“A week never passes that the Alumni Office fails to receive news highlighting the good works of former football players. So many of them reflect credit on our University.”

—University of Tennessee Football Guide, 1970

What is fame?

An empty bubble;

Gold? A transient,

Shining trouble.

—James Grainger, 1721–1766

The evening began with an expedition to the friendly neighborhood liquor store four blocks away, where a purchase of four quarts of sticky-sweet Wild Irish Rose red wine was negotiated with a reedy gray-haired man behind the cash register. When the man saw who was shuffling through the front door his jaw tightened and he glanced nervously around, as if checking to be sure everything was nailed down.

“When you start drinking that stuff, Bob?” he asked.

“Since the last time I woke up and didn’t know what month it was,” said Robert Lee Suffridge, inspiring a doleful exchange about his drinking exploits. It was concluded that cheap wine at least puts you to sleep before you have a chance to do something crazy. Paying for the $1.39-a-quart bottles he trudged back out the door into the dry late-afternoon July heat and nursed the bleached twelve-year-old Mercury back to his apartment.

It is an old folks’ home, actually, a pair of matching six-story towers on the outskirts of Knoxville, Tennessee. At fifty-five he isn’t ready for an old folks’ home yet, but a brother who works for the state arranged for him to move in. Most of the other residents are well past the age of sixty-five, and to the older ladies like Bertha Colquitt, who lives in the apartment next to his and lets him use her telephone, he is their mischievous son. More than once they have had to call an ambulance for him when he was either drunk or having heart pains, but they don’t seem to mind. “Honey, if I was about ten years younger you’d have to watch your step around me,” he will say to one of them, setting off embarrassed giggles. God knows where he found four portable charcoal grills, but he keeps them in the dayroom downstairs and throws wiener roasts from time to time. He grows his own tomatoes beside his building, in a fiberglass crate filled with loam and human excrement taken from a buddy’s septic tank.

Getting off the elevator at the fourth floor, he thumped across the antiseptic hallway. The cooking odors of cabbage and meatloaf and carrots drifted through doorways. Joking with an old woman walking down the hall with a cane, he shifted the sack of wine bottles to his left arm and opened the door to his efficiency apartment. A copy of AA Today, an Alcoholics Anonymous publication, rested atop the bureau.

A powder-blue blazer with a patch reading “All-Time All-American” hung in a clear plastic bag from the closet doorknob. The bed, “my grandmother’s old bed,” had not been made in some time. Littering the living room floor were old sports pages and letters and newspaper clippings.

“Not a bad place,” he said, filling a yellow plastic tumbler with wine and plopping down in the green Naugahyde sofa next to the wall.

“Especially for forty-two-fifty a month.”

“What’s your income now?”

“About two hundred a month. Social Security, Navy pension.”

“You don’t need much, anyway, I guess.”

Fame is an empty bubble, indeed, easily burst if not handled with care. What happens when the legs go, the arm tires, the eyes fade, the lungs sag?

He stood up and stepped to the picture window that looks out over the grassy courtyard separating the two buildings. In the harsh light he looked like the old actor Wallace Beery, with puffy broken face and watery eyes and rubbery lips, his shirttail hanging out over a bulging belly. “I’m an alcoholic,” he said in a hoarse whisper. “I’ve done everything. Liquor, pills, everything. I don’t even like the stuff. Never did like it, not even when I was playing ball. Hell, only reason I used to carry cigarettes was because my date might want a smoke.” He drained the wine from the tumbler and turned away from the window, and there was no self-pity in his gravelly voice. “I came into the world a poor boy,” he said, “and I guess I’m still a poor boy.”

The 1970 Tennessee Football Guide was generally correct, of course, when it boasted about the steady flood of “news highlighting the good works of former football players.” The good life awaits the young man who becomes a college football star. He gets an education, or at least a degree, whether he works at it or not. He becomes known and admired. He discovers the relationship between discipline and success. He makes connections with alumni in high places—men who, in their enthusiasm for football, cross his palm with money and create jobs for him. About all he has to do is mind his manners, do what he is told, and he will be presented with a magical key to an easy life after he is finished playing games. The rule applies to most sports. “If it hadn’t been for baseball,” a pint-sized minor-league outfielder named Ernie Oravetz once told me, “I’d be just like my old man today: blind and crippled from working in the mines up in Pennsylvania.” For thousands of kids, particularly poor kids in the South, where football is a way of life, athletics has been a road out. Look at Jim Thorpe, the Native American. Look at Babe Ruth, the orphan. Look at Willie Mays, the black man. Look at Joe Namath.

But look, also, at the ones who couldn’t make it beyond the last hurrah. Look at Carl Furillo and Joe Louis and the others—the ones who died young, the ones who blew their money, the ones who ruined their bodies, the ones who somehow missed the brass ring. Fame is an empty bubble, indeed, easily burst if not handled with care. What happens when the legs go, the arm tires, the eyes fade, the lungs sag?

Some cope, some don’t. The reasons some don’t are so varied and sometimes so subtle they require the attention of sociologists. But the failures are there, and they will always be with us.

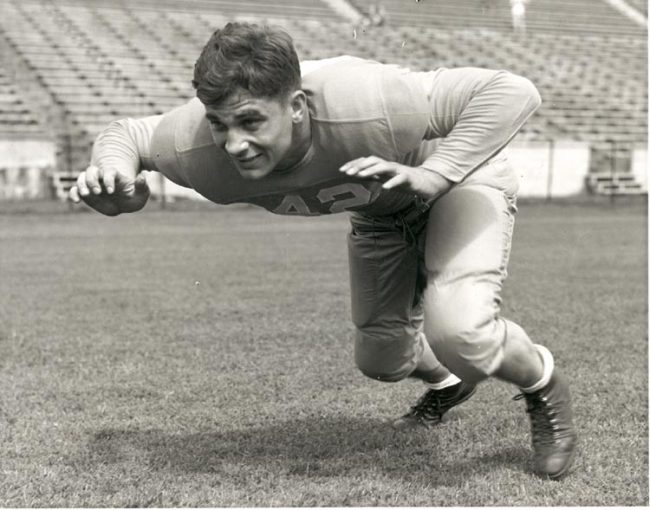

Few bubbles have burst quite so dramatically as that of Bob Suffridge. A runaway who had been scratching out his own living in the streets of Knoxville since the age of 15, Suffridge went on to be named one of the eleven best college football players of all time. He weighed only 185 pounds, but he had killer instincts and rabbit quickness and the stamina of a mule. “He was so quick, he could get around you before you got off your haunches,” says one former teammate. “Suff was the archetype of the Tennessee single-wing pulling guard,” says his friend and Knoxville Journal sports columnist Tom Anderson. Playing both ways for coach Bob Neyland, averaging more than fifty minutes a game, Suffridge was in on the beginning of a dynasty that became one of the strongest traditions in American college football: the Tennessee Volunteers, the awesome single-wing offense, “The Big Orange,” those lean and fast and hungry shock troops of “the General.” During three seasons at UT, 1938–40, Suffridge never played in a losing regular-season game (though the Vols did lose two of three bowl games, the first of many postseason appearances for the school). He was everybody’s All-American in 1938 and 1940 and made some teams in 1939. In 1961 he was named to the national football Hall of Fame, and during college football’s centennial celebration two years ago joined the company of such men as Red Grange and Jim Thorpe and Bronko Nagurski on the eleven-man All-Time All-American team. “Bob,” says George Cafego, a Vol tailback then and a UT assistant coach now, “had every opportunity to be a millionaire.”

There may be no millionaires among the Vols of that era, but there are few slackers. The late Bowden Wyatt was head coach of the Vols for eight seasons. Ed Molinski is a doctor in Memphis. Ed Cifers is president of a textile company. Abe Shires is a sales coordinator for McKesson-Robbins. Bob Woodruff is the UT athletic director.

“I guess you have to regard him as a great athlete who never grew up. It gets worse when he starts talking about the old days. He can get to crying in a minute. Some of those big guys are like that.”

All of which makes Suffridge an even sadder apparition as he drifts in and out of Knoxville society today, an aimless shadow of the hyped-up kid who used to blitz openings for George Cafego and who once blocked three consecutive Sammy Baugh punt attempts in a brief fling with the pros. Over the past twenty-five years he has tried working—college coaching, selling insurance, hawking used cars, promoting Coca-Cola, running for public office, and running a liquor store (in that order)—but something would always happen. He hasn’t worked now in about five years. He has had two heart attacks, one of them laying him up for eight months. He has engaged in numerous battles with booze, winning some and losing others. He has gone through and survived a period with pills. Now a bloated 250 pounds, he lives alone at the Cagle Terrace Apartments (he lost his wife and four kids to divorce twelve years ago, although now and then one of the children will come to see him), where he seems to have made a separate peace with the world. He made the local papers recently by protesting when two armed guards showed up to supervise a July 4 party there. (“Bob Suffridge, a former All-American football player at Tennessee, complained that elderly residents were frightened at the sudden appearance of the men with guns…. Suffridge serves on a committee to help set up socials for elderly residents and also lives at Cagle Terrace.”) He spends his time hanging around the sports department of the Knoxville Journal, going fishing with buddy Tom Anderson, writing spontaneous letters to people like Paul (“Bear”) Bryant, talking old times with Cafego and publicist Haywood Harris at UT’s shimmering new athletic plant, and sitting for hours in such haunts as Dick Comer’s Sports Center (a pool hall) and Polly’s Tavern and Tommy Ford’s South Knoxville American Legion Club No. 138.

Except for a handful of sympathetic acquaintances, some of whom have battled booze themselves, Knoxville doesn’t really seem to care much about him anymore. When a woman in the upper-class suburbs heard a magazine was planning a story on Suffridge, she said only, in a low gasp, “Oh, my God.” There is a great deal of embarrassment on the part of the university, although officials there recognize an obligation to him and have, over the years, with fingers crossed, invited him to appear at banquets and halftime ceremonies. “It’s really pretty pitiful,” says another Knoxvillian. The newspapers generally treat him gently—“He is now a Knoxville businessman,” the Journal said after his Hall of Fame selection in 1961—and mercifully let it go at that.

Even when you talk to those who know him best you get little insight into what went wrong. Says Tom Anderson: “He’s smarter than you’d think he is, and I thought for a while he was going to straighten up. But I guess you have to regard him as a great athlete who never grew up. It gets worse when he starts talking about the old days. He can get to crying in a minute. Some of those big guys are like that.” George Cafego is clearly puzzled by it all: “I don’t believe the guy’s allergic to work. I’ve seen him work.” Ben Byrd of the Journal paints a picture of a man who has always marched to a different drummer: “He used to drive into town, park his car anywhere he felt like it, pull up the hood like he had engine trouble, and be gone all day. That time Coke hired him to do PR, he got fired when they had a big board meeting and he put a tack on the chair of the chairman of the board. He doesn’t mean to cause trouble. Maybe he just never understands the situation. I mean, like when he was sergeant-at-arms for the state legislature one time and didn’t like the way a debate was going, he demanded the floor.”

Perhaps the best friend Suffridge has is a lanky Knoxville attorney named Charlie Burks, a friend from college days who is a recovering alcoholic himself and deserves some credit for the occasions when Suffridge is in control of things. “Oh, Bob’s a great practical joker all right,” says Burks. “But what do you say about him and his troubles? He’s looking for something, but he doesn’t know what it is.”

There was a time many years ago when Bob Suffridge knew exactly what he was looking for: three square meals a day and a place to sleep at night. He was born in 1916 on a farm in Raccoon Valley, then a notorious hideout for bootleggers, situated some twenty miles from Knoxville. As one of seven children he often had to help his father carry sacks of sugar and stoke the fire for a moonshine still, but that didn’t last long. Bob wanted to go to school and play football, against his father’s wishes, and one day when he was fifteen there was a big fight between the two and Bob left home. He wandered into Fountain City, a suburb of Knoxville, where he fended for himself.

“I was living on a park bench at first,” he recalls. “One day I went into this doctor’s office and got a job going in early in the morning to sweep out the building and start the fire, for two dollars and fifty cents a week. I noticed they had some bedsprings next to the heater in the basement—no mattress, just springs—and since I had a key to the place I started sleeping there.” The doctor, a Dr. Carl Martin, came in unusually early one morning on an emergency call and found Suffridge asleep in his clothes and saw that he got a mattress and some blankets. Soon another doctor hired him to clean up his office, too, meaning an additional $2.50 a week. “For two years I lived like that. I carried newspapers, worked in a factory, cleaned out those offices and even joined the National Guard so I could pick up another twelve dollars every three months. I didn’t go hungry. I was a monitor at school, and took to stealing my lunch out of lockers.”

In the meantime, he was asserting himself as the football star with the Central High School Bobcats. “Maybe I was hungrier than the rest of them,” he says. He was almost fully developed physically at the age of eighteen, an eager kid with tremendous speed and reflexes, and in 1936 he captained the Bobcats to the Southern high school championship. Central won thirty-three consecutive games, and Suffridge became a plum for the college recruiters.

Tennessee was the school he wanted. “They already had a lot of tradition. Everybody wanted to play for General Neyland.” Something of a loner, a poor country boy accustomed to fighting solitary battles, he spent every ounce of his energy on the football field. “I couldn’t get along with anybody. I couldn’t understand them.” Although he and Neyland were always at odds, there was a curious, if unspoken, mutual respect between the nail-hard disciplinarian and his moody, antagonistic little guard.

Once the last cheers of the 1940 season had died, Bob Suffridge appeared to have the world in his hands. He earned a degree in physical education (“l guess I thought maybe I’d be a coach one day”), married a UT coed and signed to play with the Philadelphia Eagles. He was named All-Pro for the 1941 season, but more important than that was what happened in the last regular game of the year. It was played on Sunday, December 7. “That was the day I blocked three of Sammy Baugh’s punts,” he says, “but nobody paid any attention the next day. At halftime somebody had come into the dressing room and told us Pearl Harbor had been bombed by the Japs. I’d have been the hero of the day except for that.” Suffridge immediately joined the Navy.

In retrospect, that announcement of the attack on Pearl Harbor was the pivotal moment in Suffridge’s life. As executive officer on a troop attack transport, he suffered only a slight shrapnel wound to his right leg and went through no especially traumatic experiences. What hurt was the timing of it all. He was twenty-five and in peak physical condition when he went in, but a flabby thirty when he came out. He tried to make a comeback with the Eagles during the 1946 season, but he weighed 225 and was soon riding the bench. The bubble had burst, and he was confused. There would be occasional periods of promise, but once the 1950s came it was a steady, painful downhill slide.

Giving up on pro football, he tried college coaching—at North Carolina State under ex-Vol great Beattie Feathers, and at the Citadel under his old high school coach, Quinn Decker. Next he went to work as an insurance agent for a company in Knoxville, and after three good years he decided to open his own agency. The business did all right for a while, thanks to his name and his contacts around town, but he started in on the pills and the booze and soon had to unload it. (“I sold out for a good profit,” Suffridge says, but others say the business fell flat.) And then the wandering began. He went to Nashville to sell used cars. He blew the public relations job with Coca-Cola. He was divorced by his wife in March of 1960, a year before his election to the football Hall of Fame. The chronology of his life became a blur after that. He ran for clerk of the Knox County court and nearly defeated a man who was considered one of the strongest politicians around and who later became mayor of Knoxville. He had to be literally propped up, to the horror of UT officials, at numerous occasions when he was being paraded around as the Vols’ greatest player. He drifted to Atlanta, where, for a year, he drank more than he sold at a friend’s liquor store. He worked briefly for the state highway department. Finally, around 1965, shortly after the private publication of a boozy paperback biography entitled Football Beyond Coaching—composed in various taverns by Suffridge and a local sportswriter known as Raymond (“Streetcar”) Edmunds—he suffered two heart attacks.

“Yeah, me and Streetcar had a lot of fun with that book,” Suffridge was saying. It was almost dark now, and we had driven out to Tommy Ford’s American Legion club. This is the place where Suffridge’s Hall of Fame plaque had hung majestically behind the bar for several months before outraged UT officials finally got it for display in a glass showcase on campus, and the place where Suffridge has spent many a night locked up without anybody knowing he was there. He was saying farewell to his friends, for in the morning he would leave for a month’s vacation at Daytona Beach as the guest, or mascot, of his attorney friend Charlie Burks and a doctor from Jamestown, Tennessee. He had dropped a couple of dollars at the nickel slot machine, and now he was sitting at the bar, playing some sort of game of chance for a bottle of bourbon.

“How’d the book do?” somebody asked.

“Damn best-seller,” he said. “Hell, I made about seventeen thousand dollars off that thing. Sold it for two bucks. We’d have done better than that if we hadn’t given away so many. I’d load a batch in the trunk of my car and head out for Nashville, Memphis, and Chattanooga. Sell ’em to people I knew at stores and in bars. Then I’d come back home and find Streetcar sitting in Polly’s Tavern and I’d ask him how many he’d sold while I was gone and he’d say he’d gotten rid of two hundred. ‘Well, where’s the money?’ I’d ask him, and he’d say he gave ’em away. Street was almost as good a businessman as I was.”

“Go on, Bob, take another chance,” said a blonde named Faye.

“Another? Honey, that’s getting to be expensive liquor.”

“Price of liquor never seemed to bother you much.”

“Guess you’re right about that.” A phone rang. “Get that, will you?” he said. “Might be somebody.”

And so it goes, an evening with Bob Suffridge. They are all like that, they say: aimless hours of puns and harmless practical jokes and, if the hour is late enough and the pile of beer cans high enough, those infinitely sad moments when his eyes water up as he talks on about the missed opportunities and the wasted years. How can anyone pass judgment, though, without having come through the same pressures he has? I came into the world a poor boy, and I’m still a poor boy. What a man has to do is be grateful for the good times and try to live with the bad.

We were finishing steaks at a motel dining room, washing them down with beer, when the waitress could stand it no longer. A well-preserved woman near Suffridge’s age, she had been stealing glances at him throughout the meal. She finally worked up her nerve as she was clearing the table, turning to me and saying with an embarrassed grin: “Excuse me, but didn’t I hear you call him Bob?”

“That’s right.”

“Well, I thought so.” For the first time she looked directly at Suffridge.

“You’re Bob Suffridge, aren’t you?”

He wiped his mouth and said, “I guess I am.”

“I was Penny Owens. I went to Central High with you.”

“Penny….?”

“Oh, you wouldn’t remember me. You never would even look at me twice when we were in school.”

They talked for a few minutes about old times and former classmates.

There was an awkward silence. “So,” she said, “ah, what are you doing now, Bob?”

“Nothing.”

She flushed. “Oh.”

He suppressed a belch and then looked up at her with a mischievous grin. “You want to help me?”

“Aw, you.”

“Awww, you.”

From Football: Great Writing About the National Sport, edited by John Schulian and published by The Library of America. Copyright © 2003 by The University of Alabama Press. Used by permission.

[Photo Credit: UT Sports Information]