, just a nice clean single. Just Iemme get a single, Lord, and I’ll promise to… to… to become a medical missionary.

Dean Smith remembers blurting that prayer in eighth grade, then lashing the hit and being walloped by guilt. Competition was the only thing capable of reaching up from his gut and manipulating his mind. The only mischief his parents remember him getting into was stealing a watermelon from a field with four other boys. Otherwise it was straight A’s and glee club and four hours of church every Sunday.

Right and wrong were a thousand fallow acres apart. Education was a commandment. His mother and father, both strict Baptists, had master’s degrees and were teachers. Vesta was the disciplinarian, the organizer, the worshiper of detail, the woman whose arid air of self-control gave her classrooms the silence of a benediction. “I expected the children to do what was expected” is how she summarized her approach. She subdivided her two children’s 15-cent weekly allowances thusly: a nickel for the church collection, a nickel to save, a nickel to spend. “Never any liquor in the house,” said Joan, three years older than Dean. “Never any tobacco. We never even visited a person who took a drink. Dean and I still won’t take one in front of mom or dad.”

The father, Alfred, was one of the first coaches in Kansas to integrate a junior high team and the first in eastern Kansas to integrate a high school team. On road trips, if a restaurant owner refused to serve all his players, he marched all of them out.

In a world such as this, competition produced life’s only uncertainty. It was the only intoxicant, the only patch of gray between the black and the white. When Joan had completed junior high with just two B’s among her A’s, Alfred offered Dean the monstrous sum of $100 if he could match it. He did. When Dean was eight and they played Ping-Pong in the basement, Alfred would make mistakes on purpose when he reached 19 points to teach the boy how to function under pressure and never to give in. Several years later, Dean was state table-tennis champion in his age bracket.

Dean assumed the pressure positions naturally in sports: quarterback in football, catcher in baseball, point guard in basketball. The only time trouble trespassed during his first 25 years, he responded with more self-control than even his mother. “One of his friends got sick one day and was dead of lumbar polio within three days,” recalled Joan. “My mother and father and I were all immobilized with grief. Dean never cried. He got out all the news clippings he’d saved that mentioned his friend’s achievements in sports, then sat on the porch pasting them into a scrapbook that he presented to the boy’s parents.”

He attended the University of Kansas on an academic scholarship, was a substitute on a team that won the 1952 national championship under Phog Allen, then joined the Air Force and coached a service team in Germany. Bob Spear, who met him there, invited him to be his assistant at the Air Force Academy.

Spear recommended him to North Carolina coach Frank McGuire and in 1958 he became a 27-year-old UNC assistant. What McGuire remembers most is the intensity of Smith’s competitive burn: Smith smearing himself on the walls of the handball court when he played the far more experienced McGuire. Smith, out of shape and puffing desperately, beating All-American York Larese in a game of one-on-one. Smith leaning over McGuire’s bed in a New York hotel room one night, in a sleepwalking defensive crouch. “I woke up and there he was,” McGuire said. “Scared the hell out of me.”

McGuire jumped to the pros in 1961 and talked the chancellor into hiring Smith, but left behind a program on NCAA probation for recruiting violations. Smith’s recruiting was restricted, the schedule was cut back and the team went 8-9, 15-6 and 12-12 his first three years. In the aftermath of McGuire’s alligator shoes, 18 pinky rings and 1957 national championship, the midwestern Baptist seemed a dull denouement. Defeat ate the young coach from the inside and never bored its way out. After losses, he would isolate himself in the front of the bus and sometimes barely speak for days.

Criticism festered. His children took abuse in school. “The student newspaper,” said Billy Cunningham, the star of that era, “was vicious.” It all burst on a January night in 1965, when a mob of angry students stood waiting for the team bus to return from a 107-85 devastation at Wake Forest. As the mob chanted abuse at him, Smith’s eyes shifted. There, dangling from an oak tree, was an effigy of himself. A student lit a match and the effigy went up in flames. Cunningham stomped to the tree and ripped the dummy down. Smith went home thunderstruck.

Now came the first trial of a soul that still had the world sorted in its old neat Kansas compartments. And from the ashes beneath the oak tree, like curled smoke, rose questions. Were sports worth this? Should he continue devoting his life to this? How different was the fire inside him from he fire he had witnessed?

At this point, his sister sent him Catherine Marshall’s book on religious philosophy, Beyond Our Selves. His mind riveted to Chapter 10, “The Power of Helplessness,” which emphasized that crisis can become the moment of creative strength if it forces us to admit our insufficiency and dependency upon the grace of God. He read a procession of theologians and began tapping at the concrete of his fundamentalist background.

“Through my readings, I put my vocation in perspective,” said Smith. He’s talking about himself now so the whole face and shoulders have tightened and the hand that doesn’t have the cigarette gestures rapidly as he talks. “I realized that neither the emptiness of defeat nor the ecstasy of winning were all of life. I realized maybe I wasn’t made out to coach. Maybe I could do something for others. I began not to have to take it so seriously.”

Two days after his effigy hung charred from the tree, his team extinguished Duke and students asked him to speak at a pep rally. “I can’t,” said Dean Smith. “The rope’s too tight around my neck.”

His marriage to Ann, the mother of his three older children, began souring in the years after Smith watched himself burn on the oak tree. In his few pinched free hours, they didn’t enjoy talking about or doing the same things. He moved out, moved back, moved out. Divorce didn’t come until five years after the first separation.

“The guilt was incredible,” said his sister Joan. “You stay married, no matter what, the way we were brought up. That ordeal made him search himself even more.”

“Several years after the divorce,” said daughter Sandy, “we talked about it and it was the one time I saw him cry. He felt so guilty because he thought he had messed up our family.”

And in the soul, tremors that began the night of the effigy and rippled straight through the divorce, two evolutions occurred. One, of course, was his basketball philosophy. “He was always interested in you as more than a basketball player,” said Donnie Walsh, a player Smith’s first year as head coach and later an assistant at UNC. “But as the years went by, he began emphasizing that even more.”

The other was his theology. “Christianity,” Smith believes now, “is an amoral religion based on the fact that we are loved—not on keeping rules. We respond in ethical action out of gratitude for this love.”

“He began applying the theology he was developing to basketball,” said Joan. “ ‘You are no more special because you are Phil Ford or Walter Davis than the last player on the team. You do not have to score any certain number of points, just as in Christianity you do not have to keep any special rules to win God’s love. You are accepted. I value you.’

“The teacher-learner role that he began emphasizing more gave meaning to his profession. It’s why he’s still a college coach.”

Dean Smith: “It is still my job to have players be the best they can be—if you’re going to do something, you ought to do it well. But I’m probably looser during games now. I’ve lost that ‘we-got-to-win’ thing. I’m still very much a part of the human race, and no matter how much we talk to the team and staff about this, you still keep score and winning is important. In my mind, though, I’ve adjusted my thinking and the conflict isn’t that great anymore.”

Funny, the times the man and his second wife play doubles and he keeps whizzing shots at the weaker partner on the other team until his wife shoots him a look and says, “C’mon, Dean, we’re here to relax… remember?”

These days, the Smiths don’t care to play doubles all that much.

[Photo Credit: AB; image by Jim Cooke]