For two summers while I was researching the biography When Pride Still Mattered, I lived in New York. Day after day I would venture out to Sheepshead Bay, where Vince Lombardi was born and reared; or up to Fordham University in the Bronx, where he went to school and had his first brush with legend as one of the Seven Blocks of Granite; or across the river to Englewood, New Jersey, where he taught and coached at little St. Cecilia’s; or farther up the Hudson to West Point, where he learned his football philosophy as an Army assistant under Red Blaik.

But the trip that had the most lasting impact on me during that period of research was a longer ride into New England to a hilltop home in Dorset, Vermont. It was there that I met and spent a memorable day with the writer W.C. Heinz.

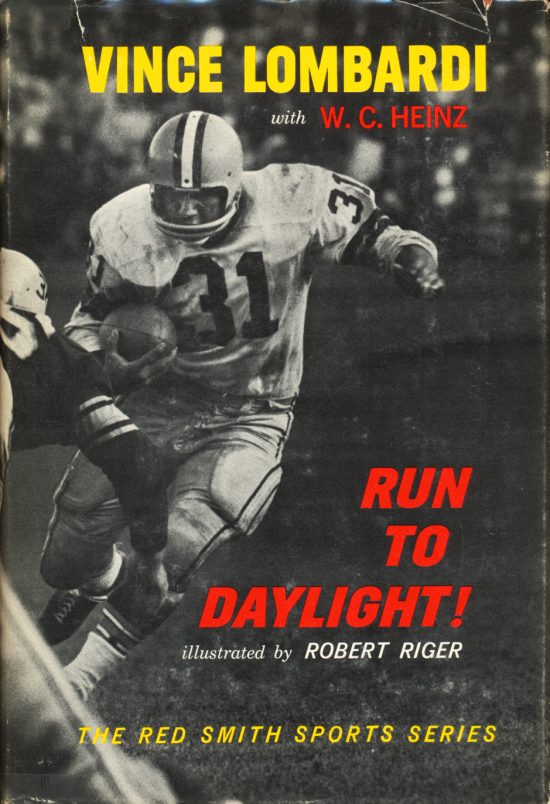

I came to Run to Daylight! early, but to Bill Heinz late. The book that Heinz wrote under the byline “Vince Lombardi” was a staple of my mid-1960s Wisconsin childhood. I read it again and again, until the cover was gone and the pages were watermarked and smudged by mustard and dirt. I knew the book the way Lombardi’s Packers knew their Packer sweep after practicing it over and over. And every time I read it, I was thrilled anew by the game-clinching play when Milt Plum of the Detroit Lions throws a pass and the receiver slips and Green Bay’s dashing young cornerback swoops in and, as Lombardi in the book describes the scene, “I hear the thop-sound it makes as it hits Herb Adderly’s hands, and he’s got it. He’s got it, and he’s racing right by me now, down our sideline.”

It was three and a half decades after that October 1962 game that I found Heinz standing in the driveway of his Vermont retreat. He had been forty-six when he wrote the book, and was eighty-one by the time I met him, but he still looked much like the writer I had seen hovering near Lombardi in old photographs. He was wiry, crisp, and clean and lean, his mind as sharp as ever. Through his thick black-rimmed glasses, he saw the world with uncommon clarity.

Over the course of a long and enjoyable morning and afternoon, he showed me the tools of his trade.

I arrived in Vermont with simple questions: What was it like to write a book with Vince Lombardi? Step by step, how did you do it? I left with the answers, but also with a deep appreciation of Wilfred Charles Heinz and his writing craft.

Over the course of a long and enjoyable morning and afternoon, he showed me the tools of his trade. He still had the old Remington manual typewriter on which he punched out Run to Daylight! and many other books (along with untold hundreds of newspaper columns and magazine stories). Of more material value to me, he dug into his closet and brought out a set of old Penrite memo books—ten cents apiece, spirals on top, neatly marked 1, 2, 3, and 4. Inside the notebooks, in neat handwriting (shockingly neat for a reporter, I thought), were all the notes Heinz had taken from his many interviews with Lombardi during his time in Green Bay. As a writing colleague, Heinz knew the notebooks would be as important to me as anything he said. And he was such a mensch that I didn’t even have to ask—he handed them over to me for my use and safekeeping.

The stories he did tell me that day were unforgettable. He talked about the legendary writers he had learned from over the course of his long career. Most of them were sportswriters, but Heinz made no distinction. He agreed with me that writers were writers, and much of the best writing happened to involve sports. He had covered sports most of his career, though during World War II he served as a war correspondent with distinction for the New York Sun. After that he wrote a sports column, then turned to books (including the book on which the movie and TV show M*A*S*H were based) and freelance magazine articles when the Sun folded. He was a favorite of Grantland Rice and Damon Runyon (as Runyon was dying, he scribbled on a bar napkin that Heinz was his choice to replace him as columnist for Heart’s Cosmopolitan), and a close friend of Red Smith, then of the New York Herald Tribune, later of the New York Times, who was ten years his senior. He admired Smith’s writing, but considered him “more of a dancer and mover, with a style you couldn’t imitate.” The writers he most closely followed in style were Ernest Hemingway for novels and Frank Graham for everything else.

It was from Graham, Heinz said, that he learned how to construct an English sentence, and how to be a fly on the wall, to catch athletes at their most authentic moments and then use their dialogue verbatim to re-create a scene—all without a tape recorder and without taking notes until later. “Frank never took notes, so… I learned how to do that too, how to look and listen,” Heinz told me. “The first time I tried it, Frank and I were both interviewing Rocky Graziano at Stillman’s gym. He wasn’t taking notes, so I wasn’t either. When we came out I said, ‘You jerk! I don’t think I’ll remember.’ He said, ‘You will. When you get home tonight and Betty [Heinz’s wife] asks you where you were and what you did, you’ll tell her who said what and where you were and what you did.’” Graham was right, and the powers of memory that Heinz developed then stayed with him thereafter, so four decades later he could remember the smell in the air and the color of a tie. Still, as a backup, he continued to take copious notes in his unhurried longhand.

“Did you ever hear Lombardi tell a story up there? He’s got a great laugh, but he doesn’t contribute. That’s gonna be a problem.”

His pal Red Smith sent him out to Green Bay. Smith had been signed by Prentice Hall to serve as general editor of a series of as-told-to sports memoirs, and it was decided that the series should start with the most famous coach of the moment, Vince Lombardi, whose Packers had won the NFL title in 1961. Smith’s first choice for the assignment was Tim Cohane of Look magazine, who was Lombardi’s old Fordham pal, but Cohane declined, saying he was too busy, so Smith turned to his friend. Heinz said he was still finishing a novel, The Surgeon, but would be done in time to get out to Green Bay for preseason training camp. Heinz and Smith both knew Lombardi from his days as an assistant coach for the New York Giants, and what Heinz remembered especially was a trait that might make the book difficult. “Here’s the problem,” Heinz told Smith. “Did you ever hear Lombardi tell a story up there? He’s got a great laugh, but he doesn’t contribute. That’s gonna be a problem.”

He was right. Lombardi was a problem. At first, when Heinz reached Green Bay, the coach seemed gracious enough, picking the writer up at the airport, inviting him to stay at his home on Sunset Circle, even staying still long enough for an interview. But it was not long into the first interview when Heinz grew frustrated, chiding Lombardi for having “no audio-visual recall.” He was getting only the bare bones, none of the rich details that make a book sing. How could he build a memoir out of that? At night, unable to sleep, stewing about his dilemma, Heinz came up with the solution, falling back on a structure that had worked for him once before.

This was the progressive narrative technique that he had used for a magazine article on a boxer. Heinz followed Rocky Graziano from the break of dawn on the day of a major fight. The beauty of the progressive narrative was that it provided a natural plot line, established by the minute, the hour, the day. Maybe this is the way I can do Lombardi, Heinz decided. I’ll start the Monday after a game and take it through the next game. What little Lombardi gave him could be supplemented by the players and most of all by Marie Lombardi, his wife, who was much more willing to tell Heinz detailed stories. All of that material could weave through the game preparation chronology. Heinz chose the first Lions game in October for the game, and everything flowed from there.

It was only fitting that Marie came up with the title. She said she loved Vince’s phrase describing his philosophy of offensive football.

Heinz wrote the book in his makeshift den, a bantam-size office that he had constructed off the TV room in a corner of his garage. A radiator warmed him as winter approached. The floors were softened by cork tiles, the walls by Philippine mahogany paneling. There was just enough room for a desk and chair and a small daybed for naps. With his notebooks indexed and laid out before him, he rolled two sheets of yellow copy paper around the platen of his Remington portable and began tap-tapping away. He wrote every day from the week after the game until late December, rarely taking a day off. By then he had finished six chapters—Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. When the season was over, Lombardi came to New York, and together he and Heinz watched film of the Lions game again, going over every play for the final chapter—Sunday.

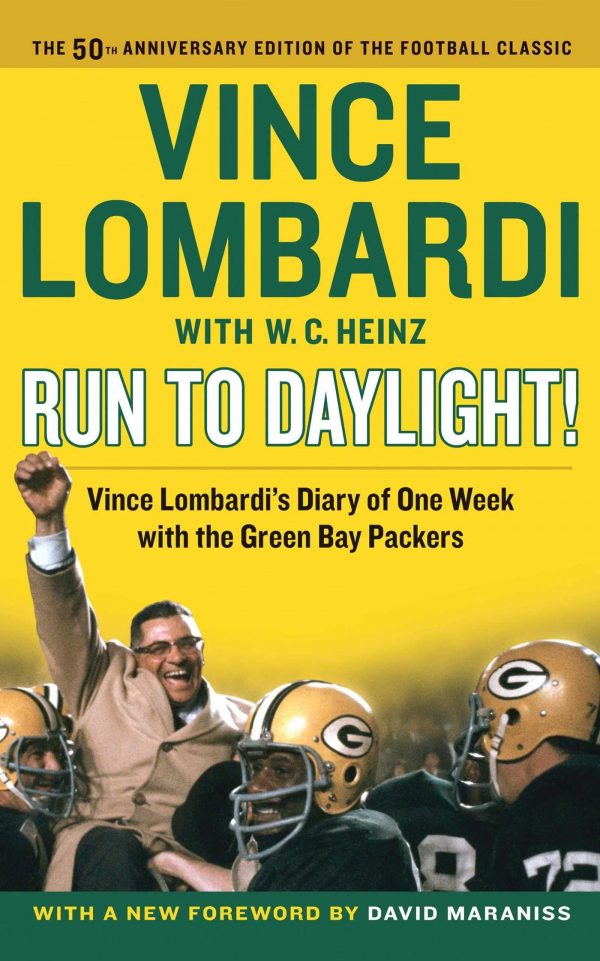

The book came out the following September. Heinz had wanted to title it Six Days and Sunday, but Smith vetoed the idea. “With that title it’ll end up in the bookstores with the biblical tracts,” he said. The publisher, picking up on a phrase that Lombardi was known for using too often at home, wryly suggested, “How about Shut up, Marie?” But of course Marie would not shut up, and the fact that she kept talking to Heinz helped make the book possible. It was only fitting that Marie came up with the title. She said she loved Vince’s phrase describing his philosophy of offensive football. Perfect, the others realized, and here at last was the title for a book that became a sports classic, with twenty-three—no, this makes twenty-four-printings over the ensuing fifty years. They called it Run to Daylight!

—September 2013