“Down in Los Angeles,” says Garry Schumacher, who was a New York baseball writer for thirty years and is now assistant to Horace Stoneham, president of the San Francisco Giants, “they think Duke Snider is the best center fielder the Dodgers ever had. They forget Pete Reiser. The Yankees think Mickey Mantle is something new. They forget Reiser, too.”

Maybe Pete Reiser was the purest ballplayer of all time. I don’t know. There is no exact way of measuring such a thing, but when a man of incomparable skills, with full knowledge of what he is doing, destroys those skills and puts his life on the line in the pursuit of his endeavor as no other man in his game ever has, perhaps he is the truest of them all.

“Is Pete Reiser there?” I said on the phone.

This was last season, in Kokomo. Kokomo has a population of about fifty thousand and a ball club, now affiliated with Los Angeles and called the Dodgers, in the Class D Midwest League. Class D is the bottom of the barrel of organized baseball, and this was the second season that Pete Reiser had managed Kokomo.

“He’s not here right now,” the woman’s voice on the phone said. “The team played a double-header yesterday in Dubuque, and they didn’t get in on the bus until four thirty this morning. Pete just got up a few minutes ago and he had to go to the doctor’s.”

“Oh?” I said. “What has he done now?”

In two and a half years in the minors, three seasons of Army ball, and ten years in the majors, Pete Reiser was carried off the field eleven times. Nine times he regained consciousness either in the clubhouse or in the hospital. He broke a bone in his right elbow, throwing. He broke both ankles, tore a cartilage in his left knee, ripped the muscles in his left leg, sliding. Seven times he crashed into outfield walls, dislocating his left shoulder, breaking his right collarbone, and, five times, ending up in an unconscious heap on the ground. Twice he was beaned, and the few who remember still wonder today how great he might have been.

“Young man,” he said, “you’re the greatest young ballplayer I’ve ever seen, but there is one thing you must remember. Now that you’re a professional ballplayer you’re in show business.”

“I didn’t see the old-timers,” Bob Cooke, who is sports editor of the New York Herald Tribune, was saying recently, “but Pete Reiser was the best ballplayer I ever saw.”

“We don’t know what’s wrong with him,” the woman’s voice on the phone said now. “He has a pain in his chest and he feels tired all the time, so we sent him to the doctor. There’s a game tonight, so he’ll be at the ball park about five o’clock.”

Pete Reiser is thirty-nine years old now. The Cardinals signed him out of the St. Louis Municipal League when he was fifteen. For two years, because he was so young, he chauffeured for Charley Barrett, who was scouting the Midwest. They had a Cardinal uniform in the car for Pete, and he used to work out with the Class C and D clubs, and one day Branch Rickey, who was general manager of the Cardinals then, called Pete into his office in Sportsman’s Park.

“Young man,” he said, “you’re the greatest young ballplayer I’ve ever seen, but there is one thing you must remember. Now that you’re a professional ballplayer you’re in show business. You will perform on the biggest stage in the world, the baseball diamond. Like the actors on Broadway, you’ll be expected to put on a great performance every day, no matter how you feel, no matter whether it’s too hot or too cold. Never forget that.”

Rickey didn’t know it at the time, but this was like telling Horatius that, as a professional soldier, he’d be expected someday to stand his ground. Three times Pete sneaked out of hospitals to play. Once he went back into the lineup after doctors warned him that any blow on the head would kill him. For four years he swung the bat and made the throws when it was painful for him just to shave and to comb his hair. In the 1947 World Series he stood on a broken ankle to pinch hit, and it ended with Rickey, then president of the Dodgers, begging him not to play and guaranteeing Pete his 1948 salary if he would just sit that season out.

“That might be the one mistake I made,” Pete says now. “Maybe I should have rested that year.”

“Pete Reiser?” Leo Durocher, who managed Pete at Brooklyn, was saying recently. “What’s he doing now?”

“He’s managing Kokomo,” Lindsey Nelson, the TV sportscaster, said.

“Kokomo?” Leo said.

“That’s right,” Lindsey said. “He’s riding the buses to places like Lafayette and Michigan City and Mattoon.”

“On the buses,” Leo said, shaking his head and then smiling at the thought of Pete.

“And some people say,” Lindsey said, “that he was the greatest young ballplayer they ever saw.”

“No doubt about it,” Leo said. “He was the best I ever had, with the possible exception of Mays. At that, he was even faster than Willie.” He paused. “So now he’s on the buses.”

The first time that Leo ever saw Pete on a ball field was in Clearwater that spring of ‘39. Pete had played one year of Class D in the Cardinal chain and one season of Class D for Brooklyn. Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who was then baseball commissioner, had sprung Pete and seventy-two others from what they called the “Cardinal Chain Gang,” and Pete had signed with Brooklyn for $100.

“I didn’t care about money then,” Pete says, “I just wanted to play.”

Pete had never been in a major-league camp before, and he didn’t know that at batting practice you hit in rotation. At Clearwater he was grabbing any bat that was handy and cutting in ahead of Ernie Koy or Dolph Camilli or one of the others, and Leo liked that.

One day Leo had a chest cold, so he told Pete to start at shortstop. His first time up he hit a homer off the Cards’ Ken Raffensberger, and that was the beginning. He was on base his first twelve times at bat that spring, with three homers, five singles, and four walks. His first time against Detroit he homered off Tommy Bridges. His first time against the Yankees he put one over the fence off Lefty Gomez.

Durocher played Pete at shortstop in thirty-three games that spring. The Dodgers barnstormed north with the Yankees, and one night Joe McCarthy, who was managing the Yankees, sat down next to Pete on the train.

“Reiser,” he said, “you’re going to play for me.”

“How can I play for you?” Pete said. “I’m with the Dodgers.”

“We’ll get you,” McCarthy said. “I’ll tell Ed Barrow, and you’ll be a Yankee.”

The Yankees offered $100,000 and five ballplayers for Pete. The Dodgers turned it down, and the day the season opened at Ebbets Field, Larry MacPhail, who was running things in Brooklyn, called Pete on the clubhouse phone and told him to report to Elmira.

“It was an hour before game time,” Pete says, “and I started to take off my uniform and I was shaking all over. Leo came in and said, ‘What’s the matter? You scared?’ I said, ‘No. MacPhail is sending me to Elmira.’ Leo got on the phone and they had a hell of a fight. Leo said he’d quit, and MacPhail said he’d fire him—and I went to Elmira.

“One day I’m making a throw and I heard something pop. Every day my arm got weaker and they sent me to Johns Hopkins and took X-rays. Dr. George Bennett told me, ‘Your arm’s broken.’ When I came to after the operation, my throat was sore and there was an ice pack on it. I said, ‘What happened? Your knife slip?’ They said, ‘We took your tonsils out while we were operating on your arm.’”

The Dodgers offered to bet $1,000 that Reiser was the fastest man in baseball, and now it was taking him forever to walk to me, his shoulders stooped, his whole body heavier now, and Pete just slowly moving one foot ahead of the other.

Pete’s arm was in a cast from the first of May until the end of July. His first two weeks out of the cast he still couldn’t straighten the arm, but a month later he played ten games as a left-handed outfielder until Dr. Bennett stopped him.

“But I can’t straighten my right arm,” Pete said.

“Take up bowling,” the doctor said.

When he bowled, though, Pete used first one arm and then the other. Every day that the weather allowed he went out into the backyard and practiced throwing a rubber ball left-handed against a wall. Then he went to Fairgrounds Park and worked on the long throw, left-handed, with a baseball.

“At Clearwater that next spring,” he said, “Leo saw me in the outfield throwing left-handed, and he said, ‘What do you think you’re doin’?’ I said, ‘Hell, I had to be ready. Now I can throw as good with my left arm as I could with my right.’ He said, ‘You can do more things as a right-handed ballplayer. I can bring you into the infield. Go out there and cut loose with that right arm.’ I did and it was okay, but I had that insurance.”

So at five o’clock I took a cab from the hotel in Kokomo to the ball park on the edge of town. It seats about 2,200—1,500 in the white-painted fairgrounds grandstand along the first baseline, and the rest in chairs behind the screen and in bleachers along the other line.

I watched them take batting practice—trim, strong young kids with their dreams, I knew, of someday getting up there where Pete once was—and I listened to their kidding. I watched the groundskeeper open the concession booth and clean out the electric popcorn machine. I read the signs on the outfield walls, advertising the Mid-West Towel and Linen Service, Basil’s Nite Club, the Hoosier Iron Works, UAW Local 292, and the Around the Clock Pizza Café. I watched the Dubuque kids climbing out of their bus, carrying their uniforms on wire coat hangers.

“Here comes Pete now,” I heard the old guy setting up the ticket box at the gate say.

When Pete came through the gate he was walking like an old man. In 1941, the Dodgers trained in Havana, and one day they clocked him, in his baseball uniform and regular spikes, at 9.8 for a hundred yards. Five years later the Cleveland Indians were bragging about George Case and the Washington Senators had Gil Coan. The Dodgers offered to bet $1,000 that Reiser was the fastest man in baseball, and now it was taking him forever to walk to me, his shoulders stooped, his whole body heavier now, and Pete just slowly moving one foot ahead of the other.

“Hello,” he said, shaking hands but his face solemn. “How are you?”

“Fine,” I said, “but what’s the matter with you?”

“I guess it’s my heart,” he said.

“When did you first notice this?”

“About eleven days ago. I guess I was working out too hard. All of a sudden I felt this pain in my chest and I got weak. I went into the clubhouse and lay down on the bench, but I’ve had the same pain and I’m weak ever since.”

“What did the doctor say?”

“He says it’s lucky I stopped that day when I did. He says I should be in a hospital right now, because if I exert myself or even make a quick motion I might go—just like that.”

He snapped his fingers. “He scared me,” he said. “I’ll admit it. I’m scared.”

“What are you planning to do?”

“I’m going home to St. Louis. My wife works for a doctor there, and he’ll know a good heart specialist.”

“When will you leave?”

“Well, I can’t just leave the ball club. I called Brooklyn, and they’re sending a replacement for me, but he won’t be here until tomorrow.”

“How will you get to St. Louis?”

“It’s about three hundred miles,” Pete says. “The doctor says I shouldn’t fly or go by train, because if anything happens to me they can’t stop and help me. I guess I’ll have to drive.”

“I’ll drive you,” I said.

Trying to get to sleep in the hotel that night I was thinking that maybe, standing there in that little ball park, Pete Reiser had admitted out loud for the first time in his life that he was scared. I was thinking of 1941, his first full year with the Dodgers. He was beaned twice and crashed his first wall and still hit .343 to be the first rookie and the youngest ballplayer to win the National League batting title. He tied Johnny Mize with thirty-nine doubles, led in triples, runs scored, total bases, and slugging average, and they were writing on the sports pages that he might be the new Ty Cobb.

“Dodgers Win On Reiser HR,” the headlines used to say. “Reiser Stars as Brooklyn Lengthens Lead.”

“Any manager in the National League,” Arthur Patterson wrote one day in the New York Herald Tribune, “would give up his best man to obtain Pete Reiser. On every bench they’re talking about him. Rival players watch him take his cuts during batting practice, announce when he’s going to make a throw to the plate or third base during outfield drill. They just whistle their amazement when he scoots down the first baseline on an infield dribbler or a well-placed bunt.”

He was beaned the first time at Ebbets Field five days after the season started. A sidearm fastball got away from Ike Pearson of the Phillies, and Pete came to at 11:30 that night in Peck Memorial Hospital.

“I was lying in bed with my uniform on,” he told me once, “and I couldn’t figure it out. The room was dark, with just a little night-light, and then I saw a mirror and I walked over to it and lit the light and I had a black eye and a black streak down the side of my nose. I said to myself, ‘What happened to me?’ Then I remembered.

“I took a shower and walked around the room, and the next morning the doctor came in. He looked me over, and he said, ‘We’ll keep you here for five or six more days under observation.’ I said, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘You’ve had a serious head injury. If you tried to get out of bed right now, you’d fall down.’ I said, ‘If I can get up and walk around this room, can I get out?’ The doc said, ‘All right, but you won’t be able to do it.’ ”

Pete got out of bed, the doctor standing ready to catch him. He walked around the room. “I’ve been walkin’ the floor all night,” Pete said.

The doctor made Pete promise that he wouldn’t play ball for a week, but Pete went right to the ball park. He got a seat behind the Brooklyn dugout, and Durocher spotted him.

“How do you feel?” Leo said.

“Not bad,” Pete said.

“Get your uniform on,” Leo said.

“I’m not supposed to play,” Pete said.

“I’m not gonna play you,” Leo said. “Just sit on the bench. It’ll make our guys feel better to see that you’re not hurt.”

Pete suited up and went out and sat on the bench. In the eighth inning it was tied 7–7. The Dodgers had the bases loaded, and there was Ike Pearson again, coming in to relieve.

Pete always says that the next year, 1942, was the year of his downfall, and the worst of it happened on one play.

“Pistol,” Leo said to Pete, “get the bat.”

In the press box the baseball writers watched Pete. They wanted to see if he’d stand right in there. After a beaning they are all entitled to shy, and many of them do. Pete hit the first pitch into the center field stands, and Brooklyn won, 11–7.

“I could just barely trot around the bases,” Pete said when I asked him about it. “I was sure dizzy.”

Two weeks later they were playing the Cardinals, and Enos Slaughter hit one and Pete turned in center field and started to run. He made the catch, but he hit his head and his tailbone on that corner near the exit gate.

His head was cut, and when he came back to the bench they also saw blood coming through the seat of his pants. They took him into the clubhouse and pulled his pants down and the doctor put a metal clamp on the cut.

“Just don’t slide,” he told Pete. “You can get it sewed up after the game.”

In August of that year big Paul Erickson was pitching for the Cubs and Pete took another one. Again he woke up in a hospital. The Dodgers were having some pretty good bean-ball contests with the Cubs that season, and Judge Landis came to see Pete the next day.

“Do you think that man tried to bean you?” he asked Pete.

“No sir,” Pete said. “I lost the pitch.”

“I was there,” Landis said, “and I heard them holler, ‘Stick it in his ear!’”

“That was just bench talk,” Pete said. “I lost the pitch.”

He left the hospital the next morning. The Dodgers were going to St. Louis after the game, and Pete didn’t want to be left in Chicago.

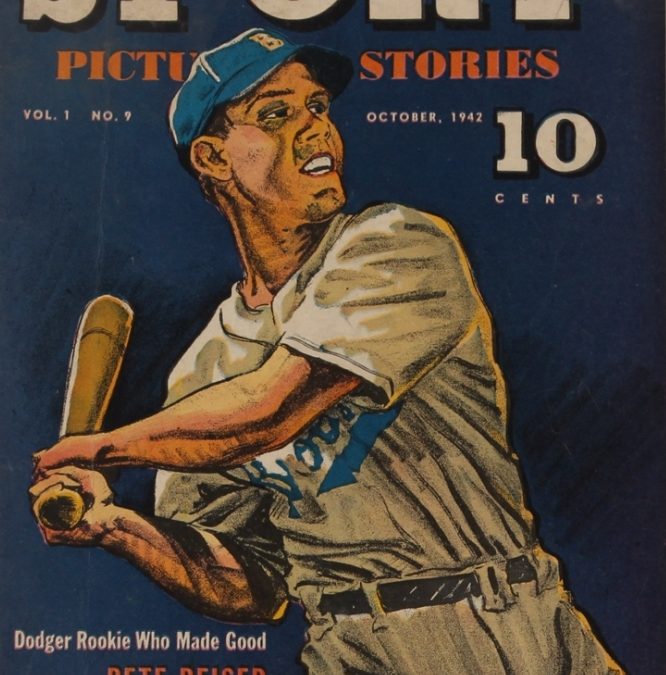

Pete always says that the next year, 1942, was the year of his downfall, and the worst of it happened on one play. It was early July and Pete and the Dodgers were tearing the league apart. Starting in Cincinnati he got 19 for 21. In a Sunday double-header in Chicago he went 5 for 5 in the first game, walked three times in the second game, and got a hit the one time they pitched to him. He was hitting .391, and they were writing in the papers that he might end up hitting .400.

When they came into St. Louis the Dodgers were leading by ten and a half games. When they took off for Pittsburgh they left three games of that lead and Pete Reiser behind them.

“We were in the twelfth inning, no score, two outs, and Slaughter hit it off Whit Wyatt,” Pete says. “It was over my head and I took off. I caught it and missed that flagpole by two inches and hit the wall and dropped the ball. I had the instinct to throw it to Pee Wee Reese, and we just missed gettin’ Slaughter at the plate, and they won, 1–0.

“I made one step to start off the field and I woke up the next morning in St. John’s Hospital. My head was bandaged, and I had an awful headache.”

Dr. Robert Hyland, who was Pete’s personal physician, announced to the newspapers that Pete would be out for the rest of the season. “Look, Pete,” Hyland told him, “I’m your personal friend. I’m advising you not to play any more baseball this year.”

“I don’t like hospitals, though,” Pete was telling me once, “so after two days I took the bandage off and got up. The room started to spin, but I got dressed and I took off. I snuck out, and I took a train to Pittsburgh and I went to the park.

“I’d say I lost the pennant for us that year,” Pete says now, although he still hit .310 for the season. “I was dizzy most of the time and I couldn’t see fly balls. I mean balls I could have put in my pocket, I couldn’t get near.”

“Leo saw me and he said, ‘Go get your uniform on, Pistol.’ I said, ‘Not tonight, Skipper.’ Leo said, ‘Aw, I’m not gonna let you hit. I want these guys to see you. It’ll give ’em that little spark they need. Besides, it’ll change the pitching plans on that other bench when they see you sittin’ here in uniform.’”

In the fourteenth inning the Dodgers had a runner on second and Ken Heintzelman, the left-hander, came in for the Pirates. He walked Johnny Rizzo, and Durocher had run out of pinch hitters.

“Damn,” Leo was saying, walking up and down. “I want to win this one. Who can I use? Anybody here who can hit?”

Pete walked up to the bat rack. He pulled out his stick. “You got yourself a hitter,” he said to Leo.

He walked up there and hit a line drive over the second baseman’s head that was good for three bases. The two runs scored, and Pete rounded first base and collapsed.

“When I woke up I was in a hospital again,” he says. “I could just make out that somebody was standin’ there and then I saw it was Leo. He said, ‘You awake?’ I said, ‘Yep.’ He said, ‘By God, we beat ’em! How do you feel?’ I said, ‘How do you think I feel?’ He said, ‘Aw, you’re better with one leg and one eye than anybody else I’ve got.’ I said, ‘Yeah, and that’s the way I’ll end up—on one leg and with one eye.’

“I’d say I lost the pennant for us that year,” Pete says now, although he still hit .310 for the season. “I was dizzy most of the time and I couldn’t see fly balls. I mean balls I could have put in my pocket, I couldn’t get near. Once in Brooklyn when Mort Cooper was pitching for the Cards I was seeing two baseballs coming up there. Babe Pinelli was umpiring behind the plate, and a couple of times he stopped the game and asked me if I was all right. So the Cards beat us out the last two days of the season.”

The business office of the Kokomo ball club is the dining room of a man named Jim Deets, who sells insurance and is also the business manager of the club. His wife, in addition to keeping house, mothering six small kids, boarding Pete, an outfielder from Venezuela, and a shortstop from the Dominican Republic, is also the club secretary.

“How do you feel this morning?” I asked Pete. He was sitting at the dining-room table, in a sweatshirt and a pair of light brown slacks, typing the game report of the night before to send it to Brooklyn.

“A little better,” he said.

Pete has a worn, green, seven-year-old Chevy, and it took us eight and a half hours to get to St. Louis. I’d ask him how the pain in his chest was and he’d say that it wasn’t bad or it wasn’t so good and I’d get him to talking again about Durocher or about his time in the Army. Pete played under five managers at Brooklyn, Boston, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland, and Durocher is his favorite.

“He has a great mind, and not just for baseball,” Pete said. “Once he sat down to play gin with Jack Benny, and after they’d played four cards Leo read Benny’s whole hand to him. Benny said, ‘How can you do that?’ Leo said, ‘If you’re playin’ your cards right, and I give you credit for that, you have to be holding those others.’ Benny said, ‘I don’t want to play with this guy.’

“One spring at Clearwater there was a pool table in a room off the lobby. One night Hugh Casey and a couple of other guys and I were talking with Leo. We said, ‘Gee, there’s a guy in there and we’ve been playin’ pool with him for a couple of nights, but last night he had a real hot streak.’ Leo said, ‘How much he take you for?’ We figured it out and it was two thousand dollars. Leo said, ‘Point him out to me.’

“We went in and pointed the guy out and Leo walked up to him and said, ‘Put all your money on the table. We’re gonna shoot for it.’ The guy said, ‘I never play like that.’ Leo said, ‘You will tonight. Pick your own game.’ Leo took him for four thousand dollars, and then he threw him out. Then he paid us back what we’d gone for, and he said, ‘Now, let that be a lesson. That guy is a hustler from New York. The next time it happens I won’t bail you out.’ Leo hadn’t had a cue in his hands for years.”

It was amazing that they took Pete into the Army. He had wanted to enlist in the Navy, but the doctors looked him over and told him none of the services could accept him. Then his draft board sent him to Jefferson Barracks in the winter of 1943, and the doctors there turned him down.

“I’m sittin’ on a bench with the other guys who’ve been rejected,” he was telling me, “and a captain comes in and says, ‘Which one of you is Reiser?’ I stood up and I said, ‘I am.’ In front of everybody he said, ‘So you’re trying to pull a fast one, are you? At a time like this, with a war going on, you came in here under a false name. What do you mean, giving your name as Harold Patrick Reiser? Your name’s Pete Reiser, and you’re the ballplayer, aren’t you?’ I said, ‘I’m the ballplayer and they call me Pete, but my right name is Harold Patrick Reiser.’ The captain says, ‘I apologize. Sergeant, fingerprint him. This man is in.’”

They sent him to Fort Riley, Kansas. It was early April and raining and they were on bivouac, and Pete woke up in a hospital. “What happened?” he said.

“You’ve got pneumonia,” the doctor said. “You’ve been a pretty sick boy for six days. You’ll be all right, but we’ve been looking you over. How did you ever get into this Army?”

“When I get out of the hospital,” Pete was telling me, “I’m on the board for a discharge and I’m waitin’ around for about a week, and still nobody there knows who I am. All of a sudden one morning a voice comes over the bitch box in the barracks. It says, ‘Private Reiser, report to headquarters immediately.’ I think, ‘Well, I’m out now.’

“I go over there and the colonel wants to see me. I walk in and give my good salute and he says, ‘Sit down, Harold.’ I sit down and he says, ‘Your name really isn’t Harold, is it?’ I say, ‘Yes it is, sir.’ He says, ‘But that isn’t what they call you when you’re well-known, is it? You’re Pete Reiser the ballplayer, aren’t you?’ I say, ‘Yes, sir.’ He says, ‘I thought so. Now, I’ve got your discharge papers right there, but we’ve got a pretty good ball club and we’d like you on it. We’ll make a deal. You say nothing, and you won’t have to do anything but play ball. How about it?’ I said, ‘Suppose I don’t want to stay in?’ He picked my papers up off his desk, and he tore ’em right up in my face. I can still hear that ‘zip’ when he tore ’em. He said, ‘You see, you have no choice.’

“Then he picked up the phone and said something and in a minute a general came in. I jumped up and the colonel said, ‘Don’t bother to salute, Pete.’ Then he said to the general, ‘Major, this is Pete Reiser, the great Dodger ballplayer. He was up for a medical discharge, but he’s decided to stay here and play ball for us.’

“So the general says, ‘My, what a patriotic thing for you to do, young man. That’s wonderful. Wonderful.’ I’m sittin’ there, and when the general goes out the colonel says, ‘That major, he’s all right.’ I said, ‘But he’s a general. How come you call him a major?’ The colonel says, ‘Well, in the regular Army he’s a major and I’m a full colonel. The only reason I don’t outrank him now is that I’ve got heart trouble. He knows it, but I never let him forget it. I always call him major.’ I thought, ‘What kind of an Army am I in?’”

“And here comes Pistol Pete Reiser!” the announcer said. “Where do you think you’ll finish this season, Pete?”

“In Peck Memorial Hospital,” Pete said.

Joe Gantenbein, the Athletics’ outfielder, and George Scharein, the Phillies’ infielder, were on that team with Pete, and they won the state and national semi-pro titles. By the time the season was over, however, the order came down to hold up all discharges.

The next season there were seventeen major-league ballplayers on the Fort Riley club, and they played four nights a week for the war workers in Wichita. Pete hit a couple of walls, and the team made such a joke of the national semi-pro tournament that an order came down from Washington to break up the club.

“Considering what a lot of guys did in the war,” Pete says, “I had no complaints, but five times I was up for discharge, and each time something happened. From Riley they sent me to Camp Livingston. From there they sent me to New York Special Services for twelve hours and I end up in Camp Lee, Virginia, in May 1945.

“The first one I meet there is the general. He says, ‘Reiser, I saw you on the list and I just couldn’t pass you up.’ I said, ‘What about my discharge?’ He says, ‘That will have to wait. I have a lot of celebrities down here, but I want a good baseball team.’”

Johnny Lindell, of the Yankees, and Dave Philley, of the White Sox, were on the club and Pete played left field. Near the end of the season he went after a foul fly for the third out of the last inning, and he went right through a temporary wooden fence and rolled down a twenty-five-foot embankment.

“I came to in the hospital with a dislocated right shoulder,” he says, “and the general came over to see me and he said, ‘That was one of the greatest displays of courage I’ve ever seen, to ignore your future in baseball just to win a ball game for Camp Lee.’ I said, ‘Thanks.’

“Now it’s November and the war is over, but they’re still shippin’ guys out, and I’m on the list to go. I report to the overseas major, and he looks at my papers and says, ‘I can’t send you overseas. With everything that’s wrong with you, you shouldn’t even be in this Army. I’ll have you out in three hours.’ In three hours, sure enough, I’ve got those papers in my hand, stamped, and I’m startin’ out the door. Runnin’ up to me comes a Red Cross guy. He says, ‘I can get you some pretty good pension benefits for the physical and mental injuries you’ve sustained.’ I said, ‘You can?’ He said, ‘Yes, you’re entitled to them.’ I said, ‘Good. You get ‘em. You keep ‘em. I’m goin’ home.’”

When we got to St. Louis that night I drove Pete to his house and the next morning I picked him up and drove him to see the heart specialist. He was in there for two hours, and when he came out he was walking slower than ever.

“No good,” he said. “I have to go to the hospital for five days for observation.”

“What does he think?”

“He says I’m done puttin’ on that uniform, I’ll have to get a desk job.”

Riding to the hospital I wondered if that heart specialist knew who he was tying to that desk job. In 1946, the year he came out of the Army, Pete led the league when he stole thirty-four bases, thirteen more than the runner-up, Johnny Hopp of the Braves. He also set a major-league record that still stands, when he stole home seven times.

“Eight times,” he said once. “In Chicago I stole home and Magerkurth hollered, ‘You’re out!’ Then he dropped his voice and he said, ‘Sonofabitch! I missed it.’ He’d already had his thumb in the air. I had eight out of eight.”

I suppose somebody will beat that someday, but he’ll never top the way Pete did it. That was the year he knocked himself out again making a diving catch, dislocated his left shoulder, ripped the muscles in his left leg, and broke his left ankle.

“Whitey Kurowski hit one in the seventh inning at Ebbets Field,” he was telling me. “I dove for it and woke up in the clubhouse. I was in Peck Memorial for four days. It really didn’t take much to knock me out in those days. I was comin’ apart all over. When I dislocated my shoulder they popped it back in, and Leo said, ‘Hell, you’ll be all right. You don’t throw with it anyway.’”

That was the year the Dodgers tied with the Cardinals for the pennant and dropped the playoff. Pete wasn’t there for those two games. He was in Peck Memorial again.

“I’d pulled a charley horse in my left leg,” Pete was saying. “It’s the last two weeks of the season, and I’m out for four days. We’ve got the winning run on third, two outs in the ninth, and Leo sends me up. He says, ‘If you don’t hit it good, don’t run and hurt your leg.’

“The first pitch was a knockdown and, when I ducked, the ball hit the bat and went down the third baseline, as beautiful a bunt as you’ve ever seen. Well, Ebbets Field is jammed. Leo has said, ‘Don’t run.’ But this is a big game. I take off for first, and we win and I’ve ripped the muscles from my ankle to my hip. Leo says, ‘You shouldn’t have done it.’

“Now it’s the last three days of the season and we’re a game ahead of the Cards and we’re playin’ the Phillies in Brooklyn. Leo says to me, ‘It’s now or never. I don’t think we can win it without you.’ The first two up are outs and I single to right. There’s Charley Dressen, coachin’ on third, with the steal sign. I start to get my lead, and a pitcher named Charley Schanz is workin’ and he throws an ordinary lob over to first. My leg is stiff and I slide and my heel spike catches the bag and I hear it snap.

“Leo comes runnin’ out. He says, ‘Come on. You’re all right.’ I said, ‘I think it’s broken.’ He says, ‘It ain’t stickin’ out.’ They took me to Peck Memorial, and it was broken.”

We went to St. Luke’s Hospital in St. Louis. In the main office they told Pete to go over to a desk where a gray-haired, semistout woman was sitting at a typewriter. She started to book Pete in, typing his answer on the form. “What is your occupation, Mr. Reiser?” she said.

“Baseball,” Pete said.

“Have you ever been hospitalized before?”

“Yes,” Pete said.

In 1946, the Dodgers played an exhibition game in Springfield, Missouri. When the players got off the train there was a young radio announcer there, and he was grabbing them one at a time and asking them where they thought they’d finish that year.

Pete was unable to hold even a pencil. He had double vision and when he tried to take a single step, he became dizzy. He stayed for three weeks and then went home for almost a month.

“In first place,” Reese and Casey and Dixie Walker and the rest were saying. “On top.” “We’ll win it.”

“And here comes Pistol Pete Reiser!” the announcer said. “Where do you think you’ll finish this season, Pete?”

“In Peck Memorial Hospital,” Pete said.

After the 1946 season Brooklyn changed the walls at Ebbets Field. They added boxes, cutting forty feet off left field and dropping center field from 420 to 390 feet. Pete had made a real good start that season in center, and on June 5 the Dodgers were leading the Pirates by three runs in the sixth inning when Culley Rikard hit one.

“I made my turn and ran,” Pete says, “and, where I thought I still had that thirty feet, I didn’t.”

“The crowd,” Al Laney wrote the next day in the New York Herald Tribune, “which watched silently while Reiser was being carried away, did not know that he had held on to the ball…. Rikard circled the bases, but Butch Henline, the umpire, who ran to Reiser, found the ball still in Reiser’s glove…. Two outs were posted on the scoreboard after play was resumed. Then the crowd let out a tremendous roar.”

In the Brooklyn clubhouse the doctor called for a priest, and the last rites of the Church were administered to Pete. He came to, but lapsed into unconsciousness again and woke up at 3:00 A.M. in Peck Memorial.

For eight days he couldn’t move. After three weeks they let him out, and he made the next western trip with the Dodgers. In Pittsburgh he was working out in the outfield before the game when Clyde King, chasing a fungo, ran into him and Pete woke up in the clubhouse.

“I went back to the Hotel Schenley and lay down,” he says. “After the game I got up and had dinner with Pee Wee. We were sittin’ on the porch, and I scratched my head and I felt a lump there about as big as half a golf ball. I told Pee Wee to feel it and he said, ‘Gosh!’ I said, ‘I don’t think that’s supposed to be like that.’ He said, ‘Hell, no.’”

Pete went up to Rickey’s room and Rickey called his pilot and had Pete flown to Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. They operated on him for a blood clot.

“You’re lucky,” the doctor told him. “If it had moved just a little more you’d have been gone.”

Pete was unable to hold even a pencil. He had double vision and when he tried to take a single step, he became dizzy. He stayed for three weeks and then went home for almost a month.

“It was August,” he said, “and Brooklyn was fightin’ for another pennant. I thought if I could play the last two months it might make the difference, so I went back to Johns Hopkins. The doctor said, ‘You’ve made a remarkable recovery.’ I said, ‘I want to play.’ He said, ‘I can’t okay that. The slightest blow on the head can kill you.’ ”

Pete played. He worked out for four days, pinch hit a couple of times, and then, in the Polo Grounds, made a diving catch in left field. They carried him off, and in the clubhouse he was unable to recognize anyone.

Pete was still having dizzy spells when the Dodgers went into the 1947 Series against the Yankees. In the third game he walked in the first inning, got the steal sign, and, when he went into second, felt his right ankle snap. At the hospital they found it was broken.

“Just tape it, will you?” Pete said.

“I want to put a cast on it,” the doctor said.

“If you do,” Pete said, “they’ll give me a dollar-a-year contract next season.”

The next day he was back on the bench. Bill Bevens was pitching for the Yankees and, with two out in the ninth, it looked like he was going to pitch the first no-hitter in World Series history.

“Aren’t you going to volunteer to hit?” Burt Shotton, who was managing Brooklyn, said to Pete.

Al Gionfriddo was on second and Bucky Harris, who was managing the Yankees, ordered Pete walked. Eddie Miksis ran for him, and when Cookie Lavagetto hit that double, the two runners scored and Brooklyn won, 3–2.

“The next day,” Pete says, “the sportswriters were second-guessing Harris for putting me on when I represented the winning run. Can you imagine what they’d have said if they knew I had a broken ankle?”

At the end of that season Rickey had the outfield walls at Ebbets Field padded with one-inch foam rubber for Pete, but he never hit them again. He had headaches most of the time and played little. Then he was traded to Boston, and in two seasons there he hit the wall a couple of times. Twice his left shoulder came out while he was making diving catches. Pittsburgh picked Pete up in 1951, and the next year he played into July with Cleveland and that was the end of it.

Between January and September 1953, Pete dropped $40,000 in the used-car business in St. Louis, and then he got a job in a lumber mill for $100 a week. In the winter of 1955, he wrote Brooklyn asking for a part-time job as a scout, and on March 1, Buzzy Bavasi, the Dodger vice president, called him on the phone.

“How would you like a manager’s job?” Buzzy said.

“I’ll take it,” Pete said.

“I haven’t even told you where it is. It’s Thomasville, Georgia, in Class D.”

“I don’t care,” Pete said. “I’ll take it.”

At Vero Beach that spring, Mike Gaven wrote a piece about Pete in the New York Journal-American.

“Even in the worn gray uniform of the Class D Thomasville, Georgia, club,” Mike wrote, “Pete Reiser looks, acts, and talks like a big leaguer. The Dodgers pitied Pete when they saw him starting his comeback effort after not having handled a ball for two and a half years. They lowered their heads when they saw him in a chow line with a lot of other bushers, but the old Pistol held his head high…’’

The next spring, Sid Friedlander, of the New York Post, saw Pete at Vero and wrote a column about him managing Kokomo. The last thing I saw about him in the New York papers was a small item out of Tipton, Indiana, saying that the bus carrying the Kokomo team had collided with a car and Pete was in a hospital in Kokomo with a back injury.

“Managing,” Pete was saying in that St. Louis hospital, “you try to find out how your players are thinking. At Thomasville one night one of my kids made a bad throw. After the game I said to him, ‘What were you thinking while that ball was coming to you?’ He said, ‘I was saying to myself that I hoped I could make a good throw.’ I said, ‘Sit down.’ I tried to explain to him the way you have to think. You know how I used to think?”

“Yes,” I said, “but you tell me.”

“I was always sayin’, ‘Hit it to me. Just hit it to me. I’ll make the catch. I’ll make the throw.’ When I was on base I was always lookin’ over and sayin’, ‘Give me the steal sign. Give me the sign. Let me go.’ That’s the way you have to think.”

“Pete,” I said, “now that it’s all over, do you ever think that if you hadn’t played it as hard as you did, there’s no telling how great you might have been or how much money you might have made?”

“Never,” Pete said. “It was my way of playin’. If I hadn’t played that way I wouldn’t even have been whatever I was. God gave me those legs and the speed, and when they took me into the walls that’s the way it had to be. I couldn’t play any other way.”

A technician came in with an electrocardiograph. She was a thin, dark-haired woman and she set it up by the bed and attached one of the round metal disks to Pete’s left wrist and started to attach another to his left ankle.

“Aren’t you kind of young to be having pains in your chest?” she said.

“I’ve led a fast life,” Pete said.

On the way back to New York I kept thinking how right Pete was. To tell a man who is this true that there is another way for him to do it is to speak a lie. You cannot ask him to change his way of going, because it makes him what he is.

Three days after I got home I had a message to call St. Louis. I heard the phone ring at the other end and Pete answered. “I’m out!” he said.

“Did they let you out, or did you sneak out again?” I said.

“They let me out,” he said. “It’s just a strained heart muscle, I guess. My heart itself is all right.”

“That’s wonderful.”

“I can manage again. In a couple of days I can go back to Kokomo.” If his voice had been higher he would have sounded like a kid at Christmas.

“What else did they say?” I said.

“Well, they say I have to take it easy.”

“Do me a favor,” I said.

“What?”

“Take their advice. This time, please take it easy.”

“I will,” he said. “I’ll take it easy.”

If he does it will be the first time.