“I have a problem,” I said.

“How’s that?” Tu Sweet asked.

“I’m about to be dead.”

It was early in the morning. Tu Sweet, the self-styled “Black Fred Astaire and Nureyev of the Hustle,” was relaxing in my neighborhood bar, fresh from a night in the disco. Breakfasting on Grand Marnier and Coca-Cola, he studied his picture in a beat-up magazine, which never left his person. “How dead is dead?” he asked.

“Severely.”

“What for? Have you committed some rashness?”

“I agreed to write a story on 42nd Street,” I said. “I didn’t want to. Right from the gitgo, I thought it injudicious. But my young lady forced me. When I tried to back out, she called me a mewling, cringing travesty of manhood. She said I had the heart of a flea-ridden cur.”

“So?”

“So I weakened. And now I’m trapped. I must live through 24 hours, one full cycle, down on the Strip. What’s more, I must go to the limit. No cheating, no ducking or dodging—come what may, I must endure.”

“Twenty-four on 42,” said Tu Sweet. “So where’s your problem?”

“I am a mewling, crippling travesty of manhood. I have the heart of a flea-ridden cur.”

“And you fear that you’ll wind up extinct?”

“That is the truth,” I said.

Tu Sweet took his time. Reluctantly laying aside his magazine, he made a series of minute adjustments to his collar, shirt cuffs, tie. He ordered another shot of breakfast, contemplated his image in the backbar mirror. When at last he broke silence, his tone was almost biblical. “Have no fear,” he said. “Right here, at your service, you possess the number-one expert on the Street that was ever born or created. For a small consideration, the very merest token, not only will I keep you safe, but I’m willing to act as your guide. I will show you everything you dreamed of and plenty more you didn’t. Just stick with me and in 24 hours, you have my guarantee, you will know the Ultimate.”

I asked no questions; there was no point. Head bowed in resignation, I stuck my hand in my jacket pocket. “How much?” I asked.

“For the Ultimate?” said Tu Sweet. “A 50 would suffice.”

“Thirty-five.”

“Forty.”

“Done,” I said.

And we set forth.

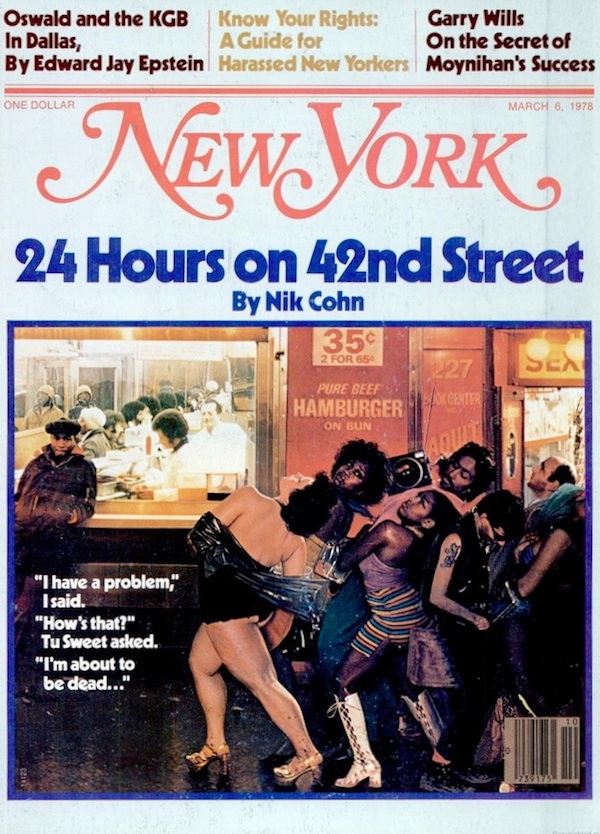

It was 9 a.m. when se started. Rain was falling steadily; the air was as clammy and chill as an undertaker’s handshake. Still, this was Saturday morning, the main day of the week, and the street was buzzing, regardless.

Between Seventh and Eighth, all along the Strip, the sidewalks were jammed solid. This was the vortex, the central bedlam of cinemas and sex shops, burlesques and discount boutiques, greasy spoons, peep shows, dirty bookstores. Tu Sweet called it Hustle Heaven.

No doorway stood empty. Like an open box, each framed its own performers. Motionless, expressionless, they posed like dummies in a waxworks, eternally frozen in waiting.

Between them, they formed a frieze, a kind of skid-row tableau vivant; black hookers in hot pants and lacquered wigs; body builders and midnight cowboys; tattooed sailors in leather; evangelists with pamphlets or sandwich boards; polaroid photographers, two bucks a shot; pubescent Puerto Ricans; Superflies in fancy hats, murmuring promises of cocaine, mescaline, speed; children who stared without blinking; all-Americans with blue eyes, bulging biceps, and Man-Tan golden flesh; furtive men in overcoats, growing old; junkies and transvestites, assorted; policemen in twos, idly twirling their nightsticks; young girls from Kansas, their jeans as tight as sausage skins; ex-fighters, lost in fog; pimps and enforcers; defective derelicts and scattered tourists, gawking.

It was a familiar cast. So familiar, in fact, that it almost seemed faked. These faces, all these set poses and pitches—over the years, I’d seen them aped in so many movies and plays, such a multitude of TV potboilers, and even the genuine articles now looked staged. At any moment, as we cruised, I half expected the Strip to fade and be replaces by commercials pushing diapers, paper towels, detergents.

Tu Sweet took charge from the outset. This was his beat, his true homeland. The moment that his feet touched the Strip, he put more jut in his strut, an extra glide in his stride, and he started to dictate. “First of all, the rules,” he said.

“What rules?”

“The ways to stay alive. Down here, you understand, not everyone is a gentleman, and accidents can happen.That has to be known. But I have the five golden rules. Just follow them clean, and your ass need fear no evil.”

We stood on the corner of Eighth, where we got wet. In a puddle the size of a small pond, printed pamphlets floated at random. Each bore the slogan “You don’t have to be Jewish to love Jesus.” “Rule 1: Be prepared,” said Tu Sweet. “Rule 2: Beware of strange bathrooms. Rule 3: When in doubt, don’t. Rule 4: Unto thine own self be true. Rule 5: Smile.”

It sounded simple: I felt encouraged. Ambling back and forth along the Strip, three times east, three times west, I raised my eyes from the performers and began to contemplate the cinema awnings. According to my instant spot-check, 38 movies were playing on this one block. In particular, I was tempted by Mast of the Flying Guillotine, or, better yet, by Love Slaves Tortured to Blood Dripping Death in Sanctuary of Satan. But Tu Sweet wouldn’t let me go in. He said that work came first. After all, we were on a mission. “So were do we begin?” I asked.

“Sex,” he replied. “Where else?”

For $3 each we paid our way into an X-rated movie. The film dealt with dairymaids, farmhands, and high jinks in haylofts. At one point, a man and two women frolicked together in a pigsty. This made me think of my home in England and my prize sow, Gertrude, my favorite Welsh White, who once won third prize in the Hertfordshire County Show, Open Class. Homesickness overwhelmed me.

After the film, there was a live performance. A thin girl with very white skin appeared onstage, accompanied by a boy with long, lank hair and lots of teeth. They took off their clothes, folding them neatly. Then the boy lay down on a mattress, staring at the ceiling, and the girl performed fellatio.

It seemed like hard work. The girl as methodical, earnest, determined, but the boy showed no reaction. The cinema was dark and airless and smelled of disinfectant. From time to time, the girl would draw back and massage her jaws, to ease the cramps, before resuming her labors. The audience kept perfectly still, making no sound. So did the boy onstage.

Warmth and fug made me drowsy. As the performance dragged on, with no apparent end in sight, my eyes grew heavy, and I started drifting. The man beside me was already sleeping, gently snoring. I thought of corned-beef hash and fries, of chocolate-fudge sundaes. On my right, Tu Sweet complained of a toothache.

Finally, after eight minutes and 53 seconds, the girl achieved success. The boy gave a few feeble twitches and raised one hand, fist clenched, in the air. There was a round of polite applause. Rising from the mattress, the boy and girl smiled and waved good-bye.

Afterward, I saw them in a nearby cafeteria, retarding themselves with beef-filled turnovers. Close up, apart from a few scattered pimples, they looked as clean-cut, as antiseptic, as newlyweds in a TV commercial advertising dandruff shampoo.

They were married and in love. The girl came from Holland, and the boy played rock ’n’ roll. Sooner or later, they were sure, he would become a star. But right now money was tight. A few months ago, they had been reduced to living in the back of a van. Then they strolled past the X-rated cinema and decided that, in the last analysis, sex was more fun than starvation.

Conditions were not easy. To begin with, they had worked four shows a day, seven days a week. That had been exhausting. But they had stuck it through, they’d won their spurs, and now they reaped the rewards. Their wages had upped, and their schedule cut in half. Audiences were respectful. So were their fellow professionals. For $40 a day, tax free, they had no complaints.

The only problem was the law. They had already been busted twice. True, the cinema paid their fines. But the experience disturbed them just the same. The day after the last raid, his nerves still on edge, the boy had failed to perform. Still, that was life, he said. You win some, you lose some: che sarà sarà. In a few months more, they would have saved enough to quit. Then he could concentrate full-time on his music. His day would come. All the hard work, all the sacrifice and patience would be rewarded. “Sometimes the road gets rough. Sometimes you feel like giving up. But you’ve got to keep on believing, no matter what,” he said.

“You must have faith,” said the girl.

“Faith,” said the boy. “And love.”

Back on the street, it was still raining. Mist had descended, so thick, such a deep and dirty yellow, that the whole Strip seemed shot in sepia.

In two hours, none of the performers had moved. Everyone was selling. Nobody bought.

Between Sixth and Seventh, we passed a serious bar. “Refreshment are served,” said Tu Sweet, and he led me inside a long, dark room, warm and snug as a neon womb.

It smelled strong of jail. The room was jammed full of hustlers—dealers, strong-arms, salesmen of all descriptions. Transvestites clustered round the jukebox, miming to Donna Summer. A white man with hairy legs who wore a plaid miniskirt, peroxide wig, and ankle socks stood by the telephone, weeping. And two solemn blacks sat in a far corner, with heads close together, discoursing in conspirator undertones.

These men were immense. They must have weighed 270 pounds apiece and were built like defensive tackles. The face of one was crisscrossed by so many scars, it looked like a ghetto road map. As for the other, he had known Tu Sweet in jail.

It was barely three o’clock; only six hours had passed, and already I felt used up.

Understandably, Tu Sweet showed deference. “Didn’t mean to interrupt your conference,” he said. “We just chanced to be passing.”

“No interruption. None at all,” said his friend, whose name was Luke. “Me and Junior, we was just discussing the best way to cook veal. I said rolled in bread crumbs, real thin slices, then panfry and serve al limone.”

“Sweet wine sauce is better,” said Junior. “Just take your tender milk-fed meat, sweet and soft as a virgin pussy. Then add Marsala wine. Right there, you got heaven.”

“Or maybe stuffed with ham and melted chases. Cordon Bleu,” said Luke. “That ain’t so shabby, neither.”

But Tu Sweet was not impressed. His face turned sour, as if his Grand Marnier had suddenly turned to Angostura bitters. “Gourmet jive,” he said. “What’s wrong with pork chops and sweet potatoes, gravy, hot biscuits, maybe just a mite of collards on the side?”

Luke looked him over, without expression. So did Junior. Between them, weighing more than a quarter ton, they made Sonny Liston look like Barry Manilow. There was an icy silence. Then Luke produced judgement. “Medallions, scalloping, sautéed with mushrooms,” he said. “That is my final ruling.”

Out on the Strip, the crowds overspilled the sidewalks. Every few yards, we passed a sneak game of cards, played on a cardboard box. But Tu Sweet was not tempted. “That Luke, he said, “he gives me disgust.”

“How’s that?”

“The nigger’s lost his soul. When we was upstate, he’d have eaten slop. But now that he’s out, his hat’s run away with his head. Sautéed mushrooms! Veal Cordon Bleu! Just because he’s a faggot, he thinks he’s Jackie Onassis.”

“What was he in for, anyhow?” I inquired.

“He grew unruly with a hatchet.”

Next we went to Show-World, a sexual bazaar on Eighth. Outside, posters advertised the forthcoming attraction, a show called Bizarre Burlesque, starring Pregnant Polly, the Enemas Queen, and Tina Toilet Tonsils.

The interior was modern, bright-lit, spacious. Among the regulars on the Strip, so Tu Sweet informed me, it was considered a palace, its standing second to none. “Clean floors, fair prices, and women wall to wall,” he said. “What more could one man desire?”

Almost everything cost a quarter. For that token fee, you locked yourself in a closet the size of a telephone booth and watched home movies Somewhere above your head tapes played simulated orgasms over and over again. Then there were magazines to browse through, all kinds of toys to be examined. More especially, there were peep shows upstairs, where you peered through a porthole at two ladies, one white, one black, who contoured themselves to music. Reclining on a circular bed, naked, they spread their sexes wide open, alternatively simpering and yawning. If you showed approval, one of them rewarded you by rubbing herself up against your porthole. Meanwhile, reflected in the back mirror were the faces of twenty men in a semicircle, twenty heads bobbing, 40 eyes staring, each man trapped behind a porthole of his own, like so many goldfish in bowls.

That was not all. For another dollar in quarters, you could also pick up a phone and talk to a Real Live Woman who sat behind a plate-glass window and served as your personal slave. Whatever you told her to do or say, within reason, she obeyed. So long as you did not get violent, she performed without question, and her smile never wavered.

The prospect was not soothing. Suddenly, lost in this sea of sideshows, I was flooded by nightmares of long-ago funfairs. All through my childhood, my greatest deeds were ferris wheels, Tilter Whirls, and roller coasters, which I knew were created to destroy me. Yet, time after time, I would force myself to endure them, eyes shut and stomach lurching, white hands clutching the rail. The thought of a Real Live Woman gave me much the same sensation.

There was no question of escape. I had my duty to perform, my promises to keep. So I went inside a booth and put my money in the slot. Beneath my feet, as I locked the door, I felt something wet and sticky. The smell made me gag.

After a moment, a blind was raised, like a plastic portcullis, and I was faced by a muscular blonde, some twenty pounds overweight, with eyelashes like windscreens and a vivid pink scar on her stomach. She looked serene, benign, cowlike. Waiting for me to begin, she smiled encouragement and blew out gum in a puddle, like a miniature bladder.

That was when I froze. Instead of picking up the phone and delivering terse instructions, I could not move or make any sound. Plunged back to age eight, imprisoned in a different form of Ghost Train, all I could do was shut my eyes tight and hold my breath, blotting out the pink gum, the pink scar, the spread pink sex.

For a long time, it seemed, I reminded in darkness and silence. Then I opened my eyes, and the blonde was gone. The plastic blind had shut her out. Shaking, I stumbled out into the passage, where Tu Sweet was waiting. He said I’d be gone for two minutes, no more. But I did not believe him. “I aged in there,” I said.

“That could be done; I don’t deny it,” he replied. “When a man is less than a man, he grows old fast.”

It was barely three o’clock; only six hours had passed, and already I felt used up. For $10 cash, back on the Strip, I bought some cocaine from a man with a walleye. When I tried it out, bent double in a hallway, it revealed itself as lactose mixed with chalk.

The hours dragged slow. Aimless, we kept cruising, nothing else to do. We mooched up and down in the rain, examining the stills outside dirty movies.

It grew dark and the neon came on. But the performers in the doorways did not change.

Close to the Seventh Avenue subway, there was a preacher called Sister Pearl. Big, black and possessed, she rocked her body in frenzy, she hollered and spoke in tongues. Except for a few “Hallelujahs,” hardly any of her words could be deciphered. It did not matter. Nobody stopped to listen.

Afterward, when the preaching was done and her soul had been soothed, she leaned up against the subway railing to gather her breath. In repose, all hysteria left her; her smile oozed lazy and slow. Nothing bothered her, not public indifference, not the wet and the cold, not even her own incoherence: “What’s the use in making sense?” she said. “Far better to just burn. Fan the flame or the fire will die. Then the Lord spews you forth from his mouth.”

Every doorway that I passed, I entered automatically. Some contained sex. The rest were filled with alcohol.

A patrol car sped by, siren shrieking. Wiping off her her hands on hr black dress, Sister Pearl hung her purse on her wrist, disappeared inside the subway, and we went back to floating. This was the rush hour; Saturday night was just warming up. Outside the Super-Fly Boutique, a youth in a yellow-spotted bandanna barged hard against my shoulder, hoping to pick my pocket. In jumping clear, I blundered into a mongoloid, who cowered against a wall, a dog about to be kicked. I told him I was sorry. But he did not see or hear me.

Human flotsam spilled everywhere, swarming, devouring, like Triffids. We sought refuge in a luncheonette. Lounging against the counter, devouring hot dogs with mustard, three lawmen were discussing Farrah Fawcett-Majors, her assets and debits, her sorrows, her joys, her nipples. The jukebox played “My Way,” and the dealers offered cocaine, mescaline, speed.

We moved through the crush. We struggled, we shoved. For perhaps the twentieth time since morning, we passed the lines of sailors and midnight cowboys, the weight lifters in black leather, the hookers in their hot pants. “What next?” asked Tu Sweet.

“I need to be drunk.”

“Fan the flames. Or the fire will die,” he said, and we set to work in earnest. We drank brandies in a Chinese restaurant, bourbon and beer in the Golden Dollar Topless. Upstairs at the Roxy Burlesk, we sat by the edge of the stage and downed ourselves in rye. A few inches in front of our faces, assorted bodies coupled, gymnastic and inexhaustible. But now I hardly noticed. Blurred by repetition, sex had already turned into background, a style of human Muzak.

Outside, a street photographer stopped me and took my picture. He said he came from North Africa. His father was a big man in Algiers, an international skydealer. This did not sound correct, but I didn’t care to argue. “Sky-dealing. That must be nice,” I said.

“Nothing can be better,” said the photographer.

While my image was developing, he whistled “Feelings,” all smiles. But when the picture emerged, he winced. “You no smiling,” he protested. “Mister, you sick?”

“I’m dying.”

“In that case,” said Tu Sweet, cutting in fast, “let me show you the Terminal Bar.”

He did not jest. On the corner of Eighth and 41st, right across from the Port Authority, there was a bar of just that name, and its title proved well earned. Everywhere that you looked, there was loss, stock symbols of booze and despair. Faded boxing pictures in the windows, rank stench outside the restroom, broken glass on the floor. A painted sign, announcing TAKEE OUTEE. Grime thick as axle grease. Men drinking in a line, seeing nothing, alone.

The man behind the bar, very large and very black, had once played professional football. Even in retirement, he could crush rocks with his handshake alone. “This man, he so tough,” Tu Sweet said, “he chews pig iron for breakfast and spits it out as sharp as razor blades.”

We drank whiskey, we drank rum. For purposes of research, moving left to right along the bar, we then progressed to vodka, tequila, gin. Tu Sweet spoke of his schemes, his dreams, his hopes, his fears, and I thought about Gertrude, my prize sow. Somewhere behind our backs, an altercation started. There was a dispute about Ireland. Voices were raised, obscenities exchanged. In due course, fists were raised. There was a dull thud. Then a yep of pain. Then a crash. “It’s late. We really should be going,” I said. But Tu Sweet was already gone.

Later on, when I asked him why he’d fled, he told me that violence always made him think of his mother. “As soon as I hears breakage, I just got to run downtown and call her, to tell her how much I love her,” he said. “You might call it a primeval need.”

“I might?”

“You could look it up.”

Left alone, I drifted without looking. Every doorway that I passed, I entered automatically. Some contained sex. The rest were filled with alcohol.

In time, progressions grew blurred. Time kept jumping, and only fragments survived. In the bathroom of some all-night cinema, exactly that strange bathroom Tu Sweet had warned me against, I purchased some black pills, some red pills, and some green pills, and I swallowed them in a handful. Mixed all together, they made me dizzy, and then they made me laugh. Sitting in the foyer, I started to make noise. Someone told me to keep quiet. Rising, I tried to punch him, but I missed and fell down instead.

Midnight came. The Strip did not shaken its pace. Of all the morning performers, only the lawmen and evangelists had abandoned their posts. No one else can afford defeat.

I rambled. I got lost. When I tried to play cards, across a cardboard box, I kept forgetting the rules. So I sheltered in Starship Discovery 1, close to the corner of Ninth. The man on the door told me that this was the biggest and hottest, the most prestigious discotheque in all Manhattan. But when I went inside, everyone came from Jersey.

It was just another disco. There was din and heat and flashing lights, a dance floor like a football scrimmage, universal uproar. Instantly exhausted I slumped in a corner, where I tried to recover focus. My eyes hurt; I could not breathe. Then a girl wandered by, wearing drawstring pants, mirror glasses, open-toed sandals. Her skin was bad, and she had no chin. In any case, she spilled her drink in my lap, and I was grateful.

She said her real name was Charlene, but I could call her Libra. She had myopic green eyes, passion-pink toenails. I suggested we catch a plane, maybe to Vegas to play 21. Or else to Acapulco, where she could scuba dive. She said that was real neat, but first she must go to the bathroom. I promised I’d wait forever. Then she was gone and I forgot.

I walked. I kept on drinking. When that was done, I went to Nathan’s, on Times Square, to straighten up and let time pass. I piled a tray high with hot dogs and chili dogs, onion rings, fries, and proceeded to gorge myself in ritual self-punishment. Two o’clock came and went. Against all odds, I started to feel stronger. Then an Arab approached in a three-piece sulk suit, with a diamond tiepin and serious gold on his fingers. He called himself Ahmed and swore that he could provide me with anything, absolutely anything, that my heart desired. “Your wish is my command,” he said. “Just name your dream, and I will make it come true.”

“Oblivion,” I said.

“Alas, that is not possible,” he replied. “But I can find you cocaine, mescaline, speed.”

Back on 42nd, Looking for Mr. Goodbar was playing at the New Amsterdam. Given the time and place, I could think of no more suitable film.

So I paid my money; I entered. I found myself in a fantasia, a truly heroic madness. According to the doorman, it had been home to The Ziegfeld Follies. Now it had fallen on scuffling times. The décor was much scarred, and so was the clientele. But the magnificence was indestructible. There were massive carved-bronze elevators; sculpted stone frescos of scenes from Shakespeare and Wagner; green marble stairways, soaring to the empyrean; floors of patterned marble; nymphs, satyrs, wizards, elves; walls gilded or bronzed; a granite fireplace the size of a small house. Every inch of available space, it seemed, had been embellished, in some way transmuted. Door handles turned into centaurs and light holders became Egyptian goddess. Junkies slumped on baronial thrones.

I went upstairs and sat in the balcony. Everybody around me was black. Discarded hot dogs, cigarettes, and soft drinks formed a swamp underfoot. Somewhere far above me, I could just discern a vast vaulted ceiling. But the aisles were dark and rank, and I took the first seat I found, close to the back where I could not be trapped.

The film was almost over. In any case, the action left me baffled. For reasons which escaped me, everyone on the screen kept screeching and yelling. This confused and alarmed me, and made my head ache. So I went to hide in the bathroom.

When I returned, my seat had been usurped. In the darkness, it was impossible to make out the intruder in any detail, but I sensed something female, and white. Too booned to protest, I sat down beside it and dragged my attention back to the screen. Nothing made sense; my confusion only deepened. Then a hand touched my knee, paused for a moment, and started to climb my thigh, very soft. It disturbed my concentration and I moved away. Shortly afterward, the film reached an end.

The lights when up; I looked along the row. Sure enough, my neighbor had been female and white. From this distance, she looked about 40, small and well dressed, essentially demure. She wore white gloves, and she looked straight ahead, as if I no longer existed. She seemed to be waiting.

All around her there we blacks at jive. But she did not move and she did not seem to notice. After a few seconds, a white man appeared at her side. He was tall and muscular, and he wore a dark uniform, complete with peaked cap, like a chauffeur. Reaching out his right hand, he placed it behind the woman’s back; one hand peeled beneath her armpit. Then, without the smallest sign of effort, he lifted her up, cradled in the crook of his elbow. Her head lay against his shoulder, and he carried her away. She had no legs.

It was almost three; at last, the Strip was winding down. From now on, the main action took place in the all-night movies, and the street itself thinned out.

Only one game of cards was left. Half the doorways stood empty. Even so, cars still cruised in a steady stream, their windows lowered halfway. The eyes that peered out were impassive. Surveying the remaining performers, they checked, judged, priced, discarded, all in the same instant. No desire was involved; no possibility of pleasure. Like sexual accountants, they merely made their calculations, balanced their books, and moved on.

Right next to Amsterdam, I saw a sign that said CHESS AND CHECKERS CLUB OF NEW YORK. It sounded restful. So I walked down another deserted hallway, and I climbed one more flight of stairs. When I reached the top, I found sanctuary.

I entered a room that was large and bright and clean, the image of decorum. Beneath a glass counter, there was a collection of antique cakes and sandwiches, neatly wrapped. Coffee was also served. On the walls, there were pictures of sunlit valleys, of grasslands, and of blue skies.

Scattered about the room, men sat at Formica-topped tables, pondering the complexities of backgammon, Scrabble, chess. Most of them wore suits and ties, and none of there was young. Sages, elders, they spoke only when they had to, and then in undertones. Nobody laughed, no one swore. These were serious men.

Close beside the glass counter, a wino slouched in an upright chair, half asleep. I sat down beside him and watched the play. Cards slapped on the tables, setting up irregular rhythms; dice rattled like snakes; the players murmured, droned. In time, lulled by these calm rituals, I lapsed into semi-stupor.

When I came to, it was past five. None of the players had changed position, and none of the games was resolved. In this room, which never closed, time seemed suspended. You came, you played, you remained. Outside, on the Strip, there was madness. Here you were kept safe.

Once again, I went back on the street. The rain had stopped, but it was cold; the wind whipped harsh. All the bars were closed; only the hardiest performers, or the most despairing, clung on. I couldn’t face another all-night movie, and I would freeze if I stayed outdoors. So I shambled back to Show-World, where I locked myself in a booth with Oriental Lesbians. They smiled nicely; their bodies were not deformed; they offered no threat. Therefore, I did not leave them. Speed-racked, close to tears, I ran and reran their loop, for comfort and companionship, until my last quarter was gone.

Afterward, there was nothing left but the Port Authority. I dragged myself down Eighth very slow. Apart from a few drunks, the sidewalks were deserted.

Every door was locked, every window barred. I was alone.

According to Tu Sweet, these blocks are known as the Minnesota Pipeline on account of numberless midwestern girls who clamber down off greyhounds, suitcases in hand, $20 in their purses, and go straight to work in the doorways, because there is nowhere else to go, nothing else in the world they can do.

True enough, just as I reached the corner of 41st, I was stopped by a girl’s voice coming out of a semi-darkness. “Mister,” it said, “why don’t you enjoy some fun?”

The girl could have been eighteen, twenty at the most. She looked underfed and anemic, inescapably plain with thin reddish hair and too much mascara. She wore a white plastic raincoat, tightly belted, but her legs were bare underneath. Her nose had been reddened by the cold. She said that her name was Cindy.

She led me to the Hotel Elk, right next to Starship Discovery. It was a squat brownstone, overlooking Ninth. We toiled up many flights of stairs, past a sign that said NO VISITORS. The light was dim. A small girl sat on the stairway, outside her room, waiting for her parents to finish making love. Three radios played clashing music. We kept on climbing, and we reached a brown door. Cindy took me inside.

She lived in a small, long room, which contained a bed and a bedside table, two chairs, one of which had broken leg, and a washbasin. The blind, cracked and ripped, had been permanently lowered. There was a broken mirror.

All of this made Cindy feel embarrassed. She was new in town, she said, and had yet to find a sponsor. If she had had any choice, she would not have lived like this; it was not her natural style. But she could afford nothing better. “It’s cheap,” she said. “So am I.”

She took off her clothes. She lay on the bed and waiting.

“Where do you come from?” I asked.

“I was born in Kansas. Then I was raised in Ohio.”

“What made you leave?”

“I got too old to stay.”

Conversation did not come easy. Cindy was polite; clearly, she meant to please. But she suffered from some inner cancellation, a curious blankness, almost like a sleepwalker. Her voice was toneless, as if she were forever repeating lessons, and all her answers came out in subtitles, staccato, no more than a few words long. If I closed my eyes, she sounded like a recorded message.

Outside, it was just starting to get light. In the next room, a man woke up and started swearing, methodically, without inflection.

“New York gets cold. Not as cold as Ohio. But cold,” Cindy said. “Sometimes it gets so cold, I can’t even sleep.”

“You could move somewhere warmer.”

“I couldn’t. To move, you have to be protected. But I’m not protected. Every girl is protected by someone. But I’m not protected.”

“It’s true,” I said. “New York can be hard.”

“It’s so large. So large.”

“It is.”

“It’s the biggest place I ever was in.”

“Don’t you have any friends?”

“Friends cost money.”

For $25, she let me stay until morning. Stretched out across the bd, she lay on her back, eyes wide open, looking up at the ceiling. I tried to sleep but couldn’t. Feverish, I tossed and rambled. I sweated. Cindy never stirred.

When the time came to leave, she kissed me on the cheek, vey chaste. Makeup was smeared across her eyelids and mouth; her nose was still red from the cold. “I hope you enjoyed your fun. Please come again,” she said.

“Thank you.”

“You’re welcome. Have a nice day.”

One last time I walked up the street, back toward Times Square. It was Sunday morning, when bars do not open until noon, and there was nobody around. The Strip itself was abandoned, a tenderloin Marie Celeste. Of all yesterday’s performers, that massed throng, not one remained.

My 24 hours were up. In celebration, I bought myself some coffee and a jelly doughnut, take outee, to go. Then I made my final tour of duty, from Nathan’s to the Terminal Bar, from Amsterdam to Show-World, via the Roxy Burlesk and Golden Dollar Topless and Super-Fly Boutique. Everything was shut or deserted. I had outlasted them all. Now I was free to go home.

I stood on the corner of Eighth, waiting for a cab. Washed up on the curb like sea wrack, there were the same abandoned pamphlets, the ones that said “You don’t have to be Jewish to love Jesus.” I stooped to study the small print. As I did so, Tu Sweet appeared, emerging from the subway right across the street.

He looked indecently rested. Freshly laundered, showered, he sported a flash plaid jacket, knife-edge flannels, patent pumps. When he reached my side, he slapped me five. “What’s the action?” he asked.

“Nothing much. Just a little sky-dealing,” I said.

“Is that a fact, Jewboy? I thought you perished for sure. Me and your young lady, we spent the whole night on our knees, lighting candles. We even planned the wake.”

“I hate niggers,” I said.

Together we trundled up the avenue. Pale sunshine was breaking through the gray; the cold had begun to ease. As we strolled, the first few performers emerged, greeting the new day. It looked like another lazy Sunday.

I started to feel better. I was still carrying my coffee and jelly donut, safe in a large paper bag, and I let myself dream of breakfast. Just for a moment, I relaxed. And that was my final undoing.

The kayo, when it came, was a one-punch job, swift, clean, and total. Outside a Blarney Stone, a drunken woman was sitting on the doorstep, her head clasped in her hands. As we passed, she seemed to be staring into space, oblivious. Then somehow her eye caught mine, and she jumped to her feet, incensed.

Red-faced with fury, hands shaking in wildest outrage, the woman pointed at my face, and then at my paper bag. “Imposter! Fraud!” she cried. “You’ve got nothing in that bag. And may God be my witness, you never will.”