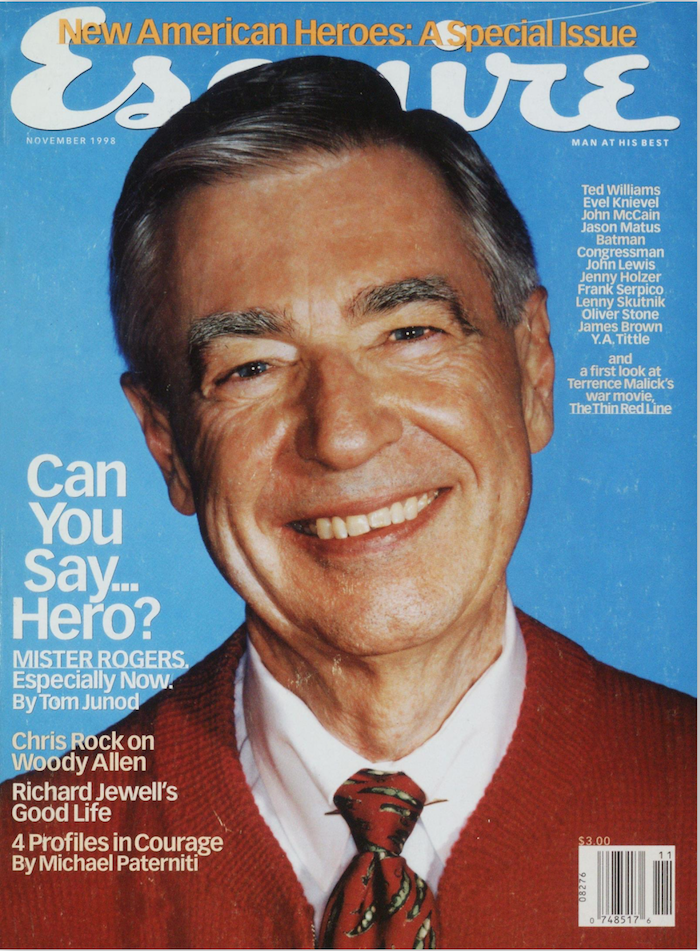

I’d heard nothing but good things about Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, Morgan Neville’s new documentary about Fred Rogers. Plus, our pal Tom Junod is a featured talking head in the movie and I was excited for him to be a part of it. Tom, if you don’t know, once wrote a wonderful profile of Rogers for Esquire. It was a cover story and the issues tanked on the newsstand but Tom got the last laugh—20 years later—as Tom Hanks is currently filming a movie adaptation of Tom’s friendship with Rogers.

Then I read this generous and smart Facebook post from another friend, Peter Richmond, who is one of the most thoughtful people I know:

A while back, in magazine land, there was a sort of golden age of feature writing that anyone within shouting distance wanted to be part of, a sort-of vague tournament of heavies … sort of like back in the sixties and seventies in boxing when even if you were just Earnie Shavers or Buster Mathis or Jimmy Ellis, and not Frazier or Ali or, later, Holmes, then Tyson, you were still in a position to earn some cred. It was tons of fun to try and be in the tournament. The usual way to get a seeding was to write dramatically about dark things that would get your piece anthologized: Killer bullets, murders, murders involving killer bullets, murders involving bullets and athletes, psychopaths, sociopaths, sociopathic athletes, warehouse fires, plane crashes, a chronicle of the usual members of the march of human despair.

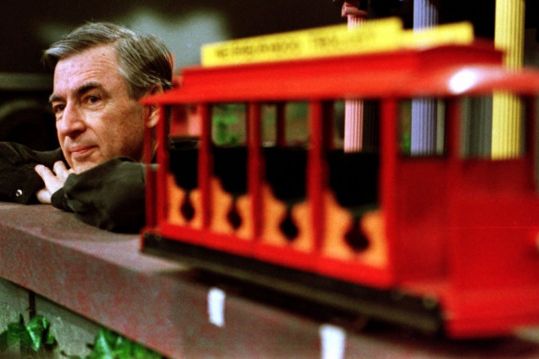

And it’s not that Tom Junod ever shied away from the grislysensational; I mean, when Bobbitt cut off her husband’s dick, it was Tom who went there, so. But it was also often Junod who had the talent of seeing around the bend when the rest of us only saw what was right ahead of us, and not just so he could be ahead of the storyteller game, but because, as a player in the human game, he was endlessly curious about everything. So when he came out with an extraordinary and extraordinarily good-hearted (and, as always, compelling) profile of Mr. Rogers for Esquire in 1998, it wasn’t unexpected, said the rest of us, but it was … counterintuitive. But then, that was Tom. And that’s all by way of saying that Tom’s piece directly led to Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, a movie that might be the most important documentary of my adult lifetime.

Yeah, I’m biased. I’m an extra-big believer in everything Fred Rogers believed in about the developmental stage of childhood (“Every child longs to be loved, and longs to know that they’re lovable”) (“What is essential in life is invisible to the eye”)(“Children’s outsides have changed; their insides haven’t”) and on and on … (it’s hard to take good notes in the dark) and about adulthood’s perverted ways of perverting that childhood, to try and crush it into what we think it should be. If you have children, want to have them, used to have them, well, if you don’t see this movie you … should. Tom is only one of the many wonderful talking heads here, but, trust me—you’ve gotten this far, why shouldn’t you?—this profound, and philosophic, and weepy, and religious (in the right way) and thought-provoking example of this medium is a direct—not indirect result of Tom’s vision and decision to write his story twenty years ago.

Did he write the piece because he sensed the beginnings of the possibility of the calamity into which we’d descend two decades later? I have no idea. But this movie would not have happened if an award-winning guy whose stories were, in retrospect, always about examining the way we are drawn toward what we are drawn—nothing more, everything more—hadn’t said in that one story: There is a beacon of human kindness, and I think I should tell you about him. Thank you, Tom. Thank you, filmmakers. Thank you Mr. Rogers.

I went to see the movie at a late morning screening with the old PBS tote bag crowd on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. As the movie was about to start a woman sitting a few rows down passed tissues to the friend next to her and the woman seated to my right placed a couple of tissues on her lap. I don’t know why, but a willful part of me was privately resolute not to cry at Mr. Rogers just because everyone around me seemed to be preparing for the waterworks. I never even liked Mr. Rogers when I was a kid. His mellowness unnerved me. I liked the louder and more antic comedy of Sesame Street and The Electric Company.

Yeah, well, no such luck. The tears, when they arrived, came freely. But whether you cry or not, I am sure you will get something out of the movie if you have not seen it already.