“So he says—first question—‘Do you believe in sin?’

“Do I believe in sin? I mean, gimme a break.”

This is the sound of Pete Dexter dealing with fame.

It wasn’t so long ago that Dexter could limp over to 13th and Pine and climb on a bar stool in Dirty Frank’s and just sit, and quietly drink and watch things, staring over his big knuckles with a deep-set pair of eyes the color of dark-roast coffee beans. He was famous even then, but it wasn’t from the sitting and watching. It was from what happened later, once he was under the influence of several cocktails and an insatiable need to have fun.

Like peeing in police cars. Painting chickens blue and red to look like parrots. Picking up hitchhiking Mexican midgets at 4 in the morning. Most of the stories were actually true, but even that wouldn’t have advanced his reputation much beyond Frank’s if he didn’t write about it all in a three-day-a-week “street column” in the Daily News that former editor F. Gilman Spencer says was “as funny as anything I’ve seen in print.”

Readers responded to Dexter. Some still carry his columns around, brown and tattered, in their wallets. Some—like the Lesbians Against Housework—picketed the newspaper building after he wrote about them. And once a small group of readers who didn’t like what he wrote nearly killed Pete Dexter with baseball bats.

Pete Dexter got plenty of attention then, but it wasn’t from writers for hip downtown New York magazines who wanted the details on moral issues without so much as a little chitchat first. Dexter became a subject himself after he started writing “serious literature” (he still puts those words in quotes when he uses them), and especially after the serious literature establishment handed him the National Book Award in 1988 for his third novel, Paris Trout. But even that might not have attracted the hip and the downtown if Dexter hadn’t also become one of Hollywood’s busy screenwriters—one who, says director Lili Zanuck, “should be making a million dollars for a script soon.”

“So the interview sort of went downhill from there,” says Dexter, who is talking over the wind, sitting in the open passenger seat of his Miata, having figured a few minutes ago that a good way to deflect an interviewer’s tough questions about things venial is to let him drive your shiny red sports car. He is a nervous passenger. We’re twisting through a stand of tall pines on an empty two-lane road on Whidbey Island in Puget Sound in northwest Washington. It’s overcast more than you’d expect paradise to be.

Dexter came here early in 1990, as his career was really taking off. He brought his wife and teenage daughter and bought a sprawling contemporary ranch house with a view of Useless Bay and eagles in the trees, and since then he’s climbed the stairs to his loft office in the mornings and written a thrice-weekly newspaper column for the Sacramento Bee (where he went after leaving the Daily News in 1986) and screenplays for the likes of Barry Levinson and Richard and Lili Zanuck, including the script for Rush, the story of drug-addicted female undercover narcotics agents which stars Jennifer Jason Leigh and Jason Patric and opens next month.

And from this place he remembered and imagined Philadelphia, where he has set his new novel, published last month by Random House. Brotherly Love is a stark, brooding story of two South Philadelphia cousins raised as brothers in the corrupt and violent vortex of unions and the mob that is the chronicle of deaths foretold. Since it follows Dexter’s big prize, it is one of those “eagerly awaited” works of serious literature.

You’ve got to board the Mukilteo ferry to get to Whidbey Island, and Dexter says this tends to keep the riffraff out. Yet all summer the interviewers have been dropping by. “And this guy, the guy who wants to know about sin,” Dexter says, picking up his story, “brings a tape recorder that’s about the size of a washing machine. And I take him with me to my gym. And he’s interviewing me with this big tape recorder while I’m working out on the heavy bag. I’m punchin’ the damn thing and he’s asking me questions. You know, getting in close.

“And I didn’t mean to do it, I really didn’t,” Dexter says, looking sort of like he didn’t. “But I just caught the recorder with a punch, and the whole damn thing went flyin’ across the room and there were batteries everywhere. I was real embarrassed and everything, and I helped him get it back together.

“So he leaves. Then I get a call from the fact checker for the magazine. And she says, ‘O.K., your wife’s name is Diane,’ which is right but they had it spelled wrong. My wife spells it Dian. ‘And your daughter’s name is Casey.’ That was right.

“And then she says, ‘And you like to hurt people, right?’”

The only thing Pete Dexter is hurting today is himself. “Shhhhit,” he hisses after he twists and uncoils, watching a golf ball fly straight but not true. “Oh, Pete.” He surveys the damage. “Ah, hell, that ain’t so bad. I normally lose about six balls on this hole alone.” Dexter’s got two artificial hips. He carries around enough Teflon and stainless steel for a decent kitchen, and he hobbles back to the golf cart and folds himself into the driver’s seat. He has a sharp-boned face that looks drawn in the sun. You have to be alert to catch him smiling.

These are tense times for Dexter. His fourth novel is done, but he’s waiting for the reviews. “As much as you try to ignore it,” he admits, “you take it personally.” This is also what his wife maintains is one of three sunny days all year on Whidbey Island, and he sure doesn’t want to be sitting inside this afternoon talking about serious literature, even if it’s his own. A few weeks ago Dexter concluded there weren’t enough games in his life, so he joined a golf club. He took it up for the fun, but you’d never know from watching him play.

“You want a pain pill?” he asks, pulling out a pack of white tablets. “They’ll really change your outlook.”

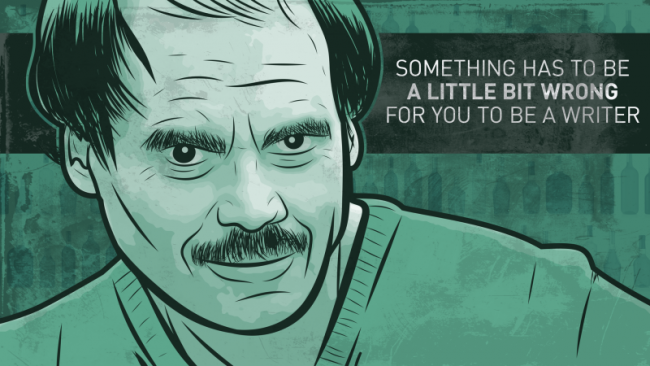

“I kind of buy that theory that something has to be a little bit wrong for you to be a writer,” Dexter says.

Pete Dexter is 48 now, and there are some who believe he’s been in constant pain for three decades, since he dislocated his hips playing high school football in South Dakota and never got them fixed right. If you read his fiction, you get the sense the pain’s been there longer than that.

“I kind of buy that theory that something has to be a little bit wrong for you to be a writer,” Dexter says. “Something has to have happened that gives you a different look at it. It just seems like there are a lot of people I know who are good writers who one way or another are damaged goods.”

The golf cart lurches forward. Dexter reaches to stow the pain pills. “You sure you don’t want one of these?” he asks again.

Dexter got damaged over time. His father died when he was two. His mother remarried, and the family grew and moved, from South Dakota to Georgia and back to Vermillion, South Dakota. His older sister, Kitty, says she and Pete never really knew their natural father’s profession: “It’s kind of crazy, an oddity, but I think it was my parents’ best effort to bring the new family together.” Dexter speaks of his stepfather with great fondness. When T.C. Tollefson was buried in Vermillion in 1978, Dexter wrote, “The sun was shining, and the cemetery windmill made slow, lost-calf noises under the preacher’s words.” Five years later, he dedicated his first novel to Tollefson.

In the midst of a family where the other kids (besides Kitty, he has two half brothers) breezed through prestigious colleges, Pete took his time getting out of the University of South Dakota. Then he migrated south, selling baby pictures door-to-door in New Orleans, working construction, pushing cars in Florida. He knew he could write, and finally an editor named Gregory Favre gave him a chance to prove it daily, at The Palm Beach Post.

“He was not the most productive reporter,” Favre remembers, “and that’s putting it kindly. But he wrote like an angel.”

He didn’t act like one. The stories that follow Dexter began there in Florida, where he started spending his spare time and a big chunk of his on-duty hours at the El Cid, a combination bar and barbershop. It seems only fair that an aspiring columnist, someone who wants to get paid to write about his life, would try to lead the most colorful one possible. Pete Dexter was more than fair. From all accounts, he believed in sin.

“I guess he just had to play out this male fantasy,” says one friend, Daily News columnist Dan Geringer, who worked with him in West Palm Beach. Gregory Favre soon quit the paper out of disgust, and Dexter did, too, out of loyalty. By 1973, Dexter (soon joined by Geringer) was pumping gas in Ron’s Belvedere Standard station in West Palm Beach, and it might have been the low point of his life. Dexter’s first marriage had ended. He was making about $2 an hour, and Geringer remembers that they used to peep into a nearby house at a woman dressing after her shower: “And we realized, no matter how old or ugly she was, we couldn’t even get her.”

“All the gas station stories have been told,” Dexter wrote later, “except the truest one, which is that it felt like we had used up all the luck we would ever have just getting those jobs. And there wasn’t anybody who wanted to give us a chance to be writers again.”

But Dexter had a little luck left. An editor at The Philadelphia Daily News, Dave Lawrence, did offer him that chance, and “I arrived three days later with one pair of boots, no coat, running as close to empty as I’ve ever been.”

Dexter glides the golf cart to a stop. He gets out to try a long putt, and I hold the flag for him. He’s played eight holes, and I can tell by now he doesn’t like to putt—partly because he misses a lot, but more because it’s such agony for him to bend over and get the ball out once it’s finally in the hole.

“I don’t really miss Philadelphia,” he says, surveying the green. “I do feel sort of nostalgic for it sometimes. And I miss some of those people a lot. But most of the people I cared about are gone.”

One is late Daily News columnist Larry Fields. “There’s a lot of stories about me,” Dexter says, “but compared to Fields, or even a guy like Jack McKinney, I’ve just done a lot of goofy stuff.”

Dexter was there the night in Atlantic City when a drunken Fields slipped $100 in Daily News money to a prostitute, thanking her but forgetting something: “I told him, ‘Larry, you’re supposed to fuck them first.’” Of Jack McKinney—with whom Dexter was known to toss 50-gallon drums in the alley outside the old Pen and Pencil Club—Dexter says simply, “He just did things that were majestic.”

Dexter’s warm and indulgent nostalgia stops at Clark DeLeon. He talks about the Inquirer columnist as if DeLeon is something warm he’s stepped in. And he’s even harder on Stu Bykofsky, who has inherited Fields’ job at the Daily News. “I guess he gets things into the paper,” Dexter says. “But personally, he’s just a slime.”

As he looked up from Dexter’s battered body, Randall Cobb delivered one of the all-time great barroom brawl lines to the men with bats: “If he’s dead,” said Cobb, “so are all of you.”

“Which way do you think this putt’ll break?” Dexter asks. I give him the wrong advice. “That’s close enough for me,” he says as the ball trickles a few inches left of the cup.

On the tenth hole Dexter mentions Randall Cobb, the former heavyweight boxer from Texas whom he wrote about, befriended and drank with while Cobb was training in Philadelphia. One night in late 1981, when he was still a contender, Cobb stood over Dexter’s crumpled frame on the sidewalk outside a bar at 24th and Lombard streets, in the neighborhood called Devil’s Pocket. Dexter had been beaten by a gang with baseball bats over a column he’d written about drugs in the neighborhood. As he looked up from Dexter’s battered body, Randall Cobb delivered one of the all-time great barroom brawl lines to the men with bats: “If he’s dead,” said Cobb, “so are all of you.”

Rather than dying, his friends think, Dexter was reborn that night. “It was his experience on the road to Damascus,” says Art Bourgeau, the owner of Philadelphia’s Whodunit bookstore, who’s an amateur boxer and professional mystery writer and the man who introduced Dexter to Cobb. “Similar to St. Paul being struck blind. He heeded the experience.”

“That’s bullshit,” says Dexter. “It was definitely the turning point in the evening. It was scary. But it wasn’t like I was scared straight or anything….I was kind of affected by how much it affected my wife, and by what it might have done to my daughter if I’d been killed.

“But it’s worth keeping in mind that the night this happened, I wasn’t drunk,” Dexter says. Still, when he got out of the hospital he quit drinking, because the blows to the head altered his taste buds, he says, and he couldn’t stomach alcohol anymore. A doctor told him that theory was all in his mind. “I didn’t miss drinking once I quit,” says Dexter. “I missed the bar stuff, the crazy stuff. But a lot of bar stuff is depressing. It’s not worth waiting for.”

When Pete Dexter decided to get down to work, he dug in and did it hard. He kept turning out his column and many magazine articles, and the energy that had gone into building his wild reputation now went fully into his writing. “In the beginning,” he says, “I’d write every single day. I wouldn’t miss a day. Christmas, I would write 900 words. I must have thought it was necessary. I have that compulsive thing in me. That’s why the game of golf is probably going to drive me crazy. If you read about some guy committing suicide with a sand wedge, it’ll probably be me.”

No one has yet called Dexter a natural golfer—and I won’t start a trend—but plenty of people call him a natural writer. “I’m largely unconscious when I write,” he says. “If I sat down to write and studied it—I mean, if I thought about it as much as I think about my golf swing—I’d probably be as bad a writer as I am a golfer.”

Dexter’s First Novel, God’s Pocket, was published in 1983, getting mostly decent reviews and a few good ones. It was a book about Philadelphia, full of the streets and bars that Dexter knew. The autobiographical elements were as thinly veiled as the title; a main character is beloved and besotted Philadelphia newspaper columnist Richard Shellburn. (“Tell me something about writing,” Shellburn is begged by a young woman in bed. “It’s like shaving,” he says. “You bleed worse than it hurts.”) The novel ends as Shellburn is killed outside a Philadelphia bar. “The book wasn’t a mistake, really,” Dexter says today. “Everybody’s gotta write a first novel.”

Random House gave him a $12,000 advance for his next book, a sprawling western set in Deadwood, South Dakota, a century ago, with characters like Wild Bill Hickok, his friend Charley Utter, and Calamity Jane. Deadwood came out in late ’85, and was called “unpredictable, hyperbolic and, page after page, uproarious” by a New York Times reviewer. The Atlantic writer, on the other hand, thought it was “never clear whether Mr. Dexter intended to write a novel about western frontier or a spoof of such novels.” Dexter thinks critics miss the point a lot, and he likes Deadwood best of anything he’s written so far.

“I think Charley Utter spoke with more authority for me than any other character I’ve created,” Dexter says. The real-life Utter was a hunter, fighter, lover, whorehouse operator and clean freak who was Wild Bill Hickok’s best friend: “[Hickok] never met a human being that didn’t already have an opinion on him,” Utter says to Hickok’s widow in the book, “and it was his nature to feel an obligation to fill their expectations. Myself, I can lie in the dirt talking to horses if I feel like it.”

“I’ve got an interest in violence. I’ve been around it. I’ve seen it, and I think I understand it. On one level it’s as simple as writing about what you know.”

Two years later, Paris Trout was published. It is a grim story of a psychotic small-town Southern shopkeeper who shoots a 14-year-old black girl over an unpaid debt and, after being convicted for the murder, shoots just about everybody else in town. The book is set in the 1950s, and the town of Cotton Point is much like Milledgeville, Georgia, where Dexter lived for five years as a young boy, at that age when memory and desire mix to form a person’s core. Milledgeville still feels like home to him, he says. Paris Trout is chilling, but also richly textured and leavened with good humor, with sentences in it that you don’t read so much as feel.

Dexter writes good sentences, and lays one after the other, like a straight brick wall. His writing has always been spare. “He never met an adjective he liked,” says Gil Spencer. But Brotherly Love is virtually devoid of ornamentation, leading some to criticize the style as repetitive. New York magazine said the prose in Brotherly Love is “impressive at first, but gradually makes you feel numb….” Critics miss the point a lot.

What little Dexter will say about writing is said in such concrete terms, as if it were possible just to get a union card and do it. “Writing isn’t something I talk about much,” he says. “I can. But, I mean, you’ve been in enough bars where there’s guys sittin’ around talking about being writers. Oh, man, it used to drive me crazy, that whole Clark DeLeon deal.”

The buzz at Random House was loud for Paris Trout. When the early sections arrived, there was talk that they were the best opening 100 pages anyone had seen in a long time. When the novel appeared, reviews were mixed. Robert Towers, in The New York Review of Books, praised the writing but wondered how we could care about a psychotic’s motivations. The Los Angeles Times’ Richard Eder, though, called Paris Trout “a masterpiece.” The book had slow but steady sales—until the judges gave it the National Book Award. (It beat out Anne Tyler’s Breathing Lessons and Don DiLillo’s Libra.) Then Pete Dexter became a best-selling author, one of those people that everyone has an opinion about. It’s not that he’s Hollywood famous. He could still lie in the dirt and talk to horses. But odds are that someone would quote him.

I mentioned Pete Dexter at a party recently, and a woman who’d never met him but who read and liked Paris Trout said, “There’s a lot of anger in that man.” Writers always run the risk of being confused with their books, but it’s true: There is more murder and mayhem on pages 294 and 295 of Paris Trout than on all of Whidbey Island in the last two decades. Brotherly Love is filled with brutality. And though it is described with less analytical precision, the violence in this latest novel is more frightening because it grows organically, its roots curled through the lives and circumstances of the South Philadelphians who populate the book. Even the hip interviewer with the big tape recorder got whiny about this part of Pete Dexter. “Why are your books so macho—?” he asked.

Dexter’s friends and family wonder where the violence in his books comes from, too, for they know him as a gentle man, a little crazy, but mostly shy when he’s not being funny.

“I’ve thought about the violence in his books a lot,” says his brother, Tom Tollefson, a Montana newspaperman who studied literature with Norman Maclean at the University of Chicago and introduced Dexter to Maclean’s masterpiece, A River Runs Through It, which Dexter reads once a year (along with Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man is Hard to Find”). “I don’t think there’s any simple or direct connection between Peter’s psychological makeup or life history and the things that happen in his stories,” Tollefson says.

Dexter isn’t sure of the connection himself. “I’ve got an interest in violence,” he tells me. “I’ve been around it. I’ve seen it, and I think I understand it. On one level it’s as simple as writing about what you know.

“I do know that in certain situations it’ll show character more clearly. Most of what you are will show over a long period of time—in how you treat your wife and your family and your brothers and your sisters and your friends. But there’s something else that you are, and sometimes a violent situation comes up, or a situation that has potential for violence, that in real life—I suppose in fiction, too—will crystallize part of you that people won’t see who have known you for ten years.”

In Brotherly Love, the crystallizing moments are everywhere. The story opens as Peter Flood is eight years old, and in little more than a blink he loses his sister, his mother and his father. His uncle moves his family into the Flood home and raises Peter, but the man who means the most to the boy is Nick DiMaggio, a neighborhood auto mechanic who runs a boxing gym. Dexter doesn’t even try to be coy about the inspiration for father-and-son characters Nick and Harry DiMaggio.

Dexter was taught to fight in the ring by Mickey Rosati, a warm and friendly South Philadelphia auto mechanic who also happens to be as tough as people get and who with his son, Little Mickey, teaches kids to box in a homemade gym above his garage. Randall Cobb introduced Dexter to Rosati not long before the fight in Devil’s Pocket. “If I had really known Pete then,” Rosati says, “that thing would never have happened.” Mickey Rosati thinks boxing improves a person—“It takes the chip off their shoulder.” In Dexter’s first days of sparring, Rosati remembers, the writer would apologize to his opponent every time he hit him hard. “Nah, Pete,” Rosati told him. “You don’t do that. It embarrasses them.”

“I wanted to write about Mickey and little Mickey,” Dexter says. “I wanted to get those people down on paper.” He gave the manuscript to Rosati before publication: “If there was anything in there that Mickey said would have embarrassed him or gotten him in trouble, I would have changed it in a minute.” Rosati didn’t change a word, and says he’s honored by the portrayal. He’s passed through Dexter’s word processor before. Once he got red-faced because Dexter wrote a Daily News column about the time he got hit by a car while jogging in the heart-print bikini underwear his wife, Marie, had given him as a joke. Later Dexter wrote a magazine piece about the night some punk showed up at the gym and tried to hurt Mickey Rosati in the ring. To Rosati it was another night of sparring, but Dexter had perceived the possibilities for heroism in the plain place above the garage. The fighter cried when he read it.

Rosati read Brotherly Love closely. “The Peter character,” Rosati says, “that’s Pete. No question about it.”

Dexter is not so ready to make that connection, though he admits, “I was a little less comfortable with the stuff going on in Brotherly Love. It was a little closer to the bone than the stuff in the other three books.” As the book ends, Peter Flood sacrifices a lot to protect Nick and Harry DiMaggio. “That friendship is something he’d put it on the line for,” Dexter says, “and it’s probably true in the end about how I think about things.”

It’s Whidbey’s fourth sunny day. Dexter is sitting in the ground-floor living room of his house, wearing pastel shorts and a T-shirt printed with a picture of Garfield and the word PHILADELPHIA. He’s still a little sweaty from punching the heavy bag in his health club, an activity I witnessed from a safe distance. As he talks, he slips his fingers in and out of a soda can.

“What I think is important to find out about Pete,” said one of his close friends’—who happens, like many of his friends who aren’t boxers, to be an editor—“is why he seems to keep moving further away from the world he writes about.” I’m trying to find out.

When Dexter decided to leave the Daily News in 1986, he was offered a columnist’s job by his old friend Gregory Favre, now executive editor of The Sacramento Bee. The readers of Sacramento had never seen the likes of Pete Dexter. He became a celebrity there, and it drove him crazy.

Then he started getting calls from a guy named Winston, collect, from prison. Dexter accepted them. It turned out that Winston had boxed a little in Texas, and good stories often come out of prison. But things just got weird.

“I wrote a column about the guy, without using his name,” Dexter says. “It was a funny column. Now, I didn’t think Winston could even read, let alone that someone would give him this column in prison. So he gets out in six months and comes back to Sacramento. And the first person he goes to is the sheriff, and he’s acting crazier than shit, and he tries to find out where I live.”

Dexter has seemed relaxed to this point, but suddenly that all changes: “That just pushed all the buttons for me. You start to pull my wife and my daughter into it, and now it’s serious. I started carrying a bat in a sack with me. That wasn’t because I had any question of how the fight would go if I met him. It was because I had every intention of killing him. Jesus, I would have killed the guy.”

Dexter demanded that the newspaper hire round-the-clock armed guards for his house. “I went from 160 pounds to 150. I couldn’t eat, couldn’t sleep. I’d call home 25 times a day. I get threatened a lot, always did. But this was different. People at work were afraid of me. At this point I was probably as crazy as Winston. It went on for six weeks, and it just took all my energy.

“It opened my eyes to a lot of things: Do I need it? Do I want it? I’d done a column at that point; I’d been writing them for 15 years. What are you trying to achieve? It still goes out with the garbage every single day. It doesn’t matter if you write Swann’s Way.” He was visiting Seattle to promote Paris Trout when he saw Whidbey. He moved there as soon as he could.

“It just changed everything for me,” Dexter says, relaxed again, sinking into the sofa. “I hardly have a temper at all now.”

It could be that Pete Dexter is happy at last. He seems settled in many ways: no more chip on his shoulder. Several times he has speculated on how his books will be remembered a hundred years from now. And he has bought what he thinks will be his last home, a stately pile on a bluff, protected by ten acres of pines and floppy ferns. “I would really like to have a couple of fuckin’ black cows in the yard,” Dexter said, showing me the new spread, “but Dian’s sort of put her foot down on that.”

“He seems a lot less angry now,” says a friend. “But why not? Everybody is being so nice to him lately.”

Some of those nice people are from Hollywood.

“That award made it a lot easier professionally for me,” Dexter says. “But obviously, it doesn’t make the books any better.”

After the National Book Award, Dexter began Brotherly Love with a $350,000 advance—four times what he’d gotten for what he calls Paris. That seemed like a lot of money. But Paris and its success attracted the movie people, the folks who, to paraphrase Frank Rizzo, pass around money as if it were lire.

“I sort of became obsessed with Pete Dexter,” says director and producer Lili Zanuck, who with her husband Richard produced Driving Miss Daisy. The couple argued over buying the rights to Paris Trout, which eventually was produced by Viacom for Showtime. Dexter was nominated for an Emmy Award for his screenplay and got to attend the awards ceremonies, which he remembers mostly because every time a beautiful woman approached him, he kept sticking his hand in the dessert.

“Lili really, really wanted it,” Dexter says of Paris Trout. “Dick really, really didn’t. They went at it for six months, and I don’t know what she did to him—or didn’t do for him—but finally he said, ‘Has the son of a bitch written anything else?’ ” The Zanucks bought rights to Deadwood, and Dexter wrote the adaptation. Then, when screenwriter Robert Towne pulled out of writing the adaptation of Kim Wozencraft’s first novel, Rush (the movie marks Lili Zanuck’s directorial debut), the Zanucks hired Dexter.

As Dexter finished Brotherly Love, the manuscript circulated in Hollywood. Dexter’s West Coast agent set the minimum opening bid—the floor bid—for the film rights at $1 million, with $500,000 extra for Dexter to write the screenplay. Fox bought it, to be developed by Barry Levinson (Diner, Rain Man), but the price dropped. “That was the floor,” Dexter admits, “but someone came in and punched holes in the floor, and we fell right through one.” Still, he stands to make a million dollars if the film is produced. “I’m not rich,” he says. “Not rich rich, not Beverly Hills rich.” His old newspaper buddies think he’s Beverly Hills rich.

“That award made it a lot easier professionally for me,” Dexter says. “But obviously, it doesn’t make the books any better. So the awards are nice, but they’re not….But I wanted to win that. If I had to pick an award to win—except for having the longest dick—that would be the one.”

There’s a story about Dexter going around L.A. that reached John Schulian, a former Daily News sports columnist who has become a television writer and producer. “Pete had finished a screenplay for Michael Mann,” Schulian reports. Mann, the producer of Miami Vice, is scheduled to direct a Zanuck production of a Dexter script about L.A. during the 1950s. “And Mann is telling Pete, ‘You know, Pete, this is a really good script. We really like it. But there seem to be an awful lot of gratuitous blowjobs.’ Dexter told him there’s no such thing.”

The phone rings. It’s his Los Angeles agent calling, reporting on the negotiations for an original film idea Dexter is developing with a friend, a Florida newspaperman. Dexter won’t say much about it, except that it’s funny and is about what would happen if one of those bizarre stories you read in the National Enquirer actually turned out to be true. Dexter starts talking Hollywood talk. “If we could get gross points,” he says into the receiver, “that would be great. I’d take that.” He hangs up just before “Ciao!” pops out of his mouth.

Even for someone with Dexter’s standards, Hollywood seems crazy. Still, his New York literary agent is worried that Dexter will be seduced by the town’s rich charms and stop writing books, just as “serious literature” has largely taken away one of our best newspaper columnists. Dexter slips back into the leather sofa, pulls his finger out of the Diet Coke can and considers.

“Nah,” he says. “L.A. is, in the real sense of the word, a scene. It’s fascinating to watch. The thought occurs to me that I would like to direct, but I would not want to live there.” Los Angeles, he says, “is full of people who have personal trainers and know eight kinds of karate and have never been in a fight.” That’s one way you’d expect Pete Dexter to measure things.

Just before Brotherly Love was published, as he was visiting New York on a round of publicity appearances, Dexter found out that the hip downtown magazine wasn’t going to publish its piece about him after all. The writer said he hadn’t been generous. Which means we may never learn whether Pete Dexter believes in sin. But he is as good as any evidence there is for redemption, lucky to be walking among us still, with a limp, slightly damaged goods.

[Illustration by Sam Woolley/GMG]