“Bad News Bees, huh?” says an early arrival at Municipal Stadium, eyeing the message on a player’s T-shirt.

“The bad news,” the player informs him, “is we’re here.”

The catcher travels by skateboard and lives in a ballpark storage room that he decorated by painting a likeness of Charles Manson on the door. The left-hander claims he drove the nearly 400 miles from Los Angeles in 4 1/2 hours, which is roughly the speed at which cocaine chased him out of the big leagues. The third baseman detests day games, or else he wouldn’t have had to gobble amphetamines to get up for them when he was a Cub.

And you should have seen the ones who got away.

Leading off was Derrel Thomas, who decided he was due for a promotion after so dutifully serving the Giants, Dodgers, and Phillies as a clubhouse lawyer. Exiled to baseball’s bushes, Thomas didn’t want to just play center field for the San Jose Bees; he wanted to manage them, too. It was as if he hadn’t heard the news about himself.

Go ahead and drag out the way his name came up in last year’s double-ugly Pittsburgh drug trial if you must. But the real rap on Thomas concerned the time he once picked to wash his car up the road in San Francisco—during a game. Anyone who appointed him as a leader of men would always have to worry that he might choose the fifth inning to lead them to a hose and a pail of soapy water.

So the answer was no. But Thomas persisted, and when persistence didn’t do him any good, he opted for insolence. As the Bees worked on relay plays, he interrupted Harry Steve, the man who had the job he coveted, and announced, “That’s not the way the Dodgers did it.” Steve responded the only way possible for a manager who is also team president and general manager: he released Thomas. It was not yet opening night.

By the time that momentous occasion arrived, 2 1/2 weeks ago, Mike Norris was at the top of whatever game he was playing. Outwardly, he didn’t appear bothered that he was still dodging the ghosts of his dalliance with nose candy instead of starting another 20-victory season as the linchpin of the Oakland A’s pitching staff. He was the clubhouse clown who greeted everyone with a singsong “Hey-hey-hey-hey.” Nothing seemed to please him more than wandering out to shortstop in his street clothes so he could field grounders with a glove on one hand and his other hand in his pocket. But when the Bees really needed Norris, he wasn’t there.

Maybe he was preoccupied with what the Internal Revenue Service was trying to do to him. Surely there was enough noise about his lack of a driver’s license when he started showing up late for games. “Mike should have been responsible enough to make arrangements for a ride,” Harry Steve says. But Mike wasn’t. The first time, he got docked a week’s pay and the chance to start the Bees’ third game. The second time, Steve kept pushing back the deadline, telling the players they would vote on whether Norris should remain with the team. The extended deadline had been history for 10 minutes when Norris finally walked in the door. When he walked back out, it was forever.

“Right now I worry about him in his everyday life,” Steve says. “Wherever he’s going, he’s got a problem, even if it’s just being irresponsible.”

But there are others among the Bees who know a last chance when they see one, and they are making the most of it. Not only does Steve Howe look like Godzilla against the California League’s predominantly fuzzy-cheeked hitters, he has proved an unerring marksman in the same kind of urinalysis that sunk his career with the Dodgers. Daryl Sconiers isn’t spilling a drop, either, as he tries to rediscover the sweet swing that had the Angels dreaming he would be the second coming of Rod Carew. And what of Ken Reitz, ex-Cardinal, ex-Giant, ex-Cub, ex-Pirate, pedaling around Muni on a girls’ 12-speed bike because the law says he can’t drive and praying that 34 isn’t too old to make it all the way back from amphetamine addiction?

Steve Howe wants baseball commissioner Peter Ueberroth to believe that he is clean, but until recently the commissioner’s office wasn’t returning his phone calls.

Can these Bees really be such bad news?

“If that’s what we were,” Howe says, “we’d paint the team bus black and put ‘F—— Me’ on the front of it.”

The lords of baseball may well be expecting as much, for this is truly the game’s legion of the damned. In addition to their three scandal-tainted stars, the Bees employ three other big league wash-outs, half a dozen Japanese players and a bunch of sandlot escapees who aren’t supposed to have enough talent to play even Class A ball. The result looms as more than a feast for the California League’s grandstand sadists. It is a gamble that could render Harry Steve, and the Bees, past tense.

“If Harry doesn’t win this year,” Howe says, “he’s going to be picking olives in Crete.”

Steve Howe can’t stand still.

He is here to grab a handful of grapes and there to suggest that the Bees include pelvic thrusts in their warm-up exercises. Here to put his cap on sideways and there to tell the Japanese players that they need to know only one word to survive in this country: Budweiser. Here to polish up his statistics (seven hits in 14 1/2 innings) and there to inform the gentleman calling from CBS in Los Angeles, “My goal in life was not to become a professional ballplayer and become addicted to chemicals.”

“Kind of hyper, isn’t he?” Harry Steve whispers.

Hyper and, at age 28, impatient.

Howe wants baseball commissioner Peter Ueberroth to believe that he is clean, but until recently the commissioner’s office wasn’t returning his phone calls. “If they’re going to treat it as a good-boy, bad-boy situation, I definitely don’t fall into the bad-boy category,” Howe says. His case history with the Dodgers and the Twins suggests otherwise, however, so Ueberroth is letting him dangle before approving any deal that could get him back to the big show.

“Put me against any left-bander in baseball right now, and I’ll get a job,” Howe says. “All I ask for is a chance to get a job.”

But the game was always easy for him. It was the rest of life that threw him a curve. Sometimes, when he stops ricocheting around the ballpark and starts thinking, he realizes it. Compare him with Mike Norris, for instance. The Bees threw Norris the same life preserver they threw Howe, but Norris threw it back.

“It becomes a choice,” Howe says. “Sooner or later, you have to take responsibility for your actions.”

The life preserver fits him nicely—so far.

Hold an old-timers’ game in San Jose 10 or 15 years from now and you’ll be able to ring up such fancy names as George Brett, Dennis Leonard, and Jay Johnstone. You might even get lumpy, lovable Rocky Bridges to return to the city where he first said, “I managed good but, boy, did they play bad.”

It is not just that the Bees last had a winning season in 1979; it is that they have lost 259 games in the past three years alone.

The problem is, there might not be a professional team here then. There might not even be one next year. Never mind the covetous glances the city fathers cast at the Giants when they were being shopped around last winter. Never mind the 675,000 people who live within the city limits or the 1.2 million people who live in Santa Clara County. Never mind the high-tech wonders that are worked daily here in the heart of Silicon Valley. This is a dying franchise.

It is not just that the Bees last had a winning season in 1979; it is that they have lost 259 games in the past three years alone. And their attendance shows it. In the league’s largest market, they drew 53,423 paying customers last year, and only two of nine teams did worse. What’s more, the Bees have no big league affiliation to infuse them with playing talent. The closest they come is an agreement with Japan’s Seibu Lions, and the Lions, bless their hearts, are more than an ocean away from such old providers as !he Royals, Expos, Manners, and Angels when it comes to baseball.

Harry Steve knew things weren’t going to improve when the Blue Jays turned up their noses at a chance to put a farm team in San Jose and settled instead on Ventura. “The park there doesn’t even have lights,” Steve says. But he has an idea why it happened: “The last year we had a player development contract, I clashed with someone who’s pretty powerful, a farm director. He wouldn’t have the guts to tell me to my face what he’s been saying, but I’ve heard about it.”

Maybe that makes Steve an outlaw of sorts. If so, he knows how to play the part. There is no modesty when he talks about tracking down Howe at his winter home in Whitefish, Montana. Rather, Steve poses with a cigarette in the corner of his mouth, trying to look older than 30, and says, “It was just a matter of a general manager having enough balls to go after Howe. The A’s got Andujar, the Mets got Hernandez. What’s the difference?”

The difference is that no one ever thought the A’sand the Mets were running halfway houses. With Harry Steve’s Bad News Bees, it was just the opposite. He might as well have said, “Give me your poor, your tired, your huddled masses,” because every vagabond in baseball started calling. Not just the drug cases, but the outcasts like Darryl Cias, the catcher who bounced from the A’s to Italy in one season. And Fernando Arroyo, a pitcher who slipped through Oakland, Detroit, and Minnesota almost unnoticed. And Lorenzo Gray, a third baseman who got pink-slipped by the White Sox after batting nearly .400 in the Pacific Coast League three years ago.

It was a windfall, but an expensive one, considering that some of these characters were going to make upwards of six times the California League’s $300 minimum monthly salary. Steve decided the financial risk was worth it on the grounds that you have to spend money to make money. “I’ve always paid my bills, although sometimes they’ve been late,” he says. “This year, if things don’t work out, they’re going to be later than usual.”

But look at the bright side. If things do work out, attendance will be like opening night’s 4,911 and not like the season low 488. If nobody on the team goes over the wall, Steve might be able to sell one of his stars to a big league team, a deal that would give both the player and the Bees a share of the money. “You look at Toronto,” he says, “and you know they may be only a Steve Howe away from the World Series.”

But do the Blue Jays know it? That is one more worry for Harry Steve, who already has more worries than he bargained for. His biggest one, of course, is managing the team. He thought a proven minor league commodity named Frank Verdi was going to do it, but five days before spring training, the Yankees lured Verdi away with a scouting job.

“I didn’t want to get another manager just to get another manager,” Steve says. “I had handpicked the ball club, and I wanted to hire a guy who would follow through on the plans I had.” He smiles slyly. “Plus I’d used all my money signing players.”

Thus did Steve add another line to a resume that shows no evidence whatsoever of his ever having played pro ball. Even on the sandlots back home in Youngstown, Ohio, he was never much of an infielder. “Decent glove, crummy arm, even worse hitter,” he says. “I always knew what to do, but I couldn’t do it.” No wonder he became a general manager. He was 23 when he dropped out of Biscayne College’s sports administration program to run Macon in the South Atlantic League. Ever since, he has been swimming against the tide in San Jose. And now he is a manager who can’t help thinking he really isn’t doing things the Dodgers’ way, who hasn’t mastered the art of hitting fungoes, who can’t even get thrown out of a game in high style.

“You’re the worst manager in the league,” said the umpire who bounced him in Fresno the other night.

Steve considered the possibility. Then he said, “Well, you’re the worst umpire in the league.”

Obviously, this will take some getting used to.

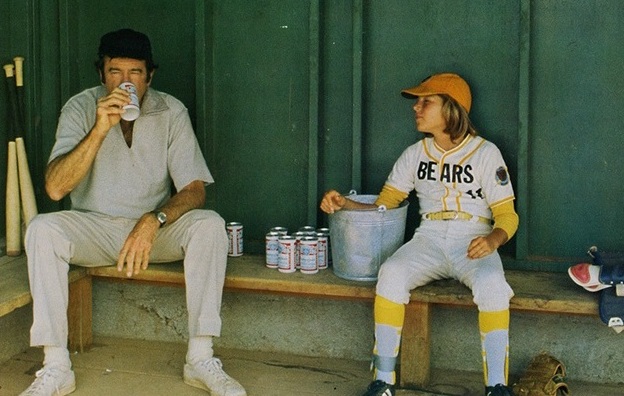

“They tell you you’re not supposed to take the game home with you,” Darryl Cias says, “but that’s tough to do when you live at the ballpark.”

His home is the storage room under the first-base grandstand. He calls it “the Stadium Hilton” even though the do-not-disturb sign hanging on the door was borrowed from a Holiday Inn. The reason he lives there is as easily understood as an empty wallet.

There wasn’t much money to be made when Cias played in Italy last season, and the bright future he thought he had catching for the A’s went up in smoke the year before that. “I hit .300 my rookie year in Oakland,” he says, “and the next spring they wanted to send me to Double A. From what I understand, they thought I had a bad attitude, didn’t want to work. Listen, I’d rather have a drug rap than that.”

Whatever, Cias needed a cheap place to stay. When Harry Steve told him about the two Bees who had lived in the Hilton last season, the thing Cias liked most was that they lived there free. So in he moved. Ken Reitz followed soon afterward, motivated by the lack of a driver’s license, which put him on a short leash. There was a pitcher living with them until he got released, as well as a steady stream of teammates looking for a cold beer and reporters seeking an oddball story. “We threw another mattress on the floor,” Cias says, “and the guy from Rolling Stone stayed the night with us.”

With all the company, Cias decided it wasn’t enough to have the place decorated with a couple of makeshift beds and six stadium chairs propped in front of a portable TV. He rooted around in the remnant bin at a carpet store and found enough scraps to cover the concrete floor. He decorated the walls with a poster for a skin flick called Bubble Gum. He found a neon Coors sign to use as a night light. His most dramatic contribution, however, was to paint Charles Manson’s face on the door.

Cias warmed up for his masterpiece by painting the TraveLodge and Almaden Hyundai signs on the outfield fence. When he started to put a coat of black paint over the Hilton’s drab tan walls, Reitz stopped him and held up a paperback copy of the book Helter Skelter. “Why don’t you paint him?” Reitz asked, pointing at Manson’s wild-eyed mug on the cover. Cias obliged, and a conversation piece was born.

But sometimes, early in the morning, he can’t help wondering if Manson’s wacko likeness isn’t getting to his roommate. “I’ll wake up,” he says, “and Reitzie will be sitting there, staring at it.”

If Daryl Sconiers couldn’t tell where he was by the lack of soap in the shower, he would be able to by the paucity of clean socks and jocks or the lights that make him feel like he’s trapped in perpetual dusk. Even an innocent conversation can serve as a reminder that his next step down will take him out of baseball.

“Where’d you play last year, man?” Sconiers asks the Bakersfield Dodger who has just camped beside him after hitting a single.

“Pioneer League,” the kid chirps.

“Damn.”

That is what baseball has come to for the 27-year-old Sconiers. When the Angels released him last winter, after a season in which cocaine brought him to his knees, there were no takers. “People tell you you’re supposed to be one of the best left-handed hitters, and then something like that happens,” he says. “It gave me a feeling that people were just fed up, that teams weren’t taking risks.”

Sconiers’s campaign in San Jose is to convince the world that he is no risk at all. Part of it is based on the kind of talking that sounds like It comes straight from a therapist’s couch. He thinks back to his three seasons with the Angels and says, “I suffered from belligerent intolerance. I got used to all those luxuries we had in the majors, people offering to drive your car around front and pick you up after the game. I didn’t realize that didn’t have anything to do with reality. I was unbearable, selfish, couldn’t deal with other people’s mistakes. Really. You look up ‘belligerent intolerance’ in the dictionary and you’ll see that was Daryl Sconiers over and over again.”

Maybe insight and humility come when you are forced to live the way he is, in a Holiday Inn, with his wife and child back in Southern California and without a moment’s relief from the fear that this might be the end. “I think I have time to make it back,” he says, “but I don’t have time to waste.”

It is a precarious situation, and there are nights when Sconiers can’t escape it, nights like this one. He strikes out swinging his first time up against Bakersfield, then goes down looking the next time. When the third strike is called, he takes two steps across the plate and slings his bat against the grandstand wall. And then Municipal Stadium closes in on him.

From the third-base seats, a schoolyard taunt: “Throw your bat, Daryl.”

From the first-base seats, a regulation-issue insult: “You’re a bum!”

Back to the third-base seats for a final, withering judgment: “Weak, weak, weak.”

In a ballpark with only 5,000 seats, there is neither the distance nor the dull hum to be found in the big leagues. Every insult is right in Sconiers’s ears, and when he talks back, the abuse becomes louder and more cutting. His best defense is the single he pumps into right field in the seventh inning. But even that backfires when he overruns second base on a bunt and stands helplessly between second and third, waiting to be tagged out, waiting so long that he might have time to compose what he will say the next afternoon: “Years from now, I want people to tell you, ‘Daryl Sconiers, he endured.’”

It is a wonderful thought, and yet it sounds all wrong. When you’re at a revival, you don’t expect to hear an epitaph.