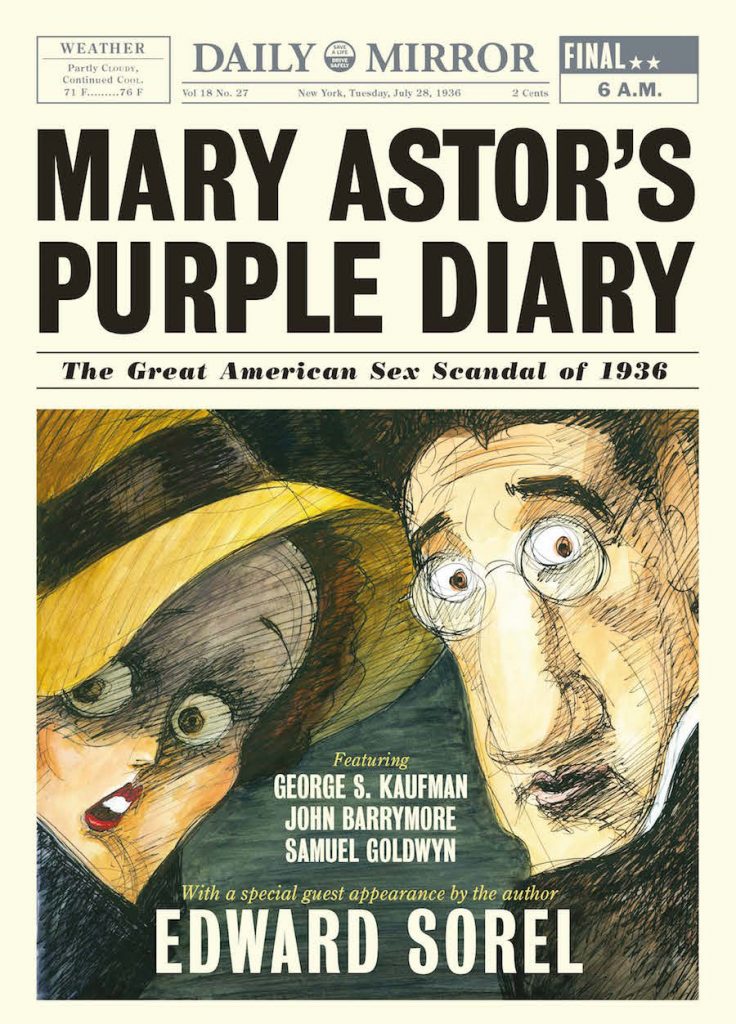

Edward Sorel is one of the finest—and funniest—caricaturists this country has ever produced. Although he works in a variety of styles, you’ll likely recognize his work right away—you’ve seen it in Esquire, Harper’s, The New Yorker, and Vanity Fair, to name but a few publications that have featured his work over the past 50 years. Sorel’s got a new book out, and it’s a real charmer—Mary Astor’s Purple Diary: The Great American Sex Scandal of 1936. Blending reporting and memoir (and even some fiction) with his characteristically expressive—and funny—illustrations, Sorel’s story is moving, and as engaging a read as you’re likely to find this fall. At 87, he is still plagued by insecurity and yet here he stands, very much at the top of his game. We spoke last week in his New York apartment about the art of comic storytelling, his work for Esquire, and his irresistible new book.—Alex Belth

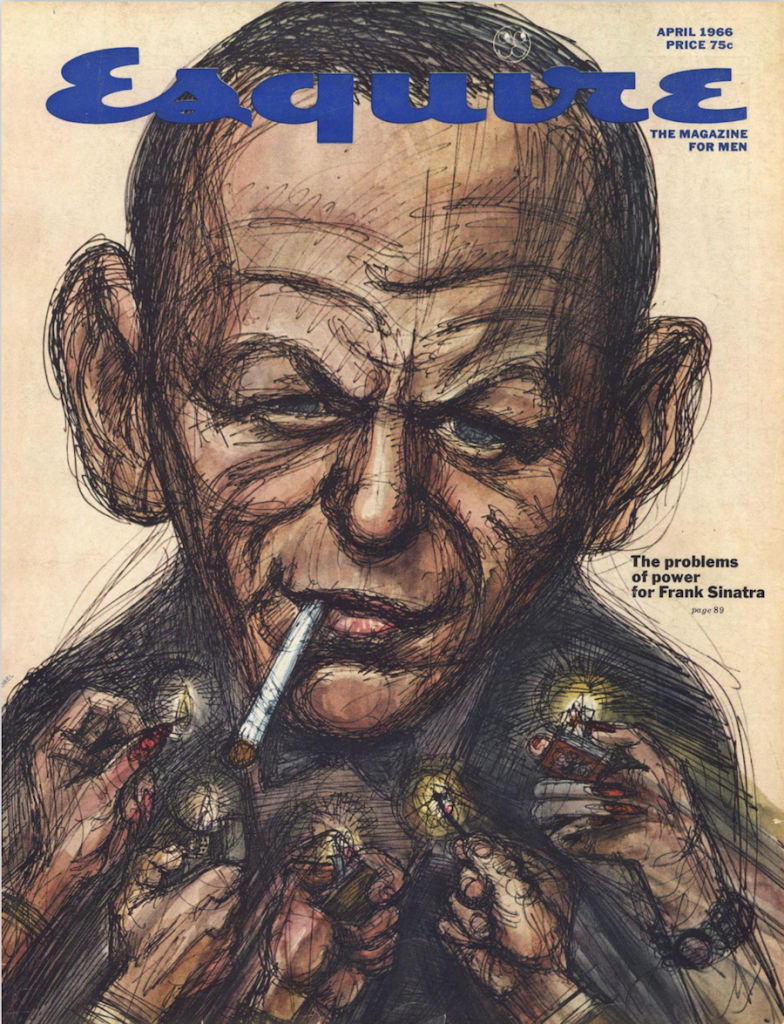

Esquire Classic: Let’s begin with the first cover you did for Esquire, the drawing of Frank Sinatra for the April 1966 issue for Gay Talese’s celebrated profile, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold.”

Edward Sorel: What I remember was that George Lois, who was creating the covers, couldn’t get Sinatra to pose. George had this brilliant idea of a closeup of Sinatra, who had a lot of flunkies, showing several hands trying to light his cigarette.

When George gave me this job, it was a particularly low point in my life. I’d left my first wife, I was completely broke. This was a big job. I always get scared doing a job. To this day, I start every job thinking, I really can’t do this. And what I do when I’m insecure is I tighten up. So I did a rendered drawing of Frank Sinatra having his cigarette lit. And George looked at it and rolled his eyes and said, “This isn’t any good. I’ll give you until tomorrow to do it over.” So I did another drawing overnight, and working on adrenaline, it came out fine. If you work through the night you can do anything.

C: Did you know that you’d nailed it?

ES: I never know if it’s good until I see it in the magazine. But that picture changed my entire career. It’s now in the Library of Congress. They just bought it about three years ago. One of the best drawings I did was of Edward G. Robinson for The New Yorker and it was an overnight job. So you never know. You can have all the time in the world with a drawing and screw it up or do one overnight that turns out great.

EC: Do you ever find yourself getting too self-conscious when you are working on a drawing of a recognizable face?

ES: Sure, and every now and then I’ll overwork a drawing in my desire to get it exactly right and I lose the caricature and it ends up looking like a line drawing of a photograph. You can go through 20, 30 sheets of paper before you get it right if you are working directly on the paper and not tracing. If the picture is complicated then I trace to a certain extent to have some idea of where I’m going with it. Blocking out where everything is going. Otherwise it ends up in disaster

The big problem for comic art is you don’t want to overwork it. If a drawing is overworked it isn’t funny. It’s the spontaneity that keeps a work fresh and funny. It’s the Fred Astaire syndrome—make it look easy. If they can see how hard you work, if they can see the beads of sweat, it’s no good. I always try to make it look easy.

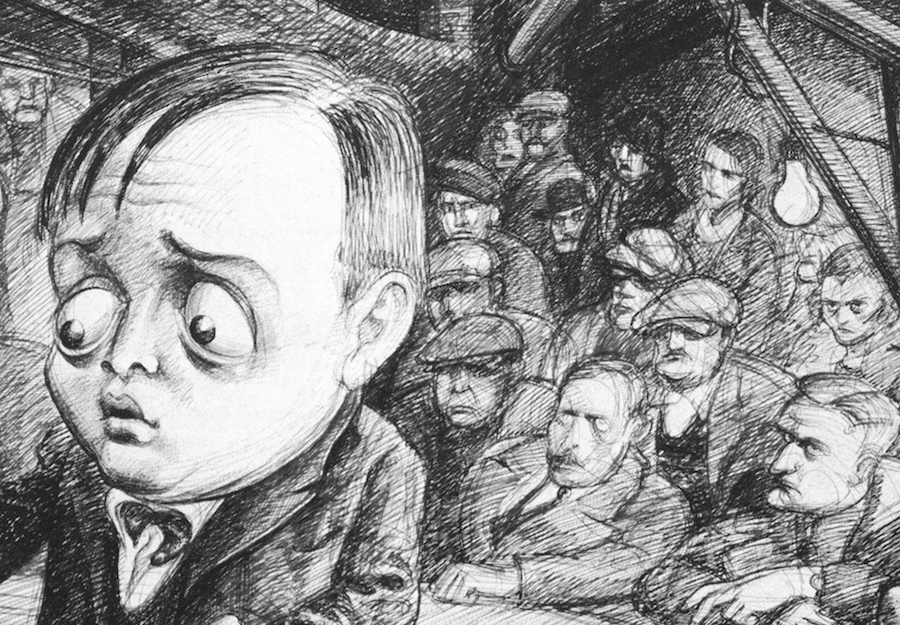

I just didn’t have enough time on some of the Movie Classics pieces I did for Esquire in the early ‘80s. Some of the illustrations were just lousy. And some of them were brilliant. It all depended on how much time I could give it. The one of Peter Lorre in M is one of the best drawings I ever did. And I did it direct with no tracing and it has enormous power. I love that picture.

EC: Do you always work from photographs or existing sources or do you use live models?

ES: My one failing as an artist is that I depend on reference material to perhaps a greater extent than I should. Delacroix said that if you can draw a man falling out of a window and have the drawing finished before he hits the ground then you’re a real artist. I wasn’t that kind of artist. I love being convincing. I love when a gesture is convincing and I love doing research for a picture. Citadel books used to do books on movie stars. I must have had 30 of them. Movies are a great place to get gesture and composition. If you’re telling a story you need a background. Just like a novelist needs background information to make a story interesting, I think an artist needs it for a picture too.

The idea is to use the reference and then caricature everything, including the background. One time a magazine sent me out to cover a car auction and I caricatured the cars. I didn’t do it on the spot. I took pictures of the cars and then took them home and then did the drawings. You can caricature anything, including a gesture. You have to know what to exaggerate to make it funny.

EC: Did you do a lot of drawing when you were at Cooper Union?

ES: I saw maybe two naked models in my three years at Cooper Union. I was there from ‘49 to ‘51. It was a three-year, diploma-granting institution at that time and they weren’t interested in drawing, they were only interested in design. They were trying to make everybody into Stuart Davis. None of those art deco guys date very well but Davis was better than most. So I did Stuart Davis for a few years and I did it very well but I hated it. Design still doesn’t interest me. I started Push Pin studios with Seymour Chwast and Milton Glaser who were the most brilliant designers of that period. But design did not interest me. I could do it if I had to. But I liked just drawing.

I wanted to be John Sloan or George Bellows or Maurice Prendergast. I wanted to be part of the Ashcan School. But by the time I was in Cooper Union the Ashcan School was laughed at, they were objects of ridicule. You’d show someone Reginald Marsh and they’d snicker. But that’s who I wanted to be. When I went to school the New York School was flourishing. That meant Franz Kline and [Robert] Motherwell, and all those no-talent assholes. So there was nothing for me in fine art anymore. Besides I liked drawing stories. And I love comic art.

EC: Were you amused by some of the pop artists in the ‘60s? Was Lichtenstein funny to you?

ES: Well it was funny…for a while. If he had done two or three of them it would have been amusing. But to spend a whole life doing this small joke? Insane! You’d also have to be crazy to buy one of those paintings and wake up every fucking morning having to look at it.

The artist that I always wanted to be was Feliks Topolski who was a Polish artist who spent World War II in England. He was a great caricaturist. I couldn’t do what he did. David Levine was the patron saint in our field. He was so nice and so helpful to everybody. In the ‘60s, everybody was imitating David Levine. I illustrated the very first issue of The New York Review of Books. For the second issue they got David and he stayed with them forever after that. When people saw what he was doing in The New York Review of Books he was given bigger things to do like that famous gatefold in Esquire of Truman Capote’s Ball. It’s fantastic. It’s just unbelievable. And I think he must have done it in a matter of weeks. It was an amazing piece of work. He drew so well. I was always so envious. He had gone to Temple University where they put great stress on live drawing. He didn’t have to find reference for gesture. He’d done so much live drawing, he could make it up in his head.

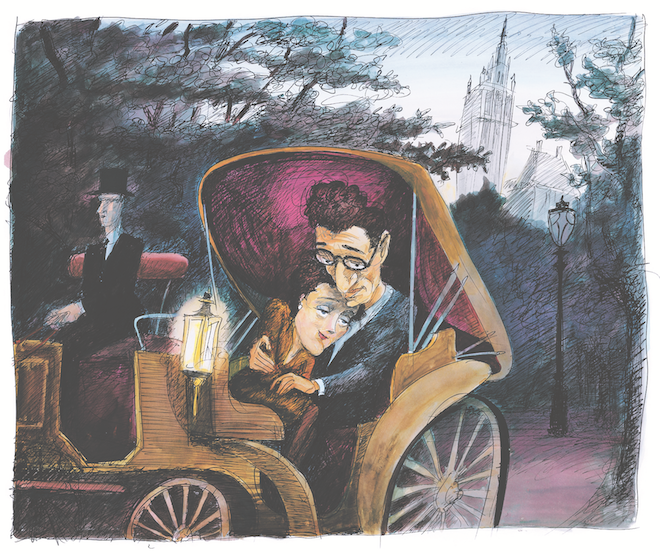

EC: So, let’s talk about your new book, which is a delight. Were you a Mary Astor groupie growing up?

ES: I remember her as being so beautiful in The Prisoner of Zenda. I was ten years old and she was just a knockout. But she wasn’t part of my movie memory because the truth of the matter is she wasn’t in any good movies except Dodsworth and The Maltese Falcon and, according to you*, The Palm Beach Story, which had its moments but was too silly. She wasn’t in many good movies, really. She had a terrible father who was only interested in money. He kept her subservient and submissive and she couldn’t shake it when she became an adult. She never asserted herself. She was always looking for men who would take care of her and of course what they did was take charge of her as opposed to taking care of her.

Mary Astor didn’t want to become a star. Two studios offered her a contract for starring roles—Paramount and RKO—but she turned them down and went to Warner Brothers who put her in schlock movies. She did six movies for Warner Brothers in one year. But she did remarkably well in these terrible movies.

EC: Sort of like Ava Gardner but a better actress?

ES: Ava Gardner made a lot of bad movies but you don’t fall in love with her. You can fall in love with Mary Astor—as in Dodsworth. Oh my God, she was the most desirable woman in the world in that movie. My late wife was an exceptionally beautiful woman. But she wasn’t glamorous in the way Mary Astor was. I wouldn’t know what to do with a glamorous woman.

EC: Except feel inadequate all day?

ES: My feelings of inadequacy are not limited to glamorous women. And Mary Astor may have had her own feelings of inadequacy which played a part in her refusing contracts for starring roles. She said she wanted supporting roles because she would have a longer career that way. She was right. She started in movies in 1920 and was still doing them in the early ‘60s [Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte, the camp classic starring Bette Davis, was her final appearance]. So she had a long career, but Mary Astor had the ability to have been a great star if she had felt an obligation to her talent. There are actors who somehow can’t respect acting. Sometimes, I think, it’s because it comes too easy to them. Think of Robert Mitchum.

Astor may not have thought she was good enough. We all wish we were better. I wish I were a better artist, wish I were a kinder person, wish I were all kinds of things. But we’re stuck with ourselves. I have good friends. And that in itself convinces me that I deserve to live. Looking back I realize I had the perfect family background to become the political cartoonist that I became. My father was stupid, insensitive, and cruel, thereby making me distrustful of all authority. On the other hand, I had a warm, supportive and encouraging mother, which made me want to fix the world.

I was always nervous, always scared. That’s stayed with me my whole life. I think it’s all our genes. I have four children, two daughters from the same mother and father, same environment, and they’re quite different. So how do you explain it except they are genetically different somehow? We’re all stuck with ourselves. I wish I were calm. I wish I were William Powell or Jean Gabin. Never get scared, always calm, but that’s not me. I panic easily.

EC: How did the book come about?

ES: In 1965 my new wife and I were lucky enough to get a rent-controlled apartment for $97.14, but it was a wreck. When I removed the cracked, decaying linoleum in the kitchen, under several layers I discovered issues of the Daily News and Daily Mirror from July of 1936. Both carried gigantic headlines about Mary Astor’s diary, that her ex-husband, who had stolen it, was threatening to use at their custody trial to prove that Mary was an unfit mother. He claimed that she kept a record of all her extramarital affairs in it.

After that I read everything I could about the trial, and about her life, and about George S. Kaufman, with whom she had carried out a bi-coastal affair for three years. Clearly my interest was largely prurient in nature. Like every young man growing up in the puritanical Eisenhower 1950s, I had a hell of a time getting laid. I suppose that’s why I was always intrigued by, and terribly envious of men like George S. Kaufman who had no trouble at all in bedding a vast variety of desirable women.

The more I read about the trial the more fascinating it became. I found out how the major Hollywood studios, particularly MGM, controlled the Los Angeles police department, and the Governor of California, Frank Merriam. In 1934 with the Country in the depths of the Great Depression, Upton Sinclair, an avowed Socialist, was way ahead as the Democratic Party’s candidate for Governor of California when Louis B. Mayer had MGM produce a fake newsreel showing all the terrible things that would happen if Sinclair got elected. After that newsreel played in theaters Sinclair lost, and Merriam got elected. Now anything that Mayer wanted from the Governor he had no trouble getting.

What Mayer wanted was to keep Astor’s diary from being read in court. The studios were terrified that Hearst would start another campaign against “sin in Hollywood.” I’m convinced that the judge in the case, Goodwin Knight, was told by the Governor to end the trial without letting the contents of the diary out. That’s what he did. Knight later became Governor himself, and for a while in 1940 even became a serious candidate for the Republican nomination for President before Wendell Wilkie got the nod.

You see how writing this book took me into so many fascinating places. If I had realized how rich the material was surrounding the trial, I would not have waited half a century to get around to writing and drawing it.

EC: Was it fun to recast the story with you in it?

EC: Was it fun to recast the story with you in it?

ES: Yes, yes. As soon as I was in the story I loved it because I could make editorial judgments about the action and that was fun. I was even able to get off a gag line here and there. At one point while writing the book I felt obliged to defend my obsession with Mary Astor despite the fact that she was an alcoholic who believed that joining the Catholic Church would solve all her problems. I admitted it was odd for an atheist to choose such a woman for worship, but explained: “Isn’t every couple an odd couple? Why would Chopin, who had TB, fall in love with a woman who smoked cigars? Why would Donald Trump, who prides himself in good taste, fall in love with Donald Trump? Obsessions by their very nature defy reason.” Suddenly, I was writing the story for my friends and not just a faceless public.

EC: Do you do that often? Write stuff with your pals in mind?

ES: I guess I do, though I never thought of it that way until now. I’ll think—My friends will like this one. And that’s what you’re really working for—you’re really working for your friends.

EC: So, are you pleased with how the book came out?

ES: Oh, delighted. Absolutely. I surprised myself. I just kept writing and writing and it seemed to get better and funnier. I got more secure and the pictures got better and better. I suppose I should have written a little more, it’s a little thin, it’s only 165 pages. There’s plenty more I could have said. I do good drawings, I do lousy drawings. I have a middling batting average, the way I see it, as opposed to David [Levine] who batted 1.000 as far as I was concerned. He never missed. I miss on occasion.

EC: Did you miss less as you got older?

ES: Yes. Well, as I got older I didn’t have to make as much money, so I can devote the proper amount of time to a drawing. No tight deadlines now. If it doesn’t come out I just do it over.

EC: Do you ever come to a dead-end with a drawing and reconceptualize the entire thing from scratch?

ES: Yeah. When a drawing doesn’t come out right it’s because I haven’t figured out where the joke is. Not that every drawing has a joke, but every drawing has a point. At least it should have. And you figure out where the point is. What’s the point of this drawing? You know when it’s wrong. But if you’re lucky there’s time to fix it. If you’re not lucky, they publish it and everybody tells you how much they love it and I know they’re wrong. Sometimes I’m wrong. The drawing’s not half bad.

* Before we started our formal interview, I made a case for The Palm Beach Story, which also happens to be the Coen brothers’s favorite Preston Sturges movie.

Illustrations reprinted from Mary Astor’s Purple Diary by Edward Sorel. Copyright (C) 2016 by Edward Sorel. With permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved.