The face is a harbormaster’s face, or a potato farmer’s, or a lobsterman’s: sharp, prominent nose, articulate features, eyes meant for pinpointing danger. At 39, the body is aching but supple. As he enters the sepulchral clubhouse of the Boston Red Sox moments after their agonizing loss to the New York Yankees in the season-ending tie-breaker game, Carl Yastrzemski tokes hard on a Marlboro and sips from a paper cup of beer.

This afternoon, he made the last out of the season. It hurts to make the last out of a pickup whiffleball game at a picnic; this last out may have ended Yastrzemski’s fondest dream. The one-game shoot-out came down to one pitch, and Yastrzemski lost. Now he stands red-eyed in a crowd of oddly silent reporters. Around him, the other players—knowing the season is over—still don’t want to shower and change. They sit motionless in their uniforms, some crying, some immobile with grief.

First baseman George Scott sits at his locker, packing his bats into a duffel bag. A sportswriter approaches with a timeworn question: “George, is it going to be a long winter for you, looking back at what might have been?”

Scott is a huge, warm-hearted man, but he’s been pushed to the edge of his gentleness. “Long winter?” he says. “I figure it’ll go like November, December, January, ‘less they puttin’ some new months on the calendar they ain’t told me about. Be about as long as ev’y otha winter. What kinda fool question is that?”

Across the room, pitcher Bill Lee shakes his head. “If the fans could’ve held off yelling, ‘Yankees suck,’ just one more inning, I think we might’ve won it.”

Yastrzemski drags on his cigarette and then clears his throat. As he stands in the heat of the TV lights, the streaks of shoe polish under his eyes—painted there to cut the glare of the afternoon sun—begin to melt. His whole speech is a fight against tears.

“My insides are a bunch of knots. Defeat is heartbreaking, there’s no way around it.” He stares at the ceiling, then sighs explosively. “In a couple of weeks I guess I’ll work it out. Right now I’m still numb.

“This year we had three months of joy, one month of frustration and then a great comeback, and then… I’ll just remember the last week of the season—knowing you could not lose one game, and not losing.” A few minutes later he succumbs and cries softly.

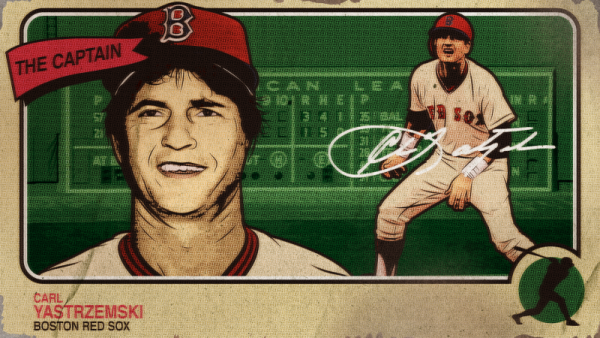

At 39, most ballplayers are warming the bench, coaching third base or opening bars called The Bat ’n’ Glove. But in the late summer of 1978, Carl Yastrzemski, the team captain, sparked the Red Sox with key hits and miraculous catches, in open defiance of nature.

“He wants to win so much, the captain,” said Jerry Remy, Boston’s gifted second baseman. “More than any of us.” Remy uses the term “captain” with reverence, as do many of the younger players, who see themselves as first mates to Yastrzemski. “You know how you pretend you’re a major league star when you’re a kid, playing stickball in the street?” Remy said. “Yaz hit .450 on my street one year—every time I swung, it was for him, so he got a lot of hits. And now I’m two lockers away from him.”

The captain’s dream is to win the World Series, and his desire is fueled by past frustrations. Twice in his career, in 1967 and 1975, he led the Sox into the last game of the Series, and twice he lost.

Near the end of this season, he was asked about reports that he’s obsessed with the championship. His silence was so long it seemed he would never answer. He flicked ashes from this thermal underwear, studied his uniform and finally spoke.

“Playing this long, you’d like to be able to say ‘I played on a World Champion once.’ After it’s over. Just once… All my All-Star rings have been given away, passed on to friends and relatives. But that’s one ring I’d keep.” Thirty seconds later, still peering into his locker, he added quietly: “Yeah, I’d keep that one.”

“Yaz reminds me of John Wesley Hardin, the outlaw,” says Ken Harrelson.

For most of the year, it seemed he would get one. With slugger Jim Rice powering home runs out of tiny Fenway Park, Yastrzemski hitting at a .300 clip and the whole team playing impeccable defense, the Red Sox built a 14-game lead over the seemingly neurasthenic Yankees. And then, in late August, came the slump.

The Slump. One of the most awesome nose dives in sports history. For nearly a month, the Red Sox resembled a municipal softball team well into its third keg of draft. They stranded runners, threw balls into the stands and dropped pop flies—playing, as Yastrzemski reportedly told them, “like horseshit.”

At the nadir of their season, he called a rare team meeting. “I kept it short and simple,” he recalls. “I said, ‘We’ve had some injuries, but let’s play our best and not alibi. If we’re gonna go down, let’s go down with class.’ ”

Yastrzemski is plain-spoken by nature, but eloquent in gesture. He showed what he meant by “going down with class” in a play he made against the Yankees during the slump. Late in one game, with the Sox hopelessly behind, he raced into the left-field corner for a line drive. He dove full length, skidding ten feet on his belly, and made the catch where others might have just played it safe—all this while suffering from muscle spasms in his lower back. One does not throw a pain-wracked 39-year-old body headfirst into the dirt with impunity. But the agony could be tolerated; abject surrender could not.

Perhaps inspired by Yastrzemski’s heroics, the Red Sox soon began to win again. They whittled down the Yankee lead from three and a half games to one. In the last week of the season, they were suddenly back in a pennant race, and Yastrzemski had one more shot at a World Series ring.

Yastrzemski’s season didn’t produce the dazzling statistics of his youth: In 1967, for example, he won the Triple Crown—one of the game’s rarest achievements—by leading the league in home runs (44) batting average (.326) and runs batted in (121). In 1977, he played the entire season without making a single error in left field, and six times in his career he has hit better than 300.

In 1978, he finished at .277, with 17 home runs. But he led the league in what baseball observers are wont to call “the intangibles.” In a way that transcends statistics, Yastrzemski had his most memorable season. As Toronto pitcher Tom Murphy says, “The wonderful thing about Yaz is that he’s thirty-nine going on twelve. And forget statistics—most pitchers will tell you that Carl is still the greatest clutch hitter in the league.”

More than other games, baseball gives its players space—both physical and emotional—in which to define themselves. Oddly enough, in his years of stunning numbers, Yaz remained enigmatic, accused by some fans of not caring enough. But this year, as he played against pain, frustration, the Yankees and his own age, Yastrzemski was something to watch. Long after he retires, the enduring image of Yaz will be the Indian Summer he enjoyed in the pennant race of 1978.

The Sox are playing the Detroit Tigers tonight, with five days left in the season and the Yankees still a game ahead. There are squalls in the Atlantic, and the stormy air whips the centerfield flag. Yaz stands in left, in the small green port that is Fenway Park, at the station that’s been his for 18 years. In the ninth inning, with the tying run on base for Detroit, he races in to make a tumbling catch of a dying line drive. Somersaulting to his feet, he holds the ball aloft, as if he’s retrieved it from deep water. The Red Sox hang on to win, 5 to 2.

But inside the Boston clubhouse, the players feel sore and impotent. They are winning, but so are the Yankees, and the Sox sense the pennant slipping away. It’s like a man scrabbling at a tenth-story window ledge: The horror is not so much that he falls as that he almost doesn’t.

“You the old man on this club,” says Tiant.

“Bullshit,” Yaz says. “Your birth certificate is a joke—it may say you’re thirty-seven, but you’re fifty. Who checked those records back in Cuba in the twenties?”

Bill Lee spins the radio dial until he finds an appropriate song, Warren Zevon’s “Lawyers, Guns and Money.” “That says it,” Lee observes, singing along: “Send lawyers, guns and money/Dad, get me out of this.” The players shower and dress quietly. The next song on the radio is Bonnie Bramlett’s version of “Can’t Find My Way Home.”

Yastrzemski sits in front of his locker, inhaling a cigarette, despite severe bronchitis. (His chain-smoking is a trade-off—nicotine for hysteria.) Though the spasms in his back—which until recently forced him to play in a corset—have subsided a little, he’s enduring pain that would put younger men in bed. To ease his tension, he enters a razzing contest with pitcher Luis Tiant on the subject of old age.

“You the old man on this club,” says Tiant, in a heavy Cuban accent.

“Bullshit,” Yaz says. “Your birth certificate is a joke—it may say you’re thirty-seven, but you’re fifty. Who checked those records back in Cuba in the twenties?”

“Hey, Yaz, I be pitcheen for ten year while you are sitteen aroun’ with you grancheeldren. I send you a postcard, let you know what’s goeen on.”

“Ten years? You’ll be senile by spring training. Look in the mirror, Luis. You’re old.”

“Looks don’ matter,” Tiant says. “Look at Bob Stanley. He only twenty-three, but he so ugly he look ninety.”

Yaz’s face splits in a craggy grin. The clubhouse is a feast of dialects—Ozark twangs, wide Latin vowels, Southern drawls and mumbles. Yaz talks in nasal, staccato bursts that hint vaguely of his Long Island origins.

“This joking is a good sign,” he says, as two infielders cackle over a copy of Hustler. “It was quiet in here when we were losing. We started trying too hard, playing out of desperation. There’s a fine line between being keyed up and desperate. That’s where I want to be.”

And that’s where he is. After years of playing in a high mania—he would bust up clubhouses, shatter bats, cover home plate with dirt to protest a called strike—he’s now steady enough to be captain.

“Yaz reminds me of John Wesley Hardin, the outlaw,” says Ken Harrelson, a Red Sox broadcaster and former teammate of Yastrzemski’s. “Wes Hardin was a quiet man, the most feared gunman because of his great cool—he’d never draw wild, but he was known as the quickest. See, Yaz is the dead opposite of most people. He’s uptight until the moment of crisis, until something extreme must be done, then he lowers his metabolism.”

The next day, Yastrzemski spends the afternoon at New England Rehabilitation Center, receiving treatments for his bronchitis—“They put this mask on my face and shoot a mist down my throat.” The treatments, intended to keep the bronchitis from worsening into pneumonia, last three hours. Second baseman Jerry Remy, who clearly idolizes Yaz, has somewhat misunderstood the procedure.

“Hey, Captain,” he shouts to Yaz in the clubhouse before the game, “they pump out your lunch this afternoon?” Yaz grins as Remy answers a make-believe phone call. “No, sorry, the captain’s not in now, he’s getting his lunch pumped out and his lungs pulled apart.”

As baseball appears to be a game of pauses, Yaz seems a man of silences. He begins most sentences with a silence, ends others that way; they may occur in midthought and last thirty seconds, but as in baseball, the pauses contain information. He forges a homely poetry from silences and bursts of speech. I ask about his son Mike, a switch-hitting outfielder in high school.

“I’ve heard your son is a hot prospect now.”

Yaz narrows his eyes. “A chance,” he says.

Unable to look interviewers in the face, he stares into his locker as if awaiting instructions from his uniform. He rubs his face as he ponders a question; his cheeks are flecked with white stubble, like grains of salt, and the skin of his neck is tucked into folds. The silence continues. Yaz seems to be contemplating the idea of “going down with class,” and one wonders if he knows the source of his great pride.

“It’s just something inside you. I always wanted to play, always knew I could play.” Silence.

In a time when many sports heroes seem to double as their own flacks, Carl Yastrzemski maintains the cool distance that gives birth to mystery. He comes by his reserve naturally. The son of a Bridgehampton, Long Island, potato farmer, he was raised in rural isolation, learning self-reliance early. And he was a physical child prodigy, a Mozart on the ball field. His father, Carl, Sr., saw the boy’s potential and put it to work, pitching to him until his hands were sore from hitting.

“Whenever we played stickball,” recalls Bill DePetris, a childhood friend, “Carl was the best, and he’d always pretend he was Ted Williams.” By the time he was 17, major league scouts were flocking to watch him play and filing delirious reports to their teams. “He had a beautiful, beautiful stroke,” says Frank “Bots” Nekola, the scout who eventually signed Yaz for the Red Sox, “almost like the stroke he has now. He had big hands from doing all that potato farming, and my God, he had such desire!”

Living close to New York, Yastrzemski at first hoped to play for the Yankees. They offered him a bonus of $40,000 to sign, but the figure was summarily rejected by his father, and Yaz ultimately signed with the Red Sox for $100,000. The size of the bonus earned him the nickname “Cash” from envious teammates.

Nekola remembers bringing his young prize to Fenway Park for the first time. He even recalls the date—November 28, 1958—and the story indicates something of Yastrzemski’s pride. “They drove up to Boston in the middle of this damn blizzard,” the scout says. “It was dismal, snowing like hell, and Fenway Park was the last place in the world you’d try to entice anybody with.” While Nekola waited nervously, the youngster trudged through the snow of the abandoned park. He studied the fences, then finally walked back to Nekola.

“I can hit in this ball park,” he said.

If you were a kid in the winter of 1960, and you longed for a touch of spring, you could pick up a baseball magazine and dream. You could read about a rookie touted by insiders to be the next summertime hero, and study the phonetic spelling of his name—“Say: YUH-STREM-SKI.”

The wall—known throughout the league as the “Green Monster”—looms 37 feet above the field, and Yaz catches balls off it with a pool shark’s eye for caroms.

By the age of 23, he was “Yaz,” a brash, power-hitting major league star. But despite his success, he fought with the Boston fans; sometimes they booed him even when he hit a home run. The Red Sox were a comic opera of a team, and the brilliant kid showed his disdain by loafing and sulking.

At the height of his war with the fans, Yastrzemski made a theater event of his disdain. As the booing mounted one day, he suddenly dropped his glove and dramatically extracted two wads of cotton from his ears.

Who changed—the fans or Yaz? “Yaz changed,” says Ken Harrelson. “Up until 1967, you’d see him dog it out there sometimes, not running out ground balls, going out of control emotionally.” Photos from that era show him to resemble a young Phil Spector—big shades, thin lips, a face that could be stamped Early Ulcer Candidate. “He’d sit in the clubhouse perfectly still, then get up and walk around in a crazy little circle, then sit back down again,” Harrelson says. “But in ’sixty-seven he got over the hump. He proved to himself that he could maintain control under pressure—the hell with the fans. It’s like a chain-smoker giving up cigarettes: Who else gives a shit? Nobody. But he does, and other people respond to the change in him.”

“The fans changed,” Yaz says. “They wanted me to be ‘the new Ted Williams,’ and I wanted to be myself. Fans in this town can go a little overboard.” A typical Yaz understatement—Boston fans rage, sputter and adore, filling the radio talk shows with an awesome volume of displaced passion. “But I changed, too. I started to realize that baseball was not a life-or-death matter.” This realization was deepened, he has said, by the recent death of his mother, and shows itself now as enhanced creativity on the field, a youthful exuberance.

Suddenly, a sun-weathered man of 59, his light step belying his thickening body, strides up to Yastrzemski’s locker. He cups Yaz’s head in his huge left hand and extends his right in greeting. It is Ted Williams, the finest hitter in baseball history and Yaz’s shadow-predecessor in left field for Boston.

Eighteen years ago today, in his final time at bat, Ted Williams homered off Baltimore’s Jack Fisher. Then he made way for Yastrzemski, with a prediction that the rawboned kid of 21 would be heir to the Williams greatness. It was a prophecy that sat like a curse on the young man’s head, blurring his own identity for years to come. “I never wanted to be the next Ted Williams,” Yaz often said, until he was sure he was perceived as himself. Now he smiles with delight at the old man’s touch.

“Jesus, Yaz,” Williams shouts as they shake warmly, “they got those old photos of you plastered up in the office, with your ears sticking out—you shouldn’t let them show ugly pictures like that.” Williams has flown to Boston from a New Brunswick fishing vacation, a rare visit, a gesture of support.

Yaz laughs off the insult and feigns sincerity, already preparing his response.

“Say Ted, was the sea pretty choppy up there? Get a lot of high water?”

“Oh, yeah,” says Williams, “real high. How’d you know?”

“Well, from looking at those pants,” says Yaz, pointing to the baggy gabardines that are too short by three inches, “I’d say you were expecting a flood!” The players in attendance erupt in laughter as Williams stares down wide-eyed at his cuffs. Yaz scans the room to catch appreciative nods for this verbal sucker punch—one of the few times he attempts eye contact. Obviously not an instinctive comic, he’s only accepted this patrimony of insult and jive recently, and he revels in each success he scores.

Williams, once legendary for his arrogance, tugs sheepishly at the lapels of his ill-fitting jacket.

“You wanna see class, Ted?” the captain asks, using the word so often used to describe both men. “Here’s class.” He reaches into his locker and grabs a pair of Levis worn down to a silky consistency. But Williams, once so graceful in uniform, still pulls awkwardly at his clothes.

“Dammit, Yaz,” he frowns, “now they’re gonna print that shit.”

That night, in Boston’s game with Detroit, Jim Rice hits a home run into the teeth of a north wind, and the Red Sox win, 1–0. Late in the game, with the tying run on base for Detroit, Yaz saves the victory by catching a fly ball off the wall and firing it to home plate before the runner can score. After he’s watched the play conclude, Yaz turns and stares at the spot where the ball hit, recording its angle of deflection in his mind.

“Playing the wall” is one of his specialities. The wall—known throughout the league as the “Green Monster”—looms 37 feet above the field, and Yaz catches balls off it with a pool shark’s eye for caroms. He knows every rivet, dead spot and bump, and stands there waiting for the ricochet, confident, his back to home plate. It’s one of the vivid images of the man, one reason why he’s known as the best left fielder in the game.

The Red Sox win, but the Yankees beat the Toronto Blue Jays, and Boston is “running out of space,” says manager Don Zimmer.

“We shouldn’t even be in this situation,” says George Scott, sitting naked on a stool after the game. “That lead, fourteen games—it went so damn quick, man.”

There are many theories for the Red Sox collapse. Yastrzemski holds the Injury Theory—seven of the nine Boston starters were hurt within the past month. Shortstop Rick Burleson, not widely regarded as a mystic, has begun to wonder if “fate” ordained the swoon. As usual, Bill Lee has a theory:

“There’s a religious element to it. The economic and corporate level of society works by one clock. Baseball and nature—which to me are synonymous—work on a different clock, without numbers. When you tamper with that natural clock, as the ownership of this club has done, you upset very delicate psychological rhythms. Look, the ivory-billed woodpecker eats the soft-backed grub in order to keep the pine tree healthy. When you introduce a pesticide you kill the grub, but you also kill the ivory-billed woodpecker and eventually the pine tree. The pesticide here is the practice of doing things solely for economic gain. And it’s too bad, because the Red Sox were a good pine tree.”

One doesn’t test such hypotheses on Carl Yastrzemski. But as the reporters gather around his locker, I ask him if, like Burleson, he believes in fate. He stares into his locker for 20 seconds.

“I believe,” he finally says, “in Cleveland scoring more runs than the Yankees.” He says it with a Gary Cooper terseness, then breaks into his incandescent smile.

A few moments later, his bronchitis acts up, and he fights to control a coughing jag. Twenty feet away, third-base coach Eddie Yost watches in concern. Yost, a scrubbed and avuncular man, represents an odd fact of baseball: In what other field do former workers, forcibly retired, haunt the places where they once knew youth? Yost’s playing career spanned 17 years, and as we discuss Yastrzemski’s age, I ask Yost how a ballplayer knows his time is up.

Yost sighs, still wistful, 16 years after the fact. “I’d hit a fly ball, and I knew it was a home run, knew I’d gotten all of it. But somehow it would be caught on the warning track.” The memory still hurts, and we shift back to Yaz. One doesn’t want to see him go out like Willie Mays, stumbling in the outfield, fooled by feeble pitches. “It won’t happen to Yaz,” Eddie Yost says. And I remember a conversation from the day before.

“To play two more years is very realistic,” Yastrzemski told me. “Three years is realistic if I have no major injuries. But I’ll know when my reflexes go, when I can’t get around on a fastball. Suddenly I’ll say to myself, ‘Shit, they’re gone.’ You have to be honest with yourself. Statistics are beside the point. Years I hit .290, I batted much better than years I hit .320. Line drives get caught, bloop hits fall in. With statistics, there’s luck involved. With reflexes, there’s no luck. I’ll let my reflexes tell me when to quit.”

And I think of something Ken Harrelson said: “Carl’s no great brainchild but he’s got a genius for exercising common sense.”

By Saturday, it is beginning to seem like a deathwatch on the Charles. Night after night, the Red Sox win, and the Yankees stay one game ahead; night after night, the crowd is like 30,000 rejected lovers sitting by the phone, waiting for a call they know won’t come. With each new run posted for the Yankees, the crowd essays a boo, but it comes out a wounded “oooh.” Despite the Red Sox resurgence, the fans seem dazed. In defeat, they had the solace of complete despair. Now, so achingly close, they root timidly, deprived of the chance to exult or vilify. The pressure shows as players snap at each other; only a handful of Red Sox escape the anxiety. Yaz sits in cut-off thermal underwear, nibbling at his lower lip. He is asked if the pressure is getting to him.

Silence.

“There shouldn’t be any pressure in a pennant race. You should enjoy it. My first six years here, I played on teams that finished thirty to forty games out of first place—that’s pressure. In a pennant race, you can play at a higher level, you can go beyond yourself. When you’re forty games out and make a great catch, who cares? It won’t have the same meaning. Nothing you can do will have much meaning. Knowing that is the worst pressure of all.”

Yastrzemski is the prototypical “money player,” wise in the mysteries of adrenaline, right at home in chaos. On the field, he shows no sign of feeling pressure; but sitting here, biting his lip, he seems in the grip of it. “I always feel tense right before a game—that’s the time to feel tense. When the game starts, I relax.” A few nights ago, in Toronto, reliever Balor Moore threw two fastballs at his head, sending him sprawling in the dirt. Then he got up and hit a triple.

“What did you feel the other night after you got knocked down?”

For a change, Yaz answers quickly.

“Nothin’. Just got up and kept looking for the slider.”

No emotion?

“No emotion. Maybe that’s because I never got hit bad. My reflexes bail me out.”

“He’s the only guy I know who, if you needed it—if you really needed it—could hit a six-run homer.”

Again, the torture: The Red Sox win, the Yankees win, and only a day remains. After the game, Bill Lee dresses slowly, weaving back and forth to a reggae tune. Butch Hobson, playing with constant agony from three bone chips in his elbow, massages the chips when he thinks no one is watching. And Luis Tiant… Luis Tiant is sweetly bizarre. Tomorrow he will pitch the last game of the regular season, the game on which everything depends, and today he is parading through the clubhouse dressed only in a blue vinyl pork-pie hat and ludicrous blue-denim boots, with a Havana clenched between his teeth. Like other costumes, a baseball uniform imposes certain stances on the wearer. Tiant, who on the field seems arrogant and menacing behind his Cuban Fu Manchu, is bald and pudgy and soft-voiced in the clubhouse. He promenades around as if his hat, boots and nudity were this year’s Paris look.

Now he’s confronted by Bob Stanley, the pitcher he called “ugly.” The quote has been picked up in a local paper, and Stanley mock-glowers at Tiant. Pouncing on the moment, Yaz instigates a conflict that Tiant sheepishly tries to resolve. “Hey man,” Tiant says to Stanley, “we was talkeen about you body, man, we was no talkeen about you face.” Yaz cracks up. This steady flow of insult is a form of massage, the players kneading each other’s psyches, with Yaz—nicknamed “Polack”—as the m.c. As the season ends, the clubhouse is a place of brief joys and black sulks; humor is a touchstone, a constant.

Yaz retreats to the trainer’s room for treatment. Carlton Fisk, playing with a cracked rib, spits tobacco juice into a tray of sawdust. Luis Tiant finishes dressing, fitting a blue shirt and blue pants between the boots and hat. Reaching into his locker, he extracts his last piece of apparel—it seems to be a nickel-plated .45-which he tucks into the waistband of his pants.

The last day of the deathwatch dawns gray and melancholy. This is the last game of the regular season: Unless the Yankees lose and the Sox win, Yaz will lose his chance to win a World Series. By now the phrase “World Champions” has become a mantra for him. (“The Yankees are playing like World Champions.” “If anyone had said at the beginning of the season we’d be this close to the World Champions, I’d have been happy.”)

Today, the Sox must beat the Toronto Blue Jays, an expansion team: Over that game they have control. But somehow the Indians must beat the Yankees, who loom as invincible as movie zombies.

All of Boston seems to be “playing the scoreboard”—watching the New York score as if a steady gaze could affect it. Until that lovely Fenway anachronism, the hand-operated scoreboard, declares a Yankee loss, the Red Sox can’t win the pennant. In the last few games, a people’s network has sprung up in the bleachers, where radio signals are clearest: Long before the reporters in the press box get the Yankee score, it’s been picked up on transistors and shouted from section to section, rows of people cheering or booing suddenly. Today, when the players arrive at the ball park, they find that the powers that control the scoreboard have not even posted the other games. Though a full schedule of contests will close out the season, in Fenway, there is only one Other Game.

“De-cision De-termines Des-tiny, fellas,” the preacher says, giving Sunday morning homily in an impromptu chapel—the equipment room of the visitors’ clubhouse. Bags of Louisville Sluggers, rolls of gauze and catcher’s mitts are piled high around him in tiers, as are the players’ suitcases, packed for the flight back to Toronto. A dozen young Blue Jays, looking quite like their namesakes, listen open-mouthed and wide-eyed to the locker-room evangelist. “Let me say that again—De-cision De-termines Des-tiny. Now boys, I don’t want to scare you, but we may have another Lyman Bostock in this room.” One blonde Jay seems ready to cry in fear at the mention of the recently murdered player. “I don’t mean to say that you’ll be shot as you leave the park. I just mean—we never know. And I’m just glad that two weeks before he passed, Lyman ordered my special cassette tape, explaining the New Testament, for just three dollars postpaid. I hope that the knowledge contained in that cassette, which comes with a personalized, pocket-sized edition of the New Testament, helped prepare Lyman for the afterlife into which he was so suddenly called. And if any of you boys would like this cassette with complementary New Testament, three dollars postpaid, you may let me know by simply lifting a finger as we now bow our heads to pray. De-cision De-termines Des-tiny.”

Out on the field, Yastrzemski stands in the batting cage, tamping down the dirt with his spikes, preparing to do whatever it takes. “Yaz is ready,” says Ken Harrelson. “He’s the only guy I know who, if you needed it—if you really needed it—could hit a six-run homer.” It’s an hour before game time as Yaz takes his swings, and right after he finishes, Toronto catcher Alan Ashby plays a cruel jape of youth on the 10,000 fans already in the park. Sneaking behind the manual scoreboard, he fiddles with the numbered plates, and when he steps away the score reads: CLEVELAND 8, NEW YORK 2. In reality that game has yet to begin. The crowd screams with joy, then lapses into sullen quiet as the truth becomes known.

But the Red Sox jump off to an early lead and, in the third inning, as Boston infielder Jack Brohamer settles under a Blue Jay pop fly, the people’s network sends out a joyful bulletin: four runs for Cleveland! Both games play themselves out to their natural conclusions and, magically, the Red Sox have forced a tie-breaker.

Afterward, in the clubhouse, the players whoop it up as they peel off layers of underwear. Yaz splashes beer on teammates in the shower. Reporters struggle to pick out recognizable words from Luis Tiant’s discourse: “We play for pride,” he says, smoking a Kool and chewing a wad of tobacco. “People say we choke. We cho’ dem we don’ choke. If we don’ win today, ain’ no more. Losers don’ go nowheres.” In general, the reporters ask idiotic questions. Did you feel the pressure? Were you happy to be pitching? Baseball is too mystical to be codified in words.

The Red Sox threw music at the Blue Jays this weekend. Dennis Eckersley, in winning his 20th game yesterday, performed like a rock-and-roll pitcher—all fastballs, sweat-drenched hair and wild flourishes. And Tiant, who makes the simple act of releasing the ball into a shell game, throwing shoulders and elbows and feet everywhere, seemed like a salsa pitcher. (“I’d say a rhumba pitcher,” Bill Lee says.) The Blue Jays were easy game for both men, the Indians justified Yastrzemski’s faith, and now the Yankees and Red Sox must duke it out face to face.

Yaz emerges from the shower to face more pointless questions. He is smiling.

The tie-breaker, only the second in American League history (the first was in 1948), has the aura of a heavyweight fight. As the Red Sox take batting practice, reserve Yankee catcher Cliff Johnson saunters over to kibitz with George Scott, who stands in the cage.

“Yo, George.”

“Hapnin’, Cliff,” Scott grunts as he swings. He does not look at Johnson, who seems bemused.

“Ain’t you talkin’ to me today, George?”

“No, Cliff,” says Scott, lining a shot off the wall. “I’m serious today.”

Moments later, Mickey Rivers stands watching Yaz take his cuts. The jive-talking center fielder is as far removed from Yaz as possible, yet he watches in fascination. Suddenly, a Yankee outfielder, Gary Thomasson, walks up to Rivers.

“Hey, pimp.”

Rivers turns around. “Pardon me, dickhead, can I help you?”

“Pimp, I’m digging a pool back home. After I saw the Red Sox score yesterday, I got on the phone and hollered, ‘Stop digging!’ Now I don’t know if I can afford it.”

“Don’t worry, dickhead,” Rivers assures him. “You’ll be able to keep diggin’ after today.”

Thirty-three thousand people rise, applauding, as Yaz comes to bat in the second inning. He’s facing the best pitcher in baseball, left-hander Ron Guidry, who has only surrendered one home run to a left-handed hitter all season. Yaz finds his balance, hoists the bat, squints out at Guidry. He gets an inside fast-ball and cracks it to right field—the ball rises, curves and hooks just inside the foul pole for a home run. He trots around the bases and returns to the dugout, where he’s mobbed by teammates.

He’d been expecting the pitch. Yastrzemski is a modified “guess hitter,” which means he anticipates a slider or fastball or curve and tailors his swing to meet it. Before the game, someone asked Yaz about guess hitting and he smiled. “I’m a think hitter,” he said. And he’d just thought a home run into being.

The home crowd senses victory—you can tell because they start chanting “Yankees suck!”—but in the seventh, Yankee shortstop Bucky Dent strokes a three-run homer, and in the eighth, the hated Reggie hits a solo shot. Yaz counters in the bottom of the inning with a single, knocking in his second run of the game.

Then comes the ninth inning, the stuff of pulp epics. Down one run, the Red Sox have men on first and second with one out. As slugger Jim Rice steps up to bat, the crowd generates a Concorde roar. Yaz kneels in the on-deck circle, sifting dirt through gloved hands, studying the pitcher’s motion, the sunny green field, the way the flag rustles softly in the wind.

“Just as I swung, the ball tailed in on me. It was a hell of a pitch….” He sighs again, crying lightly now, and stares up at the ceiling, a 39-year-old man.

The roar turns inside out, becoming a moan as Rice lifts a fly ball deep to right for the second out; then it evolves into a roar again as Yaz approaches the plate. In his mind, though, he hears only silence. “Total silence. Me and the pitcher. The crowd may be cheering or booing, for me it’s as if they’re not there. I analyze the situation, the pitcher’s strengths, what he’s likely to show me, and I concentrate.” Carl Yastrzemski has come to bat more than 12,000 times in his career. To him, this is the most crucial time of all.

He walks slowly up to home plate with a pigeontoed stride, then bends at the waist and scoops up more dirt, weighing it with a contemplative air. Digging the spikes of his back shoe into the chalk edge of the batter’s box, he shifts his weight from foot to foot, searching for the elusive balance, measuring home plate with his bat. When he’s settled, he twirls his Louisville Slugger, 32 ounces of white ash, lightly, slowly. Rich Gossage, a powerful but erratic relief pitcher, raises his arm to deliver the ball.

“I saw a hole between the first baseman and second baseman,” Yastrzemski says later, “and I wanted to drive a ground ball through it. I was looking for a fastball inside, and he threw it, knee-high and in. As it came towards me, I thought, ‘This is what I wanted.’ ” The roaring fans are dead certain that Yaz, the greatest clutch hitter in baseball, will come through once again.

But something happens that Carl Yastrzemski, who has made a calculus of hitting, has not reckoned on. As he swings, the ball—moving at 95 miles per hour—swerves in suddenly toward his wrists. Instead of the desired hard single to right field, he pops up weakly to third base, where Graig Nettles catches it for the last out. The crowd remains standing, eerily silent, as Yastrzemski trudges back to the dugout, his summer over.

Afterward, in the hushed clubhouse, Yaz stands red-eyed under the lights, enduring an ordeal by interview. A reporter asks about the pitch he popped up.

“Just as I swung, the ball tailed in on me. It was a hell of a pitch….” He sighs again, crying lightly now, and stares up at the ceiling, a 39-year-old man. “I just wish it hadn’t tailed in. Gossage’s fastball is unpredictable, sometimes it tails away. This one”—a long pause—“tailed in. But you can’t be cautious. You swing with one idea in mind. Aaah… You wonder if it was meant to be.”

By the time he finishes answering questions, other players are saying good-bye for the year. From Yaz’s locker you pick up wisps of his speech: “They played like World Champions…. This is a great bunch of guys…. Next year, we’re going to win it.” In flannel shirts and jeans and boots, the players are now only men. Bob Stanley, the butt of the “ugly” joke, elbows his way through a crowd to say goodbye to George Scott. Stanley gave up the winning home run to Reggie Jackson, and now he’s going home.

“See you next year, George, somewhere,” he calls.

“Oh, ah’ll be here, Bobby,” Scott nods. “Ah see you here, don’ worry ’bout that.”

Bill Lee walks out of the Red Sox clubhouse, probably for the last time. (He has been feuding with management and will likely be traded.) He’s carrying his glove—with a copy of Dune, the science-fiction novel, tucked into the webbing. He walks past the line of suitcases, packed for a trip to the play-offs in Kansas City, which now won’t go there. “Does this mean we’re not going anywhere?” he says to no one in particular.

Yastrzemski will mourn the Last Out for a while. Soon, though, he’ll be fishing the waters off Boca Raton, and late in the winter, he’ll begin working out with a weighted bat, swinging it hundreds of times a day. One hopes he’ll remember his own words of a few days ago: “You don’t always make an out. Sometimes the pitcher gets you out.”

Next March he’ll report to camp, ready to begin spring training, nearly 40.

[Featured Image: Sam Woolley/GMG]