“Tell the guys in the crew to use my trailer while I’m gone.” It’s a star’s trailer, parked outside War Memorial Stadium in Buffalo, New York, Glenn Close is shooting The Natural with Robert Redford and Robert Duvall. It’s a luxurious trailer, with a small bedroom, a well-stocked kitchenette, a cozy living room, but Close is determined to be the kind of star who doesn’t put on airs.

“I’ll tell ’em,” says Wilford Brimley, a grizzled old character actor who plays the team manager in this adaptation of the Bernard Malamud baseball novel, “but they won’t do it.”

“Why not?”

“They just won’t, that’s all,” Brimley says bluntly—he’s been in movies long enough to know; he understands the unwritten codes.

Close and Brimley have been buddies since day one—“She’s my pal and I love her,” he says gruffly—but now he’s a bit exasperated. What kind of nonsense is this?

“Well,” Close announces firmly, “they’ll use it if I tell them,” and she climbs down the steps of the trailer and marches past Brimley in the direction of the crew’s quarters. She comes from an upper-class New England background, and it’s sometimes unclear where democratic instincts end and noblesse oblige begins.

Close not only likes to feel like one of the boys, she wants to think of herself as part of a generation. Over and over, her conversation comes back to her professional peers, performers like Meryl Streep, Mary Beth Hurt, Kevin Kline, Bill Hurt, Mandy Patinkin, JoBeth Williams—and one of the characteristics she shares with them is a desire to work onstage as well as on film: This is the first generation of actors to make a full-scale commitment to a dual career.

“l’m so much more insecure in films. Everything is in such tiny segments it’s nearly impossible to get a sense of the whole.”

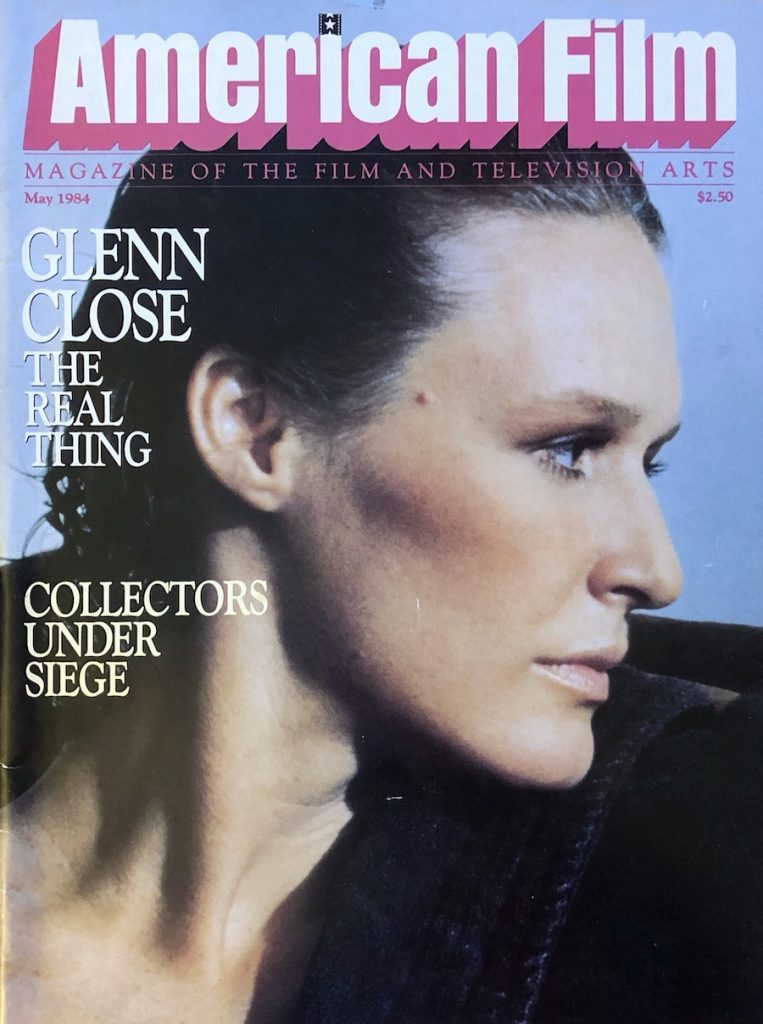

In films, Close made an astonishing debut as Jenny Fields, Garp’s mother in The World According to Garp (winning an Oscar nomination) and appeared opposite Kevin Kline in The Big Chill (another Oscar nomination) and Robert Duvall in the recent Stone Boy. She landed one of the most coveted female movie roles of 1984 when she was asked to play Robert Redford’s first love in The Natural. On the New York stage, she’s played everything from P.T. Barnum’s sexy wife in Barnum to an angelically androgynous woman who disguises herself as a man in The Singular Life of Albert Nobbs. She landed the most coveted female stage role of 1984 when she was asked to play opposite Jeremy Irons under Mike Nichols’s direction in Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing. (On top of all that, she’s appeared in a number of highly acclaimed television movies, and has even found time to sing the National Anthem before several Mets games at Shea Stadium.)

“Some of the differences between film and theater are obvious,” she says. “To project a character like Jenny in a play, for instance, you’d have to be larger than life. But to do that in a movie would be too stagy. You have to bring it down, be more subdued, find the right level of energy. You have to find a balance between the character’s aura and the intimacy of the camera, and it’s much harder to work with a camera than with a live audience.

“But it’s much more than that—l’m so much more insecure in films. Everything is in such tiny segments it’s nearly impossible to get a sense of the whole. There just aren’t any guideposts—you never know what your performance is like. I may think I’ve done well or done badly, but what I think doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with the result. It makes me nervous to have my entire performance come out of the editing room. You’re at the mercy of so many different things and people. And you never know if the scene you’re working on is a crucial scene, or a fallout scene, or what. I hate that kind of limbo.”

“In theater,” she continues, “you have at least four weeks of rehearsal; you can explore your character, you can discover her emotional landscape. Even then, you’re lucky if you’ve found the starting point by opening night. But you can continue to grow if you’ve at least found the outline. It’s such a luxury to have that preparation. On my next film I’m going to fight for a rehearsal period.” You can see where Jenny’s determination came from.

Close wanted to be an actress “for as long as I can remember. As a child, my most vivid fantasy was to persuade Walt Disney to put me in movies like Old Yeller.” Born in 1947 in Greenwich, Connecticut, a town her ancestors helped establish in the late 1600s, Close comes from a traditional New England family—traditional, that is, in the double-edged New England sense, both aristocratic and eccentric, both sedately down-to-earth and unconventionally idealistic. Her father, an eminent surgeon, cast aside his lucrative Greenwich practice to set up clinics in Switzerland and the Belgian Congo, and now runs a country clinic in Wyoming.

“It was a privileged life,” she admits. “We lived on this huge chunk of land, my grandfather’s estate. I was this wild little tomboy. But it was very isolated also. My parents were never really interested in the social or material side of life in Greenwich. They quit the country clubs and never went sailing or to dances or that kind of thing. They were of that heritage, but not in it.” She describes her upbringing as “a kind of limbo,” the very word she uses to characterize the insecurity she hates in filmmaking.

Another way her parents flouted upper-class New England traditions was to raise the four children themselves. No nannies for their kids. But when Close’s father first went to Africa in 1960, her mother frequently “commuted” and the children were put in Swiss boarding schools for two years. And when her parents finally packed up and actually moved to Africa, where they stayed for sixteen years, the children spent most of their time in various boarding schools or with their grandmother. Close talks reluctantly about those years—it’s obviously not one of her favorite memories. “I think when you’re growing up,” she says slowly, “and your parents are away from home that much, you can’t help but feel a little rejected. I’ve spent most of my life trying to like myself better.”

“Although”—she goes on with a nervous laugh and a mezzo-mezzo wave of the hand—“that’s always a little suspect.” She falls silent, tries to pass it off with a shrug. “l remember crying, yes, but I always felt that when my parents were there they really loved me.” She pauses once more, and one can’t help but remember that her long relationship with Broadway star Len Cariou recently came to a painful end, something she doesn’t want to talk about at all.

“And anyway,” she says, laughing, “if my parents hadn’t been away so much, I wouldn’t have gotten to go to Rosemary”—Rosemary Hall, an upper-crust girls’ boarding school in Greenwich, where, perhaps in reaction to her loneliness, that childhood fantasy of becoming an actress turned into an adolescent passion. In fact, she and several of her friends formed an ensemble called The Fingernails, the Group With Polish, and put on several of their own shows, culminating in a senior-year production of Romeo and Juliet, in which, her versatility already evident, Close landed the role of Romeo.

After a couple of years touring—with Up With People, she confesses sheepishly—Close enrolled at William and Mary and majored in drama (there was a brief marriage during this time that she won’t discuss). Encouraged by her teacher and mentor, Howard Scammon, she graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1974 and headed for New York. Within months, she was hired by director Hal Prince to play a small role in the prestigious Phoenix Theater’s production of William Congreve’s Love for Love and to understudy the show’s star, Mary Ure. “With only one preview left before opening night,” Close recalls, “Hal dismissed Mary and told me I was taking over the leading role. I’d never even had an understudy rehearsal.”

Regional theater roles in King Lear, The Rose Tattoo, and A Streetcar Named Desire soon followed, then a return to Broadway as a princess in Rex (Richard Rodgers’s last musical), a villainous Irene St. Claire in the Sherlock Holmes thriller The Crucifer of Blood, and the feisty Charity Barnum in Barnum. Glenn Close was not exactly becoming typecast.

When she heard that director George Roy Hill had seen her in Barnum and was considering her for a role in the film version of Garp, she assumed he had her in mind for Garp’s wife. But as Hill recalls, in her first appearance in the play Close was on an onstage box, completely motionless; so convincing was her performance that he mistook her for a mannequin. It was that “charged stillness” that led him instantly to think of her as Jenny, for although Garp’s mother is in some respects a wacky dynamo, even more crucial to her character is a kind of serene self-possession.

In Garp “some people thought I was an older woman made up to look younger, rather than vice versa,” Close laments. “In some ways, it’s easier to act a 158-year-old woman than a 58-year-old woman—58 is a very subtle age—my mother is 58.” But the astonishing thing about her performance, the quality that won her the Oscar nomination and that resulted in a flood of offers, wasn’t so much the ease with which she aged 30 years in two hours as the skill with which she conveyed Jenny’s spiritual growth, from eccentric whimsicality to mature determination.

Although Close is grateful to Garp for giving her an entree into films—“Everything since then has been Garp fallout”—she is concerned that nearly all the film roles offered her have been what she calls “daughters of Jenny.” “I haven’t been typecast as an older woman, thank God, but they’re basically the same type of woman—motherly, strong, serene.” Suddenly the New England composure falls away and she’s furious, recalling an article in a national magazine which said that although she has “an incandescent sensuality” onstage, in films she can’t seem to get beyond “an Earth Mother calm.”

“To do the real thing—with all the delicacies, all the intangibles—you can’t look like you’re working at it. I don’t like performances where I can see the technique.”

“What do they expect when that’s all I’ve been asked to do? I like my role in The Natural,” she says, “but in a way I’m just a fantasy figure for the Redford character.” She adds, with a touch of exasperated sarcasm, “You know: ‘Wouldn’t it be nice if all women were like that, so loving, so strong, so ready to take him back?’ I want to break out of that Jenny trap.” When she first read for the role, in fact, she went to a hairdresser “and came out looking like Olivia Newton-John. But I felt so uncomfortable I did my second reading in blue jeans, with no makeup or anything, and I guess that did it.” Unfortunately, she had already signed to do a film version of Henry James’s The Bostonians at the same time, but Redford wanted her so badly that after extensive negotiations, she was finally released from that obligation.

“I hope The Natural is the end of the Jenny arc in my career,” Close says. “I feel I have a much greater emotional range than I’ve been able to show in films so far. I’ve only made four films, and I don’t feel I’ve done anything but scratch the surface.”

Within a few minutes the same actress who’s been talking with frustrated eagerness about her aspirations is biting her lower lip, staring at her hands, explaining how agonizing it is to prepare for a role. “In the first couple of weeks of rehearsal, I’m in a state of total panic.” She’s more familiar with the process now; she can laugh at herself a bit. “I mean I always tell my friends this time it’s really going to be a disaster; I’m sorry I even tried this one. But they know my pattern by now. ‘That’s what you said last time,’ they tell me.” She imitates their weary tone.

Harold Guskin, an acting coach in Greenwich Village she’s been working with for the last couple of years, helps her pull out of it. “It’s not really a technique, but he helps me get the words off the page. I sit there, all hunched over, and start by simply saying the words out loud, just breathing them. There aren’t any limitations; I’m free to make a complete fool of myself; the only rule is just to get it out. Then he starts prodding me, asking questions I couldn’t ask by myself. I’ve found that the important thing is to discover the simple reality of where my character has come from. I don’t mean in any deep psychological sense, just where she was a few minutes ago, what’s on her mind right now—all in a very precise, immediate way. If I can find that kind of simple reality, rather than imposing a lot of ‘interpretation,’ it gives impetus to an entire scene; I feel I can roam all over the place.”

“But it’s not as easy as that,” Close goes on. “First you have to make yourself vulnerable, and that’s the scary part. To do the real thing—with all the delicacies, all the intangibles—you can’t look like you’re working at it. I don’t like performances where I can see the technique. You have to find the emotional center instead, and that means being open, taking chances. You never know when the flip is going to come; you just have to trust the process. All I know is that if I’m working hard, I haven’t got it yet. It should be easy, it should be simple—even if the simplicities are in layers on top of one another, like DNA. When I finally find the character, that’s the payoff for all the agony. When the character finally begins to crack the shell of her egg, that’s the joy.”

As much as any other actor working today, Close genuinely responds to the other performers, acting with rather than at them (her two Oscar nominations, fittingly, have been for supporting actress). She combines this rare gift with an ability to convey apparently contradictory emotions simultaneously. Other actors can whip up an angry frenzy on cue, but Close can also show us the regret—or the insecurity, or the tenderness—that underlies the anger. This accounts for the fact that she so often seems a paradoxical figure—Jenny, tough yet elegant, blissful yet determined, wacko yet genteel; or Annie in The Real Thing, at once raunchy and ladylike, daft and no-nonsense, glamorous and dowdy.

“The Natural is my fourth film, but I didn’t learn until Redford that you don’t have to use all your energy on the master shot.”

There’s an emotional radiance in her work that has in fact become the Glenn Close signature. When her performance fails, as it does in The Stone Boy—an artsy, mannered tearjerker—it’s because she reaches so hard for intensity she forgets to relax as well—and the emotion seems abruptly triggered by cues rather than spontaneously released by experience.

“Preparing for a role,” Close says, “is like hearing a tune in your head but when you try to sing it out loud you can’t quite get it right. What I aim for is to reach that point when the tune I sing perfectly matches the tune I hear in my mind.”

Glenn Close is sitting in the stands, watching them film one of the final scenes in The Natural, talking about the directors she’s worked with. In a world in which insincere gush is the lingua franca, she’s candid in her appraisals. “Of course, the director always has the entire picture in his head,” she says, “but the degree to which he explains it to you varies widely.” Of Barry Levinson, the director of The Natural, she says: “I feel like he knows what he wants and what he’s getting—it’s just that he’s not letting the actors in on it. I’ve felt very insecure throughout the entire filming, insecure and manipulated.” Of Lawrence Kasdan, The Big Chill: “He was somewhat more articulate” and provided a four-week rehearsal period complete with ad-libs and improvisations, but once the script was set he became “strict, almost stubborn. In a way, he was too articulate, which is a way of being inflexible.”

As for Hill, he was “medium articulate,” a condition Close seems to prefer. “We had a rehearsal period for Garp,” she recalls, “and mapped out five major age changes for Jenny. It was invaluable because, of course, the film wasn’t shot consecutively and the psychological shifting of gears would have been impossible otherwise. With that advance preparation—getting a sense of Jenny as a whole—I could go to a scene five or six weeks later and instantly know where I was. By the end, I felt I could do her in any situation.”

Redford strolls onto the field in his baseball uniform to shoot a scene, and Close says she learned a lot from him as well. “The most important thing he taught me was a sense of relaxation. The first time I watched him work, I noticed that he was much more interesting, more specific, more detailed as the camera got closer and closer. The Natural is my fourth film, but I didn’t learn until Redford that you don’t have to use all your energy on the master shot; you can use the master to feel out a scene. He also taught me that you don’t have to use all your energy to make a whole scene work every take; you can work for just one moment. There are so many takes, they can pick one moment here, one moment there, and put them together in the final cut. It’s not the most comfortable way for me to work, coming from theater, but it was crucial to learn. The trouble is, what if my moment isn’t the director’s moment?” She laughs. “Some actors, of course, make it work so that you have to use what they want; they just don’t give you anything else.” You can see that the idea tempts her.

But then she becomes thoughtful, almost troubled—there are shadings in her personality she’s unable to hide; in fact, she sometimes seems permanently condemned to a condition halfway between the New England work ethic and neurotic insecurity. “I’ve felt unformed all the way through The Natural,” she complains, “vulnerable to pulls in all kinds of directions. I’ve never really felt I have a sense of focus for my character.”

Working with Mike Nichols on The Real Thing, though, that’s been a delight. “He’s the best I’ve ever worked with. He deserves to be a legend. He has such an innate understanding of the creative process, how you have to let it happen. You know what I like best about working with him? The way he says, ‘Don’t worry, there’s time.’ I’ve been given to understand by Mr. Nichols that I can come up with the goods.”

A lot of people think she can—including all her directors, who praise her in tones ranging from admiration to awe. And Howard Scammon, her former teacher, suggest that superb as she’s been, all that those film roles have shown is the “controlled side” of her personality. “But she has so many more facets than that. Wait until somebody gives her a voluptuous, lusty role!”

“Hey, Glennie,” one of the crew members calls out from the batting cage during a break in the filming. “Want to hit a few?”

Without saying a word, she jumps out of her seat, climbs over the fence, runs onto the field, picks up a bat, stands in the batter’s box, faces the pitcher, and waves the bat solemnly back and forth, just like she’s seen the ballplayers do it. Glenn Close is ready to hit.