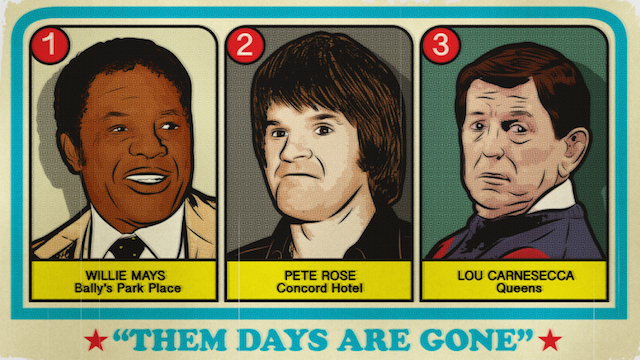

In Atlantic City, Willie Mays played an elderly game, serving as designated greeter at Bally’s Park Place Hotel. After the fracas of his hiring, when Bowie Kuhn barred him from baseball, he settled into a gentle routine of shaking hands, posing for photographs, smiling on request. At $100,000 a year, 10 days a month, he labored without protest. “I survive,” he said.

At two in the afternoon, the casino was a vast space capsule, adrift in limbo. Hunched over their chips, the punters were wedged almost solid, an army of untiring drones, their faces like well-kept graves. This was a place where old smiles came to die.

Though he lived here one week in three, Mays had left his room untouched. No pictures, no gadgets, no books or magazines. Not even a memento, a family portrait. The only sign of his residence was a set of Ram golf clubs, stashed in an open closet.

When he opened his door his eyes were still foggy with sleep. He had a bad cold, and his mouth was filled with stitches, the legacies of yesterday’s dental surgery. Yet he did not sulk; showed no spikes. He was merely indifferent. “Whatever makes sense,” he said.

He was dressed in a bathrobe and pajama bottoms tucked into a pair of athletic socks. Underneath, his silhouette was shapeless, his torso slack. But overall the impression was still of superhuman power. Even in repose, slumped passive on the sofa, great coils and slabs of muscles came to life each time he stirred. Forget the sweat socks, the gut—in his 50th year, in the set of his shoulders and head, the massive force of forearms and hands, the man remained Olympian.

Only one crucial thing was missing. Perhaps because of his surgery, perhaps some deeper cause, his mouth could not form a grin. When a joke was made he raised his upper lip, flexing the lefthand corner. But there was no flash of teeth, and he did not laugh. In the ’50s, when Willie was brand new and the Giants still worked in New York, his smile had been his trademark. Now it was paralyzed.

He felt maltreated. Bowie Kuhn had used him as a scapegoat. Yet he did not gamble himself; had done nothing wrong. Baseball was where he belonged, and this exile made no sense. Still, he was too proud to beg.

The way he described it, his duties with Bally were undemanding but drab. When he wasn’t shaking hands in the casino, he visited schools and hospitals, addressed Kiwanis Clubs, appeared at benefits and parades, played golf with favored clients. The purpose was simply to boost the hotel’s good name. And it needed all the boosting it could buy. Ties to organized crime were alleged. There was opposition to the renewal of the casino’s license. So Willie Mays helped out. The fact that he played in charity basketball games or donated athletic equipment to hospitals—in Bally’s name—did not hush the fuss. Just the same, it did no harm.

In between his stints in Atlantic City, he did business elsewhere and sometimes went home to California, where he owned a house outside San Francisco with two and a half acres of garden, a swimming pool, a whole lot of flowers. His wife supervised the inside of the house. But it needed a man for outside, and he kept going away. It was hard on his wife, hard on him. But he had no choice. The money was always someplace else.

Apart from the Park Place, he kept his dealings private. His income was his own affair. But he worked with Colgate-Palmolive, the Ogden Food Service Corporation, others. Helped with promotion, met with clients. Other times he attended functions. Most of the people he dealt with were very nice, a pleasure to work with. They treated him right. They had respect.

The other sort he ignored.

In certain athletes, the image of their youth is so strong it can never be overlaid. They go on performing for years. They may even remain champions. But the longer they hang on, the more cruel their ultimate comeuppance.

The thing he liked best in business was that it worked the same as baseball. In both, the basic secret was anticipation. When the Giants moved to Candlestick Park, for example, he’d had to adjust the whole way he patrolled centerfield. On a fly ball, he would count to five before moving, then take just a couple of steps, and the ball would drift back on the wind, straight into his glove. Automatic. Because he knew. And business was the same. All you had to do was be prepared, see ahead. The rest was routine.

Put that way, it sounded simple. But it had been financial problems, bad business ventures, that had cornered him in the ’60s and forced him to play too long. The last seven years of his career, he was no longer Willie Mays. The finish had been abject: “I was too old to hit the ball and I couldn’t understand why I couldn’t play anymore. I didn’t understand what was happening to me.”

Muhammad Ali would have understood. In certain athletes, the image of their youth is so strong it can never be overlaid. They go on performing for years. They may even remain champions. But the longer they hang on, the more cruel their ultimate comeuppance.

In Mays’ case, the irony is that the image, the whole Say Hey persona, was basically an illusion. “Nobody ever knew me. The way I really was,” he said. “I started out so scared. I always was a loner, and I kept myself to myself. The only time I felt loose was when I was playing ball. So I’d try to put on a show. Then they started to make it a big deal, the basket catches, my cap flying off, all that stuff, so I sort of tagged along. I gave the people what they wanted. But that don’t mean it was me.”

Nonetheless, Say Hey had ruled his career. All the central elements in his myth derived from the same source: Willie playing stickball in the Harlem streets, a three-sewer man, while the cops shut off the block; Willie soaring, catching, whirling, firing, all in the same motion; Willie stealing; Willie sliding; Willie waving to the bleachers, cap in hand; and Willie grinning, always grinning.

People said he had grown moody, difficult, but they didn’t understand. All his life he had played ball. Now he was outside.

The reality, of course, was something else. Instead of a black Huck Finn, he was a professional, a ballplayer doing his job. From the age of six, growing up in Alabama, baseball had been a career. His father had played for the Birmingham Black Barons; Willie followed automatically. At 15, he worked for a week as a dishwasher in a cafe. This cured him of digression. In 1950 he signed with the Giants for $6,000, solid money then. After that, he never again played for free. Baseball was his release. Wealth was its reward.

Once he had become a star, he lived like one. He kept aloof from his teammates, insisted on his own room on trips. The Giants moved to San Francisco. His first marriage failed. He bought a big house.

After he left New York, nothing worked quite right. San Francisco was not a fanatical baseball town. People didn’t recognize him on the street; kids did not flock around him. He declined from genius to excellence, then to mere competence. When he ran, his cap no longer flew off. He earned the money he was paid, nothing more. In the end, he was traded to the Mets, making $165,000 over two years. His reflexes were shot, and his body did not feel like his own. He fell down under a fly ball. At 42, after 22 years in the major leagues, he retired.

For two years afterward, he mourned, could not adjust. He dabbled in business, worked part-time for the Mets. People said he had grown moody, difficult, but they didn’t understand. All his life he had played ball. Now he was outside. It was not the game itself he missed. After all those seasons, his body was sick of running, chasing, sliding. Once retired, it didn’t even care to jog, or do morning sit ups. “Them days are gone,” Mays said.

But the baseball life, that was something else. He had never let himself form bonds with other players, in case they might get traded, and then he’d have to beat them. Still, he missed the daily rituals.

In due course, 1979, he made the Hall of Fame. He had totaled 2,992 games, 660 homers, 3,283 hits, 338 stolen bases and a .302 lifetime average. He said he was the best player he’d ever seen. Nobody argued.

Nine months later, he took the job with Bally and Bowie Kuhn ejected him from his own game. When the next spring training came around, he wasn’t there, for the first time in nearly 30 years. The last link was severed. He was another retired player.

He did not complain. At times, he suffered from nervous tension. He needed a lot of rest. His best days were spent asleep in his room. Sometimes the demands on his attention, the endless rounds of posing and shaking hands, interminable reminiscences of the Vic Wertz catch made him snappish. But he was handsomely rewarded. On balance, he had no gripes. As he talked, his phone rang. A radio station in Chicago asked him to comment on the Kuhn-DeBartolo imbroglio, re the White Sox. But Willie refused to be trapped. “I have nothing against the commissioner,” he said. “He is the official voice of baseball. Therefore his word must stand, whether right or wrong. Baseball has been my life. I would never say anything to hurt or damage it. If you want some statement like that, why don’t you call Hank Aaron?”

Other requests came in. A salesman wanted Willie to pay for some baseballs he’d been given. A publicist reminded him of a benefit basketball game. Mays handled the demands with resignation. In between, he talked about a young boy he’d been visiting in the hospital, a 10-year-old who had leukemia. Willie had taken him some Frank Sinatra records. The child was eating fried chicken and had seemed to be recovering. A couple of days later, he was dead. Willie had been shocked. He’d felt inadequate. Almost as an afterthought, he mentioned that his own son had also had leukemia, a few years back. But he was better now. He had been spared.

Whatever the subject, his manner remained mild. He was a decent man, being polite. But one sensed profound exhaustion. He spoke of the best technique for stealing bases in Candlestick Park; of living without baseball; of keeping up his garden; of how he could always pay half-price in certain New York stores. All subjects flowed alike. None weighed more than another. Visiting juveniles in jail or frolicking with high rollers—both tired him equally.

At three o’clock in the afternoon, the interview over, he shook hands one more time. Then he went back to bed. “Whatever makes sense,” he said, in his favorite refrain. But he never once said Hey.

How do I live through the off-season?” said Pete Rose. “I rest up. Sleep. Watch sports on TV. Don’t think about age. And count down the days to spring training.”

He also guested at the Concord Hotel. Up in the Catskills, over Thanksgiving weekend, the roads were enveloped in a blanket of sleet, ice, mist. Outside the hotel gates there was a placard for Lefty’s Diner, with the slogan: “O, what foods these morsels be!” Inside, Charlie Hustle engaged in a baseball forum. The Concord was the very hub of the Borscht Belt. It looked like a kosher Colditz, where the sentence was ritual fun. There were game rooms, and card rooms, exercise groups, 24-hour tennis courts and swimming pools, aerobic-dance classes, après-ski parties, tiny tots’ discos and Mr. Jiggs, the chimp. Isabelle Goldfarb taught floral arrangement while Gene Zwellinger pronounced on Investments in a Changing World (Part 1). In the men’s room, a graffito read: “Amy Gitlitz Eats Bacon Strips”; in the Curtain Bar, two grandmothers in hot pants arm wrestled.

Upstairs in the restaurant, Rose stuck out like a suckling pig at a bar mitzvah. Expressionless, he gazed out across the room, over fields of chopped liver and potato knishes, lox and gefilte fish. He contemplated the elders with their paunches, the daughters in their sausage-skin jeans. “A lot of money,” he said.

Physically, he was daunting. On the field, or translated by TV, he merely bulged and strutted like Bluto; in person, he expanded to a post-spinachial Popeye. His chest exploded through his white turtleneck, and his trouser seams strained and gapped, stretched to bursting by his thighs, his heroic rump. Colliding with him full tilt would be like hitting a rubberized wall, a human trampoline that hurled one backward, catapulted into space, like a Bozo shot from a cannon.

Weakness had no place. Nothing about him—his unflinching stare, his certainty of gesture, even the remorseless style in which he devoured his lunch—allowed of compromise. Intimidating, brash, overflowing with self-belief, his presence was just like his game. “What you see is what you get. Nothing more, never less,” explained the Concord’s publicist. Or, as Rose himself might say: “Money talks, bullshit walks.” Facing him was like flashing back to high school. In memory, there was a miniature Rose in every class: the strongest, loudest, most extroverted; the most cynical and most innocent. The ones who had no doubts, and no growing pains. Unlike others, they handled sex without fear, never lost a fight, seemed immune to humiliation. Instinctively, they knew what suited them. No need to fuss with metaphysics or the future of the planet. For them, nothing mattered unless you could touch it. When they found what they really wanted, they grabbed it, and sought no further. Once formed, they never changed.

“You have to keep on producing. Everything you do in public, you’re performing. You can’t ever stop. Not even to take a crap.”

Why was he here? Because the Concord was a showcase for major league ballplayers, a standard part of their winter circuit, and also because it paid. In addition, it guaranteed him attention. Fans came at him nonstop, beseeching autographs. Obliging, Rose inscribed both the P and the R with a prodigious flourish, like heraldic emblems. When he spoke, he raced like a runaway train; when he walked, he charged. Even out of season, he never ceased to compete. “Creating success is tough. But keeping it is tougher,” he said. “You have to keep on producing. Everything you do in public, you’re performing. You can’t ever stop. Not even to take a crap.”

In honesty, what he really wanted to do was to watch Penn State and Pittsburgh play football on TV. He had Penn State with the points, but the set didn’t work. So he submitted to being interviewed. He performed. Answers spooled out like a telex. No hesitations, no mumbled likes or you knows: The street-wit was sharp, the judgments shrewd; the defenses unbreachable.

The secret was single-mindedness. Baseball was what he loved, what he knew, and everything else, except perhaps for money, was superfluous. He had disciplined himself to block out all abstractions, any thoughts that might weaken him or make him vulnerable. “Do I think about passing time, getting older? Why should I?” he asked. “People keep saying my average slumped by 49 points last season, I must be slowing down. But the whole National League was slumping. I still led the league in doubles, came fifth in runs scored, got on base over 250 times. Also, a lot of the time I was batting second, moving a runner across. That doesn’t show in the boxscores. Neither does hustle, or leadership. To myself, I had a solid year.”

He did not brag. Every point was backed up by figures, facts. Other players might crack under pressure. Problems like his—divorce, a paternity suit, wrangling over children—might warp their dedication. But Rose could shut it all out, impervious behind his stats. “Sure, I get bothered. But I don’t get worried,” he said. “Phillies’ fans don’t pay to watch my soul. They come to see me perform, and I better deliver.”

Even so, he was vaguely troubled by the recent eclipse of Roberto Duran. Just a few days before, if one had conducted a poll, Duran and Rose would probably have been voted the most indomitable of all world-class athletes, the two least likely to fall apart. Now one had crumpled. “Imagine that I’m coming up to bat, seventh game of the World Series, bases loaded, winning run on third, and I say, ‘I quit. I won’t hit,’ ” Rose said. “I’d go back in the dugout and shoot myself. I’d have to. Maybe Duran will have to, too. A situation like that, how could a man live with himself?”

Not a pleasant vision. But he cast it aside with a shrug. Nothing like that could happen, not to him. “Fear strikes out,” he quoted. “Running scared never won World Series rings, or made you MVP.”

“Sports today is a business. Our whole society’s a business. So sports just echoes the trend. Of course, the fans don’t like that. They want ballgames to be an escape, a fantasy. But you have to be realistic.”

Baseball apart, his other great passion was wealth. After the Series, he had toured Japan. The owners were lining up for him with suitcases stuffed full of cash. The Kobe was delicious—you could cut it with a fork—but the prices were sky-high. Raw fish with the heads on were cheaper, but he wished they would keep still.

When he retired, he would probably try managing, even though the salaries weren’t much. Not that he was trying to take away Dallas Green’s job. But he’d be at the ballpark every night regardless, so he might as well be employed. After all, if he had a job, he wouldn’t have to pay to get in.

By the same token, his love of baseball itself, though genuine and all-consuming, also had its pragmatic side: “Sports today is a business. Our whole society’s a business. So sports just echoes the trend. Of course, the fans don’t like that. They want ballgames to be an escape, a fantasy. But you have to be realistic. Say I woke up one day and found I couldn’t hit. Would I quit? It all depends on the circumstances. If someone wants to pay me an extra $1 million a year, even though I can’t play good any more, what am I going to tell them? Take your million and stick it? Absolutely. Stick it right in my back pocket….”

He wore Cincinnati World Series rings on both his hands. His eyes were never still. As he talked, the stream of autograph seekers continued unchecked. In 14 minutes he shook hands with 11 strangers, signed 11 slips of paper. With each new supplicant, he focused for just one beat. In that instant he caught them, swallowed them whole. Then he signed, and they ceased to exist.

It was the same with baseball. Right before each pitch, he could joke with the catcher, the home-plate umpire. He only concentrated when the pitcher went into his windup. He switched off and on at will, and this had probably helped his longevity. There was no wasted energy. And now he reaped the benefits. When next season came round, he would turn 40. But he noticed few signs of decline. His body still obeyed him. So did his will. For the moment, he had frozen time.

After this, the forum itself proved something of a shambles. The audience was split between earnest fathers and sons, indifferent mothers and daughters. Babies howled. Many questions were inaudible. Even Rose seemed discouraged. But he soldiered on. “Do you still play baseball for fun?” a fat man asked.

“Sure I do,” Rose replied. “And if someone paid you $6,000 a game, you’d have fun as well.”

Lou Carnesecca had a cold. He caught them frequently. In his office at St. John’s, in the hinterlands of Queens, the walls were covered with pictures, plaques and certificates. Above his desk there hung a large impressionistic painting, a vision of basketball God, floating weightless and free above the court, omnipotent. But the coach was short, round, vaguely furtive. He peered over half-moon glasses perched on the tip of his nose. He looked like a defrocked priest.

Pumped full of antibiotics, he wore a bright red track suit to match his eyes, and his voice, always hoarse, was reduced to a whispered croak, like a laryngitic bullfrog. “Would I have liked to be an athlete myself? Who’s kidding who?” he rasped. “A player today has a lifetime career of maybe 10, maybe 15 years. But a coach stays around. If he doesn’t get fired, it’s like a license to eternal adolescence.”

New York was basketball Mecca, and Carnesecca spoke its language, understood its angles. For years he was a gym rat, scuffling at the edges.

In style, Carnesecca was archetypal New York; the born street survivor. He was raised white Catholic in East Harlem. He played baseball on the sandlots, basketball in the playgrounds. His father wanted him to be a doctor and play the accordion. So he took up the clarinet and lived for basketball. He was too slow, too small to play well himself. But that only strengthened his addiction. In the players who outclassed him, he saw athletic perfection, the blending of power, grace, control. If he couldn’t share such gifts, at least he could help refine them. By the time he was 21, he had made coaching his vocation.

New York was basketball Mecca, and Carnesecca spoke its language, understood its angles. For years he was a gym rat, scuffling at the edges. Finally, he wound up at St. John’s, one of the sport’s traditional shrines. For eight years he was assistant to Joe Lapchick. When Lapchick retired, in 1965, he was the automatic successor.

By now his image was firmly fixed. The tubby little figure, dwarfed by his own players; the rusted B-feature voice; the street-smart one liners and frantic courtside gesticulations; the surface flipness; and the gruff warmth beneath—combined into an identikit, a New York cartoon, whom the press named Little Looie.

Showbiz apart, he also knew his trade. Under his command the Redmen averaged 21 wins each year. In his first 12 seasons, while compiling an overall record of 256-90, they were invited to eight NCAA tournaments and four NITs. Apart from a three-year sabbatical in the pros, coaching the Nets in the ABA, Carnesecca became a fixture. The St. John’s inheritance, created by Buck Freeman, nurtured by Frank McGuire and Joe Lapchick, was safe.

His major problem was recruiting. The brightest local talents tended to migrate. Dozens of schools around the country promised them nirvana. The best St. John’s could do was an undersized gym and locker rooms like cells, plus a decent education. Most often it wasn’t enough.

Carnesecca accepted that. When prospects turned him down, he wished them well, and he waited. Quite often they returned. In recent years three starters, Reggie Carter, Bernard Rencher and Curtis Redding, had all traveled west, to Hawaii, Notre Dame and Kansas State, discovered that nirvanas didn’t always live up to advance publicity and wound up back in Queens. “My door doesn’t shut. They know where they can find me,” Carnesecca said.

Yet his failings, as he himself admitted, were glaring. He was hopelessly disorganized. Not the Germanic type, more a man of Latin chaos, he said. And he could not control his emotions. In practice, he’d often drive his players to the snapping point. He had no sense of proportion. After more than 30 years, he still didn’t understand that basketball was a game. But nobody seemed to bear a grudge. Each of his recruits became an adopted son. He worried about their grades, their love affairs, their families. Even when they’d graduated, he was always there for them, in need. “Part Mother Hen and partly Father Confessor,” he said. If he sinned, it was only because he cared so much.

His passion for the game remained all-consuming. It ruled his family life, his friendships, everything. He wished he could relax. His daughter loved art. When they visited Spain on tour, she took him to see the Old Masters. They were good. Some were even beautiful. But none as beautiful as a fast break. “I guess I’m a terminal case. A hopeless junkie,” he confessed. “When they show me a Picasso, all I see is lots of X’s and O’s.”

At 56, looking back, nothing in his career seemed wasted. His stint in the pros hadn’t worked out. But it had taught him his own limitations. He was basically a teacher, a leader rather than just a conductor. But professionals would not submit to that. They were businessmen, first and last. Their basic situation was labor versus management, and there were no loyalties—not on either side. The players pushed for top dollar. Management tried to beat them down. And the coach was trapped in between.

In bygone years the comedian Harry Ritz did a routine called the Man of the Seven Afflictions. Little Looie, apparently, had been stricken with the entire set at once.

In college, the cynicism was less open, he said. Even so, with the involvement of network TV, the amateur spirit had died. In reality, money had taken over. Yet the players never saw a cent. That was blatant hypocrisy. They drew the crowds, took the risks. Therefore, they should be rewarded. If justice had any logic, there should be an independent college league, say 20 or 30 of the top schools, and the players should be salaried.

Inevitably, heresies such as these had brought him enemies. Some saw him as a mad bomber, plotting anarchy and destruction. But that was their problem.

Right now his problem was to get his team playing better. This season was not proving easy. Although they were 5-1, the Redmen lacked height and muscle up front, experience in the backcourt. If they came up against a powerhouse, he had a suspicion that they might get massacred.

Luckily, the next game was against Fairleigh Dickinson, 2-5. A few minutes before halftime, the Redmen were up 34-12, but it wasn’t truly that close. To judge by Carnesecca, however, it might have been a struggle unto death.

In bygone years the comedian Harry Ritz did a routine called the Man of the Seven Afflictions. Little Looie, apparently, had been stricken with the entire set at once. With every shot, at every rebound, he would flinch, stagger backward, then double over in cramps, race down the sideline in a hernial crouch, shouting incomprehensible instructions, waving his arms like a deranged windmill, spewing forth obscenities, his head clutched in his hands, his face an apoplectic purple.

The crowd followed his every gyration. At climactic paroxysms, even the referees sneaked a peek. When at last Carnesecca desisted and sank into a chair, his fans applauded as one.

At their home in Jamaica Estates, meanwhile, his wife, Mary, paced the floor, saying a few prayers. If the Redmen contrived to lose, Looie would come home incoherent, jabbering. There would be a sleepless night, and

his cold might turn to bronchitis. If they won, on the other hand, she could relax. No cause to worry until Friday, and the tournament game with Penn. “When that woman dies, she’s going straight off to heaven. Just open the gates and wave her through,” her husband had confided. “All the years we’ve been married, she’s been a martyr to my cause. I’m never there. Even when I am, I’m really not. She lives with a missing person. On permanent Injured Reserve.”

For the moment, however, all was well. By the new year, the Redmen were 7-2. All trace of the seven afflictions had vanished. “Life is good,” Little Looie said. “But basketball is better.”

[Image Credit: Sam Woolley/GMG]