“Yeah,” I said into the telephone.

“Diane Shah?”

“Yeah.” It was ten-fifteen in the morning. I was in the office filling out an expense report, a chore that always makes me grumpy. I am never in the office at this hour, so I figured whoever was calling wasn’t anybody I wanted to talk to.

“This is Cary Grant.”

“Uh-huh.” Had I eaten lunch on Monday and, if so, where was the bloody receipt.

“And I just wanted to tell you how much I enjoyed your column today.”

I laughed. “Thank you.” Whichever of my friends was doing this had “the Voice” down remarkably well.

“Poor Reggie. I know exactly what he went through.”

The column had been about a dinner with Reggie Jackson, and how the rudest people had come barging up to his table, blowing cigarette smoke in his face, pushing his plate aside, demanding autographs. The character on the end of the line began talking about the perils of celebrityhood.

Suddenly, I was pressing my ear into the phone. There was a loud banging, either my knees knocking or my heart pounding. Then a faint voice was interrupting. Whispering, “Excuse me… but are you really Cary Grant?”

Even so, given this, gearing up to call him back was not easy.

For nine months, no, a year, magazine editors drummed the steady beat of my telephone number on their dialing pads. “Cary Grant!” they cried. “We must have Cary Grant!”

And I would hang up and I would look at my calendar and I would pick a day, maybe Thursday, put it off a little, you know, and I would write carefully in ink, “Call C. Grant.” Or maybe I would just sit there and stare at my phone for a while before lifting the receiver as if it were a piece of Limoges china, and taking about an hour to push each of the seven digits and then taking a deep breath as someone at the Grant residence put me on hold for a very brief moment. Then….

“How are you today!”

Just like that.

Over the lines came that wonderful lilting voice that could cheer up the dead pharaohs, that gravelly British-tinged voice that had impelled President Kennedy to call up from time to time and implore, “Say anything, I just want to hear your voice.”

Now that voice was chatting amiably away as if he had nothing better to do in life than sit there taking my phone call.

And so it would go like this, month after month, until at last we finally agreed to meet for a day at the races at Hollywood Park.

Part I: A Day at the Races

“How much are we betting today, darling?”

This is Barbara Grant, beautiful, impeccable in a peach suit, her race card and The Daily Racing Form spread on the table in front of her, smiling at her husband. It is a ritual, a private little joke, the How-much-are-we-betting-today? inquiry. Because as Grant once explained over the phone, “I make $2 bets, you see, because they won’t take a dollar fifty. I’ve tried.”

He reaches into the pocket of his exquisite olive-green suit (the crisp white shirt is tinged ever so slightly with pink; the tie is black) and removes a roll of money. Carefully, he peels off a new $50 bill, then two twenties and finally ten singles, one by one, and hands them over to Barbara, the bookkeeper. She tucks the money into the program and laughs. “If we lose more than that, there goes our food money for the week,” she says gaily.

“I am not embarrassed at being well-known. I am only embarrassed at being recognized.”

It is a Sunday in July, the day before the spring-summer season of Hollywood Park racetrack draws to a close. The Grants come to the track often because he is on its board of directors. “I’m used for public relations,” he says, “certainly not for my business acumen”—and because he has always enjoyed the sport. (“People who come to the track are so caught up in making bets they don’t notice fellows like me.”)

Why he enjoys the sport is hard to fathom if you listen to him recite his racetrack tales of woe. Everything got off on the wrong foot in December 1934, when Southern California’s then-only track, Santa Anita, was about to open for business.

“I had an opportunity to invest in Santa Anita,” he recalls, taking off his black-rimmed glasses and replacing them with a tortoiseshell pair. “They were selling shares for $5,000. I, of course, had no belief at all that such an investment could ever pay off.” He smiles wryly. “Hal Roach [the director] had one block left over in the end but I refused to buy it. Well, of course, Santa Anita was a tremendous success. A year later, Roach traded that block for a Lockheed Vega.” Grant laughs. “So now Hollywood Park is set to open and again I’m asked to invest. What do I do? Why, I say, ‘Such an investment could never pay off. Southern California could never support two tracks.’ And, of course, Hollywood Park is a great success.

“Now I am desperate to invest in a racetrack. So they opened one in Las Vegas near where the convention center is today. I begged the fellows who were raising the money to let me put $10,000 into the track, since racetracks were all making money.

“Then one day I was in Las Vegas. A man called Charles Rich had taken over the Dunes, and he said to me that this racetrack, being in Las Vegas, wouldn’t make any money.

I said, ‘Charlie, how can I lose?’

“He said, ‘Look, the people in Vegas, they want action right away. They don’t want to wait thirty minutes between races. Besides, in California there is no other gambling.’

“Well, I go to opening day rather proud of myself for finally getting in on the big score. They are using the Australian tote system, which threw sand on the whole thing. It took them all day to sort out the bets.”

He times a pause just right. “I think the track closed down after about three days.”

He turns to look at Barbara, who is bent over a card making entries. On this day the track is offering $1 million to anybody who picks the winners of all nine races and turns in his card before post time. “Here’s our big chance,” she says to Grant, and keeps on marking.

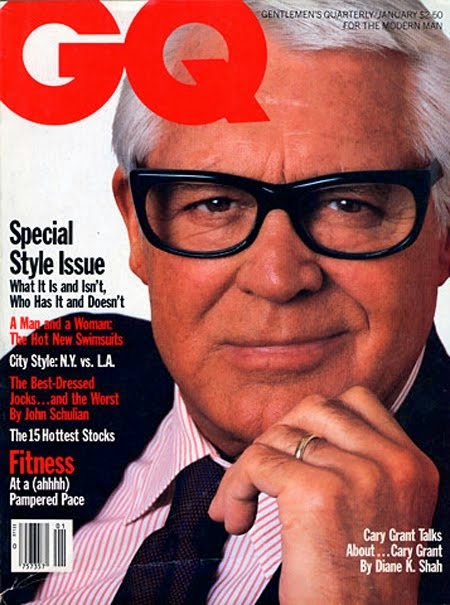

What you want to know, this minute, is what does he look like, really? The answer: Exactly as you might hope he would look.

He does not fill out a card, but the four other people at the table do, and Barbara hurries away to turn the cards in on time. Then she returns to work out the bets for the first race. “What do you think?” she says to her husband.

Grant studies the program and selects a horse named Safety Bank with 8-to-1 odds. “I have my own handicapping system,” he notes, explaining that he bets on jockeys. “First I bet on McCarron, then on Pincay. And then I alternate. Now, this fellow Stevens is also good, so sometimes I bet on him. Does it work? Of course it doesn’t work.”

While Safety Bank is plodding to his fourth-place finish, let us switch our attention to Grant. For what you want to know, this minute, is what does he look like, really? The answer: Exactly as you might hope he would look. The face, compared to the one from the Fifties and Sixties, is a bit rounder, but handsome and startlingly youthful all the same.

He is over six feet tall, still moves with agility and grace, and if there is an extra pound or two around the middle, as he claims, toast a man who will eat what he likes. That he is about to turn 82 is a point he keeps reiterating both out of pride and out of amazement, but where he has hidden the last twenty years is a secret he is not about to reveal.

“You mean you don’t even swim?” asks someone at the table.

“No, no, no,” says Grant, making a face. “I don’t think I do anything.”

“They say that stretching is the best exercise of all,” comes another comment.

Grant nods, stands up and begins rotating his shoulders, then slowly raises his legs, one at a time, behind him, as the conversation continues. Suddenly, he stops. “I don’t think I’ll stretch anymore,” he says with a foolish grin. “I just kicked that lady.”

“Who do you like in the second race?” says Barbara, whose horse in the first race, Saloum, came in first. Grant picks Gary Stevens’s mount, Free World, to win, and one called Built To Last to place. Neither horse finishes remotely in the money.

One remarkable thing about Grant is that for a man of his fame he is so cheerfully available to people who encounter him.

A man walks by, marvels at Grant’s appearance and tells him, “Whatever you’re doing, it agrees with you.”

“Losing,” says Grant.

One remarkable thing about Grant is that for a man of his fame he is so cheerfully available to people who encounter him. When he comes to the track he moves about the VIP Director’s Room at will, happily chatting with everyone. By comparison, other regulars such as Roger Moore and Michael Caine sit glued to their tables making it quite clear that they are not to be bothered by strangers who happen by.

Not that Grant seeks the limelight.

“I was at Dodger Stadium last night sitting in Peter’s box,” he says, referring to Dodgers owner Peter O’Malley, “when I spotted some people I knew down below. I started down, but I never got there. I began to attract so much attention. It was like throwing bread to the pigeons.”

Yet when he is asked what it has been like to be that man feeding the pigeons for so many years, Grant is silent for a moment. Then he says, “I don’t feel awed by it a bit, because it’s always been part of my life. I honestly don’t know what life is like without it. I am not embarrassed at being well-known. I am only embarrassed at being recognized.”

For the third race, Grant puts his money on a Pincay mount, Relaunch A Tune. “Five dollars,” he tells Barbara. “I’m showing off.

“When I was insecure I used to throw money around to impress people,” he adds. “But then I learned you don’t impress people like that. So I became a tightwad, or so people said. When you’re a star, you’re either a tightwad or a homosexual. I’ve been accused of both.”

His horse comes in first.

Barbara nudges him. “For the seventh race, we’re going to bet this one on your behalf,” she says, pointing to a name in her program, “Lord Of The Wind.”

“I think I’m more Duke Of The Wind,” says Grant agreeably.

They were married in 1981, after having met in London in 1976 at the Royal Lancaster Hotel. Grant was there to attend a meeting for Faberge, whose board he sits on. Barbara, some forty-seven years younger than Grant, was living in London and doing public-relations work for the hotel.

“Yes,” says Grant, “I saw a great deal of Barbara then. From ten-thirty in the morning till eleven.”

“When you were freeloading,” she adds.

“I just noticed this beautiful gal roaming around. She tried to avoid me.”

“That’s not true,” she insists.

“The first time I saw you…”

“I raced off to see Margaux Hemingway’s press conference.”

“Yes, I was upstairs…”

“No. You were downstairs at the bar.”

“Was I?”

Barbara is asked what her first impression was of Grant. She toys with her napkin. He waits expectantly. She says, “Since this story isn’t about me, I don’t think it’s an appropriate question.”

“Aw, come on,” says Grant. “I want to know. What did you think of me? I’ll tell you what I thought of you. I thought you were quite a dish.”

She smiles. He smiles. And that is the end of that.

Later she says, “Darling, did you notice? Lord Of The Wind came from behind.”

Part II: An Evening with Cary Grant

Again we are on the phone. Cary Grant is saying, “One night a fellow stood up and said, ‘Mr. Grant, why aren’t there more Westerns, we would like to have more Westerns.’ And I said, ‘Well, OK, I’ll spread the word.’ Twenty minutes later another fellow stands up and says, ‘Why don’t we have Westerns?’ I said, ‘What’s your name?’ He said Mr. So-and-So. And I said, ‘Why don’t you two talk to each other?’ So they did. After a while, I said, ‘Do you mind if I lie down?’”

Grant is talking about the auditorium performances he puts on several times a year. He accepts some offers, rejects most and says he isn’t quite sure why he does them at all. When asked this very question at “an evening” a few nights before, Grant told the audience, “Good question!” And they laughed.

He is a shrewd fellow, nonetheless. Now, over the phone, he is saying that Barbara Walters called and wanted to know if he would do “an evening”-type performance on her show. He says he turned her down. “Why do it on TV?” he says. “I get paid separately for each of these things.” As to how much, he says: “None of your damn business ….No, I’ll tell you. It depends on the size of the auditorium, the ability of the people to pay and how much of it goes to charity.”

His acceptances are generally for performances in parts of the country he would like to visit. Each evening comes with his ironclad dicta. For his latest performance, at the Claremont Colleges outside Los Angeles, Grant stipulated no advertising, no interviews, no fan mail. No tape recorders and no cameras. Perhaps a few sandwiches.

There is no one more delightful than Cary Grant performing, even at this ripe old age he keeps harping about. Seated on a high stool on the bare stage, he looks as if he has stepped off the screen from one of his movies, like the character in Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo who just walked off the screen and landed in real life.

In fact, the final shot of the introductory montage of Cary Grant film clips is of Grant, ever so large on the screen, walking onto a stage, while below, the live article, dressed in an elegant gray suit and crisp white shirt, is walking onto the auditorium stage. The 2,483 people who have driven through a downpour to see him leap to their feet and applaud him.

“Thank you very much, thank you. I haven’t the vaguest idea how to start.” Pause. “If you feel like asking questions, shoot. If not, we’ll all dance.”

(A woman): “Mr. Grant, all of us in this room cannot believe we’re really here with you … we’re so excited.”

“Thank you. But how do you know they’re so excited?”

(Continuing): “I would like to ask you what was the most memorable moment in your whole spectacular, wonderful life, including a woman if you like.”

“Well, actually it does. It includes my mother … the day I was born.”

(Another woman): “I was wondering what your daughter Jennifer thinks of your films?”

“Well, I can tell you this. If she sees my films, she’s staying up too late. But she seems to like me, we enjoy each other’s company. I think I took her to see Bringing Up Baby; I ran it up specially at MGM somehow. She was 14, perhaps. She didn’t like it at all. She pretended to, of course.”

(A man): “Mr. Grant, you’re a hell of a guy. On those film clips they showed you doing backflips. Was that actually you?”

“Yes, yes.”

“Then you’re even more a hell of a guy.”

(Another man): “Would you ever come out of retirement?”

“No, no. When I was a young man, I saw an actor I regarded so highly, a very big star in the silent movies. And when I saw him years later in a film, I was so disappointed. He was not the same man. He was the same man but, my goodness, he didn’t look like the same man. I was very disappointed that he had aged, or was aging.”

Grant did in fact come out of retirement once. It was in the early Fifties. He was married then to Betsy Drake, his third wife. (The five, in order, are actress Virginia Cherrill; heiress Barbara Hutton; Drake; Dyan Cannon, the mother of his only child Jennifer, now a junior at Stanford; and Barbara Harris.) Grant decided to make no more pictures and set off on an around-the-world tour.

“I was in the Orient,” he would later relate, “when I got a wire from Hitch saying, ‘Come back. I’ve got this wonderful new actress.’ Well, if Hitch had said I’m going to make a movie of the telephone book, I’d be there. So I came back. He said, ‘I have this new girl, and she’s terrific.’

“‘Who’s that?’ I said.

“‘Grace Kelly.’

“Well, I was delighted, because I had seen her in a small role and I was very impressed. We made To Catch A Thief, and she was the best actress I ever worked with, with all due respect to Ingrid. But Grace, she was really there in a scene. She really listened. Unlike most actresses, she wasn’t worried how she looked or what angle the camera was shooting her from. So if I changed a bit of dialogue, she went right along. Then she had the indecency to marry Rainier. And that was the end of that.”

Now, at Claremont, Grant tells why he retired in 1966 for good. “You start worrying, ‘Is my double chin showing?’ There comes a time when you have to give it up.”

(A woman): “Mr. Grant, which role that you played comes the closest to the real you?”

“The bum I played in Father Goose.”

Part III: On the Phone Again

“Now, what else would you like to know?”

“About the LSD.”

“But that is so old, it’s all been said.”

“I’m curious. It was a very long time ago, wasn’t it?”

“Yes, twenty-five, thirty years ago.”

“How often did you go?”

“Every week, for a hundred sessions. We had a small group; it was with a doctor in L.A. Each of us went separately, of course, and it was monitored. The dosages were small. But unfortunately, LSD was known as a drug, and drugs have a bad connotation. It connotes heroin. When, in fact, to come down, you had to take a drug, you had to take a cigarette.”

“How did it work?”

“I laid down on a couch. The doctor read a book over in the corner with a little light. He played music associated with my youth. Like Rachmaninoff. It would last three or four hours.”

“What would happen?”

“You would see nightmares, your fears, the scenes associated with nightmares.”

“What came out of these sessions?”

“I learned to forgive my parents for what they didn’t know. And my fear of knives. If I see a sharp knife, I cringe.”

“Why is that?”

“I know where that came from, but I won’t tell you.”

“And so now the demons are gone, you are at peace?”

I was amazed. In all my years of reporting, nobody has ever called up after an interview to suggest that maybe it had not gone as intended, not ever.

“You join humanity as best you can. I like myself as far as I’ve gone, though I do wish my vocabulary were better. Otherwise, I think I’m a fairly decent fellow. I no longer have hypocrisies.” Then, to someone else, “Is John going out today? I wanted him to get my dinner coat.”

“Sorry, where were we? Oh yes, hypocrisies. You know, it’s interesting. You can tell how secure a woman is by the amount of makeup she wears, did you ever notice? … Ingrid would wear no makeup and have a shoelace tied in her hair. She was exactly herself, no artifice whatsoever. She had no knowledge about fashion or such matters. She just showed up and did her work. Women who wear all that makeup, there’s some faking going on.”

He pauses. “That’s why I had trouble with Mae West. I never knew who she was.”

Part IV: A Luncheon with Cary Grant

The reporting was finished; it was two weeks after the day at the track when I found this message on my telephone-answering machine: “Hello, this is the fellow you were with at the racetrack. Please call me at your convenience.”

So I rang him up. “Now look,” he said, “it seems to me that you might not have gotten everything you needed that day at the track. You were preoccupied, a love problem perhaps. Or maybe I was just a terrible bore. But somehow you were not there. So if you still have some questions and maybe you don’t, we can continue, if you like.”

I was amazed. In all my years of reporting, nobody has ever called up after an interview to suggest that maybe it had not gone as intended, not ever. And, though I was not aware of being preoccupied with any love problem, the truth is we had not connected that day at the track the way we always had on the phone. And he had sensed that, Cary Grant had.

Please, God, don’t let me spill anything … just this once.

So, on a bright, beautiful Tuesday, I set off, fearing that I would not find his house despite his carefully spoken directions, for … my mother should only forgive me, lunch with Cary Grant. Preoccupied this time for sure. Thinking, please, God, don’t let me spill anything … just this once.

The house is just the sort you might imagine Cary Grant would live in. It sits atop a hill overlooking Beverly Hills, overlooking the sixteen-acre estate of Harold Lloyd, much of it carved up by developers, overlooking Century City to the south of that. To the east are the skyscrapers of downtown Los Angeles. To the west, on a clear day, one can see past Westwood, past Bel Air, past Santa Monica, past fifteen miles to the Pacific Ocean.

Halfway up the drive stands an electric gate. I speak my name into a small box on a pole and the gate swings open. I drive round the house to an enormous parking area and slowly walk back to the front door. Grant is standing there, a vision in white.

He is wearing a long-sleeved white shirt, the tails out, white cotton slacks and the kind of snowy-white socks seen only in detergent commercials; no shoes. There is a gold chain around his neck, a thin gold wedding band on his finger.

“We are alone today,” he says, explaining how the help is away and Barbara is away. “But she left us some lunch. I hope it will be okay.”

Barbara Grant, who has taken on the chairmanship of a charity ball for the Princess Grace Foundation, a job that has turned into a twenty-six-hour-a-day marathon has, before dashing off to some meeting or other, left the kind of lunch that would have taken me a month to prepare—after a six-week crash course at the Cordon Bleu. Barbara Grant, while we’re still on the subject, organizes all of her husband’s appointments, handicaps horses and, knowing his preference for wearing caftans around the house in the evenings, once sewed him a whole closetful.

The dining area is out of House & Garden. A large white oval table on hidden casters (for easy moving, Grant proudly points out) overwhelms an alcove, one of whose sides is a wall of large windows. Under the windows is a banquette with bright-green cushions that match the lawn outside. The place mats and napkins are yellow linen. There are bowls of flowers and fruit; tall Lucite pitchers of water and orange juice.

“I deplore the times I haven’t been polite,” he muses. “But you just can’t be a normal person.”

From a kitchen the size of the QE2, we fetch the platters. There is a cold quiche that Craig Claiborne should review, all manner of pates and cheeses, a salad, warm bread and for dessert, a perfect banana-cream pie.

We sit at the table looking out a wall of windows from which can be glimpsed the terrace, the lawn and, down the hill, the pool. I bite into the bread and await Hitchcock to come out screaming and throw me off the set.

Years ago, when Grant was filming in New York, he would stay at the Plaza hotel and have dinner in the famed Oak Room. “I would sit in the George M. Cohan booth, right next to the door [the same booth in the opening sequence of North by Northwest],” he says. “There were two huge pillars that hid me and my date. Actually, they hid me better when I was alone, which was good. Since I didn’t have a date.”

This came up in connection with Grant’s recitation of the measures he had to take to avoid being mobbed. “I deplore the times I haven’t been polite,” he muses. “But you just can’t be a normal person.”

Over the years, he has mastered some techniques to turn intruders away. “I’ll be having dinner and a man will appear with a pen and paper and say, ‘I hate to do this but….’ And I’ll say, ‘Oh, don’t do anything you hate! That’s terrible.’ Or sometimes the poor fellow will be so flustered, he’ll say, ‘You know, you’re my greatest fan.’ And I’ll say, ‘Well, I don’t know how long I will be!’”

“I think of life as a series of plateaus. And since I hope to be on a better plateau, I can’t say I’m completely satisfied. Do you see? Or have I ruined your lunch?”

It was not this kind of fame that attracted him to acting. Growing up in Bristol, England, he had been fascinated by the big steamships and schooners that moved in and out of the city’s port. “I hung around the wharves hoping to get a job as a cabin boy,” he says. “I couldn’t be a travelling salesman, I was too young to be a commercial traveler. I was too young to join the army. But all I dreamed of was to travel.”

He made friends with an electrician at a local theater. He was fascinated with the lighting tricks and a brand-new telephone switchboard. “And then I noticed actors in the cast of these vaudeville shows who were as young as I am,” he recalls. “I thought, ‘My God, actors travel.’”

“Have you ever wondered how your life would have gone had you not wanted to travel?” I ask him now.

And he says, “I think we all find ourselves where we put ourselves. We choose our places. I don’t believe in fate. I don’t believe in good luck, only good luck in the point of birth.”

“Is there anything along the way you might have wished to change?” I ask.

“Some people are totally at peace,” Grant replies, “but they are dead, of course. I think of life as a series of plateaus. And since I hope to be on a better plateau, I can’t say I’m completely satisfied. Do you see? Or have I ruined your lunch?”

Over dessert, he singles out one of the negatives of Hollywood stardom: the malicious gossip to bring him down.

“I had a valet once,” he recalls. “I was married to Barbara Hutton at the time and he told some reporter what a skinflint I was. Said I never picked up a dinner check. Now, how would he know that, since he never dined with us? The fact is, I didn’t pick up dinner checks. It was arranged so that they were automatically sent to my house. He also said I was so cheap I cut the buttons off my old shirts before throwing them away. Well, why not? They were very good buttons and it was nice to have them if I lost ones off my good shirts.”

He pauses. “Any guy out front is always a target. You know, in the wars, the commander would be the first one out of the trenches and it was not unusual for one of his own men to shoot him in the back. It’s the very fact of him that puts others in an inferior position.”

He sips his orange juice. “The trick in life is not to feel inferior and not to feel superior. There is always another guy who knows more than you and you must recognize that.”

“Do you ever feel inferior?” Grant grins. “I never learned to play the cello,” he says.

Part V: That Certain Style

Again the reporting is finished, again there is a phone call.

“Perhaps we ought to talk about clothes, for this magazine, don’t you think?” Again I am amazed.

Cary Grant—Mr. Elegance, Mr. Style, the matinee idol of seventy-two films, the example for whom Mr. Webster coined the word “debonair”—has so far refused to discuss the subject of style, brushing it off, saying, “Oh, I don’t know,” shifting to another topic.

Part of his style derives from his manner: the easy self-effacement, the cheerful good humor. There is a wonderful story about Grant, from several years ago, when he was asked to participate in a variety show at Jennifer’s school. Onto the stage he came, with a brown paper bag over his head, everyone wondering, Who is that? And then he uttered his most oft-quoted (but never really spoken) line, “Judy, Judy, Judy.” Bringing down the house.

There is also the matter of clothes.

He has built electric closets in his dressing room at home that pop open at the simple touch of a hidden button—all to stymie burglars. He is quite proud of the setup, or was, until a severe thunderstorm knocked out power lines in parts of L.A. three years ago. “Can you imagine,” he told an acquaintance over the phone, “I haven’t been able to change my clothes for three days.”

Discussing clothes seems to be as far as Cary Grant will go on the subject of style.

“In the movies,” he says, “all men paid for their own wardrobes, did you know that? So, of course, I would have to wear my own suits. Occasionally, I’d have to buy six of the same suit and a dozen ties, depending upon the scene. I had a tailor in Hong Kong who learned from the English cutting book. The English cut the armholes higher, whereas in America they cut them lower to fit more people. Once, I had a director who complained my suit didn’t fall right across the back. I said, ‘But I’m not going to turn my back to the camera, are you crazy?’”

In addition to supplying his own wardrobe for films, he often took an interest in what his leading lady would wear.

“I saw girl after girl wearing clothes that a real girl, in the same circumstances, could never afford,” he says. “When I made That Touch of Mink with Doris Day, I took her to certain fashion houses that I knew had the type of dress a girl could afford. Remember, she played a secretary. I took her to Anne Klein, who had a range of clothes, very reasonable. But there was a deeper reason. Not only did girls wear clothes beyond their means, they often cost the studio too much.”

And you had a piece of some of those pictures?

“Yes.”

Grant’s father worked as a presser for a clothier in Bristol, and it was from Elias Leach that young Archibald got his best advice.

“I’ve always fancied shoes,” he says, “and my father told me, ‘If you can’t afford good shoes, don’t buy any. If you can afford one pair, buy black. If two pair, one black, one brown. But they must be good. That way even if they are old, they will always be seen to be good shoes.’”

He also, he says, had a penchant for jazzy-looking suits, “elegant sorts of tweeds and glenurquhart plaids. My father said, ‘Don’t buy them unless you can afford a lot of suits. Otherwise, people will say, “Here comes that suit down the road,” rather than Archie,’” he laughs, “which is me.”

His all-time favorite garment is the now-defunct Nehru jacket. “So comfortable, so practical,” he sighs. “But, of course, the fashion industry would never allow them to stay. With a Nehru jacket a man didn’t need a tie or a shirt or a jacket or cuff links, so a lot of money would be lost. Before I ever got around to buying one, they were gone.”

One fashion tip Grant says he’s picked up over the years is that powerful men, men like Aristotle Onassis and Lew Wasserman and D.K. Ludwig and Bunker Hunt, “those characters always wore dark-blue suits.”

“But you wear a lot of gray,” I put in.

“I’ll tell you a little secret,” he says. And I wait for him to say how gray flatters white hair. Only that is not what Cary Grant says.

What Cary Grant says is, “If your hair falls out a bit, nobody will notice.”