The big mole. The American Philby. Is he still among us, still a trusted figure operating at the highest levels of government, still burrowing ever deeper into our most sensitive secrets, as embittered exiles from our espionage establishment, the losing side in the Great Mole War of the past decade, contend? Is he, even now, sitting in some comfortable Capitol district office and reading these words, chuckling contentedly?

Or did he ever exist at all? Might he be a delusion engendered by the fevered fantasies of the hierophants of counterintelligence theory—a product of paranoid “sick think,” as the complacent victors in the Great Mole War, the current chiefs of the espionage establishment, have called it? Worse, might the entire twelve-year-long hunt for the American mole and the civil war within the clandestine world that it created have been a massive deception operation? Might Big Mole merely be a chimera craftily conjured up by the KGB of Kim Philby and Yuri Andropov in order to provoke and profit from the divisiveness and paralysis, the self-destructive finger-pointing futility that followed?

For those of you whose knowledge of mole literature is limited to Le Carré’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, and who might still assume that somewhere, somehow, some real-life George Smiley has tracked down some real-life Big Mole and mopped up the stain of treachery—well, the real-life case of the Big Mole, the frenzied twelve-year hunt for the American Philby, makes the complications of Tinker, Tailor seem like the child’s play of the title.

Because we have serious matters to consider here. Deadly serious: charges of treason, unresolved allegations against individuals at the very heart of the heart of the American diplomatic and intelligence establishment, some still in government service. We’re talking about careers ruined, about mass resignations of counterintelligence people convinced that the CIA has been irrevocably penetrated by KGB pawns, about men we thought were our moles in Moscow arrested and shot, and about schizophrenic distortions of our own perceptions of Soviet policy.

But before we start naming names of Big Mole suspects—and I happen to have a little list—before we plunge into the murky waters of mole literature for some conjectural detective work, let’s look at the Big Mole mystery in historical perspective.

Since the flight to Moscow in 1951 of British foreign-service moles Guy Burgess and Donald McLean, and the forced retirement of suspected “Third Man” Kim Philby, every other major Western nation has been rocked to its secret core by the discovery that one or more of its highest-ranking clandestine-service chiefs had been a KGB penetration agent. The French had their sapphire ring; the heads of West German counterintelligence, of Swedish counterintelligence, of Canadian counterintelligence have all been convicted or forced into retirement because of mole allegations. Most recently, in Britain, Sir Roger Hollis, the head of MI5, the British FBI—James Bond’s boss, for God’s sake—has all but been convicted posthumously of being a mole.

But not us. Not here. Which means one of two things: that we’re immune, we can trust each other, the word of a gentleman among the old-school-tie aristocrats who founded our clandestine and diplomatic services has proved its worth against betrayal. Or that we just haven’t uncovered our Big Mole yet.

Not that there haven’t been suspects. Averell Harriman. Henry Kissinger. Former CIA head William Colby. Former White House speech writer Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. Two former chiefs of the CIA’s Soviet Bloc division, three other high-ranking CIA executives. Even the CIA’s chief mole-hunter, counterintelligence guru James Angleton himself—all have been named at one time or another as possible KGB penetration agents by CIA colleagues or defectors from the KGB.

None of the allegations against them has been proved. And yet in the absence of a definitive discovery of the Big Mole—or proof that his existence is a sophisticated Soviet disinformation plot—the allegations fester in the files, poisoning the perceptual apparatus of the West, paralyzing—for better or worse—the entire espionage establishment, making it impossible for us to trust what we know about the Soviet Union, or know what we trust.

At the heart of this continuing corrosive confusion, doubt, and ambiguity is the mysterious relationship between British master mole Kim Philby and America’s master mole-hunter James Angleton. Although it has been a deadly serious duel that’s stretched over three decades, the relationship has come to include elements of an incongruously intimate marriage: not unlike a real-life version of the deadly embrace between Le Carré’s Smiley and Karla. But a marriage whose complexities and ambiguities make that one seem like Ozzie and Harriet’s by comparison.

On the surface the outcome seems long established. There is Philby, generally acknowledged to be the most successful spy of the century, comfortably established in Moscow, a colonel-general in the KGB, now even more exalted by virtue of his longtime close collaboration with former KGB boss Yuri Andropov. And there is Angleton, the acknowledged genius of counterintelligence—spying out spies—in the West, whose brilliant career bears one ineradicable scar: his failure, by all official accounts, to detect or even suspect Kim Philby’s true Soviet loyalties despite years of face-to-face contact with the spy of the century.

Angleton. On the outside now. Fired from the CIA for fingering one too many of his fellow operatives in his search for the American Philby, a crippling obsession his detractors claim was fueled by rage at his failure to discover the perfidy of the original Philby. Angleton, leader of the losing faction in the mole wars, now an embittered exile who occupies his time growing orchids and orchestrating a subterranean information war against the winning side, portraying the powers-that-be at the CIA as doing the bidding of the Big Mole, who is himself doing the bidding of KGB colonel Kim Philby, his triumphant creator.

And yet buried in the literature are provocative hints—sometimes surfacing only in cryptic footnotes—that there is an entirely different way of looking at this picture. Indeed, every element in the Philby-Angleton relationship, every clue to the identity of the Big Mole, is shadowed by an ambiguity that points to certain unsettling and unexpected interpretations.

Let’s start with a wedding. The year is 1934; we’re in Vienna. In the streets outside, Austrian Nazis are gunning down the socialist opposition. Inside, a curious clandestine marriage ceremony is being celebrated. The bride: an Austrian communist named Litzi Friedman, on the run from the fascist police. The groom: a twenty-two-year-old, Cambridge-educated English aristocrat named Kim Philby, the son of famed “Arabist” St. John Philby, a scholar-adventurer who was to the Empty Quarter of Arabia what Lawrence was to Transjordan.

What was Kim Philby doing marrying a member of the communist underground? It was a question that might have troubled his colleagues in MI6, the British secret service, had they known about it when they recruited him a few years later. At that time he had been posing as a sympathizer of the Fascist cause in Spain, and the contradiction might have raised warning flags. Knowledge of a secret marriage to a Stalinist might have caused MI6 to proceed with more caution a decade later, when they promoted Philby to the Soviet desk in counterespionage and put him in charge of telling the Western alliance the secret meaning of Stalin’s foreign policy. The implications of the clandestine ceremony might have made the American secret services more wary when Philby arrived in Washington in 1949 and—as chief liaison with the FBI and CIA—was given carte blanche access to every secret our secret services had. It might have helped nail Philby as the mysterious Third Man who tipped off the British Foreign Office spies who fled to Moscow in 1951.

But did that marriage entirely escape the notice of those who might have made use of it? In fact it seems there were at least two who knew. One was a witness at the wedding. The other was James Angleton, American chief of counterespionage, who learned of it from the witness.

The witness was Teddy Kollek. Now mayor of Jerusalem, then a social democratic activist in Vienna. After the war, Kollek, along with other members of Jewish intelligence, came in contact with Angleton when they were running missions to Palestine from Rome, and Angleton was OSS station chief in the Italian capital.

That liaison became extremely close over the years, an emotional as well as strategic affinity. Later, because the Mossad would not trust anyone in American intelligence other than Angleton, he retained sole command of the Israeli desk in the CIA even when he shifted to being chief of counterintelligence. In 1949, Kollek visited Washington on a “trade mission” for the newly established Jewish state. We know he spent time renewing his close friendship with Angleton. We know that at the same time Angleton was having weekly lunches with the liaison officer for the British Secret Intelligence Service, a man named Kim Philby. Since Angleton was fired from the CIA in 1974, several accounts have surfaced that suggest Angleton was tipped off to the truth about Kim Philby’s Soviet mission by Kollek and his colleagues in Israeli intelligence.

The story first appeared in a cryptic footnote. Back in 1977, William Corson, author of a study of the clandestine world called Armies of Ignorance, cited an unnamed source in a footnote to the effect that “Israeli intelligence had detected the activities of Burgess, McLean, and Philby and that the CIA and SIS were thus in a position … to use them as conduits for false information.”

The implications of the footnote were so shocking—requiring a rewriting of the entire postwar history of espionage, and perhaps of diplomacy too—that most experts flatly refused to accept it. In a critical footnote in his biography of CIA chief Richard Helms, writer Thomas Powers suggested the Corson footnote itself must have been “disinformation” planted by Philby’s enemies, a black “valentine” sent to Philby by the CIA to arouse distrust of him among his KGB bosses.

But the story would not die. It cropped up again in Andrew Boyle’s The Fourth Man, a book that attracted the most attention for its public exposure of the Queen’s curator, Anthony Blunt, as the “Fourth Man” in the Philby Ring of Five. But the real bombshell in the Boyle book once again involves the purported Israeli intelligence tip-off to Angleton. This time with a potentially more sinister twist to it.

According to Boyle, Kollek (identified only as a London-based Jewish intelligence operative who “still occupies a prominent and respected position in public life”) “passed on to Angleton the name of the British nuclear scientist who they had unearthed as an important Soviet agent … ‘Basil,’ the code name of the Fifth Man” of the Philby-McLean-Burgess Ring of Five.

Others have disputed Boyle’s candidate for Fifth Man, but the crucial difference between this story and the Corson footnote is that Boyle makes the turning and “playback” of the Ring of Five not a joint CIA and SIS operation but a private Angleton ploy. Angleton ran “the operation out of his hip pocket for at least a couple of years,” says Boyle. “Playing a deep game,” he kept it from the British entirely, and from his fellow Americans. According to Boyle, Allen Dulles himself never learned the “deep game.”

But just how deep was that game? And why did he keep it to himself? Could it still be going on? The implication of the Corson and Boyle stories is that, contrary to the conventional history, from the late 1940s on, Kim Philby was James Angleton’s patsy. And may still be. Angleton did nothing to discourage that impression when I called him to ask for comment. Although he would not confirm or deny it directly, when I asked him if he’d been tipped off about Philby by Israeli intelligence there was a long pause on the line, following which Angleton said, with great deliberation, “My Israeli friends have always been among the most loyal I’ve had. Perhaps the only ones to remain loyal.” He refused to comment further on this or any other substantive intelligence matter, with one cryptic exception.

Deflected from interpretation of intelligence literature, Angleton and I drifted into a discussion of the intelligence of literary interpretation. We expressed our mutual preference for the practitioners of the New Criticism that prevailed at Yale when Angleton was there in the Thirties to the theories of the so-called Yale critics who had come to rule the roost when I arrived there in the Sixties. Angleton boasted to me that he had recruited some of the best minds of the New Critics and poets into the OSS, where their facility at teasing out seven types of ambiguity from a text served them well in the interpretation of the ambiguities of intelligence data. Finally, I returned to the question of Angleton and Philby—just who knew what about whom. Once again he declared he was “unable to comment.” Why not confirm or deny the Boyle story, I asked? After all, it was an event that took place thirty years in the past.

“What you have to understand about these matters,” Angleton said again, with great deliberation, “is that the past telescopes into the present.”

The past telescopes into the present. The implication is that the “deep game” is still going on, that the credibility of disinformation played back through Philby and his Ring of Five, following the Teddy Kollek tip-off, could not be compromised even now by Angleton’s taking credit for the success of the ploy.

Needless to say, there will be those among Angleton’s many critics who would say that the whole notion of this “deep game” was carefully planted by Angleton and his allies in an attempt to turn his most mortifying failure—the Philby case—into a clandestine success.

But there is an even darker interpretation of the fact that Angleton played this whole game “out of his hip pocket” for so long. Some might be tempted to say Angleton was protecting Philby and friends for at least two crucial years between the time his Israeli friends tipped him off and the spring of 1951, when a break in KGB ciphers finally led the British to close in on Philby’s cohorts, McLean and Burgess, and to put the Cambridge spy ring out of business. Later, in 1974, when a member of the CIA counterintelligence staff compiled a voluminous compendium of circumstantial evidence suggesting that mole-hunter Angleton was himself the Big Mole, his putative knowledge of that wedding and his hip-pocket treatment of its implications did nothing to diminish the shadows of ambiguity that darkened around him in the final days of the mole wars.

Was Philby running Angleton? Was Angleton running Philby? Does either of them know for sure?

Somehow it all comes down to what was really transacted between the two of them during those long lobster lunches at Harvey’s restaurant.

Washington, 1949. Harvey’s restaurant. J. Edgar Hoover’s favorite lunch spot. Philby and Angleton begin meeting there once a week. There is official business to transact. Philby is stationed in Washington as liaison officer for His Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service, Angleton as head of the CIA’s Office of Strategic Operations. Their mission: to exchange secrets. Angleton to brief Philby on what the CIA has learned about the Soviets through uniquely American assets, Philby to brief Angleton on what the British have learned from their special resources. All to further the Special Relationship.

But there is more to it than that. There is a special relationship growing between the two men. “Our close association was, I am sure, inspired by genuine friendliness on both sides,” Philby writes. “Our discussions ranged over the whole world.” Yes. They were teacher and pupil once. Philby had taught Angleton the “double-cross system” in 1943 in London when Angleton was an OSS novice. Now they were equals, two brilliant, highly civilized men who shared a more intimate and knowing view of the hidden reality of world affairs than any other two one could think of, the communion of blood brothers in the most secret of secret societies in the West.

“But,” Philby writes, “we both had ulterior motives.”

Indeed. In his memoirs, obviously written under the watchful eye of his KGB superiors, Philby assures us he knows just what the ulterior ambitions on each side of the lobster-stained tablecloth were.

Philby tells us that he was aware that Angleton was “cultivating me to the full,” but he explains Angleton’s motive in this as merely a bureaucratic maneuver. British-American intelligence liaison was carried on by bilateral contacts in both Washington and London. Philby tells us that Angleton wanted to give the CIA London station, which Philby says was ten times bigger than the British one, the key responsibility for the two-way flow of secret-sharing between the allies. “By cultivating me to the full” in Washington, Philby writes, Angleton “could better keep me under wraps” and shift the locus of secret-sharing to London, where the CIA would have more leverage.

After giving us this curiously detailed and somehow unconvincing analysis of Angleton’s motive, Philby lapses into an uncharacteristic bit of boastfulness, in a memoir otherwise distinguished by a dry and reticent wit when it comes to describing the cleverness of his duplicitous achievements. In a passage that one suspects may have been meant for the eyes of the KGB analysts doing a prepublication check into his manuscript, Philby writes:

For my part I was more than content to string [Angleton] along. The greater the trust between us overtly, the less he would suspect covert action. Who gained most from this complex game l cannot say. But l had one big advantage. I knew what he was doing for CIA, and he knew what I was doing for SIS. But the real nature of my interest was something he did not know.

Or did he? If we accept the implications of the Corson footnote, Angleton was “keeping Philby under wraps” and “cultivating him to the full” for very different reasons. By this analysis, Angleton knew exactly what Philby’s “complex game” was about and it was Philby, not Angleton, who was being played for the fool. Angleton was feeding him not real secrets but carefully cooked disinformation along with his crustaceans.

On the other hand, it is not impossible to imagine the two of them together, fellow initiates into the secrets of both sides, playing both sides in the Cold War for fools in a great game of their own devising.

If there is any answer to the perplexities presented to an analyst of the Angleton-Philby lunches, I believe it just may have been cryptically encapsulated by Philby in an ostensibly jovial aside on the difference in weight gains the two master spies displayed as a result of their weekly pig-outs.

Angleton, Philby writes, “was one of the thinnest men I have ever met, and one of the biggest eaters. Lucky Jim! After a year of keeping up with Angleton I took the advice of an elderly lady friend and went on a diet, dropping from thirteen stone to about eleven in three months.” (Italics mine.)

Angleton, in other words, is able to consume and conceal the consequences of consumption—his very metabolism betraying a talent for covertness. Philby, however, finds himself consuming more than is good for him until someone points out that it has disfigured his profile. Is there some self-awareness on Philby’s part that Angleton has been feeding him a diet of disinformation—which he only later learns from a mysterious outsider (who was that lady?)—that he must disgorge from his body of knowledge?

Whatever the deeper nature of the game, an observer present at these lunches would have been privileged to witness one of the most extraordinary confrontations—or collaborations—in the history of intelligence. A seven-course feast of seven types of ambiguity.

But of course these were no mere intellectual games being played. Before we get deeper into the ambiguities of the strange marriage between Philby and Angleton, let’s look a little more closely at why we should care. Let’s look at the absolutely crucial role Kim Philby played in creating the entire perceptual structure of the Cold War from its very inception.

In a certain respect, while Le Carré’s works have popularized the concept of the mole as the representative of the divided character of the West, the association of Philby with Le Carré’s archmole, Bill Haydon, in Tinker, Tailor has diminished the true significance of Philby’s role. In Tinker, Tailor Haydon is referred to knowingly as “our latter-day Lawrence of Arabia,” an unmistakable reference to Philby, whose father is almost always referred to as “the famed Arabist St. John Philby,” and who played a Lawrencian role in the great game of imperial Arabian politics.* There are other touches linking Le Carré’s Haydon and Philby—both compulsively seductive, but sexually ambiguous, Cambridge-educated aesthetes who became Marxists in the Thirties, men of sensibility who retained the supremely arrogant character and the corrosive self-contempt of the aristocratic ironist.

[*Oddly enough, it is none other than the great Lawrence himself who may have given us the missing clue to the origin of Philby’s true loyalties. I have come across a piece of evidence I have not seen referred to anywhere else in the literature that sheds intriguing new light on the Philby family’s true politics. It’s a previously unpublished letter from Lawrence that appears as an offering in the private catalogue of a dealer in rare books and autographs. While the letter, dated 1932, is advertised by the dealer as a missive “linking” Lawrence with “Notorious Communist Spy ‘Kim’ Philby,” this is perhaps an unintentional mistake. The internal dating of the letter (a remark that “Philby took my place at Amman later in 1921”—when Kim Philby was only nine years old) makes it clear that Lawrence is referring to Kim’s father, the Arabist St. John Philby.

What is fascinating about the letter for our purposes is Lawrence’s characterization of the elder Philby as “rather a ‘red’; but decent—very.”

Some commentators, including Le Carré himself, have speculated that the younger Philby’s Marxist motivations may have had their genesis in a reaction against his father’s presumed old-fashioned imperialist “Great Game” politics. Nowhere in the literature is there any suggestion that the elder Philby was “rather a red.” Could it be that he too had been playing a great game of concealment, and that Kim was not rebelling against but carrying on a family tradition of grand duplicity?]

While this makes for literary interest in Le Carré’s recurrent moral debate between sense and sensibility, it reduces our appreciation of the geopolitical significance of Philby’s role. Because Kim Philby was nothing less than a visionary, a demonic one, but still perhaps the best-placed and most effective visionary of the postwar world.

Let’s recall Philby’s precise position in the years 1944–1949. Recruited by the Soviets in 1933, Philby writes in his memoirs: “I was given the assignment to infiltrate counterespionage however long it took.”

It took him eleven years. By then he had not merely infiltrated counterespionage, he was running the entire British counterespionage operation against the Soviets while working for the KGB. What that meant was that during the crucial period when the wartime alliance between the West and the Soviet Union was shifting into the postwar schism, Philby was the one person whose job it was to tell the West about the secret intentions and motivations of the Soviets, and to tell the Soviets about those of the West.

In this absolutely unique, Janus-like role, he was more than any single man able to create the reality of each side for the other. How accurate the reciprocal images of East and West he created, how much the character of the postwar world is the result of Philby’s double vision, is something only Philby knows. While Philby tells us in his memoirs that he was faithfully serving the Soviet Union’s instructions, those memoirs were written and edited in Moscow under the protection and control of the KGB. Which side he was really serving, or whether he was playing a deep game of his own, is something we may never know for sure. But it is useful to recall that his lifelong nickname, “Kim,” came from the Rudyard Kipling character—the half-British, half-Indian boy who was initiated into the breathtakingly exhilarating mysteries of “the Great Game” of duplicity, deception, and manipulation as it was played by the British in their vast Asian empire. Those who played it frequently felt less loyalty to their employers of record than to the game itself.

Nor has the possibility that Philby’s game was deeper, his vision more personal and individual than ideological, escaped the attention of both sides he was playing with. At crucial stages in his career, even after he was ostensibly exposed in 1951 as the Third Man, doubts have emerged as to the locus of his ultimate loyalty.

Take the Otto John case. The year is 1954. Three years after the Third Man case explodes, Burgess and McLean have fled to Moscow, although nobody knows they’re there yet. Philby has been repeatedly interrogated as the suspected Third Man who tipped the two of them off, but the best interrogators in the business have not been able to crack his denials. The secret world of the West is divided on the issue of Philby’s loyalty. The CIA, the FBI, and MI5 are convinced he’s a long-term mole and have forced him into retirement. But Philby’s old outfit, MI6, contains a number of old-school-tie partisans of Kim’s who believe he’s a victim of American McCarthyite paranoia. Although he’s been forced into retirement, secret-service contacts have been arranging employment and financing for him.

Meanwhile, on a July night in West Berlin, Dr. Otto John, head of the BND, the West German equivalent of the FBI, goes out for a night of drinking. Sometime during the night he is drugged, kidnapped, and dragged across the border to East Berlin. That’s his story. By another version he deliberately defects to the East. For a year nothing is heard of him. Then suddenly he reappears in West Berlin, claiming to have escaped KGB captivity.

To this day no one is sure what the real story is. “Whole careers have been made on the Otto John case,” one intelligence-world observer told me, “but still no one can figure the damned thing out.”

But of all the ambiguities attached to analysis of the meaning of it, none is more fascinating, none more resonant with larger implications than the story John brought back about Kim Philby. According to John, during his marathon interrogation sessions in East Berlin, his KGB inquisitors kept returning to press him on one point in particular: Who was Kim Philby really working for?

Now here lies an absolutely delicious feast of interpretive possibilities. Assuming for the moment that Dr. John was telling the truth, were those questions about Kim Philby motivated by genuine doubt, or did the KGB want the West to think it had doubts? Did they know at the time of the interrogation that Dr. John would return to the West to tell of it? Did they allow him to escape in order to return to tell of it? If they had doubts, what were they based on?

There is convincing evidence in the literature that back in the Forties the KGB had allowed the atom-bomb spies Klaus Fuchs and the Rosenbergs to be captured, even though Philby knew enough to have warned them, in order to prevent a Philby tip-off from throwing suspicion on Philby himself. Would the Soviets have given up such major assets for the sake of someone whose loyalty they were still uncertain of? Or did they suspect Philby had been “turned” during his 1951 interrogations?

The question of Philby’s “turning” or re-turning is a fascinating theme of his mysterious limbo years—the period between his forced retirement in 1951 and his final flight to Moscow in 1963. We know he was employed by one faction of his old colleagues in MI6 as a low-level agent in the Middle East, first based in Cyprus, where there is some evidence he was running agents from the Armenian émigré community out of Cyprus across the Turkish border into Soviet Armenia. Had he been “turned” secretly, and was he being rehabilitated, under the direction of MI6, into major-agent status in order again to entice the attention of the Soviets so that he might infiltrate the KGB apparatus for his British masters?

Bruce Page and his colleagues on the London Sunday Times provide perhaps the best summary of the absolutely astonishing murkiness and complexity of Philby’s role in those limbo years:

There could be every reason for putting a man under suspicion of working for the Russians in contact with them. If he is the Russians’ man they will be unhappy at his demotion from the superb position in Washington and they may feed him some genuine information to help him restore his credit. If he is not their man, they may well think that he is, and act in the exactly same manner, anyway. In fact, in such a situation, the loyalty of the agent is more or less irrelevant to anyone except himself.

Those of you who have been able to follow and appreciate these truly dizzying and delightful ambiguities of the problem of Philby’s loyalty in his Mideast limbo are now qualified to appreciate the curious question of our man’s final flight from Beirut to Moscow in 1963.

It’s there that the ultimate question of his loyalty becomes more than relevant to himself; it becomes crucial to an understanding of the secret history of superpower relations in the past two decades.

The situation is this. It’s summer 1962. Kim Philby’s living in Beirut, where he’s been based for six years, ostensibly operating as a roving Mideast correspondent for the London Observer and the Economist. And, of course, still in the employ of MI6 and in the service of the KGB.

Meanwhile, in Israel in June of that year, an Englishwoman is overheard criticizing Philby’s journalism at a cocktail party. She doesn’t like his pro-Nasser slant, and she’s heard to say that “as usual, Kim is doing what his Russian control tells him. I know that he’s always worked for the Russians.” Swiftly the woman is returned to England. Interrogated. She admits to having befriended Philby after he returned to England from his Vienna wedding to an underground communist bride. She recalls having asked him why he had suddenly taken on the guise of an anticommunist, pro-Franco sympathizer. His reply, she said, was that he was “doing a very dangerous job for peace, working for the Comintern.”

This was enough to make the case against Philby complete. A problem remained: how to get Philby back to England, how to avoid the massive hemorrhage of secrets a public trial would involve. Nicholas Elliot, an old-school-tie colleague in MI6, was dispatched to Beirut to offer Philby complete immunity in return for a complete confession (the same deal that would later be offered to and accepted by Fourth Man Anthony Blunt). Elliot arrived to find Philby expecting him. A tip-off by another, still buried British mole is suspected. But Philby confessed anyway. A limited confession. He asked for more time to decide whether to accept the offer of immunity and return to England to tell all, not just about himself but also about the KGB apparatus that controlled him.

Elliot then flew directly from Beirut to Washington and presented James Angleton, by then CIA chief of counterintelligence, with Philby’s typed confession. And then what happened? For ten days, nothing. And on the tenth day Philby disappeared from Beirut. Six months later he reappeared in Moscow, having once again made a laughingstock of the intelligence services of the West.

There has never been a satisfactory explanation of why Kim Philby was permitted to escape. Not a straightforward explanation, at least.

One British writer suggests it would have been “out of the question to kidnap him back to England.” But even if we accept this kid-gloves approach to a man who betrayed dozens of British agents to their deaths, the notion that the single most effective traitor in British history was given ten days of leisure in which to arrange his escape is difficult to accept.

And where was James Angleton all this time? Think of it: he’s wanted to nail Philby since 1951 and at last his archnemesis is at bay in Beirut, apparently ready to begin to talk. A full confession from Philby could well be the greatest intelligence coup of the postwar era. At last—at least—we would begin to know what the Soviets knew about us and when. At last we might learn how deeply penetrated we had been and perhaps who the Big Mole, the American Philby, was. And yet with all the resources of the CIA at his disposal for the most important mission of his career, Angleton did not even cover Philby with enough surveillance to prevent his slipping out of the city at his convenience and making his way to the safety and comfort of Moscow.

There are only two possible explanations for this phenomenal circumstance. One is that Philby, particularly Philby with a grant of immunity, would have been too much of an embarrassment had he remained in the West and that the clandestine services of both Britain and the U.S. were happy to see him slip away beyond the reach of the press and publicity. (I have also been told by one mole-watcher that there is some suspicion that the Soviets were so worried about Philby’s talking that they removed him from Beirut “at gunpoint.”)

The other possible explanation—curiously, one that does not appear anywhere in the literature I’ve seen—is that sometime in those ten days following his confrontation with Elliot, Philby was “turned.” Turned and encouraged to escape to Moscow—the better to serve those he’d once betrayed. To become our mole in the KGB. A more likely version of this variant would be that Philby convinced the endlessly gullible British that he could be turned and thereby earned himself the ability to make a leisurely and unhampered exit from Beirut and laugh over the whole affair with Andropov when he arrived in Moscow. Still, in this regard the dying words of Guy Burgess cannot be ignored. According to Nigel West’s history of MI5 (A Matter of Trust), Philby’s fellow mole and Moscow exile, Burgess, “on his death-bed, had denounced Philby as a British agent.” Perhaps this was merely one final example of Burgess’s notorious reputation as a prankster. Perhaps Burgess—generally acknowledged to be brilliant and shrewd despite his streak of playful irresponsibility—knew something. He died before he could be interrogated further on this question. Only Kim Philby knows the truth.

What we do know is that the moment Kim Philby arrived in Moscow marked the beginning of a remarkable change in the personality of the KGB. So striking has been the shift in its operational profile that it is impossible not to see in the complex and sophisticated new character of the mind of the KGB the shaping influence of the mind of Kim Philby.

“Contrary to what was believed in the West, Philby was no retired intelligence agent” when he reached Moscow, writes recent Soviet defector Vladimir Sakharov. “In fact, from the moment he arrived in Moscow, he had become an important member of the KGB’s inner circle…. In the process, Philby played a vital role in the rise to power of…. Yuri Andropov…. Simply, Andropov used Philby to tell him how the KGB should look and operate, especially in Western Europe and the United States.”

And what did Philby tell Andropov? Get a new tailor, for one thing. Away with those “ill-fitting suits” so beloved of spy-fiction portraits of Soviet agents. The new, Philbyan KGB began to attire itself in expensively tailored, stylishly cut Western suits, the better to blend into the sophisticated circles of the Western capitals it was assigned to penetrate.

But the Philby signature can be seen in more than surface sophistication: KGB operations—once mainly distinguished by thuggish tactics of blackmail, bribery, and brute force—developed a level of subtlety and complexity almost baroque, in fact rococo, in the many-layered richness of ambiguity they displayed. Particularly in relation to the American target; particularly in relation to James Angleton.

Sakharov notes Philby’s alliance with one Aleksandr Panyushkin, who had served as his control during the crucial years of 1949–1951, when Philby was stationed in Washington, having those long weekly lunches with James Angleton and using their intimacy to steal every secret the U.S. secret services had.

Panyushkin, Sakharov tells us, “eagerly sought Philby’s advice on how to deal with Americans.” And just how did Philby advise the KGB to attack the American target? It’s clear from the history of the next decade that a conscious decision was made to target the mind of James Angleton. The goal: to drive him crazy, destroy his effectiveness as chief guardian of the secrets of the Western world. The method: the double-cross system.

After all, it was Philby who had molded the mind of Angleton when he tutored him in the double-cross system they worked against the Nazis. And it would be Philby, alone among men, who would know exactly how to undo the mind he’d created, using its very double logic to twist his one-time pupil’s mind into a pretzel.

Nowhere in the literature of the mole maze has anyone—until now—seen the utterly devious brilliance of the web Philby wove to entangle Angleton. To see it in its proper perspective, we have to look at five schools of counterintelligence theology that have grown up around the Big Mole question. Yes, theology.

“When you get in this deep,” one of my intelligence-world sources was saying, “all the real questions become theological.”

We had been speaking specifically about the murky nature of the soul of Yuri Nosenko, the maddeningly enigmatic Soviet defector, the locus of whose true loyalty had baffled some of the most brilliant men in American intelligence for a decade. It was a question whose answer might resolve fundamental perplexities of doubt and belief but one that just could not be resolved, it seemed, by means of reason.

Partisans were reduced to a religious faith, skeptics were not so much advancing positions as perpetrating heresies.

And so, as we examine the five schools of thought on the real meaning of the great Mole Hunt, we have to realize that it has become as theological as, say, the sixteenth-century controversies in the Church over transubstantiation versus consubstantiation, the question of the presence of the mole being almost as arcane and inaccessible to mere reason as the question of the nature of the Presence in the Host.

Our first school—let’s call it the Angletonian orthodoxy—believes in the Real Presence of Big Mole as an article of religious faith, the way the Devil is more real to certain true believers than God. Not only does Big Mole exist, but he is a kind of organizing principle of the perceptual phenomena of this world, running the CIA from deep within the structure of the intelligence apparatus, ensconced as ineluctably as original sin at the center of its soul. The Angletonian orthodoxy has its genesis in what might be called the Gospel according to Golitsyn. Anatoly Golitsyn, the first Big Defector from the KGB. You might call him the John the Baptist of Big Mole theology. Although he defected back in December 1961, he remains “even today, by far the most controversial figure in the world of intelligence,” according to Nigel West.

The controversy is not over the number of genuine moles Golitsyn exposed. When he defected from his post as a KGB counterintelligence officer in Helsinki, Golitsyn brought with him the names of a number of KGB penetration agents in England, Western Europe, and Scandinavia. And solid clues that helped make the case against others, including Philby. No, the controversy was over conceptual moles—supposed deep-penetration agents, particularly in America—for whom Golitsyn had only fragmentary clues and code names.

The mole code-named sasha, for instance. The sasha story was the first incarnation of Big Mole, the first shadowy prefigurement that there was a high-level penetration agent in America—inside the CIA headquarters itself. Golitsyn’s gospel tale of the Activation of sasha—which first appeared in Angletonian acolyte Edward Jay Epstein’s groundbreaking book, Legend—was to become the central credo of the True Angletonian Faith:

Washington, 1957. A top KGB official, Viktor Kovshuk, makes an unexpected flight from Moscow to Washington. He slips into town without surveillance and makes some mysterious rendezvous. Flies back almost immediately.

According to Golitsyn, the sole purpose of this unusual round trip was the “activation” of an extremely high-level mole inside the CIA headquarters. Golitsyn didn’t know his real name, he said. Only his code name: sasha. The search for sasha began. It is still going on now, at least in the mind of James Angleton.

Belief in the existence of sasha became in itself a religious test of faith, not only for everyone in the CIA but for every subsequent defector. Those in the CIA who expressed doubts about the existence of sasha immediately came under suspicion of being sasha. For subsequent KGB defectors, failure to stick to the one true sasha story became evidence that one was sent to protect sasha.

Such was the fate that befell Yuri Nosenko when he fell into the hands of the orthodox Angletonian inquisition. If you believe the Angletonians and the Angletonian theologists, Nosenko was the single most devious, most fiendishly clever, most successful spy ever encountered by the great spy hunter of the West.

Nosenko was, according to the orthodox Angletonian gospel, the first of the false prophets Golitsyn had foretold would come to throw doubt on him and question the existence of sasha. And sure enough, not long after Nosenko defected in January 1964, he was telling a story that confused everyone by saying sasha was actually Andrey. Nosenko’s defection was an offer the CIA couldn’t refuse, because Nosenko claimed to be the KGB officer who, in November 1963, was assigned to go through the entire KGB file on one lone American defector, Lee Harvey Oswald. But Nosenko’s Oswald story (Nosenko claimed the files showed no direct KGB involvement with the ex-U-2–base radar operator) was merely a red herring, according to the Angletonians. Nosenko’s real mission was to shield sasha, and during his debriefing he casually let slip a revised version of the Kovshuk activation story designed to discredit belief in sasha’s importance.

According to Nosenko, the real purpose of the 1957 Kovshuk trip was to activate a penetration, but not that of the exalted and mysterious sasha. Nosenko claimed never to have heard of sasha. According to him, Kovshuk had gone to Washington to tend to an agent code-named andrey. He gave enough details of andrey’s identity to lead the FBI to arrest a Sergeant Rhodes, who had once worked in the American embassy motor pool in Moscow. When interrogated, Rhodes admitted meeting with Kovshuk in 1957.

Could this grease monkey be the master mole sasha of the Golitsyn gospel? Or was Nosenko deliberately trying to protect sasha by claiming the Kovshuk mole was really this minor-league andrey—and that he’d already been caught, and the whole mole hunt could be called off?

It was over this question that the first shots in the decade-long Mole War within the intelligence community were fired. It was over this question that a subterranean civil war would be fought inside the CIA, a war for the secret soul of the West, a war that, according to the Angletonian gospel, the good guys lost.

The good guys. Recalling that this is the orthodox Angletonian gospel we are relating here, it’s still hard not to remark that the good guys went a little crazy in the final throes of the Big Mole madness. Particularly over Nosenko. Because everything about Nosenko fit perfectly into the prophecies of Golitsyn: the false prophet sent to cast doubt upon Big Mole’s existence, the false clues he scattered, the false description of himself, the eagerness of other false defectors to declare all he said was true. Everything fit. Except one thing: even after all his falsities had been thrown in his face, Nosenko would not confess. He still claimed to be a sincere defector. He would not break down and say who sent him and why. He would not reveal what he really knew about the identity of Big Mole.

Enter the bank vault. Perhaps the single most horrifying episode in the entire tortuous Mole War chronicle. Not merely tortuous; it was, in fact, nothing less than torture.

When conventional methods of interrogation failed to get Nosenko to confess his perfidy, the Angletonians decided he would have to be convinced of the absolute hopelessness of holding out. And so they put Nosenko in a thick-walled steel cage, with only a single bed and a bare light bulb, nothing to look at, listen to, or react to, no distinction between night and day, no hope of escape except by a confession. They kept him in solitary confinement for two and a half years. There are hints they did more than observe him, interrogate him, and subject him to extreme sensory deprivation. There are hints that they slipped him mind-altering truth-serum drugs. There are hints of harsher, more physical methods brought to bear. And yet, after all that, Nosenko never cracked. Or at least he never yielded up the “truth” that his Angletonian inquisitors were certain he was concealing.

Instead, what happened was that when Nosenko wouldn’t crack the Angletonians began to crack. The counterintelligence inquisition they were conducting began to get out of hand. They demanded that the entire key Soviet Bloc division of the CIA—the single most important sensory apparatus trained on the Soviet Union—be quarantined from all contact with confidential information, for fear of contamination by the invisible presence of Big Mole somewhere in its midst. In effect, they put the CIA out of commission when it came to running operations against its chief target. Then they began to turn on one another. Even Nosenko’s chief inquisitors came under suspicion. One of Angleton’s deputies made a case against a high-ranking fellow CIA officer who had compiled a report proving the falsity of Nosenko’s cover story. In other words, a case was made against him because of his very support of the orthodox Angletonian position. The logic behind this: Nosenko had been sent a false cover story specifically to help promote the career of the man who unmasked its falsity, who would thereby be in an unassailable position to protect the identity of Big Mole.

By August 1966, Nosenko was still in solitary, but the entire anti-Soviet capacity of the CIA was in quarantine, and a subterranean religious schism between the Angletonian believers and the skeptics and agnostics who doubted the existence of Big Mole was tearing the place apart.

At this point the tide began to turn against the Angletonians. At this point, CIA director Richard Helms, seeing his entire agency consuming itself in a cannibalistic civil war, made the classic demand of the organization-minded bureaucrat: resolve the Nosenko case in sixty days one way or another.

This was akin to saying prove or disprove the existence of God within sixty days. It didn’t happen. A pro-Nosenko faction, based in the CIA’s Office of Security, made a case for accepting Nosenko’s story at face value. He had, after all, brought over many valuable clues that had led to the exposure of genuine Soviet penetrations all over the world. Would the KGB have sacrificed that many assets just to give credibility to a defector whose mission may merely have been to protect a so far invisible Big Mole?

Absolutely, the Angletonians argued; the value of the agents and assets sacrificed just indicated the value of the Big Secret that Nosenko was sent to shield.

Sixty days passed, and nothing was really resolved. But Nosenko was removed from the bank vault—just as he was about to crack, the Angletonians claimed.

And from that point on the CIA, indeed the entire anti-Soviet intelligence capacity of the United States, shifted, according to the Angletonian gospel, into the hands of the Soviets, under the invisible guidance of Big Mole—whoever Big Mole might be.

Now there arose in opposition to Angletonian orthodoxy a Second School of thought, what might be called the “sick-think reformation.”

“Sick think.” That was the phrase used to characterize the convoluted, contagious logic of suspicion and paranoia that the Angletonians applied in analyzing the accounts of almost all defectors subsequent to the prophet Golitsyn. “Sick think” was the term used in testimony before the House Assassination Committee to characterize the rationale behind the extended isolation and torture of Nosenko.

In the years that followed Nosenko’s release from the bank vault, the “sick think” view of the Angletonian gospel became the new official orthodoxy in intelligence circles. Nowhere is the case for sick think made more convincingly than in David Martin’s brilliant work of reporting, Wilderness of Mirrors, a work that incensed the Angletonians no end, but which—it might be argued—is a compassionate, even respectful view of a brilliant mind led astray by its own complexity and sensitivity.

Martin creates a convincing portrait of Angleton as a victim of the mirror-image doubleness of his own counterintelligence logic. The key assumption behind the sick-think theory of Angletonian orthodoxy is that Big Mole probably never existed. That Angleton came to worship its existence as a kind of false idol, a Golden Calf created by Angleton’s guru Golitsyn. In fact there is, in the comments Martin elicits from sick-think theorists, a distrust of Golitsyn as a Dostoevskian, Rasputin-like mad monk infecting clear-thinking Americans with dark and murky Slavic speculations; making Americans think like Russians.

Consider, for instance, William Colby’s reaction to hearing the Angletonian gospel: “I spent several long sessions doing my best to follow [Angleton’s] tortuous conspiracy theories,” Colby has written, “about the long arm of the powerful and wily KGB at work, over decades, placing its agents in the heart of Allied and neutral nations and sending its false defectors to influence and undermine American policy. I confess that I couldn’t absorb it, possibly because I did not have the requisite grasp of this labyrinthine subject, possibly because Angleton’s explanation was impossible to follow, or possibly because the evidence just didn’t add up to his conclusions.”

After Colby’s accession to power in late 1973, Angleton gradually became isolated in an agency that was seeking to purge itself of a murky and tainted past and that saw “sick think” as a symptom, a symbol of those dark ages. But increasing isolation did not deter Angleton from pursuing Big Mole or discovering even Bigger Moles.

Project Dinosaur, first revealed by David Martin, is probably the most shocking example of the extent of the distrust engendered by the Angletonian orthodoxy. Project Dinosaur was the code name for Angleton’s attempt to prove that perhaps the single most respected figure in the American diplomatic establishment, Averell Harriman, was in fact a longterm Soviet mole.

Once again, the origin of this suspicion was an apocryphal tale from the Golitsyn gospel. Golitsyn claimed the Soviets had recruited a powerful member of the American establishment as a long-term agent in the Thirties, and on his return to the Soviet Union in the Fifties had commissioned a play dedicated to him. The plot involves the illegitimate son fathered in the Soviet Union in the Thirties by a capitalist prince, who then is reunited with his American father in Soviet solidarity in the Fifties. Now there is some controversy as to the identity of the capitalist. In Martin’s Wilderness of Mirrors he’s clearly identified as Harriman. However, a prominent Angletonian partisan confided to me that he thought the play was really about U.S. merchant prince and Soviet friend _ _ _ _ _ _.

In 1974 the end came for Angleton and for the first phase of the mole war. Colby had appointed one of Angleton’s Big Mole suspects to be CIA station chief in Paris. The man had been cleared of all suspicion—by all but the diehard Angletonians—but nonetheless Angleton flew to Paris, buttonholed the head of the French counterespionage department, and warned him that the CIA had placed a Soviet mole in his capital city.

When Colby found that out, he fired Angleton. He disguised it by confirming a leak to Seymour Hersh that linked Angleton to an illegal mail-interception program. But the real reason for the firing was his inability to get Angleton off the mad mole hunt.

Soon afterward, Colby’s CIA not only rehabilitated Nosenko’s reputation and gave him back pay for the time he spent in the bank vault, they even set him up as a paid consultant teaching counterintelligence—Angleton’s job—to new recruits.

To the Angletonians, it was a complete coup. A Soviet agent was now shaping CIA counterintelligence operations. There were murmurings from the Angletonians about Colby’s own loyalties. There was talk of a liaison Colby had had in Vietnam with a French journalist suspected of being KGB-controlled, which Colby had not officially reported on. Some were quoted as saying that, considering what Colby was doing to the agency, he “might as well be a Soviet Mole.” There were scores of resignations and forced retirements from the ranks of the Angletonian loyalists. It was nothing less than a purge. A purge that left the agency in the control of the Big Mole, if you believe the Angletonians. In defeat, they said, the Nosenko case had “turned the CIA inside out.”

Still, the struggle did not end there for the Angletonians. The struggle is going on now. In the years since his dismissal, Angleton himself has been officially silent, but his acolytes have been generating a steady stream of fiction and nonfiction books that have brought the story of the subterranean civil war to the surface and popularized the Angletonian gospel. First and most importantly there was Legend, Edward Jay Epstein’s study of the strange career of Lee Harvey Oswald, which was really the story of the Nosenko controversy, which was really the story of Angleton’s search for the Big Mole.

Then there was Mole, by William Hood, one of Angleton’s deputies in the counterintelligence department. Mole is ostensibly the story of the ill-starred career of one of our moles in Moscow in the late 1950s, a Colonel Popov. But the subtext of Mole is that all the ambiguities of the case seem to add up to a conclusion that our mole was “blown” by one of their moles on our side, and once again we are given the Angletonian gospel about the tragic failure of the bumbling CIA bureaucracy to listen to the warnings of Angleton and his staff about penetrations.

And then there is Shadrin, by Henry Hurt, a fascinating account of perhaps the most complex, baroque, almost “overartfully sculpted” (as one CIA officer called it) KGB deception operation. The target of the operation was Nikolai Shadrin, a onetime Soviet destroyer commander who defected to the U.S. in 1959. Six years later, a KGB officer known as “Igor” offered his services as mole to our side. “Igor” told the CIA that if they helped promote his career he’d quickly rise to a top post in Moscow, where he’d funnel a feast of Soviet secrets direct to us. Exactly how should we help him gain this promotion? We should make it seem that he’d recruited Shadrin back to the Soviet side, and have Shadrin (who was then a Defense Intelligence Agency employee) feed him U.S. military information to turn over to the KGB.

According to Henry Hurt, Angleton saw through this immediately as a KGB “provocation,” an attempt to seduce or abduct Shadrin back to the U.S.S.R. Angleton encouraged Shadrin to go ahead and meet with Igor, feed him doctored data and disinformation, but warned him never to meet with Igor outside North America. At that point it seemed as if Angleton had turned the devious Shadrin game to our advantage.

But at that point Angleton was fired. The people who believed that Angletonian thinking was “too convoluted” took over the agency, people who began to think that “Igor” was a real find, a high-level KGB agent who might end up working for us in the Kremlin. And so when Igor insisted that Shadrin fly to Vienna to meet with him, objections were raised by holdover Angletonians who feared the worst. But the new regime was so eager to please Igor that they told Shadrin to go ahead. Shadrin left his hotel room in Vienna one night in 1977 for a scheduled rendezvous with Igor. He never returned. The Angletonians are certain he was kidnapped, tortured, and probably executed by the Soviets as an example to those tempted to defect in the future. A victim of those on our side who failed to heed the warnings of the Angletonians.

If at the heart of the sick-think reformation was the belief that Angletonian orthodoxy was too convoluted, the essence of a Third School, a school of which I am, so far as I am aware, the sole proponent, is that James Angleton’s thought was not convoluted enough. That he was one convolution short of the dazzling complexity of the mind of Kim Philby. That Philby, Angleton’s tutor in the double-cross system during the Second World War, simply—or complexly—outsmarted Angleton with a game that might be called the double-double-cross system, a game that depended on the creation of Ghostly Presences that I would choose to call Notional Moles.

To explain the notion of notional moles, let me cite two examples from historian John Masterman’s study The Double-Cross System: plan stiff and plan paprika.

Now the basic method of the double-cross system evolved when the British secret service captured German spies in England during wartime. The spies were quickly “turned,” on pain of execution, and forced to send back on their radio transmitters whatever disinformation the British wanted German intelligence to believe. Frequently the German spies, while locked in London prison cells, would be given “notional” adventures to report back to their German superiors. The term notional comes from medieval philosophy, and refers to the class of entities that exist only in the mind.

And so, for instance, Masterman describes the “notional” activities of captured Nazi spy snow and his captured spy ring associates summer and biscuit. “On 17 September 1940, snow dispatched biscuit, who met summer …. He then notionally took summer with him to London …. The Germans were told via snow’s transmitter that summer had fallen ill … and was being nursed by biscuit ….” (My emphasis.) All of these notional adventures are taking place while the actual agents are in jail.

The notional method, Masterman tells us, was also used to create the specter of British moles within German territory, plan stiff, for instance. “This plan was to drop by parachute in Germany a wireless set, instructions and codes, and to persuade the Germans that an agent had been dropped but had abandoned his task. It was hoped that the Germans would have to undertake a search for the missing agent ….”

And even more resonant for the American mole-hunt question is plan paprika, which was, according to Masterman, “evolved in order to cause friction among the German hierarchy in Belgium. A long series of wireless messages was constructed containing sufficient indications in code names and the like to allow the Germans to guess which of these high officials were engaged in a plot to make contact with certain British persons with a view to peace negotiations.” (My emphasis.) In other words, to inspire a Nazi mole hunt.

Plan paprika was aimed at creating “notional” traitors, whose conceptual existence would do as much or more harm than real traitors because of the unresolvable suspicion, distrust, and dissension the hunt for the nonexistent notionals would cause among the very real objects of suspicion created thereby.

The advantage of “notional” moles, of course, is that the side employing them doesn’t need any real recruits, any long-term cultivation of ideological dissidents, or blackmail to recruit someone within an opponent’s intelligence establishment. In fact one is better off without a real mole.

Now, imagine you are Kim Philby and you are facing an ultrasuspicious James Angleton across the chessboard in the game of East-West deception. How do you put one over on an opponent who knows you’re out to put one over on him?

Assume that your goal has two parts: to neutralize or destroy the effectiveness of counterespionage against your side, and to get inside the secret files of the other side. Now let’s make it harder. Let’s assume you have no “assets,” as they say, on the other side. You have no real mole, no big mole, no little mole already there to help you out. How do you start?

First, let’s get into the files. Let’s get deep into the most intimate personnel files of the CIA with the psychological profiles of the most secret of secret agents and their case officers, the ones who might be running moles against us. How? Let’s send over one of our most brilliant agents, let’s call him X. Let’s give him the names of some of our genuine moles in other nato countries. We’ll have to make some sacrifices here, blow some people who have been pretty valuable, but look at the prize: the Central Registry of the CIA’s Soviet Bloc division. So we’ll let X expose some nato moles and then we’ll provide him with a bombshell of a clue. To an American mole. One we know doesn’t exist. But they don’t. A “notional” mole. We’ll have X insist he can’t even speak of this clue to anyone but James Angleton and the president of the United States. Everyone else is suspect. And here’s what he’ll say: “You people have been penetrated. Someone very high up is a KGB agent. My buddies back at Dzerzhinsky Square are so full of themselves over this that they get a little loose in the tongue. I’ve heard bits and pieces. Some clues. If only I could match them against your files ….”

At this point you’ve got Angleton in your hip pocket. You’ve confirmed all his darkest suspicions about the complete penetration of every other secret service in the West. And now you’ve got him on the track of the biggest prize of all: the Big Mole within his own organization. You begin to dredge up certain suggestive details from your tour of duty at KGB headquarters, a first initial, a career path, a peculiar operational signature ….

And then Angleton makes a suggestion. Why don’t I let you look through our personnel files, study the details of some of the most important cases, the moles we’ve run against Moscow? And there you are. All the way in. Certain American CIA execs are horrified at the idea of letting a senior KGB officer—defector or not—get into those files, but that only suggests they have something to hide in there. And so in three years you’ve accomplished all that it took three decades for Kim Philby to achieve: total access to the secret soul of the Western intelligence services.

But that’s not enough. Not if you’re Kim Philby and your target is James Angleton. Sure, you know his files inside out now, but you want something more: you want to destroy his effectiveness for the future. Forever. You want to paralyze the entire Central Intelligence Agency. So you think back to the first time you met Angleton and the two of you worked together. The double-cross system. You taught it to him. How to make the enemy believe false information is true by putting it in the mouths of false defectors you’ve turned to work for you. You know Angleton will see right through a simple disinformation operation so you’ve got to give it one further twist.

You’ve got the mole hunt going, but the question is: how to keep it going? Since there is no big mole, sooner or later one suspect after another will be cleared of false suspicion and questions will be asked about the validity of the original mole-hunt clue.

How to do it? What about making it seem that your notional mole’s masters are panicked at the progress of the mole hunt, that they fear Big Mole’s exposure, and have mounted a complex diversion operation to protect his notional cover?

Enter the false defectors. A delicate game here. Their falsity has to be exquisitely, carefully calibrated with an eye toward congruence with the rhythms and counterpoints of Angletonian counterintelligence theory.

So you send one false defector after another to approach the CIA. You provide them with some true information and some false, and one common theme: there is no Big Mole, there were a few little moles, but they’ve already been caught.

You know that with Angleton’s double-cross-system mentality he’s going to say to himself: if they’ve sent over a false defector to say there is no big mole, then there must really be a Big Mole they’re trying to protect. But if you make it too easy to detect the falsity of the defector, if you don’t provide him with enough true material to show that you deem the Big Lie about Big Mole important enough to sacrifice some valuable medium-size truths, then Angleton might see through the game, see that at bottom you want him to believe there is a Big Mole and therefore the reality might be that there is not.

And it is precisely here that Angleton’s mind failed to be convoluted enough. He was too obsessed with the certainty that a betrayal had occurred and thus blinded to the possibility that this was exactly what Philby wanted him to think. Of course, if Angleton had followed this logic he would have to distrust any conclusion he came to as the one Kim Philby wanted him to make. Which would have been the abandonment of reason to an assumption of Philbyan omnipotence. But in fact he ended up abandoning reason anyway—to an irrational faith in the existence of, the omnipotence of, the unseen presence of Big Mole, a presence that now seems just another notional conjuration by the master of double double cross, Kim Philby.

The surprising thing about this is that Angleton himself didn’t grasp the possibility that he was the victim of a notional-mole ploy, that his thinking didn’t take that one final convolution, particularly when he knew it was Kim Philby he was facing across this conceptual chessboard.

The inability to believe that Angleton could have been so thoroughly outsmarted is probably the genesis for the fourth and most shocking and improbable of all the mole-theory heresies: the notion that Angleton himself is the Big Mole.

There’s a certain insane logic to it if you choose to sit still for it. Angleton’s renowned obsession with Big Mole, his finger-pointing at practically everyone else in the agency, can now be seen as the perfect cover for a malevolent mole masquerade of his own. And the effect of the Angleton-inspired mole hunt was easily as destructive of the CIA as any mere information-gathering mole might be.

Angleton a Soviet mole? The possibility is as astonishing and unbelievable as the notion that Philby was a mole before 1951. Or that Philby might be our mole even now.

But it was a man on Angleton’s own counterintelligence staff who made the case against Angleton. And not a dreamy novice; no, it was Clare Petty, a case-hardened counterintelligence officer who’d earned a reputation for shrewdness when he was the first to spot the top mole in the West German BND, Heinze Felfe, long before the Germans caught on to him.

What little we know of this bizarre heresy again comes to us from David Martin’s Wilderness of Mirrors, although the fact of the allegation’s existence—if not its credibility—has been confirmed by attacks on Petty from the Angletonian camp, perhaps inspired by information coming from Angleton himself.

In June 1974, according to Martin, Clare Petty delivered to his superior a massive report on Angleton’s career. There were boxes of documents and twenty-four hours of tape recordings to support the allegation, but all of the evidence was said to be “circumstantial.” And even some of the circumstantial evidence was tenuous at best.

One instance cited, for example, was Angleton’s failure to follow up a Soviet defector’s allegation that Henry Kissinger was a long-term Soviet mole. The allegation came from a defector named Goleniewski, who had exposed some genuine penetrations in Western Europe but whose credibility had subsequently been damaged by his repeated claim to be true heir to the throne of the Romanov tsars.

The case against Angleton was in a sense a displaced case against his guru Golitsyn, the defector whose mole warning had created the whole mole madness, the KGB agent whom Angleton had allowed to burrow into the most secret and sensitive CIA personnel files, ostensibly in search of mole clues. “How the hell,” Martin quotes one CIA division head as saying, “could anyone in his right mind give a KGB officer enough information [from CIA files] to make a valid analysis?” The Great Mole Hunt these two conducted had, one might argue, done more to destroy the effectiveness of the CIA than any ten highly placed moles might have accomplished. But the question remains: if this utterly improbable thesis were true, when might Angleton have been recruited? And why? It is here that we must return to the perplexing question raised by the Corson footnote and the Teddy Kollek tip-off—just what was the “deeper game” Angleton was playing with Philby’s Ring of Five? Why was he running it from so deep in his hip pocket? Just what was really being transacted between Angleton and Philby during those two years of long weekly lunches they shared at Harvey’s restaurant in Washington, D.C.?

Of course, there is a fifth permutation of these possibilities. Some might call it even more farfetched than the Angleton-as-mole heresy. What if the truth were not that Philby was running Angleton but that Angleton was running Philby? That Philby and even his KGB soul mate Andropov were our men in Moscow?

Wait, you say. How could that be? Angleton has been fired, exiled, and dismissed from intelligence work. Furthermore, Angleton and the Angletonians are constantly proclaiming the defeats that the KGB has inflicted on U.S. intelligence. The Angletonian gospel insists that the brilliance of the KGB and the foolishness of the CIA ruling establishment have created disaster after disaster for our side, that it’s practically run by the KGB.

But look at it another way. What if Philby was our man in Moscow? Wouldn’t we want his KGB associates to think he’d been a brilliant success, that he had even their archnemesis James Angleton on the run, that they’d dealt us grievous defeat after grievous defeat? Wouldn’t we want the Soviet presidium to think that Yuri Andropov had been a masterful general in the complex war of moles and disinformation?

Of course, it would require a massive deception operation on our part to create such an impression. Many events—the firing of Angleton, for instance—would have to be staged. The Soviets would have to be convinced that we were convinced we’d been utterly defeated in the mole wars. Entire factitious histories would have to be created, which would mean that much of the orthodox Angletonian literature would, wittingly or unwittingly, have to reflect the strategy of the grand deception.

Is such a thing possible? I admit I wouldn’t have considered it if I hadn’t come across two particularly provocative passages in mole-war literature.

The first appears in what seems at first to be an utterly dry and academic analysis of disinformation theory. It’s an ostensibly idle flight of speculation in a paper entitled “Incorporating Analysis of Foreign Governments’ Deception into the U.S. Analytic System.” The paper was delivered to a Washington symposium sponsored by a little-known group called the “Consortium for the Study of Intelligence,” and published in an obscure volume called Intelligence Requirements for the 1980’s: Analysis and Estimates.

The author, however, is not obscure. He’s Edward Jay Epstein, perhaps the premier journalist in the mole-war field. As we noted earlier, Epstein’s book Legend was the first to expose the subterranean civil war within the CIA over Big Mole and to make the Angletonian case that the agency had been subverted and defeated by the intrigue of KGB-sent false defectors.

The paper in question, however, has little of the undercover exposé glamour of Legend. It focuses on an abstract and academic analysis of the “bimodal approach” to analysis of deception and disinformation techniques. The paper makes a useful distinction between “Type A Deception,” which Epstein defines as “inducing an adversary to miscount or mismeasure an observable set of signals” (the British, for instance, placing dummy aircraft on Scottish runways during World War II in order to scare the Germans into thinking an Allied invasion of Norway instead of Normandy was approaching), and “Type B Deception.”

The latter is the most fascinating and complex mode. It aims, says Epstein, at “distorting the interpretation or meaning of a pattern of data, rather than the observable data itself.

“The main component of Type B deception,” Epstein suggests, is generally “disinformation which purports to emanate from the highest levels of decision making: for essentially it must be represented as reflecting the secret strategy and motives of those in command. Such supposedly high-level information must be passed either through a double agent or a compromised channel of communication…. The disinformation can be plausibly reinforced by statements to diplomats, journalists and other quasi-public sources” (my italics).

While Epstein’s paper is purportedly about the importance of acquiring a capacity to analyze and detect the possibility of Type B Deceptions being used on us, his discussions of the requirements for Type B Deception analysis apply also to the capacity for performing Type B Deceptions on an enemy. He goes on to propose the creation of a separate Type B Deception team for the purpose, he says, of analysis, but with the obvious capacity for perpetrating grand deceptions.

“This unit,” Epstein suggests with remarkable confidence, almost as if he were describing something that already existed, “would be capable of generating a wide range of alternative explanations for received information.”

While Epstein makes it sound like a mere analytic unit, his suggestions as to the kind of personnel to be employed make it obvious that we are talking about an offensive disinformation capacity: “It might conceivably employ functional paranoids, confidence men, magicians, film scenarists, or whomever else seemed appropriate to simulate whatever deception plots seemed plausible.”

Simulate or stimulate deception plots? The importance he attaches to such a unit makes it hard to imagine we don’t already have this capacity. And without seeming like a functional paranoid it’s possible to imagine it has already been used. Perhaps in the service of the grandest, most imaginative high-stakes Type B deception ever attempted: the running of Kim Philby and the placement of our mole Yuri Andropov in the ruling seat in the Kremlin.

In other words, it may not be out of the question to speculate that the whole dark Angletonian gospel of defeats—including, wittingly or unwittingly, Epstein’s Legend—may itself be a “legend,” a cover story, a grand Type B deception to preserve the security of an incredible Angletonian victory.

Hard to believe. But to work, such a deception would have to make one think it’s impossible to believe. And there is one fascinating further piece of evidence for the fifth or Grand Type B Deception Theory: The Hargrave Deception. A novel by E. Howard Hunt. His most recent one. A fascinating piece of work. In previous novels, Hunt has let drop little tidbits of inside agency gossip. The Berlin Ending, for instance, reflected the widespread intelligence-world belief that Willy Brandt was a Soviet-controlled agent.

But the Hargrave Deception goes further. It’s the whole mole story, the whole Philby-Angleton relationship subtly disguised and with an astonishing twist. The James Angleton figure in the novel is called Peyton James, and he’s an angler, a fly-fishing specialist like James Angleton. The Philby type is Roger Hargrave, here an American, but an American educated at Oxford. Without getting into the convolutions of plot, the bottom line is this: the Philby type defects to the Soviet Union for the purpose of infiltrating the KGB. He’s our fake defector, our mole in the Kremlin. The problem is that only one man knows the real nature of his mission (everyone else considers him a traitor). The one who knows, Peyton James, eventually betrays his Philbyesque source—which in a sense Angleton may have done through the hints that have appeared in the Corson footnote. The ultimate double, double, double cross.

Of course, you could say this is all a Howard Hunt fantasy. But so was Watergate.

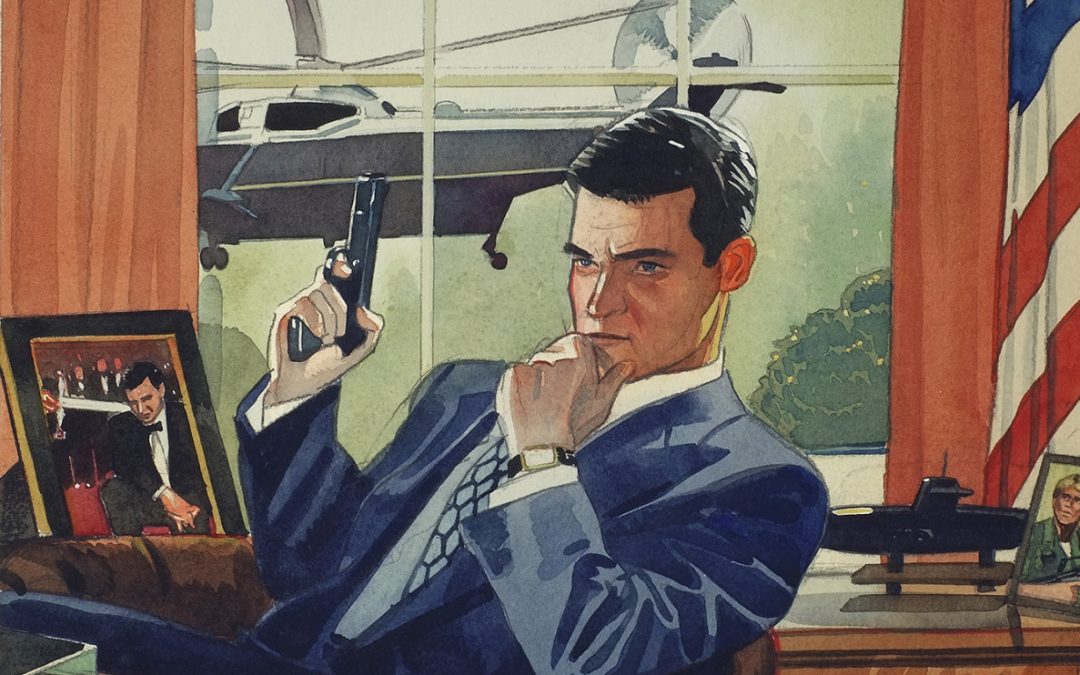

[Illustration by Julian Allen]