He was just another bum bleeding to death in an alleyway at four o’clock in the morning. He lay motionless on the concrete, as if sleeping, his tangled shoulder-length hair ringed by a halo of blood. He lay there peacefully for a while, in the darkened alley in a strip shopping mall in Wilton Manors, Florida, on the morning of September 12, 1987. He was less than an eighth of a mile from a police station and only a few feet from the Midnight Bottle Club, the Bread of Life health food store and a religious supply store with a sign in its window: “God Loves You.”

When the police arrived, a woman from the bar was kneeling beside him, wiping the blood out of his mouth so he would not drown in it. She looked up and said, “Jaco’s hurt.” One officer bent down and massaged the man’s shoulders while the other looked for witnesses. Only the bar’s bouncer came forward. Luc Havan, 25, a Vietnamese refugee, said that the man had tried to kick in the bar’s door after he had been denied entrance because he was drunk and abusive. When the bouncer chased the man down the alley, the man threw a glancing blow at him. The bouncer shoved him and he fell backward, hitting his head on the concrete. That’s all there was to it, the bouncer said.

The police report listed the cause of injury as a “blunt trauma to the head.” His skull was fractured. Bruises were everywhere. Both eyes were swollen shut. There was massive internal bleeding. Prior to the incident, he had been an “at-large person,” a vagrant with no known address or visible means of support. Over the past four years, “the victim” had been arrested in and around Fort Lauderdale many times for being drunk and disorderly; for resisting arrest during an argument with his second wife; for stealing patrons’ drinks and change at jazz clubs; for driving a stolen car around and around a running track; for breaking into an unoccupied apartment to sleep; and, finally, for riding naked on the hood of a pickup truck.

“So, you see,” said the investigating officer, “the victim was not unknown to us. Still, no one deserves to die like that. He was beat to hell. He died for no reason.”

John Francis Anthony “Jaco” Pastorius III lay comatose in the intensive-care unit of a Fort Lauderdale hospital for nine days, unrecognized until he was spotted by the doctor who had delivered his children. Once he had been identified, local newspapers ran photographs to accompany stories headlined “DARK DAYS FOR A JAZZ GENIUS” and “JAZZ PERFORMER’S LIFE STRIKES A TRAGIC CHORD” and “THE LONG, SAD SLIDE OF A GIFTED MUSIClAN.” The various photographs seemed to be of different men. One was of a man with narrowed, distrustful eyes, smirking lips and a wispy goatee like Ho Chi Minh’s. Another showed a man with lank shoulder-length hair and exhausted heavy-lidded eyes. Still another pictured a tense man, an animal ready to spring, with a fierce, manic look in his eyes, his hair pulled back almost painfully tight into a ponytail. And, finally, one photograph, the photograph published on the day he died, showed a sad, sweet-faced boy-man with a look of innocence in his haunted eyes.

Jaco Pastorius died on September 21, without ever regaining consciousness. He was 35 years old. On his deathbed, he was surrounded by his parents, his two younger brothers, his two ex-wives, his four children and his friends. Only his girlfriend of the last three years of his life was not permitted to be at his side. Although his loved ones cried at his death, they were not surprised by it. It came as almost a blessing after years of suffering, both his and theirs.

“No one deserves to die like that. He was beat to hell. He died for no reason.”

When she first heard the news, recalls Ingrid Pastorius, Jaco’s second wife and the woman he’d loved until he died, “I said to myself, ‘My God! Jaco finally got some sucker to do the job for him.’”

At his funeral, jazz musicians took turns playing the music he had composed. Eulogies poured in. Guitarist Pat Metheny called him “a legend.” Herbie Hancock called him “a phenomenon.” Hiram Bullock called him “a true genius on the level of Mozart.”

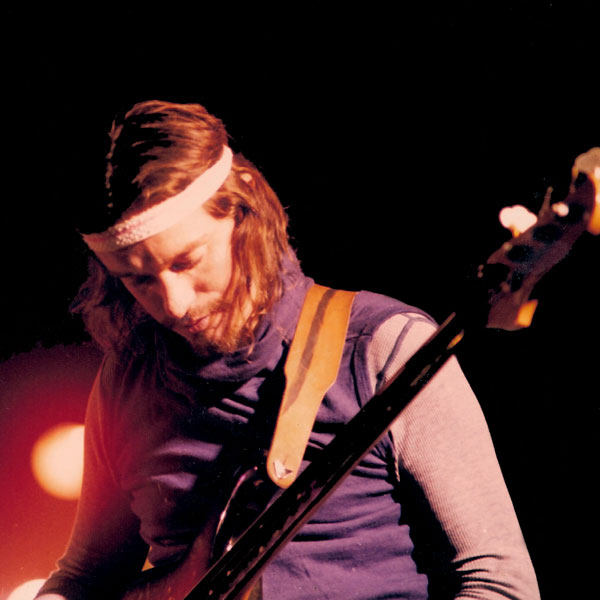

Jaco Pastorius, untutored and untrained, was the greatest bass-guitar player of all time. His innovations have influenced every bass player since and every form of contemporary music, from punk rock to Michael Jackson. He took an instrument long neglected melodically, that had always provided a thumping background rhythm from the shadows of a bandstand, and brought it into the spotlight. In Jaco’s hands, the electric bass became small and light, like a guitar. He played innovative melodies with an almost manic intensity. He once played a one-and-a-half-hour solo concert at the Newport Jazz Festival that hypnotized his audience, not only because of the originality of his music but because of the intensity with which he played and the pain he suffered to produce his music. He lay on the floor and played his bass above his head. He stood up and did flips off the instrument. He slammed his bass to the floor and walked offstage while the guitar reverberated with a sound that went beyond noise into music.

His rubbery features were contorted in seeming agony as his long double-jointed fingers fluttered up and down the strings with a speed and strength never before associated with such a tightly strung, thick-stringed instrument. The higher up the neck of the bass he played, the tighter the strings became and the more strength he needed to pour into his fingers, until they seemed about to snap backward and break. He played like this for hours, with a marathon runner’s obliviousness to pain. His fans worshiped him. They came early to his concerts and sat with their eyes closed, their knees pressed together, rocking in their seats as they chanted softly, “Jaco! Jaco’ Jaco!”

“We all had a lot of guilt over Jaco’s death,” says Ingrid Pastorius. “Guilt and denial. We didn’t know who to blame.”

“l heard him play only four bars and I knew history was being made,” says Joe Zawinul, cofounder of the jazz band Weather Report and the man who helped bring Pastorius his greatest fame. “Before Jaco, Weather Report was a cult band, mostly appreciated by blacks. Jaco was this nice white boy who brought us a new, white audience that made us much more commercially successful. Jaco was the greatest thing to happen to the band. And to me. He was my best friend.”

“Jaco was a monster,” says Peter Graves of the Peter Graves Orchestra. “He was a fully developed creative genius at 16. But…. Did you ever shoot those little wooden ducks in an arcade? There’s always a purple one, you know? Special. You see it, and then it’s gone, unless you shoot the sonofabitch.”

After Jaco’s funeral, after time had passed but their grief over his death still hadn’t subsided, his family and friends grew angry. “We all had a lot of guilt over Jaco’s death,” says Ingrid Pastorius. “Guilt and denial. We didn’t know who to blame.”

They blamed Luc Havan at first, but without passion. “I felt sorry for Luc,” says Jaco’s brother Gregory. “He was just the instrument of Jaco’s death.” Then they blamed Jaco’s childhood, his parents’ breakup, his father’s drinking. They blamed the genius that had evolved into manic-depression and the life-style he had led as a world-famous musician. The big cities that had lured him from his beloved hometown. His fans’ adulation, which he had both courted and feared. The drugs and alcohol he had been introduced to by older musicians he respected. Finally, they blamed one another, themselves even, and when none of this assuaged their anger, grief and guilt, they blamed the only person who had no defense against blame. His last girlfriend. A woman on the edge.

“She was the perfect girl for the role Jaco was in at the time,” says Ingrid. “Their relationship was based on craziness. They got drunk. They beat each other up.”

“I don’t know whether they were trying to save each other or destroy each other,” says Jaco’s good friend guitarist Randy Bernsen. “Maybe both.”

He was born on the first of December 1951 in Norristown, Pennsylvania, to a Finnish mother and a German-Irish father who could trace his ancestry back to one Francis Daniel Pastorius, who, in the year 1688, was among the first in America to call for the abolition of slavery. The name Pastorius comes from the Latin for “shepherd.” Jack and Stephanie Pastorius moved with their three sons, John, Gregory and Rory, to Fort Lauderdale in 1959 because both Gregory and Stephanie had asthma. Despite their father’s drinking and his long absences from home while he made his living as a jazz drummer, the boys led an idyllic life in what was then a sleepy southern town of palmetto trees, mangroves, avocado trees, inland canals and a spotless white-sand beach.

Because John and Gregory were separated by only two years, they were particularly close. They woke together at 3 A.M. to deliver newspapers on their bicycles, riding at breakneck speed through the darkened streets so they could finish on time to serve at morning Mass at Saint Clement’s Catholic Church, where they were altar boys. One morning, they were late for Mass, so they took a shortcut through the most dangerous part of town. Gregory was upended on his bike by a wire strung across the road. John pulled him into the bushes and hovered over him until they could escape at daylight.

“Jaco never slowed down,” says Greg. “He was always on the manic edge, always pushing fun to the limit. He took me to the beach during the worst hurricanes just to feel the power.”

By 11, John had assumed a protective role with his younger brother, partly because of their father’s long absences, and partly because Gregory was a shy, fat, sickly boy, in marked contrast to his older brother’s almost animal-like athleticism. Even then, John was a flamboyant youth who played sports with an intensity that was typical of skinny kids who make up in zeal what they lack in size and talent. From sports, he earned the nickname “Jocko,” for “jock,” which he would eventually change to the more exotic “Jaco” when he became a jazz musician.

“Jaco never slowed down,” says Greg. “He was always on the manic edge, always pushing fun to the limit. He took me to the beach during the worst hurricanes just to feel the power. It was a totally natural reaction to his environment. When he was 12, he was the best Little League baseball player in town. One day, a kid told me that my brother was an egomaniac because he was always saying he was the greatest. I didn’t know what ‘egomaniac’ meant, so I said, ‘But Jaco is the greatest.’ I worshiped him. He was the best brother any boy could ever have. When our dad would come home drunk, Jaco would say, ‘What a drag,’ and take me out of the house. We had a silent understanding even then that we would never drink, yet we both became alcoholics.”

Jaco, as the eldest son, was especially close to his father and so suffered most from his long absences. Often, Jaco would find a pair of his father’s drumsticks lying around the house, and despite his mother’s discouragement, he’d begin tapping them against the sofa, a chair, anything, in imitation of his father. On those rare occasions when Jack Pastorius had a gig near Fort Lauderdale, he often took his eldest son with him to the club. Jaco would watch while his father entertained the audience with his drums, a piano and a steady stream of humorous, hip patter. The audience repaid him by buying him round after round of drinks that Jack threw back, seemingly without effect.

When Jaco bought a set of drums, his mother refused to let him play them in the house. It was too much of a reminder of her absent husband and his life-style. “They fought like animals over his music,” says a friend, “so Jaco rented a room in a warehouse and played there.” To further make her point, Stephanie deliberately bought Gregory a guitar and encouraged him to play.

“I couldn’t play it,” says Greg. “Jaco had no interest in it either, except every once in a while when he’d pick it up and play it beautifully. It depressed me. So many things came easy to him. Music. Sports. He got straight A’s in school. He was voted the most talented boy in his class. But it was music that was natural to him. That’s why he did it. He said he heard music in everything. A baby crying. A car passing by. The wind in the palm trees. All of a sudden, he’d say to me, ‘Shhh!’ and he’d listen. I didn’t hear a thing.”

At 13, Jaco became the drummer for Las Olas Brass, a teenage jazz band. When he broke his wrist playing football, he switched to the bass guitar, and within a week he was playing the band’s entire repertoire. He told a friend that he had known the bass was his instrument the first time he touched its strings. His music even then was like nothing ever heard from a bass player. Because Jaco had listened to jazz on a cheap record player he had won in a Rice Krispies contest, he could never distinguish the background bass from the up-front instruments. So when he began playing the bass, he played it in imitation of those melodic instruments, rather than of the rhythmic bass. His sound was so unusual that the band became famous throughout south Florida, often playing clubs at which Jaco had to be snuck in through the back door because he was underage.

Throughout his teens, Jaco lived the kind of clean, mischievous, energetic life often associated with small-town boys of an earlier era. When a member of Las Olas Brass tried to get him to smoke pot, Jaco refused. “We used to laugh at guys who drank and did drugs,” says friend Peter Trias, who says his own mother was a heroin addict. “We swore we’d never be like our parents. Music was our medicine to cure how we were raised.”

The Jaco Pastorius who went north in the early Seventies to “show the world I’m the greatest” was no longer a short-haired, clean-looking kid. He looked like the kind of scrawny, stringy-haired street youths who spend their time sitting on ice chests in front of convenience stores.

In the summer, Jaco practiced his music furiously for hours on end. He would take his sheet music to a music store and, under the pretense of buying a keyboard, play his compositions in a sound booth to make sure that the music he had created in his head matched that produced by the instrument. In the afternoon, he’d meet his friends at the outdoor basketball courts on the beach, where they would play intense games for hours. After each game, they’d throw themselves into the ocean to cool off, and then go play again. Late in the afternoon, they’d lie in the sun, getting brown, and more than once, Jaco would suddenly burst into laughter. “Can you believe it!” he’d say.

At night, Jaco and his friends would cruise Fort Lauderdale in whatever car or truck they could borrow from a parent. They’d go to a state park, strip naked and race wildly, like young animals, through the woods. At midnight, still energized, they would drive to the outdoor basketball courts at Holiday Park for still more games. While they played, they could see the bums and the winos and the drug addicts setting up their meager belongings under the trees for their night’s sleep.

“I met Jaco at a club in ’69,” says Randy Bernsen. “This cat starts crowding me like I’m in his space, so I move. He follows. Finally, he says real soft, ‘Man, we got to play together.’ After that, it was music, sports and hit the beach. Jaco had this incredible healthy balance in his life. Still, he was always on the nerve, man. Magic! I only touched that nerve three times in my life. Jaco was on it all the time. He’d say, ‘Randy, I got this power in me.’ He was in awe of it.”

Jaco’s interest in girls did not surface until his last year of high school. When he met a pretty, strong-willed blonde named Tracy Lee, he immediately asked her to go steady. He seemed to breathe a sigh of relief when she agreed. “Jaco always liked to say he was the greatest,” says Greg, “but he really never thought he could do it alone. He never did live alone until the very end. He always needed a woman to take care of the details of life. When he met Tracy, it was like, ‘Whew’ Good! Now that that’s out of the way, I can concentrate on my music.’”

The Jaco Pastorius who went north in the early Seventies to “show the world I’m the greatest” was no longer a short-haired, clean-looking kid. He looked like the kind of scrawny, stringy-haired street youths who spend their time sitting on ice chests in front of convenience stores. He wore a knitted stocking cap, a T-shirt, baggy shorts and high-top Keds, the type of outfit he would later wear during concerts.

“He told me he was the greatest bass player in the world,” says Zawinul. “I told him to get the fuck outta my sight.”

In Philadelphia, he hooked up with Wayne Cochran’s C. C. Rider band and toured with them for eight months. When he returned home in 1973, he married Tracy, and they took a tiny apartment over a laundry in Hollywood, Florida. Jaco played with a number of local bands, building a reputation as an uncompromising musician who was impatient with other players who couldn’t keep pace with his genius. Tracy helped support them as a waitress at a club called Bachelors III. When Bobby Colomby, a drummer, producer and founding member of Blood, Sweat & Tears, appeared at the club looking for local acts to sign up, Tracy told him that he should audition her husband because “he’s the greatest bass player in the world.” The next afternoon, Jaco stood alone onstage in the deserted club and auditioned for Colomby. Colomby was stunned. He immediately signed Jaco to a contract with Epic and brought him to New York to record his first album, with Herbie Hancock. Jaco spent the next couple of years touring with various acts—BS&T; Charo; Joni Mitchell, with whom he was reported to have had an affair—while waiting for his album to appear. And though he still had not touched either liquor or drugs, the musician’s life of long absences from home was beginning to cause friction with Tracy.

When Weather Report passed through Fort Lauderdale in 1975, Jaco approached Joe Zawinul for a job. “He told me he was the greatest bass player in the world,” says Zawinul. “I told him to get the fuck outta my sight.” Zawinul, an Austrian immigrant, had a reputation for being a tough, bright, hard-drinking man who spent his spare time playing sports and reading philosophers such as Nietzsche and Schopenhauer. When Jaco appeared outside his hotel room the next day, with his head down and his hands folded in front of him, Zawinul was impressed by his persistence. He agreed to listen to a tape of Jaco’s music. “It floored me,” says Zawinul, “but we already had a great bass player, Alfonso Johnson. Jaco kept in touch with me, and when Alfonso left a few months later, I called Jaco and offered him the job.”

The rest is history. With Jaco as the band’s “Catalyst,” his nickname, Weather Report became a commercial success and the most famous jazz band in the world, “fusing” jazz, R&B, calypso and country music. Jaco’s first solo album came out to rave reviews and was nominated for two Grammys. Jaco toured with the band for almost seven years and during that time built a relationship with Zawinul that was more intense than any Jaco would ever have. Jaco looked upon Zawinul as a father; Zawinul called Jaco his twin brother, a reference to his own twin. who had died during childhood. They were inquisitive, passionate, athletic, boisterous!y macho men who both wanted to live life to its limits. With one difference. Zawinul, then in his early forties, was a mature man with an innate sense of life’s limits. Jaco, in his early twenties, was still a young man who thought life had no limits.

One night, before a gig, Zawinul was drinking vodka in the band’s dressing room, as he often did. He offered Jaco some. Jaco refused. Zawinul told him to loosen up a little. Jaco took his first drink that night, and then his second. “He got strange after two drinks,” says Zawinul. “He started throwing things. I knew right away l had made a mistake.”

Within a few months, Jaco was drinking heavily. When he returned to Fort Lauderdale as a world-famous musician for a vacation in 1977, he was not the same boy who had left. There was now an angry edge to his intensity. A bitterness. Now when he told his friends he was “Jaco the greatest!” it was no longer an innocent outburst of belief. It seemed more like an affront meant to diminish his friends.

At night, Jaco was seen in all the local clubs. A crowd would part for him as if he were a visiting potentate.

Jaco laughed at his friends behind their backs. He said that watching Bernsen play a guitar was “like watching a guy jerk off without ever coming.” He said that his hometown was full of “vultures” trying to capitalize on his fame. It was just a town of rednecks, racists and motherfuckers, he said, and then, in the next breath, he bragged that he was still just a home boy who needed the Fort Lauderdale ocean because it was his baptism. It was as if he felt estranged from the town of his innocence, and so he blamed the town for his own loss.

At night, Jaco was seen in all the local clubs. A crowd would part for him as if he were a visiting potentate. At one club, Jaco saw across the room a girl who mesmerized him. She was tall, dark and beautiful in an exotic way. She looked different, as he looked different. He saw in her his tintype, a woman who had all the qualities he needed. He saw in her the placid, maternal comfort he would need now that things had fallen apart with Tracy.

Ingrid Horn Müller was born in Sumatra to an Indonesian mother and a German father. She had lived most of her life in exotic places—Asia, the Middle East, the Caribbean—but she had never seen anyone so exotic-looking as Jaco Pastorius. She loved walking into clubs on Jaco’s arm as he loved being seen with her. He said they were a two-person parade.

Soon Jaco began to take Ingrid everywhere. He became obsessive about her presence. “l always had to be there for him,” she says. “Twenty-four hours a day for three years. After a show, I had to be waiting for him in the dressing room. He’d say, ‘Help me!’ As long as I was there, I could control him. Jaco saw in me a place to get away from what he knew he was getting into. He used me—our love—as just another kind of addictive behavior. I was a drug for him, I know that now.”

In 1978, Jaco was divorced from Tracy, who was raising their two children, a boy and a girl. He married Ingrid a year later in the ruins of a Mayan temple in Tikal, Guatemala. After the ceremony, they went up into the mountains to a small village. Jaco saw an Indian woman in a red shirt beautifully embroidered with brilliant flowers and birds. He said he wanted to buy it. The woman refused. Jaco persisted. They went back and forth—yes, no, yes, no—while a crowd formed. Finally, Jaco wore the woman down, and she sold him her shirt. The crowd cheered.

“Jaco always got what he wanted.” Ingrid says. “Almost always.”

A few nights later, Jaco and Ingrid were driving through the jungle in a Jeep when suddenly he leapt off and ran into the black silence. He could be heard thrashing about, as if looking for something. Suddenly the jungle exploded with the beating of an enormous drum. Animals woke. Birds sang in chorus. A panther growled. The entire jungle responded to the music Jaco was making by slapping his palms against the trunk of a giant tree.

In 1980, Ingrid went with Jaco on tour in Japan with Weather Report. One day, before a concert, they got into a fight, and Jaco went out and got drunk. That night he could barely play. Zawinul was furious and threatened to fire Jaco on the spot. But the next morning Jaco appeared at his door, head down, hands folded, and said, “I want to deeply apologize.” Zawinul forgave him. A few days later, in Osaka, Jaco was drunk by eleven o’clock in the morning. “I made up my mind I was going to fire him as soon as we got back to the States,” says Zawinul. But when the band returned, Zawinul didn’t fire Jaco. “I could never fire the boy.” he says. “Instead, I tried to keep him occupied all the time. By then, he was drinking heavily on the band’s bus. I tried to distract him with sports, pool, anything.”

One night, Zawinul walked into a restaurant just as Ingrid punched Jaco in the face and knocked him to the floor. Jaco got up with an embarrassed grin and walked out. On another night, when Jaco was sober and went for a vodka bottle, Ingrid grabbed it from him and poured its contents down the sink. They fought, and again Jaco went out and got drunk.

“His music began to slip. It was still perfect, but it wasn’t fresh. It was like a circus act. Jaco relied on tricks he had done before.”

Ingrid had another problem with Jaco, besides his drinking—his guilt over having left Tracy and their children, which he took out on Ingrid. This became his pattern: to make each woman in his life suffer for his guilt at having left the previous one.

“By 1980, Jaco was always angry and drunk,” says Zawinul. “He began to try to out-macho me. To outdrink me, like a competition. Sure, I drank and occasionally did a little blow, but I liked myself too much to hurt myself. Jaco did everything to indulgence. Then his music began to slip. It was still perfect, but it wasn’t fresh. It was like a circus act. Jaco relied on tricks he had done before.”

And Jaco began to doubt his gift for the first time. One night, he told Greg that his greatest fear was that he couldn’t repeat his early success. He was afraid he wasn’t a genius after all. “All I am is clever,” he said.

When Jaco finally left Weather Report in 1981 to form his own band, Word of Mouth, Zawinul breathed a sigh of relief. He would see Jaco, his “twin brother,” only a few times during the last six years of Jaco’s life. In 1982, Jaco again toured Japan. Ingrid, who was pregnant with twins, refused to go. Once he was in Japan, Jaco’s behavior became so bizarre that his band members feared for his safety. He walked offstage one night in the middle of a set. He shaved off all his hair and painted his face black. He threw his bass guitar into Hiroshima Bay.

“After that,” says Peter Graves, “no one ever got close to him again.”

Back home with his newborn twin sons, Jaco told Ingrid she had stopped loving him because of the babies. When she lay down with the boys, Jaco stood over her and pouted. “When’s my turn?” he said.

Jaco began to stay away from home for days at a time. He’d return drunk, with other drunks, and play his albums for them late into the night. Early one morning, the neighbors called the police. Jaco poked his finger in one officer’s fat gut and began to laugh. Before the cop could react, Jaco threw his arm over his shoulder and told the cop he was “beautiful.”

“Jaco was an actor,” says Ingrid. “He pushed people to their limits and then turned them around. By the time that cop left, he was Jaco’s friend for life.”

He wandered the streets drugged and dazed in torn, filthy clothes and unlaced sneakers, carrying a basketball under one arm and his bass guitar under the other. He found a broom and began sweeping the city’s streets.

It was a standard game for Jaco: He abused himself in the presence of those who cared about him and then implied his behavior was their fault. Finally, Ingrid had had enough. At first, she had feared for her husband’s safety, but then, like most mothers, she feared for her children. “He was like a bad child,” she says. “He would do anything to get my attention.” One day, he invited friends to their home and then entertained them by jumping off the roof to show that, like a cat, he had nine lives. “I just couldn’t keep up anymore,” Ingrid says. “Maybe it was my fault. Maybe I didn’t know enough.” She made Jaco leave their house.

Late in 1982, Jaco went on tour in Italy. He got drunk one day and fell off a hotel balcony and broke his arm. His friends back in Fort Lauderdale assumed someone had beaten him up because by then he was getting drunk regularly and provoking people to hit him. “He was doing penance,” says Greg, “for Tracy, Ingrid and the kids.” A few months later, Jaco was so drunk he had to be pulled off the stage at the Hollywood Bowl, where he was scheduled to perform at the Playboy Jazz Festival. The MC, Bill Cosby, apologized to the audience.

A few months after that, Jaco was living the life of a bum in New York City. He wandered the streets drugged and dazed in torn, filthy clothes and unlaced sneakers, carrying a basketball under one arm and his bass guitar under the other. He found a broom and began sweeping the city’s streets. He spit at people, ranted at them, pulled his pants down one night and exposed himself to a couple walking hand in hand. The man chased Jaco with a knife. One night, he put “war paint” on his face and ran down the streets like a madman. When people tried to talk to him, he would lie down in the street and curl up in a fetal position. Often, he spent his afternoons at the West 4th Street park in Greenwich Village, disturbing the basketball games being played there. He would jump into the action from the sidelines, steal the ball and race downcourt for an unobstructed fast break. Then he would call Ingrid from a nearby pay phone to tell her how great a basketball player he was. In the next breath, he would plead with her to take him back. He begged her to come to New York with the twins.

“I was torn,” she says. “I went up there without the twins, and when I saw how he was living, I had him committed to Bellevue.”

At Bellevue Hospital, Jaco Pastorius was told he was manic-depressive, confirming an earlier diagnosis. His doctor there, psychiatrist Kenneth Alper, told Ingrid that her husband’s illness was probably genetic and that it usually surfaced in males when the normal stresses of adult life became most intense, between the ages of 25 and 35. Jaco was 31. The illness was characterized by grandiose behavior alternating with extreme depression, each mood lasting for a week or more. There are seven symptoms of manic-depression, and Jaco exhibited them all. Feverish activity. Talkativeness. Flights of fancy. Inflated self-esteem. Decreased need for sleep. Diminished attention span. Excessive involvement in destructive activities such as drug-taking, drinking or attempting dangerous physical feats.

Alper says that though there is a link between the disease and creativity, the illness is neither a sign of creativity nor a cause of it; Van Gogh was a genius in spite of his illness, not because of it. “An artist must live in the real world from which he derives his art,” says Alper. “A manic-depressive lives an inward-looking life in which he is unable to distinguish fantasy from reality. The more Jaco lost touch with the real world, the more his art suffered, rather than the other way around.” In short, Alper says, Jaco’s art did not drive him mad, but his madness drove his art from him.

Jaco spent most of the summer of 1986 in the psychiatric ward of Bellevue Hospital.

Jaco’s disease was always with him, but as long as he lived the kind of routine-oriented life he did as a teenager, says Alper, it was more likely to be controlled, more an energy source that was channeled into constructive activities, such as sports and music. Once Jaco took his first drink, that energy source began going haywire. Even if Zawinul hadn’t offered him that drink, Jaco would probably have turned to alcohol on his own. Manic-depressives generally use alcohol or drugs as a form of self-medication to mute the demons in their heads. “Jaco was born with music in his head,” Ingrid says. “He heard music in everything. If he heard a fart. he said, ‘D flat.’ He said music just went through him, as if he was a conductor. He couldn’t stop it.”

“When Jaco had problems over his last years,” says Greg, “he used to scream at me to be quiet so he could hear the music. When it got too much for him, he clapped his hands over his ears.”

Earlier, Jaco had been prescribed the drug lithium, which had calmed him to an extent. But it had side effects. It made Jaco impotent, for one. It also took the edge off his creativity, he said—terrifying to a man who felt he always had to be on the manic edge to produce genius. Jaco would have to take lithium for the rest of his life, which meant he would no longer be “Jaco the greatest!” He might have been able to live with that, and the impotence too, but the man who dazzled audiences for hours with his manual dexterity could never live with the drug’s third side effect.

“Lithium causes tremors of the hands,” says Alper.

Alper prescribed the drug Tegretol, which has fewer side effects, and Jaco tried to take it for as long as he could after leaving Bellevue. But it caused numbness in his hands. He would take it only sporadically until the end.

Terry Nagell met Jaco in New York City in 1984. She was 25, of Japanese-German ancestry, tall dark and beautiful in the same exotic way as Ingrid. A tense, nervous, excruciatingly thin girl who seemed constantly about to disintegrate before one’s eyes, Terry used drugs and was a self-described “mean drunk.” The relationship she formed with Jaco was based on a mutual desire to stagger to the brink of destruction without falling off. They kept themselves from that brink by abusing each other for three years. Terry abused Jaco because he was weaker than she and it gave her strength. Jaco abused Terry because she was the perfect scapegoat for the anger he could not unleash on Ingrid, who had betrayed him by not going to Japan with him years before.

Jaco spent most of the summer of 1986 in the psychiatric ward of Bellevue Hospital. When he was released, calmed by medication again, he told Terry that he was going home to Florida to see his kids, to get his Florida sound back and “to patch things up with Ingrid,” from whom he’d been divorced in 1985. And then, perversely, he asked Terry to go with him.

They lived with Jaco’s mother while Terry supported them as a waitress in a life she calls “normal, relatively.” “Jaco was removed from the craziness we had heard about in New York and Japan,” says Randy Bernsen. “He was cleaned up. We played basketball and had a few gigs. I told my record guy Jaco was clean. He said to call him in a few months if Jaco was still clean. We all thought Jaco was back. There was still magic in his music, though now he doubted himself, like us. ‘Even if I can’t play,’ he’d say. ‘I can still write.’”

He was daily tormenting his friends and loved ones, almost as if to see how much they would take. He’d break into their homes to take musical instruments or albums or, on one occasion, a wedding ring…

But all too quickly, the destructive behavior returned. At his mother’s birthday party in February 1987, Jaco and Terry got into a violent argument. Jaco stormed out and went on a drinking binge that lasted virtually until the day he died, seven months later.

Jaco spent those last months wandering the streets of Fort Lauderdale, just as he had wandered the streets of New York, with his basketball under one arm and his bass guitar under the other. He’d stop in at whatever bar he had not been banned from and cadge drinks by telling customers he was the world’s greatest bass-guitar player. “No one believed it,” says one bartender, “until one night he brought in all his albums.”

Jaco had stolen those albums from a friend’s house. By then, he was daily tormenting his friends and loved ones, almost as if to see how much they would take. He’d break into their homes to take musical instruments or albums or, on one occasion, a wedding ring, which he had given to Ingrid as a sign they would get married again. Often, he would show up at the clubs at which his friends were appearing. He’d wander around, spitting at customers, cursing them, stealing their drinks, and then would try to climb onstage to play with his pals.

Whenever he was arrested for one of the many insane offenses of his last months, he would call his friends collect from jail and ask them to bail him out. One night, he called instrument maker Kevin Kaufman thirty times, collect, before Kaufman finally refused to pick up the phone. Another time, he called Peter Graves collect and kept him on the phone for thirty minutes while he played his bass for him, Finally, one night Jaco was awakened by falling rain while he slept on railroad tracks.

“I asked him if he had a death wish,” Kaufman says. “He said, ‘No. Don’t be stupid.’”

Often, Jaco would appear, ragged, filthy and bruised, at the Musician’s Exchange jazz club and ask to play the piano. When someone finally recognized him, “he’d play these beautiful pieces,” says a friend, “and then he’d disappear into the streets.” Jaco slept at night in Holiday Park with the other bums. They would build a fire late at night and pass around a bottle of cheap wine while Jaco played for them on his bass.

Sometimes Ingrid would stop by with the twins. “In a strange way,” she says, “Jaco was at peace. I always thought he was just going through a stage and that one day he’d be out the other side and I’d be waiting for him. I still loved him, and I raised our sons with the idea that Daddy Jaco would come back to us one day. At times he was incredibly lucid. He was still working on his music. He worked on record deals from jail. He got a verbal contract from a CBS guy, and another record guy put up $5,000 bail for him once. People still wanted him to play. Someone called his mother from Italy to offer Jaco $20,000 a week, but she told them her son couldn’t do it.”

By then, Jaco had so devastated his mother that she could not even bear to hear about his life. When Ingrid and some friends pleaded with her to help get Jaco into a special treatment facility Ingrid had found, she refused to discuss it. (Stephanie Pastorius declined to be interviewed for this article.)

A few days before he tried to kick in the door of the Midnight Bottle Club, Jaco was arrested again. He had been badly beaten by someone he had pushed too far, and was filthy and raving that nobody loved him but God. He told one of the policemen that the next time he was going to get one of the cops to kill him because, as a Catholic, he couldn’t commit suicide. (The cop spread the word to other cops to be careful when confronting Jaco on the streets.) When Jaco sobered up, he called his brother Greg and harassed him until Greg agreed to bail him out. “I told him I didn’t want to see him again until he changed his life,” Greg says. “Those were the last words I ever spoke to him.”

On the last day of his life, Jaco Pastorius woke up sober. On a whim, he called Terry, whom he hadn’t seen in a few months. He asked her to meet him for lunch at the Bangkok Inn, a Thai restaurant. She did. He had cleaned himself up, and their lunch was going along fine until Terry asked if he could get her and her new boyfriend tickets to that night’s Santana concert at the Sunrise Music Theater. Jaco said he thought he could work something out. When Terry and her boyfriend got to the theater, they found two tickets for excellent seats. They also found Jaco, drunker than Terry had ever seen him. He gave Terry the finger and swore at her, then staggered inside. During the concert, Jaco leapt onstage and stood behind the band’s bass player, who, ironically, was Alfonso Johnson, the man Jaco had replaced in Weather Report almost thirteen years previously. Before the audience even noticed what was happening, Jaco was led off the stage by the theater’s security guards. As he was taken out, he said to Terry. “I hope you and your blond-haired boyfriend are happy together.” He paused, then added, “I’m dead.”

Later, at one-thirty in the morning, Jaco called Terry’s apartment, even drunker than he had been. He called her a bitch and then hung up. For the next two and a half hours, Jaco Pastorius was an “at-large” person, until he tried to kick in the door of the Midnight Bottle Club and he became a “victim.”

The day after Jaco was found beaten senseless, Terry went down to the club to confront Luc Havan, to see for herself what kind of person could allegedly do such a thing. She found a bewildered, soft-faced man who could only say “I’m sorry,” without looking her in the eyes.

She went back to her apartment and rummaged through some of Jaco’s old letters to her. Then she played a tape she had made of a Christmas night in Germany when Jaco had come home drunk and abused her. His voice was slow, deep, throaty, the voice not of an uncomprehending drunk but of an actor playing a drunk. He accused Terry of being unfaithful. He spit at her. He told her she was the cause of his separation from his two ex-wives and his four children. When he hit her, she screamed. He said it was all her fault because she didn’t love him. Terry fled from the room. While she was gone, Jaco called Joe Zawinul in Los Angeles and began to cry over the phone. He told Zawinul how much he missed him, and then he hung up.

“That’s the way Jaco was,” says Terry. “He pushed people, and then he tried to turn them around so that they would feel guilty and sorry for him. After I broke up with him the last time, I saw him one day with nail polish all over his face. He wanted me to think it was blood. Jaco let himself get beat up and put in jail so we’d all feel guilty. He used his drinking as an excuse to let things happen to him. He used me as an excuse, too. Jaco used everybody. He used them and pushed their buttons and then tried to turn them around. But he couldn’t turn Luc around.”

After Jaco died, Kevin Kaufman went to Holiday Park to see if his bass was still there. Once, when Jaco was in jail, Kevin had retrieved the bass from Jaco’s bum friends, who had hidden it for him. This time, however. Kevin couldn’t find it.

At Jaco’s funeral, Ingrid wore the red shirt Jaco had bought on their honeymoon. Terry did not attend.

On December 2. 1987, Luc Havan was formally charged with second-degree murder in the death of John Francis Anthony “Jaco” Pastorius Ill, who, in fact, had finally turned him around.

[Photo Credit: Pino alpino via Wikimedia Commons]