The year before Kobe’s troubles began, I had told him I thought he would love ballet because it’s as outrageously athletic and graceful and dynamic as he aspires to be. He went to see The Nutcracker and he did love it. Since then, he’s gone back to the ballet many times. He had always insisted—a little too fervently perhaps—that he wasn’t like other players. But whenever I saw him at the ballet, it struck me how different—in certain respects—he actually was.

Kobe is speaking. It’s late fall of 2001, a few weeks after 9/11. He has just finished a rigorous practice. He sits just off the court, uncharacteristically still, gazing past the rookies shooting free throws. He’s thought a lot about that September morning, a lot about the nature of disaster in general. “Things change in the blink of an eye,” he says. “It’s really scary. That’s the toughest part of life to me: People go to work and don’t come back. One minute they’re living; the next minute they’re not. And it doesn’t matter who you are. There’s nothing you can do about it. Bill Cosby’s son was killed. Something that still upsets me is the death of Michael Jordan’s father.”

Picture him in the cavernous room that used to be his bedroom, the grandest of six bedrooms in a mansion set high on a lush canyon top above the Pacific Palisades. This is the house he moved into in 1997, his rookie year. Back then he was a boy, not a man—an 18-year-old boy for whom there was nothing but basketball, dreaming of basketball and of possibilities as seemingly endless as the Pacific Ocean, which dominates the vista beyond his windows.

Picture him pacing the marble floors, pensive, sequestered, lost in the process of crafting words into poems. “It’s like a puzzle to me,” he would say. “I love mixing and matching the words.”

This room is his sanctuary. Like much in his life it is geared to accommodate his wishes, his needs, his cravings. What does he crave? Ask and odds are he’ll give you that irritated, incredulous look that says, you shouldn’t ask; I’m not telling. Still, his more material cravings are obvious: an outsize jacuzzi, fifty Armani sweaters in a customized closet.

Then, as now, Kobe is rich. He re-signs with the Lakers in 1999 for six years and $71 million. Some $12 million more for endorsing, among others, Sprite, Nike, McDonald’s, the chocolate-hazelnut spread Nutella.

Over seven years in the NBA Kobe gets some good-looking stuff: a black Mercedes coup, a black Ferrari, a white Bentley convertible, exquisitely tailored Zegna suits. Even so, in his bachelor years most of his wardrobe would look fine on a guy three times his age. It’s said that before he meets his wife Vanessa he doesn’t own a pair of jeans. “That’s not me,” he tells sales clerks in a tone that closes the subject.

That’s not me is a mantra of sorts, a cross to hold up to the vampire of impulse. What’s not me? Tattoos, for a start. He’s one of the few NBA stars who hasn’t got one. “What for?” he says.

For years Kobe keeps to himself, as if his teammates have a contagious disease he doesn’t want to be exposed to. He doesn’t accept their invitations to dinner even when the coach, Phil Jackson, tells him he should.

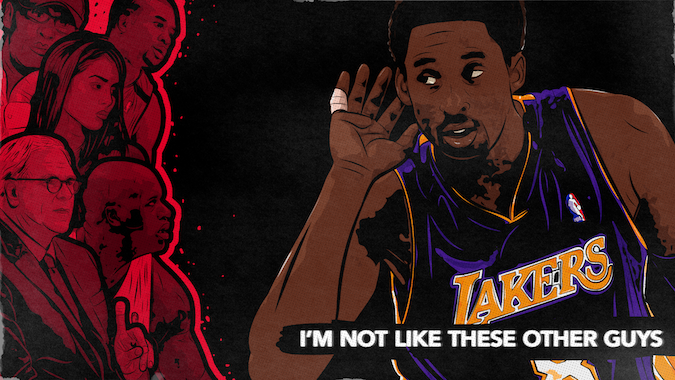

But he does have what you might call a credo. It’s short and to the point. I’m not like these other guys. But it’s more than a credo. Call it his Declaration of Independence.

These other guys. How can three affectless words reverberate with such contempt? What prompts this rush of feeling? Who are these other guys? His teammates suspect he means them. How many times have they wondered, “Does Kobe think he’s better than us?”

For years Kobe keeps to himself, as if his teammates have a contagious disease he doesn’t want to be exposed to. He doesn’t accept their invitations to dinner even when the coach, Phil Jackson, tells him he should. He doesn’t want to go to the mall with Derek Fisher, doesn’t show up when Jackson invites them all to a screening of Gladiator he’s arranged. On the team bus he sits at the very back, eyes glued to his laptop DVD player. On the plane he sits opposite the poker table, seemingly oblivious to the game, the joking, the laughter.

A rumor has been circulating since Kobe’s rookie year: that his father tells him to look out for himself, to not trust anybody on the team. In fact, the phrase these other guys is one that Kobe picks up from him. Kobe says his father taught him to love the game. Still, Joe Bryant’s feelings may be complicated, given that he played eight years in the NBA without attaining the reputation he felt he deserved. “Magic Johnson comes into the league with all that fancy stuff and they call it magic,” he says. “I’ve been doing it all these years and they call it schoolyard.”

These other guys looms as one of Kobe’s father’s legacies, perhaps the thing that most complicates his son’s life in the NBA. “These other guys on the team will be going out to clubs,” Joe tells a reporter at the start of Kobe’s rookie year. “Kobe will go back to his hotel and play Nintendo.”

What’s amazing is how readily Kobe obliges. Is he so absorbed in basketball that nothing else matters? Does he go along because it’s the least resistant path? Adolescent rebellion may be necessary to defining oneself, but it looks as though Kobe’s individuation process will have to wait. In the meantime his character will be filtered through the reporters who cover the Lakers, reporters for whom the first article of received wisdom is that the difference between Shaquille O’Neal and Kobe Bryant is that Shaq has never been an adult and Kobe has never been a child.

Picture Kobe in June 2003. Ask how he’s feeling. He says he feels great. But then, he always says he feels great. Weeks before his 25th birthday he’s got quite a résumé: seven-year NBA veteran, three NBA championships, youngest All-Star starter ever. Player whose No. 8 is one of the NBA’s best-selling replica jerseys.

In addition: product endorser. Citizen of Newport Beach. Husband. Father. Photographer of Natalia, his newborn daughter. No wonder he feels great.

In recent years there have even been some signs of healing. In January 2002 his high school jersey is retired at a ceremony in Philadelphia. He attends, flanked by people who previously would have had no interest in celebrating with him: a contingent of his teammates led by Shaquille O’Neal, Brian Shaw, and Rick Fox, and his mother and father.

Then everything changes. He opens the door to his hotel room. Try these for the résumé: adulterer, accused rapist. For the photo album, try a mug shot.

Some say they know that Kobe couldn’t possibly do what he’s accused of doing; others say they couldn’t possibly know Kobe. In the end two stories will be told in court by two people. One will be lying.

Let’s stick to facts. Kobe goes to Colorado to get his knees coped; he does this without consulting the team. The night before the surgery he’s relaxing at a mountaintop resort and orders room service. It’s delivered by a 19-year-old woman he met earlier in the lobby. Something happens in the room. The next day she files charges of sexual assault.

He denies the rape, admits the adultery. But let’s say for a moment that adultery is the sum of his malfeasance. It almost seems mild when you compare it with rape. Yet it would rock the foundations of his admirers, the faithful who log on to The Kobe Bryant Online Shrine. It’s curious that we assess wrongdoing on a sliding scale set according to the accused’s prior reputation. The more virtuous you are said to be, the more heinous your transgression seems. What’s shocking about Kobe’s infidelity isn’t the infidelity; it’s that the protagonist is Kobe Bryant, the infallible player who can do nothing worse, according to his fans’ mythology, than write bad poetry. You see why his admirers are grappling with what might be called an identity crisis—the identity at issue being Kobe’s.

Some say they know that Kobe couldn’t possibly do what he’s accused of doing; others say they couldn’t possibly know Kobe. In the end two stories will be told in court by two people. One will be lying.

What has taken place is one of those events that alter a life so radically that it becomes a marker dividing time into Before and After. In Kobe’s life this occurs three times: when he’s drafted into the NBA, when he meets his wife Vanessa, and when all hell breaks loose in Eagle, Colo.

Picture Kobe at age three, a miniature man in a miniature San Diego Clippers jersey, bright eyes fixed on the living room TV as he watches his father’s team. His father runs up and down the court; Kobe runs up and down the living room. His father shoots. Kobe tosses a tiny ball into a tiny hoop, collapsing in mock exhaustion.

He’s five when his father begins to teach him to play sports. He likes football and soccer, “but there was something about basketball,” he says now, “that I just loved so much.”

Are the most compelling activities the ones that rely on an individual’s strengths or are they the ones that also mesh with his weaknesses? Consider the way basketball meshes with Kobe’s temperament. “I had a real bad temper when I was a kid,” he recalls. “My mother told me to channel it into basketball.” He does. But while it gave his temper an outlet, the game reinforces his natural loner tendencies. “Maybe what I loved about basketball,” he says now, “is that you don’t need anyone else to do it. Other sports, you have to get a lot of people to come with you. The thing about basketball, you just pick up a ball and go dribble.”

Kobe is not quite six when he tells his father that he’s going to be an NBA player. His only concern is his lack of height. He’s in first grade and won’t hit his growth spurt until eighth grade. Looking around his classroom he wonders, “Is there anybody here I’m taller than?”

For a child he’s surprisingly serious. He’s quick, with an aptitude for shooting the ball. These things will determine his future. As his talent becomes more apparent, he assumes his place at the center of a family to which he is the hope for the future, the keeper of the flame, his father’s heir, his protégé, and, ultimately, his avenger.

In 1983 Joe Bryant’s NBA career comes to an end. But Joe is just 28, not yet done with the game. An offer comes from the Italian League, and he accepts. The Bryants will be the only black family in Rieti, Italy, where Kobe and his older sisters Shaya and Sharia arrive with no knowledge of Italian. Isolated by nationality, by color, they teach one another phrases, Kobe’s favorites, tira la bomba and bellisimo tiro, mean shoot the three and beautiful shot.

You can see Kobe’s life taking the shape it will retain from here on. Days are for basketball. He plays for hours by himself, alone against imagined defenders. He calls this shadow ball. For hours each day he plays, outwitting his own shadow. It will make him a great player, but not a great teammate.

Kobe’s grandparents send him videotapes of NBA games. Kobe is riveted by Magic, Michael, Larry Bird. He loves Magic’s passes, Michael’s dunks, Bird’s jumpers. “Okay,” he tells himself, “I’m going to combine those qualities.” Sitting in front of the television he studies the moves of each player. “I can do that,” he says aloud. “I can do that.”

Imagine being Kobe Bryant. Imagine being so bold and prodigious a dreamer that you picture yourself doing what others cannot even dream.

The Bryants return to Philadelphia and move into a house in Ardmore, an affluent suburb where substantial stone houses are shaded by centuries-old giant oaks. Kobe is 13. He’s back home but still an outsider. Hes peaks English with an Italian accent, can’t understand the slang spoken by kids his age. “I was focused on what I wanted to do, so I was pretty much separated from people my age,” he says. “A lot of them didn’t see the long picture.”

He’s at ease only when he’s playing basketball or when he’s deep in the fantasies in which he pictures himself on the court, an NBA player, spinning, dunking to cheers from the adoring crowd.

Picture him at 17, the USA Today High School Player of the Year. The 1996 NBA draft is just a few weeks away. Kobe announces at a press conference that he’s skipping college. “I’m taking my talents to the NBA,” he says. In the next day’s paper a writer speculates whether Kobe plans to accompany his talent.

He’s the 13th pick overall in a draft whose number one pick is Allen Iverson, who goes to the Philadelphia 76ers. Kobe is selected by the Charlotte Hornets but is traded the same day to the Lakers, as part of a masterplan to rebuild a fallen dynasty. Walking onto the court of the Forum, Magic’s court, is like the beginning of one of his dreams.

Imagine being Kobe Bryant. Imagine being so bold and prodigious a dreamer that you picture yourself doing what others cannot even dream. Imagine how it feels to discover that no matter what you dream, no matter how far-fetched or impossible the scenario, those dreams are within your grasp. Imagine how it feels to ride those dreams to the NBA when you’re 17. Imagine discovering that your dreams are not mere dreams. They are your future.

And yet. Some things don’t change. Kobe is an outsider everywhere, it seems. Even here he is separated by his gifts, his commitment, his seriousness. “Basketball’s a game, but it’s not a game.” he says. “It’s nothing funny.”

At practices certain things surprise him. “Things that were hard for other people were easy for me,” he says. “I saw that. And I saw my desire. I thought everybody had the same desire to maximize their potential. But mine was different.”

“Remember this,” Shaq tells Kobe, “See these people laughing at you? Just remember.”

“I hear the crowd’s cheers and I go wild,” he says. He wants to dunk, to pull off feats the fans have never imagined. To a veteran like Rick Fox, this says he’s undisciplined. “You get frustrated,” says Fox. “You wouldn’t give your 10-year-old the keys to drive the whole bus to school.” The coach at that time, Del Harris, doesn’t want to play Kobe for more than a few minutes. “Here’s this kid in a man’s game,” Harris says. “He should be on a team that isn’t expected to win right now.” But the crowd chants “Kobe,” and Harris sends him back into the game.

In Game 5 of the 1997 Western Conference semifinals, the score is tied in the last seconds of regulation. Harris puts Kobe in the game. Kobe gets the ball. It’s like one of his dreams: the key moment, with everything at stake, the crowd silent, expectant. He shoots. It’s an airball. In overtime he shoots three more airballs. When the buzzer sounds, no one thanks him for making sure that a tired team of players gets an early summer vacation. Head down, he walks off the court alone. Shaq puts an arm around him. He knows that failure can be the greatest motivator. “Remember this,” he tells Kobe, “See these people laughing at you? Just remember.”

In the seasons that follow, the coaches urge the other players to be patient with Kobe. After a time Shaq resents it. “When I came to this league I was supposed to be at 100 percent,” he tells a reporter. “No one said, ‘Be patient with Shaq. He’s learning.’”

Yet when it comes to basketball Kobe is better, perhaps, than anyone who ever played, with the inevitable exception of Michael Jordan. They all know it. They know that he knows it. “Putting Kobe in the NBA–what that’s like,” says his teammate Brian Shaw, “Is if you put me on a high school team. I could score whenever I wanted. I could get through four guys. I’d have to decide: Do I do that because I can do it, or do I play the right way?”

But Kobe is not always interested in playing the right way. By his fifth year that has taken its toll. He goes one night to the home of Jerry West, the Lakers’ general manager, one of the all-time greats and a man who understands that the exceptionally gifted play by a different rule book. “My teammates hate me,” Kobe tells West.

“I’d hate you too,” West responds, “if I were your teammate.”

Kobe’s ability to be objective about himself is his great strength. He knows what he needs to do. He distributes the ball. “You’ve changed, man,” Rick Fox tells him. “And you’re not just talking about it. You’re showing us.” One night Shaq brings the ball all the way up the court and then passes to Kobe. But Shaq hasn’t dribbled his way up court to watch Kobe make a basket. “I threw it to him,” Shaq says later, “because I knew he’d throw it back to me.”

Picture Kobe just four years ago. He’s on location filming a video. Nearby, a group of dancers is on a break. He looks and sees only one of them, the most gorgeous girl he has ever seen. “What’s your name?” he asks. “Vanessa,” she answers, her voice a languid growl. He’s struck by a thunderbolt. He’s hopelessly smitten. If it’s all about surfaces, hey, give the guy a break. He’s 20 years old.

As it happens, Vanessa Laine is 17. She’s a senior at Marina High School in Huntington Beach. As it happens, he’s still living with his parents, and he’s kind of a mama’s boy even if he is the one who paid for the house. He doesn’t date unless you count going to his high school prom with the pop star Brandy, and that seemed less a date than a photo op. He likes the comfort of homemade meals, of watching movies with his family on his parents’ bed.

But has he always suspected that cocoons are not built tolast forever. Does he fret about what will become of him? It seems so when you consider his thought when he falls for Vanessa: “I’ll never have to be lonely now.”

They are like two dare-devil kids, Kobe and Vanessa: bungee jumping, riding mopeds, parachuting out of airplanes. They go to Santa Monica’s Third Street Promenade, where they see movies, shop, and visit their favorite jewelry store, Rafinity. He buys her diamond earrings and a diamond necklace.

Before Vanessa his idea of jewelry was a plain watch and cufflinks. He was never one to go for the big jewelry favored in the NBA, where all that glitters is white gold and the jewelry is so outsize that one player trying to board an airplane wearing a six-inch cross is told to surrender it on the grounds that it could be a weapon.

For their first Christmas he gives her a little dog they name Gucci. She gives him a watch with a face edged in two rows of diamonds. One afternoon at the jewelry store Kobe agrees to have his ear pierced. Is he trying to make her happy? It won’t make his family happy, that’s for sure—they don’t approve of Vanessa as it is—and he’s not all that convinced he’s going to like it either. Just the year before a reporter asks if he will ever get an earring. “I don’t want to offend anybody,” he responds, “but it’s not for me.”

But he is perhaps more malleable than one might imagine. Especially in the French-manicured hands of Vanessa, who will do the piercing herself. The shop’s owner can’t believe what she’s seeing. Here’s Kobe Bryant, looking nervous, wondering if he’ll faint; Kobe, the fearless player, who storms through defenses of three, four, even five guys and thinks nothing of it. But can he handle this? When Vanessa pierces his earlobe, he doesn’t feel it. He doesn’t faint. A few weeks later he’s designing what he calls a Lakers earring: one three-carat yellow diamond edged in purple sapphires. “Well,” says his sister Sharia when she hears about the piercing, “I guess we ought to be happy that he didn’t get a nose ring.”

Vanessa graduates from high school. Kobe is her date for the senior prom. That summer she moves into Kobe’s house, and the other Bryants move to a smaller house a quarter-mile away. Life with Vanessa is making him more at ease, more sure of himself, more balanced. “I still love basketball,” he says, “but I’ve got another love now.”

Kobe has always planned to marry young. He’s 21 when he proposes. Vanessa is 18. She accepts. His family is not happy. He has to choose between them, choose between the woman he loves and the family that reminds him of the family in The Godfather. “Not in the violence,” he explains,“Because we all pull for each other no matter what.”

He chooses Vanessa. His parents move back to Philadelphia. In June the Lakers play one of his father’s former teams, the 76ers, in the NBA finals. Kobe leaves a pair of seats for his parents every night, but they don’t show up.

“I feel like one of those tigers in the zoo, where all the people stand around looking at you, trying to make you roar.”

Picture him the next season, 2001-2002, when it’s clear something isn’t right. He gets called for six technical fouls in the first month alone, more than his total in any previous season. He gets into a fistfight with his teammate Samaki Walker. He goes after Reggie Miller at the end of a game and gets a two-game suspension. “I want you to be aggressive,” Phil Jackson tells him, “not belligerent.” He’s swearing a lot, even in front of reporters, who write it all down.

Midseason, Sports Illustrated, not known for dedicating entire feature stories to changes in a player’s psyche, is moved to commission an article titled “What’s Up with Kobe?”

His teammates see what a thin rope he’s walking. Brian Shaw can see why: “All the pressure to win, to be better than you were, to lead the team but not take over the team, all the eyes on you at every minute.”

Kobe senses those eyes on him, too. “I feel like one of those tigers in the zoo,” he says, “where all the people stand around looking at you, trying to make you roar.”

Only when he’s playing does he seem set free. Playing loosens the bonds of the shyness, of the reticence he sets aside at times but never sheds. Playing is his escape from the everyday, with its deadening politeness, a way into an unfettered world that turns on focus, power, desire. There’s an inner dialogue in sports, and Kobe runs through his version of it before a game: No matter who you are, I’m coming after you.

“We have to beat people, dominate people. The only purposeis winning.” Sometimes he thinks these words. Sometimes he says them. It’s his will to win, his refusal to lose, that reminds Phil Jackson of Michael Jordan.“And that hasn’t happened very often,” says Jackson.

A great player’s game is a game with a subtext. The subtext of Kobe’s game reveals itself on the night some guys he knows from New York are sitting courtside. He’s known these guys a long time. They’re always talking trash, and now they’re dishing it out. Kobe takes the ball, powers through a triple team, and slams the ball through the hoop. He turns to them and spits out the words: “Don’t fuck with me.”

“It’s instinct. Killer instinct,” he says later. “You beat them. Then you crush them.”

But it may be that his most cherished times are long before tipoff, when he comes onto the court and plays the game he fashioned for himself as a kid, the game he named shadow ball and plays against his own shadow. As he blows past imaginary opponents, pushes through imaginary defenders to take the ball to the basket, a smile will start in his eyes, and minutes later he’s beaming.

“Man, it’s so much joy,” he’ll say.

Is any of this relevant to who he is when the game is over? Only if you believe that what a man is capable of doing on the court has a bearing on what he is capable of doing off it.

Picture him now, when what he is capable of has become a question to be answered by jurors. Days after he’s indicted he speaks his piece at a press conference before 200 or so reporters.

Head shaved, penitent, no stranger to shame, he’s the private man who compromised his right to privacy. Shorn of pride, swagger gone, he’s too self-disgusted to balk at being singled out as a sinner. Thus does the assemblage witness something previously unimaginable: a media event, on national television, that culminates in Kobe Bryant pleading for his wife’s forgiveness.

As tape whirrs in their hand-size recorders, is there not a man among them with a conscience strong enough to ease Kobe’s burden by saying, “Been there; done that?” It would be enlightening to know what’s on their minds—on the mind of anyone, in fact, who has paid enough attention to Kobe Bryant’s journey to be unsettled by the discovery that suddenly there’s pathos or irony in most everything he’s ever done: the 12 three-pointers in a half, the nine consecutive games in which he scored 40 or more points, the feats of will and daring that, once remembered, make this sad, solemn rite seem even more dissonant. There’s his recent remark that, of all the college courses he’s been taking, his favorite is criminal law. There’s the line from his commercial for one of the companies that has since backed away from him: “What’s my thirst? Staying on top.”

Picture Kobe in his bedroom. Does he wake these days with a start, pace the floor, wonder if all of it—the careful plans, the years of dedication, the love of being on the court—has been for nothing? Or maybe he wakes to a sense of peace, to the belief that it will all come out all right. Maybe he imagines himself playing shadow ball, feinting this way, that way, outfoxing his most worthy opponent: himself. Or does he recall how it feels to be in the zone, of how the basket seems to become huge and time slows, and he’s in a place like no other. Not long ago, he talked about being in the zone, about what made it a kind of religious experience. “You realize,” he says, “that you can do anything you want. And there’s no amount of work that can get you to that place, because what you’re feeling is faith in your skills. Belief. You become the game.”

He used to say, “No one can break me.” At times that phrase seemed the assertion of one who regards self-dramatization as the better part of valor. Now it’s different. Now there are intimations that he is, indeed, breaking. But then breaking may not be entirely a bad thing. Not if what they say is true: that you become strong in the broken places. Maybe he can wrest out of this something useful, something of value. Maybe when he wakes in the middle of the night the person he encounters will be himself. Does he know who that is? He thinks so, and it’s not at all who he thought he was when he saw himself as being so different and better than those other guys. “I’m just a man,” he says at the press conference. “I’m like everybody else.”

This story is collected in Kaye’s ebook anthology, Men: What They Do, How They Think, And Why.

[Illustration by Sam Woolley]