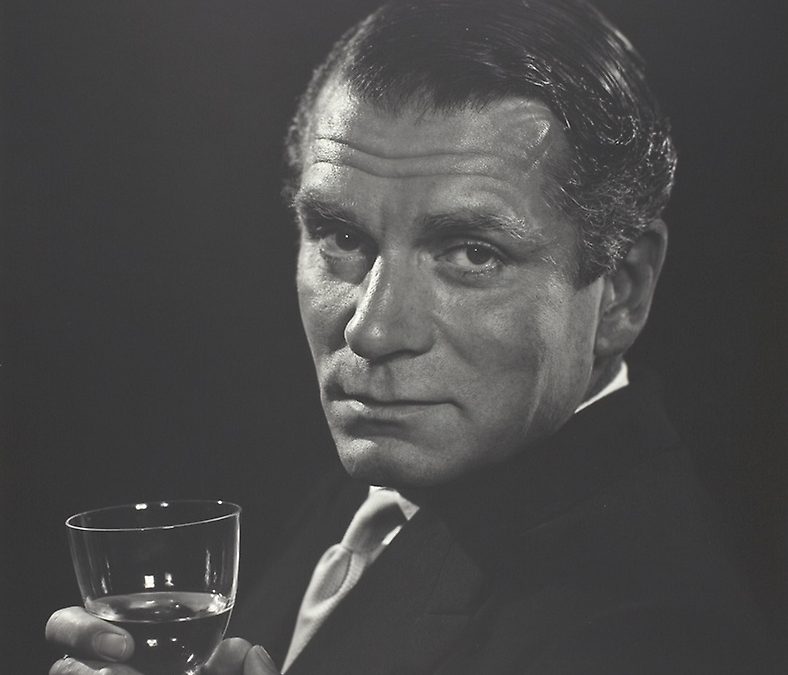

An old man died in his sleep one day last week, and it was as if a continent had sunk into the sea. A wave of feeling rose and moved outward, and when it was gone the world seemed different and smaller than it had been before. Laurence Olivier was dead. Hamlet was dead. Heathcliff, Othello, Oedipus, Richard III and Archie Rice were dead. Something in human experience was dead that had been alive because of him, and all who knew and loved his work were pervaded by a sense that something priceless had left us forever.

Olivier’s daughter-in-law Shelly described his final hours, on July 11 in Steyning, West Sussex. “It was the most beautiful way for Laurence to go. He was absolutely at peace. All his family were with him, and he was at home in England. I think he knew this is where he wanted to die. It was just natural causes and a gradual weakening. Laurence was his usual spirited self and was very dignified before he went.” He was 82.

There was a warm outpouring of encomiums. Michael Caine called him “unique and undeniably irreplaceable,” and Anthony Quayle said his death marked “the closing of a very great book.” Others spoke of his creative daring, his volcanic energy, his shimmering magnetism, his incomparable technique, his astounding versatility. “Olivier played men who were handsome, nasty, noble, wily, treacherous, sleazy, awesome, whining, crippled and mean,” wrote Megan Rosenfeld in the Washington Post. “He played fops, kings, soldiers, gods and lovers, and, once or twice, women. But he never lost his dignity—unless it was deliberate.” Anthony Hopkins summed up: “He was the greatest actor of the century.” And Peter Hall went even further: “He was perhaps the greatest man of the theater ever.”

“The only time I ever feel alive,” he once confessed, “is when I’m acting. If I stopped acting, I’d cut my throat. I have to act to breathe.”

Eloquent reviews of Olivier’s work were quoted in obituaries. “He is a comedian by instinct,” critic James Agate once wrote, “and a tragedian by art.” Olivier played Richard III, wrote biographer John Cottrell, as a reptile: “Hard, thin lips, lank, jet-black hair, stalactitic nose; a skulking, smarmy-voiced, sardonic villain with scuttlingly spider-like walk and a deformed, two-fingered hand that someone likened to a shrunken haggis.” Kenneth Tynan said his Titus Andronicus resounded with “great cries … the noise made in its last extremity by the cornered human soul.” And John Mason Brown described Olivier’s 1946 Oedipus as “one of those performances in which blood and electricity are somehow mixed. It pulls lightning down from the sky.”

What manner of man perpetrated these astonishing achievements? A man of genius, obviously, but a genius crisscrossed with contradictions. “He was a lion,” says Richard Attenborough. “His extraordinary courage enabled him to defeat illnesses which would have killed off the rest of us 20 years ago.” But at the same time he was quiveringly timid. He dreaded fans and on occasion suffered paralyzing stage fright. With colleagues he could be magically charming—and brutally blunt. When Dustin Hoffman, a dedicated Method actor, stayed awake for two nights preparing to look tired in a scene, Olivier observed dryly, “You should learn to act, dear boy. Then you wouldn’t have to put yourself through this sort of thing.” When he needed it, the man could assume what one reporter called “a surfeit of dignity,” but hidden, behind the pompous persona was a giant ganglion of anxiety. “The only time I ever feel alive,” he once confessed, “is when I’m acting. If I stopped acting, I’d cut my throat. I have to act to breathe.”

Olivier acquired his anxieties growing up in a domestic tragicomedy. His father was an impoverished Anglican clergyman with “a storming, raging tornado” of a temper, his mother a warmhearted, frolicsome hausfrau who did hilarious imitations. Life was a drama of contrasts, and little Larry tuned in on the soap opera. At five he converted his nursery into a theater and presented his own playlets. At 10, he played Brutus in a choir-school production of Julius Caesar, and Dame Ellen Terry, who happened to attend, pronounced him “already a great actor.” At 12, Olivier lost his mother, who died of a brain tumor, and was sent away to a dreary public school, where he translated his anomie into imaginary lives. In a school production of Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew, the 14-year-old Olivier played Kate, as a “bold, black-eyed hussy,” wrote one dazzled reviewer. A year later he strung himself with green electric lights and pranced about as a battery-operated Puck.

Burning to set the Thames on fire, Larry enrolled in a London drama school, but at 17 he bore small resemblance to the future matinee idol. With a thicket of coarse black hair and huge black eyebrows that met in the middle and hung like an awning over both his eyes, he looked more like Caliban than Hamlet. A barber took care of the cosmetic problems, and talent did the rest. After a stint with the Birmingham Repertory, Larry at 23 was cast as the odd man out in the world premiere of Noel Coward’s Private Lives. Career safely launched, he married a wellborn belle of the theater named Jill Esmond—who bore him one son, Tarquin, 52—and in 1933 Larry signed on to play Greta Garbo’s lover in Queen Christina. But Garbo dumped him in favor of John Gilbert, and Olivier slunk away in humiliation.

Five years later, after a series of major classical roles (Romeo, Mercutio, Hamlet, Macbeth, Iago), he let Hollywood coax him back to play Heathcliflf in Wuthering Heights. Savage, tender and smolderingly handsome, he gave one of the great romantic performances in film history and overnight became an international megastar. Screaming fans mobbed him and tried to tear his clothes off. Nominated for an Oscar, he lost out to Robert (Goodbye, Mr. Chips) Donat, but as Maxim de Winter in Rebecca and as Darcy in Pride and Prejudice, Olivier soon had the ladies swooning again.

Among them was an exquisite young thing named Vivien Leigh, the actress-wife of a wealthy British barrister, whose “wondrous, unimagined beauty” had Olivier swooning too. Fire over England, the costume epic that brought them together, ignited a passion that blazed out of control. Risking a scandal, Leigh bolted to L. A. to be with her lover—and advertise her availability for the part of Scarlett O’Hara. Vivien won the role of the century—and got her man to boot. After a double divorce, the two married in 1940, and for the next 20 years they loved like maniacs, fought like tigers and worked like demons—most memorably as co-stars in the Old Vic’s twin productions of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra and Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra.

While a lieutenant in the Royal Naval Voluntary Reserve during World War II, Olivier was permitted to film Henry V, the first and finest of four movies he adapted from Shakespearean dramas. Released in 1946, the film revolutionized the historical genre and was instantly acclaimed as the most brilliant costume epic ever produced. Olivier played the king as a fiery young dynast, and in his first effort as a director he demonstrated a talent for cinema so vigorous that critic James Agee called the film “one of the great experiences in the history of motion pictures.”

Olivier’s film of Hamlet (1948) took some guff for its textual liberties and for the Freudian gloss on the relationship between the hero and his mother. Critics also pointed out that Olivier’s bold style tended to bulldoze the subtleties out of the sensitive, introspective prince, and Olivier privately agreed. Nevertheless, the film is intelligent, by far the best movie of Hamlet ever made. It won four Oscars, including one for Best Picture and one for Olivier as Best Actor. Richard III (1956) was no less skillful. “Olivier plays his Richard for laughs,” wrote reviewer Alan Brien, “and he raises the grisly humors of the horror comic to the level of genius.”

On the other hand, Othello (1966), a film shot directly from a controversial stage production, displays Olivier at his worst: tricky, cold, trussed in technique and addicted to gestures. “What he gives us,” wrote Jonathan Miller, “is a Notting Hill Gate Negro—a law student from Ghana—made up of all the ludicrous, liberal cliché attitudes toward Negroes: marvelous sense of rhythm, wonderful way of walking, etc. Shakespeare’s Othello was a Moor, an Arab, and to emphasize his being black in this way makes nonsense of the play.”

The problems he encountered directing The Prince and the Showgirl (1957) can hardly be blamed on his lordship. (The youngest of his profession to be knighted—he was 40—Olivier in 1970 became the first actor to be elevated to the British peerage.) He made the movie just for the money, and he was working with an impossible prima donna: Marilyn Monroe. Always late, never prepared, she drove her punctual, disciplined director and co-star out of his balding gourd. One day he exploded: “Why can’t you get here on time, for f—’s sake?!” he demanded. “Oh,” she replied ditsily, “do you have that word in England too?”

Olivier by now, alas, was having more serious woman trouble. Leigh had developed a case of tuberculosis. (It would cause her death in 1967.) On top of that, she was caught up in a cycle of manic depression that made her dangerous to herself and to her husband. They began to have violent fights. One night, after she attacked him while he was sleeping, he flung her across the room and she struck her forehead on a nightstand. That did it. Olivier moved out.

In 1960, shortly after their divorce became final, he married Joan Plowright, a warm, steady, down-to-earth actress and homebody who gave him three children (Richard, 27, Tamsin, 26, and Julie-Kate, 22) and the eye of calm he needed. “I know of nothing more beautiful,” he said, “than to set off from home and to look back and see your young held to a window and being made to wave at you. It’s better than poetry, better than genius, better than money.”

Money was urgently needed, however, to provide for the children’s future, and as founding director of the National Theatre Olivier’s salary was minimal. So in the last two decades of his life he made a lot of trashy movies—The Jazz Singer and Inchon were among the worst—just to beef up his bank account. Sometimes he worked when he was ill. Olivier won a major bout with cancer, but since 1974 he had been fighting off a muscle-withering disease called dermatomyositis. By last week he could fight no longer.

After life’s fitful fever, may he sleep well.

[Photo Credit: Yousef Karsh c/o The Art Institute of Chicago]