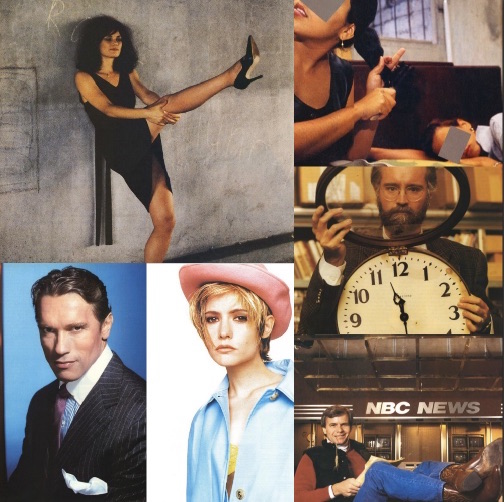

Lynn Darling was a bright and lively presence at Esquire from the mid-’80s through the late-‘90s. She wrote smart, observant celebrity profiles of Arnold Schwarzenegger, Tom Brokaw, Jennifer Jason Leigh, and Linda Fiorentino. But her speciality was sex and she weighed in on relationships between men and women in features like “Sex White Male, Seeks Clue,” “Havana At Midnight,” and “Sleeping with the Enemy.” Her best story, however, might be “True Blue,” an empathic but clear-eyed portrait of steel miners in Pennsylvania, that rings especially true now in Trump’s America.

In addition to her work for Esky, Darling was also a longtime contributor to Style at The Washington Post as well as Harper’s Bazaar. She is the author of the terrific memoir, Out of the Woods. We caught up with her recently at home in Manhattan where she was as sharp and witty in conversation as she is in print.

Alex Belth : When did you first get into journalism?

Lynn Darling: I started writing at The Harvard Crimson. I went to Harvard from ‘68-‘72, and what I loved about becoming a reporter was that it was “Them” and “Us.” “Them” was the establishment, and we were trying to stick pins in them. Everything was breaking out with the New Journalism, so it was dazzling, it was a revolution as far as we were concerned. Esquire was the magazine to read. You waited for the next Truman Capote installment, for war correspondence from Michael Herr and John Sack. In the early to mid-‘70s, you took a little opium, went up to the roof and read Esquire. Or you didn’t do the opium but you still read Esquire.

AB: What was your first job out of school?

LD: There were a group of people from Harvard who started up an underground paper in Richmond, Virginia called The Richmond Mercury, including Frank Rich. That’s where I began. Ben Bradlee saw some of my writing and I got a try out and then a job at The Washington Post. I wrote obits, I ran after fire alarms, I covered insanely boring county board meetings. I worked the police beat. Try calling up someone whose just lost their kid in a murder situation or whose husband has just been taken hostage at three in the morning and saying, “Hi, how do you feel? I want to quote you and put it in the newspaper.” You have to do it. You don’t really have a choice. For a young reporter it was boot camp and the most invaluable experience in the world. It was learning the old-fashioned way. My mom was so depressed when I became a reporter because it was such a raffish profession. It wasn’t glamorous like Woodward and Bernstein.

AB: But was it glamorous in how unglamorous it was?

LD: To us it was. We thought we were so cool. I was identified as a feature writer, which is how Shelby Coffey, editor of Style, which was in its heyday, noticed me. We were called “the Sandbox” at the paper. We were a bunch of children who rambled on at length about nothing. It was great!

The first piece Shelby wanted me to do was on a bandleader named Peter Duchin, who was the society bandleader at the time. I asked Shelby, “What kind of story do you want?” And he said, “I’m looking for an elegiac tone-poem.” My first reaction was, “Oh?” And my second reaction was, “I’ve just gone to heaven.” And it really was heaven. Shelby was the kind of editor who would call you up and read you a haiku when you were struggling with a piece to get you in a certain mood. And recommend certain books to get you in the right flow for a story. Or propose a lede like, “Why don’t you try something along the lines of ‘16 Different Ways of Looking at a Blackbird.’ That might work.”

I’d come in depressed if a story didn’t work. It was like the perp walk. If your piece tanked, the silence was really bad. It was all egos and talent in that tiny little pool. Envy would have been okay, but silence was the worst. But I’d come in crying and Shelby would say, “Hey, a good batting average is one out of three.” That’s the same as writing a feature story. One is going to suck, one is going to be mediocre, one is going to dazzle. If you can do that many dazzlers you’re going to be okay, just keep writing.

AB: Sounds like a good way to keep yourself centered.

LD: Ben Bradlee would say, “Don’t get too puffed up kid, whatever you write today is lining the bird cages of the rich and influential tomorrow.”

AB: That’s great. Okay, so when did you start writing for magazines?

LD: I wrote for Style for five or six years and had a scandalous affair with the man who would become my husband. When he left The Post to go to The Wall Street Journal I left as well and came to New York. I didn’t have a problem meeting magazine editors and getting my foot in the door simply because I had worked at the Style section. So I started freelancing and that led to contracts with Esquireand Harper’s Bazaar.

AB: And you wrote for New Times too, right?

LD: I did a piece for them back when the right-to-life movement was getting started. As feminists and progressives, we had totally demonized these people and hated them and thought they were awful. They had no idea what had just hit them, a complete hurricane had gone through American culture. Their kids went away and turned into hippies, people didn’t have to be married to have sex anymore, you name it. The generational divide between my mother and me is that her generation never put on a pair of blue jeans. And never would. They would have killed themselves first. Everything had changed so that I suddenly had sympathy for these people—not their politics—but sympathy for the shock they were going through. Nothing made sense to them. It’s kind of like being Democrat since Trump won the election. Their whole world had been turned upside down and marching was the only way they knew how to keep the old way going.

AB: Did you find the same thing to hold true for “True Blue,” your 1985 feature about steel workers in Pennsylvania?

LD: The hardest thing about that story was cracking that community because they hated outsiders. They were angry and were a very tight-knit group. I banged on 7,000 doors before anyone let me in and when the one guy finally let me in I asked why. And he said, “Your smile.” It’s that simple. People either connect to you or they don’t. But you use whatever charm you’ve got to get in there.

I liked lost worlds. “True Blue” was a lost world that was very personal to me because my grandfather was a steel worker. My mother grew up in those towns, just outside of Pittsburgh. The soot was so black you couldn’t see, but a man without an education could earn enough money to send his kid to college. There was a dignity to those lives. You could make fun of them because they were practically illiterate and they drank too much and had incredible prejudices. But within all of that were these incredibly close families that had paid dearly for their houses and cars. They came from a place of want.

AB: How do you reconcile being judgmental and being open-minded?

LD: That’s why writing saves me. Because you can’t write without trying to get into somebody else’s skin. If you don’t understand the humanity of a person you can’t write about them.

AB: You talk about being judgmental, having a take, having a strong voice. Were you ever worried a subject would take it the wrong way?

LD: I’m much more worried about being misunderstood by an ordinary person and I was by the guy I wrote about in “True Blue.” He felt bad about the piece and I meant to hold him up as this wonderful guy. Celebrities? Hell no. Who cared? They were only talking to me because they had something to promote. Some of them I liked, some of them I didn’t, but I didn’t think about that in terms of what stories I wrote.

AB: So you weren’t afraid of pissing people off?

LD: Well I don’t think my generation of reporters could afford to be afraid. That’s what I mean about the “Us’ and “Them.” Some of my best friends are still the people I worked with at The Post when I was 23 and we talk and feel that occasionally we were clever at the expense of being kind. Not kind—just. What I was told at The Post is you can’t be totally accurate, there is no truth. But you can be fair.

AB: Did you enjoy writing about celebrities?

LD: I didn’t mind doing profiles. Celebrity profiles can be a window into whatever you want to talk about, they are a trope. But it has closed off now to the point where it is all in the hands of flack, and people will ask you to submit pieces before they will allow you to interview them, which is just a totally different world. It’s very hard to get a good profile out of somebody who is giving you twenty minutes in a hotel room.

The reason Tom Brokaw was so wonderful was because he is basically a reserved man and had no idea the kind of piece I was going to write but he took me everywhere. He took me to the town in South Dakota where he was from, the bar where he used to hang out, we met his childhood friends. I hung out in the newsroom, I watched him prep for an interview, it was just total access. Willi Smith said to me, “What are you, my ghost?” But it was just taken for granted that in order to write a good story you had to be on them like white on rice. Because half of your story wasn’t what they said, it’s about how they reacted to other people, situations, change. And you could ask them off-the-wall questions because you weren’t in a formal interview all the time.

AB: That kind access just isn’t there today.

LD: It was the access and also the license. You just didn’t feel like there was anything you couldn’t say. People would tell you when they wanted you as a writer—and it wasn’t just me—“We love your voice.” That meant whatever you wanted it to mean. We like the way you talk about values, or the way you’re provocative about this, or the way you turn a line. They didn’t want run of the mill, and they didn’t want something that was too safe. They wanted you to have a point of view. That’s what voice was. And to write in a certain style—whatever that was—and to be playful.

Nobody called it a voice until I came to New York. It doesn’t have to be provocative or outrageous, a voice can be extraordinarily subtle. Have you said what you wanted to say? Have you said what was important to say? Those are the two questions that you need to ask. I can look back on old pieces of mine now and see where I didn’t dig deep enough.

David Hirshey was my editor at Esquire and he kept you honest, made you dig deeper, really think about what you’re trying to say and not just skate. Because if you’re a stylist—and everybody who wrote for Esquire was—you can always skate and not have anything underneath it but a thin layer of ice. The integrity of the piece was more important to Hirshey than the ego of the writer. If he saw a weak spot in the piece then you had to fix the weak spot. Pour in the concrete, smooth it over. Or, if it was a bearing wall and it didn’t bear, down with the bearing wall. You had to start all over again.

Everybody hates to murder their darlings but as you get older you get better at it.

[Photo Credit: Zoe Lescaze]