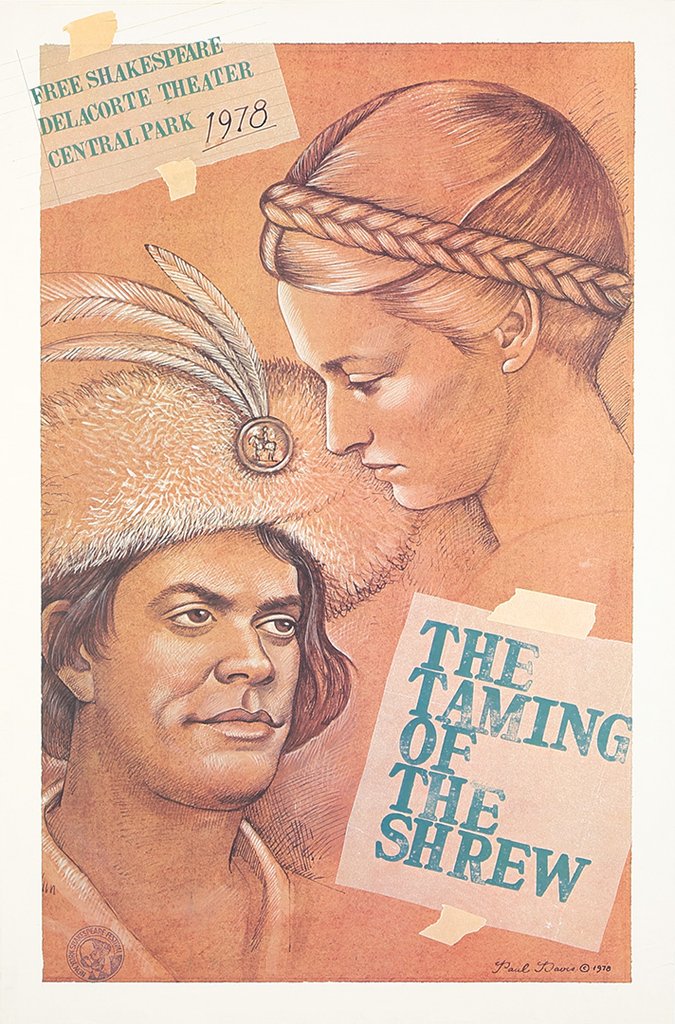

Meryl Streep and Raul Julia are rehearsing The Taming of the Shrew seated on two studio chairs in a rehearsal room at Joseph Papp’s Public Theater. Act II, Scene 1, when Kate and Petruchio meet and clash for the first time. Miss Streen has Kate’s skirts hiked up—revealing two red kneepads she’s wearing for protection—and the Puerto‐Rican born Mr. Julia is blowing away Petruchio’s lines like so many dandelion seeds. “She swings as sweetly as the nightingale,” he says. Then stops.

“Jesu Cristo!” Several other Spanish oaths. Then up out of his chair. “Sings!” he beats it into his brow, with both hands, “She sings as sweetly as the nightingale!” But Miss Streep is already clowning as Kate the Swinger. Her fingers snap, her shoulders sway, Dutch blonde hair whips, hips do their thing. She never leaves her chair.

It’s Mr. Julia who takes a walk. All the way around a black pillar in the Old Prop Room of the Public Theater, still holding his head, then into a furious flamenco stamp on his way back. If Miss Streep can break everyone up with her improvisations, Mr. Julia’s lithe movements might raise an envious eyebrow from John Travolta.

The result of these preparations, by the way, is now on view nightly through Sept.3 at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park. But back to the rehearsal.

It’s a treat just to watch Mr. Julia struggle with a fluff. He knows Shakespeare, that’s not his problem. He read the plays back in Puerto Rico. But his rhythm is not that of Elizabethan rhetoric. He has a Latin cadence that may say something about why they call English blank verse … blank. When he pulls it all together, making the words fit the reggae, what audiences get from Raul Julia—at 37, commonly acknowledged one of the best actors in Joseph Papp’s stable—is an upended, zealous, but oddly classical reinterpretation.

Take his Osric a few years back, also for the New York Shakespeare Festival in the Park. Osric is supposed to come off “a waterfly.” But Mr. Julia managed to play him so princely that he put down Hamlet. The Times’s critic wrote he had never seen “such a coolly stylish Osric … so much grace, passion, and venom.” Last season Mr. Julia did the reverse with the loutish Lopakhin in The Cherry Orchard, crashing him into the Chekovian furniture like runaway peasant trundle. Earlier he was an unmatched Macheath in Threepenny Opera, a Charley far removed from Ray Bolger’s in a revival of Charley’s Aunt, and a most protean Proteus in his first success, Two Gentlemen of Verona. Now it’s Petruchio, usually played for all the macho highjinks the comedy can stand. Not by Raul Julia. “I see Petruchio as a real alert guy. Period. Alert enough to move from the greedy calculation that ‘This woman is loaded …’ to ‘Wow, she’s incredible.’”

That’s a pretty upbeat interpretation of a play that is usually staged as a pitched battle of the sexes, with the score often Petruchio: 100, Kate: 9. Five acts of farce, bawdry and knockabout, with Petruchio—“come to wive it wealthily in Padua” freezing, starving and otherwise abusing Kate into conjugal submission. But in the New York Shakespeare Festival’s production, Mr. Julia’s Petruchio is taken altogether a different way by Kate the Cursed.

The director expects a round of hissing each night.

“She’s not what Petruchio expected,” Mr. Julia argues. “This is for me, Petruchio says. I’m for you, he tells her, and that’s how it’s going to be. ‘By this light …’ and that’s not the sun, that’s here.” He taps himself, strong right forefinger, between, those big brown eyes that he can roll all the way to the last row. “‘… whereby I see your beauty.’ He sees she is a beautiful human being.”

So what Raul Julia brings to the Park this week is Petruchio in love. “Not the big man macho and the poor helpless little shrew, but two people getting it together, down to where they really want to be.”

That’s when Shakespeare, during this rehearsal, begins to pick up a strange calypso. “‘How tame when men and women are alone,’” Mr. Julia tries the line, “ ‘a mea … a meacock … a mea’” “ Little hang‐up here word means “meek” — got it! “ … a meacock wretch can make the curstest shrew. Give me your hand, Kate….’”

And very daintily, still without leaving her chair, Miss Streep hands him her left foot.

That’s Meryl Streep. That’s her all over. One of the fastest‐rising actresses in the country, she is a quick‐study comedienne who played seven roles her first season in New York, in 1976, and nearly won a Tony as the butt‐sprung, puddin’‐breasted cracker floozie in an off‐Broadway revival of Tennessee Williams’ Twenty‐Seven Wagons Full of Cotton. Today, only three years out of Yale Drama School, she seems Mr. Julia’s rightful leading lady. Especially as wild Kate, not like, never to be like, other household Kates.

They’d been in one play together The Cherry Orchard—but hardly opposite. As Lopakhin, Mr. Julia watched, off stage, while Miss Streep did one of her more amusing pratfalls as the maid Dunyasha. Miss Buster Keaton. She has also played, from Yale on forward, such grotesques as Constance Garnett, cobwebbed, in a wheelchair, attended by Ernest Hemingway, for The Idiot’s Karamasov (in which she conjugated the Russian verb karamasov), and the Salvation Army’s song‐belting Lieutenant “Hallelujah Lii” Holiday in the Brecht‐Weill musical Happy End.

Mr. Julia gets a taste of Miss Streep’s comic grape during rehearsal when the stage direction says “She strikes him.” First she comes at him with a backhand slap to the chops. Next an upper‐cut from the floor. Then a hard knee to the groin, one red kneecap flashing. And she does it all, again, without leaving her chair—luckily only warning him, “You’ll never know where it’s coming from.”

Only she doesn’t, can’t, won’t play all that farcically. She won’t let the relationship — yes, she’s into the love story, too— lose that much.

“What I’m saying is, I’ll do anything for this man,” Miss Streep argues.

“Feminists tend to see this play as one‐way ticket for the man, but Petruchio really gives a great deal,” she insists. “It’s a vile distortion of the play to ever have him striking her. Shakespeare doesn’t do it, so why impose it? This is not a Sado/Masochist show. What Petruchio does is bring a sense of verve and love to somebody who is mean and angry. He’s one of those Shakespearean men who walks in from another town. They always know more, see through things. He helps her take all that passion and put it in a more lovely place.”

Meryl Streep is talking that way because, as she admits, “I’ve learned something about that. If you’re really giving, you’re totally fulfilled.” What happened to her, on her rise from ingenue to leading lady—is she fell in love with another of Joseph Papp’s actors named John Cazale, who died of cancer this year. The poignancy of the affair comes right home when she recalls how she moved into the hospital just before the end and “read the sports page to John in Warner Wolfe accents to his dying day.”

John Cazale was Alfredo in The Godfather, the weakling brother whom Al Pacino finally had shot. But Mr. Cazale was much more, a versatile character actor who played the lustful puritan Angelo to Meryl Streep’s virgin Isabella in the New York Shakespeare Festival’s Measure for Measure two seasons ago. That’s when they discovered each other, in their own kind of Kate/ Petruchio thing.

“The jerk made everything mean something,” she says. “Such good judgment, such uncluttered thought. For me particularly, who is moored to all sorts of human weaknesses. ‘You don’t need this,’ he’d say, ‘you don’t need that.’ Kind of like Petruchio: What’s right stands alone.”

Mr. Cazale made his last movie with Miss Streep—The Deer Hunter, which will be released this fall—during a period of remission. Even so, Universal Studios tried to dump him because his life was uninsurable for the period of shooting. The director lied and kept him on location. In the movie, as always, she says, “What he did was funny, but it breaks your heart.” Then she went off to Vienna to play Frau Weiss in Holocaust, expecting Mr. Cazale to join her. He couldn’t, and she spent the last three weeks of shooting counting the sleepless hours till morning under “that damn eiderdown.” When she got back to New York, Mr. Cazale was limping from bone cancer.

That is why, Miss Streep says, she doesn’t have any trouble with what nowadays seems the biggest problem with The Shrew: Kate’s final speech. Serve, love and obey, “and place your hands below your husband’s foot.”

“What I’m saying is, I’ll do anything for this man,” Miss Streep argues. “Look, would there be any hangup this were a mother talking about her son? So why is selflessness here wrong? Service is the only thing that’s important about love. Everybody is worrying about ‘losing yourself’—all this narcissism. Duty. We can’t stand that idea now either. It has the real ugly slave‐driving connotation. But duty might be a suit of armor you put on to fight for your love.”

That may not sound like any prior Kate—even Kate Conformable, as Shakespeare finally has her—and with three States yet to ratify, director Willford Leach fully expects a round of hissing every night in the Delacorte Theater from all those backing the Equal Rights Amendment. “I don’t think the last speech jumps out of nowhere,” Miss Streep still insists. “It’s the logical emotional end.”

One of those more than sticking by her on this is Raul Julia. In fact, even though he “grew up with all that stuff” that traditionally moves Petruchio, he is ready to go even Shakespeare one better. He could give Kate’s speech as Petruchio.

“I could say the same thing about my duty to her. Maybe it was more appropriate to give that speech to women in Shakespeare’s time. But I can see it being done that way someday. Kate gets up and says, ‘Petruchio, tell these men what duty they do owe their wives’ And I would get up and do it myself.”

Miss Streep, still seated in her chair, hands him her right foot. This time he kisses it.