Almost no one knows that twenty-eight-year-old Melanie Oakley* is gay—not her family, not her colleagues at the law firm where she works as a legal secretary, not her friends in the Queens neighborhood where she grew up and still lives. “Everything in my life is secretive,” she says. “I’ve known I was gay for eight years, and I’ve had the same lover for over a year now. But I don’t know if my family could handle it, and I live at home. I don’t want to throw anything in their face.” Oakley pauses, then adds fiercely, “There are people who want me to come out, but I can’t, and I don’t think there should be pressure. It’s my life, and no one else can live it.”

[*Names and identifying details in this article have been changed.]

Vivian Shapiro, on the other hand, is a forty-three-year-old Manhattan businesswoman and activist who came out sixteen years ago. As she sees it, “The only reason to stay in the closet is if you feel less equal and ashamed of who you are. To me, the price you pay for the closet is lack of freedom, lack of dignity and lack of self-respect.”

Clearly, even in New York in the 1990s, the decision about whether or not to go public as a lesbian is fraught with risk. This is not the 1960s, when, for a moment, coming out was hailed as a celebratory event, the apotheosis of women’s liberation. Today, renouncing all the years of near-invisibility, many lesbians are responding to a different social and political climate by creating a new sense of community, built around pressing concerns of the day—such as lesbian parenting, domestic partnership and AIDS.

Even in New York in the 1990s, the decision about whether or not to go public as a lesbian is fraught with risk.

AIDS, in particular, has mobilized the gay and lesbian community to form powerful action groups, such as ACT UP; the group, with its large female contingent, has given gay members a strong sense of political muscle and collective identity.

At ACT UP demonstrations, lesbians who are in the closet may feel safe enough to come out. But not everyone is ready to, and for good reason. In an age of heightened homophobia, when violent incidents against gays are rising dramatically, and jobs, homes and personal rights can still be arbitrarily taken away, many women are more afraid than ever of revealing who they are. Joan Nestle, a forty-nine-year-old lesbian historian, sees the dilemma in context. “This is a time of living on the edge for us gay women,” she says, “an important time for us to decide how best to live our lives and not to betray ourselves in the face of public attacks on homosexuality and all the conflicts of our society. The new wave of activism is thrilling, but it’s also sad because it’s built on violence and death.”

There are an estimated 500,000 lesbians in the New York area—one in ten women is believed to be gay. Particular neighborhoods—like Park Slope, in Brooklyn, and Cherry Grove, in Fire Island—claim thriving, long-established lesbian enclaves, but, in general, the lesbian “community” is a diffuse one. “We really are everywhere,” says one young gay woman from her home in Brooklyn. “We are the investment bankers, the doctors, the artists, the mothers with young children.”

Tucked into the folds of the city is an impressive lesbian subculture: a health center, the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center, professional and sports organizations, gay crisis groups, service networks for both the elderly and the young, the Harvey Milk High School for gay students, bars and clubs, publications (like Womanews), even a lesbian “herstory” archive to record the milestones of their communal lives.

Those who want to can lead their whole lives inside this subculture. Since she came to New York from Santa Fe one and a half years ago, eighteen-year-old Garance Franke-Ruta has become friendly with only three or four straight people and says she “likes it like that.” Bright, brash and articulate, Franke-Ruta works at odd jobs, such as selling clothes or artist modeling, and, in flamboyant outfits she’s made herself, visits clubs like Cave Canem, which is frequented on certain nights by the so-called “lipstick lesbians” and “glamour dykes,” and Mars, in the West Village, where she works as a go-go dancer every Sunday night. She’s also active in a number of political organizations, such as ACT UP, the Reproductive Rights Coalition, the Women’s Health Action Mobilization and Art Positive, a group formed in response to homophobia in the press and the arts community and also to attempts in Congress and the NEA to restrict funding for arts projects with gay themes.

Inevitably, younger gay women tend to take the existence of a supportive community for granted. Twenty-two-year-old Amy Webb lives with her lover of two years, Joy DeVincenzo, in an aura of cozy domesticity that conjures up a conventional world of monogamous commitment. They consider themselves married and are widely accepted as such among their friends. They plan on having a baby within a couple of years—to be conceived, they say, laughing, with the help of a mail-order artificial insemination kit. Petite, vivacious Webb, a student at New York University, is eloquent about the importance of lesbian political power. She has an easy confidence in her sexuality as she hugs DeVincenzo and laughingly talks about the male students who come on to her, unaware that she’s gay.

Meanwhile, forty-four-year-old DeVincenzo, taciturn and more guarded, is a self-described “old-school dyke” who dressed in drag in the Sixties, hung out in bars like the Stonewall and has spent over twenty years living with the terror of street harassment and arrest. “They do as much as they can get away with,” she says from bitter experience. “If I’m with someone who looks like me, it’s OK, but if I’m with someone feminine who a man would be attracted to, then there’s always trouble.”

“Joy has put up with a lot of abuse, and many people my age don’t really appreciate what her generation made possible for us,” Webb says.

Coming out of the closet means “taking all the values you were raised with and made to believe you would have—a house, a husband, a child, whatever the values your parents have—and realizing it’s not going to happen like that for you

What women like DeVincenzo made possible was for other lesbians to lead their lives, not merely out of the closet, but openly in the straight world. Vivian Shapiro, is a vice president at David Geller Associates, a print media advertising firm, has no secrets at work. She has reached a position where she could help organize a black-tie dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria to raise funds for the Human Rights Campaign Fund (a progressive organization that supports AIDS research, among other things) and persuade her heterosexual colleagues to buy tickets to it. Shapiro says a return to the closet is unthinkable. “I would be saying that who I am isn’t good enough.”

In Shapiro’s view, the greatest barriers to coming out are internal ones, basic assumptions about life that have to be reexamined. Coming out of the closet means “taking all the values you were raised with and made to believe you would have—a house, a husband, a child, whatever the values your parents have—and realizing it’s not going to happen like that for you. It’s isolating to know you’re not like everyone else and that your life won’t be like theirs either.” She adds, “You either get over it and live a full life, contented life, or you maintain that homophobia and never really come out.”

What most do is come out to a certain degree. Annette Hauser, a soft-spoken, twenty-nine-year-old teacher in Queens, is out to her friends but keeps her sexual identity secret at work, “because of the unfortunate stereotypes of gays and lesbians as child molesters.” Thirty-three-year-old Jan Murray, a vice president in a Manhattan bank, says she, too, is in the closet at work because her bank is so homophobic and because “a lot of the bank’s business comes through socializing, and I’m afraid there would be a perception that, socially, I wouldn’t be presenting the image the bank wanted.”

So each day these women put on their publicly acceptable, sexless faces before arriving at the banks and law firms and ad agencies and schools where they work. They keep the private, sexual areas of their lives damped down, hidden away. If they talk about their weekends or vacations, it’s with swift references to a “roommate” or a “friend.” There are rarely any smiling photos on their desktops, and working friendships are guarded. “Often, when you get friendly with someone and then they find out you’re a lesbian, they’ll reevaluate the whole relationship, pull back and think, That time she put her arm around my shoulder, was she comforting me or trying to make up to me?” says Hauser.

It doesn’t get easier with age. “The more power you have, the more you’ve got to lose,” says one woman in a senior position in the New York media. “And the older and more corporate you get, the less likely it is that AIDS, or anything else, will give you the freedom to tell others who you are.”

For some, coming out has always been unthinkable. Oakley is determined that neither her family nor her old friends find out her secret. “We’re at an age where a lot of them are married,” she says. “They talk about their kids and go shopping with their husbands, and it’s hard to relate to them because we don’t have anything in common anymore.” Oakley’s particularly worried about her parents: “What if my family disowns me? My friends may not be around in two years.”

For lesbians as well as gay men, AIDS has become a watershed—the measure of how destructive concealment can be.

At the Bronx police precinct where twenty-three-year-old Liz Harris works, the atmosphere bristles with homophobia. She knows she could not continue working there if her colleagues ever found out that she was gay. Ironically, Harris says, a lot of cops, especially women, are gay. “I’d say as many as 40 percent of the women could be, but it’s one of the great taboos to admit it,” she says. “The men, especially, are so anti-gay and they’re such nasty gossips, they’ll badmouth anyone, especially women. And all the guys I work with can’t wait to cheat on their wives….Maybe 5 percent don’t.”

Harris who has short hair, a stocky build and describes herself as “athletic-looking,” thinks people suspect that she’s gay. “One guy asked me out,” she says, “and when I wouldn’t go, he started telling everyone I was a dyke. They’ve even written slogans about me on the precinct walls. I think a lot of them are jealous of me because I moved up fast in the precinct.” It’s only because Harris wants to continue moving up that she stays silent. “One day, I’d like to be a detective, and if I were out, I’d definitely not get promoted,” she says.

Women in situations like this insist on their right to secrecy. As Harris says, “Coming out should be an individual choice, like abortion. I’m a person, and I don’t want to label myself. Why do I have to come out?” The reason, say activists, is the enormous price that must be paid for secrecy. Lesbians who work within the community document that price in startling statistics relating to alcohol and drug abuse, even suicide.

To lessen feelings of isolation, some gay women form social groups, often centered around their careers. Each organization arranges monthly get-togethers for drinks or dinner, either just to meet or to hear guest speakers. At Christmas they hold a giant party together, and in the summer, a picnic in Fire Island. In true New York fashion, these social occasions provide the perfect backdrop for networking. “Many gay people seeking personal professional services would rather do business with other gay people,” says Connie Cohrt, a member of the board of directors of the Greater Gotham Business Council, a kind of gay chamber of commerce.

Jan Murray says that through the New York Bankers Group, she discovered other lesbians working in her company. Now they sometimes get together for a discreet lunch in the cafeteria. “Meeting other women has made an enormous difference to me,” she says. Her membership in the group has brought her nearer to coming out—in a carefully orchestrated way. “I became president of the group for a while, which wasn’t very anonymous. But I made a decision about what risks I was and was not willing to take. Sometimes I think I’m going to tell my boss—I think it would be helpful to come out selectively—but a broad announcement would not be a good idea.”

It’s the broad announcement that’s the hardest thing of all. But while acknowledging that, activists maintain that it’s the only way to increase public recognition of lesbians. “Visibility is a critically important thing—to let a larger society know we’re here and to articulate our own needs to our sisters,” says Virginia Apuzzo, a leading spokeswoman for the lesbian community. “If we’re not visible, we’re living life on parole, and what kind of life is that?”

Apuzzo, now forty-eight years old and vice chair of Governor Cuomo’s AIDS advisory council, became visible in the Sixties. She was one of a wave of feminists who made their sexuality a central part of their political emancipation. Eloquent and indefatigable, she is a former executive director of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force and is considered the unofficial leader of her community—a champion of myriad causes, such as gay and lesbian civil rights. She was one of the first lesbians to become involved in the fight against AIDS (and instrumental in getting its name changed from the punitive Gay Related Immune Deficiency [GRID]) and one of the first lobbyists to demand more federal involvement.

Over the years, other prominent women have also come forward on behalf of gay rights. New York criminal court judge Marcy Kahn, one of the founders of the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center on 13th Street, used the occasion of her induction in 1987 to pay tribute to her “life partner,” Diane Churchill, and subsequently said she hoped her visibility would “make it clear to young girls struggling with life choices that they have a lot of options open to them.” And Lee Hudson, long active in city government on behalf of gays and lesbians, was, in part, responsible for persuading Ed Koch to create the Mayor’s Office for the Lesbian and Gay Community shortly before he left city hall. This move put gays and lesbians on the same footing in city government as Asians, blacks and Hispanics; Mayor Dinkins, in a postelection position paper, says the office will be “strengthened to better represent lesbians and gay men in the city’s bureaucracy.”

With these kinds of advances through the Eighties, as well as the passing of some gay rights legislation, the old-guard activists have now joined forces with their younger counterparts to concentrate on newer issues. A top priority: AIDS. For lesbians as well as gay men, AIDS has become a watershed—the measure of how destructive concealment can be. “When people have to confront their parents with the facts that they’re gay and dying of AIDS both at the same time—that’s a real mark of how tragic secrecy is,” says Hudson.

For a long time, AIDS was a polarizing issue among lesbians: While some threw themselves into helping with the crisis, others backed away, nursing the raw resentments against men that have historically led to lesbian separatism. “The feeling was, ‘Where were the men when we needed them in the women’s movement, to fight for our rights,’ ” says a former volunteer at the Gay Men’s Health Crisis. “AIDS was yet another issue that made gay women feel invisible.”

But the bitterness has softened. Most gay women in the city have been touched by the death of male friends, and, increasingly, even though lesbians are termed a “low-risk group,” numbers of them are being diagnosed as HIV-positive. Most of these cases are the result of IV drug use or heterosexual sex, but a few woman-to-woman sexual transmissions have been documented. As ACT UP members wearily point out, there are no low-risk groups, there’s only low-risk behavior.

Gradually, male and female homosexuals have formed a united, compassionate front to fight AIDS, and ACT UP has played a large part in bringing them together. Its angry, relentless lobbying of federal and city health agencies has forced changes in policy and freed medications from protracted FDA trials for use by desperate patients. Even though ACT UP is dominated by men, its raison d’être has prompted lesbians to make their presence felt. About a quarter of the three to four hundred members who attend the packed weekly meetings are women—straight, bisexual and gay. “ACT UP has changed everyone’s life who has come in contact with it,” says young Garance Franke-Ruta. In particular, “it has revitalized the gay and lesbian activist movement.”

One of the incidental changes ACT UP has brought about has been to teach lesbians how to fight for political prominence in the organization. Older members, like Maxine Wolfe, politically active for over twenty years, had fought for this within the mainstream women’s movement. “I was always made to feel invisible in the heterosexual women’s movement,” says Wolfe. “The only way l was visible was when I was put into the category of ‘queer’ along with gay men. My political sense is that you’ll get called a dyke anyway if you are an assertive woman. It has taken us a long time to persuade people that lesbian issues are fully as important as, say, abortion.”

Today, issues such as lesbian parenting and domestic partnership are far more important to lesbians than abortion is. And those who might be reluctant to join in ferocious political action are quietly working to get their rights to a full family life recognized—legally and socially. As Hauser puts it, “When you’re a lesbian it’s a political act to walk down the street and hold hands with your lover.” So seeking legal recognition as partners and parents is a major political rite of passage.

“When we can all be a community,” she says passionately, “when we’ve moved away from our own hatred of ourselves, then we’ll have really gotten something good.”

In the wake of the Kowalski-Thompson domestic partnership case (see sidebar below), more and more gay women, by drafting powers of attorney, drawing up wills and appointing their partners as their designated surrogates, are acquiring the legal status needed to inherit property, collect insurance and make decisions for their partners in the case of accident or death.

These issues become more pressing as increasing numbers of lesbian couples become parents. In recent years a lesbian baby boom has taken place in New York, and along with the so-called “baster babies” (conceived through artificial insemination) has come the necessity to come out—not just to family and friends, but in an official, contractual way as well.

“By the time your baby is born, you have already come out at least forty times—to your gynecologist, the hospital, to your Lamaze class and on and on,” says one lesbian mother. “You have to come out to your family, too, because kids need grandparents and aunts and uncles. There is no way to become a closet lesbian mother.”

For those who have already surmounted the obstacles of finding sperm donors, gaining permission for their partners to be with them in the delivery room and finding a sympathetic pediatrician, infancy may still prove to be the easiest part of the parenting journey. When the children reach school age, gay parents confront the hostile attitudes of other parents, teachers and even their own children—particularly when the mothers used to live with men.

But it needn’t be so awful. Vivian Shapiro says that in the years she spent as the co-parent of her ex-lover’s daughter—in high school when the two women met—she never experienced this kind of opposition. They raised Sheila in their Upper West Side home, in an atmosphere of shared responsibility, where everyone, from the local shopkeepers who knew them well to the women’s families, accepted the situation. So did Sheila and her friends. Describing this kind of acceptance, Shapiro laughs and tells a favorite story about a boy, a friend of the family’s, who also lived with two gay women. One year when he went to boarding school he was asked if he came from Queens. “No,” he replied with a smile. “Lesbians.”

For women like Shapiro, this kind of acceptance has always far outweighed the fears and difficulties of coming out. For women like Annette Hauser, it’s a goal to work toward one step at a time. “When we take those steps and come out to people, we’re empowering ourselves, rather than always wondering and fearing what might happen if people found out,” she says. And that’s what keeps Melanie Oakley hoping the time will come, even for her, to leave the closet once and for all. “When I’m ready to tell people, I will, and I think I will be one day,” she says. “I want my parents to know. I do want to share, and in time, when I’m ready, they may be, too.”

Shapiro feels strongly that as each person finds the courage to come out, the community is strengthened. “When we can all be a community,” she says passionately, “when we’ve moved away from our own hatred of ourselves, then we’ll have really gotten something good.”

The Bar Scene

Over the years, lesbian social life has centered on such places as Identity House, the Universalist Church on Central Park West (where older gay women hold regular meetings), the Mother Courage restaurant in the Village, the Women’s Coffee House and the Women’s Liberation Center.

But the bar scene has been a constant factor. Joan Nestle, founder of the Lesbian Herstory Educational Foundation, describes it as “a wonderful theater that forms your sexual and political self.”

From the Thirties through the Sixties, bars were the only places where lesbians could meet. At great risk of harassment or arrest, lesbians would go to the Village, where most gay clubs were. Those in drag were routinely beaten up or arrested and charged with transvestism. “The feeling of danger made the contact a little more frantic and exciting,” says one visitor. Some of the popular venues: Kookie’s on 14th Street, Café Bohemia on Barrow Street, the Sea Colony in Abingdon Square (dancing in the back room). Uptown in Harlem, black and Hispanic lesbians frequented their own bars, such as Snookie’s, African Queen and Mahogany.

The bars of the Seventies mirrored the more assertive times. One of the best-known was Bonnie and Clyde’s, on West 3rd Street, which had a predominantly lesbian-feminist clientele. Peeches, Cherchez Ia Femme and SheScape (later accused of being racist) thrived. Many were bright and garish, reflecting lesbians’ desire to throw off their secrecy. In 1975, Sahara opened in the heart of the Upper East Side, holding celebrity-studded fundraisers for gay causes and sympathetic politicians.

In these more staid times, many bars have closed because of financial pressure, and gay women have had to seek out alternatives, like the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center. Many of the glitzy “girl” bars of the mid-Eighties are gone. But their philosophy—that lesbians can be glamorous—still lives on certain nights at Cave Canem, in the East Village, and Mars. And for the old guard, there is still the venerable Sheridan Square hole-in-the-wall now called Duchess II (which started in 1974 as the Duchess, and then for a short time was called the Grove Club) and the tiny Cubby Hole, which became briefly notorious when Sandra Bernhard told David Letterman that she occasionally visited it with Madonna.

Milestones

The history of New York lesbianism over the past thirty years falls, roughly, into four phases: the early search for social acceptance; the heady, angry radical politics of the late Sixties and early Seventies; the solidifying of a citywide (and national) gay and lesbian community in the mid- and late Seventies. And in recent years, political activity has focused around legal recognition of lesbian relationships, the fight against homophobia and AIDS, which has galvanized gay men and women into fighting for firm legal and constitutional rights. Some historical highlights:

1964 The Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), the first civil rights and social organization for lesbians (founded in San Francisco in ’55 and in New York in ’56), held its first biennial convention at the Barbizon Plaza Hotel. Many founding members are now in their sixties and seventies.

1969 The Stonewall Riot, which, some say, started when a cop hit a gay woman. This was the event that started the contemporary gay liberation movement.

1969 Betty Friedan, then president of NOW, called NOW’s lesbian membership “the lavender menace… threatening to warp the image of women’s rights.” Several prominent NOW members, led by lesbian writer Rita Mae Brown, resigned. The defectors wrote “The Woman-Identified Woman,” the first major discourse on lesbian-feminist thinking, which became the manifesto of the newly formed Radicalesbians.

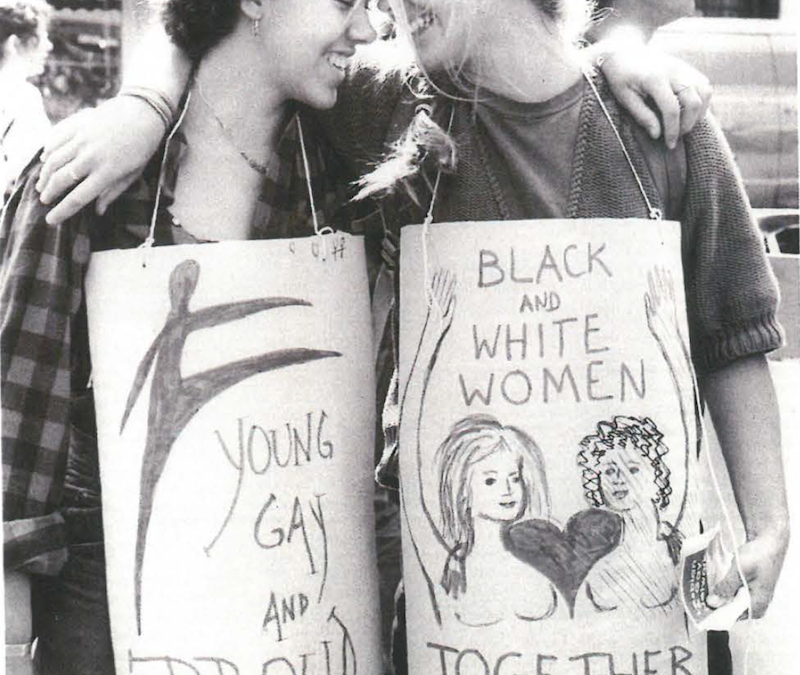

1970 Twenty-five members of Radicalesbians, dressed in lavender T-shirts emblazoned with the words LAVENDER MENACE, took over the Congress to Unite Women and demanded that lesbian issues be attended to.

1970 First Gay Pride March in New York, to commemorate the first anniversary of Stonewall.

1971 Founding of Gay Activist Alliance, about a third of whose members were women. Eventually, they broke away and formed the Lesbian Liberation Committee, which in turn became the Lesbian Feminist Liberation, which also absorbed the Daughters of Bilitis. LFL held weekly events at the Firehouse on Wooster Street, until the building was destroyed by arson in 1974. LFL survived as a strong voice in the lesbian community.

1972 Publication of Sappho Was a Right-On Woman, an account of the origins of lesbian feminism, written by Sidney Abbott and Barbara Love.

1973 Founding of the National Gay Task Force. Within a couple of years, NGTF had about 2,500 members and was fighting court cases on gay issues ranging from education to service in the armed forces. (In 1985 the NGTF became the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.)

1974 Founding of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, later incorporated as the Lesbian Herstory Educational Foundation, an institution dedicated to preserving lesbian cultural documents. The archive receives over 1,000 visitors a year.

1976 Founding of Salsa Soul Sisters, the country’s first organization for lesbians of color.

1983 The New York City Board of Estimate approved the sale of a city building to the gay community. A few months later, the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center opened at 208 West 13th Street.

1985 The Hetrick-Marrin Institute established the Harvey Milk High School, the first alternative high school for gay youth.

1986 Passage of Local Law 2, an amendment to the city’s human rights law. First introduced in 1971, the so-called gay rights bill was the only bill in the history of New York’s city council to have been passed in committee and fail on the council floor (in 1974). The amendment makes it illegal to discriminate in employment, housing and public accommodations because of sexual orientation.

1983–89 The Sharon Kowalski–Karen Thompson case focused public attention on the issue of domestic partnership. After Kowalski was severely disabled as the result of a car accident, her parents learned that Thompson was their daughter’s lover and obtained a court ruling that denied her visitation rights. Thompson’s long crusade to regain them ended in 1989, when a judge determined that Kowalski could make her own decisions about whom she wanted to see.

1989 In Braschi v. Stahl Associates, the New York Court of Appeals ruled in a landmark case that a gay man could be considered a family member of his deceased lover. The plaintiff, Miguel Braschi, was awarded the right to take over the lease on his lover’s rent-controlled apartment (where the couple had lived for ten years), a privilege formerly reserved for traditionally recognized family members.

1989 Executive Order 123 established the right for domestic partners who, among other criteria, “have a close and committed personal relationship, involving shared responsibilities” to register their partnership and thus qualify for certain work benefits.

1989 Massachusetts was the second state to pass an anti-gay discrimination law (Wisconsin passed the first in 1982).