On a warm afternoon earlier this fall, Harry Dean Stanton, wearing an old denim work shirt, Levis, and deck shoes, sat on the sofa of his Mullholland Drive home high above Los Angeles dispensing shopping instructions to a female assistant regarding the purchase of a present for his maid. “Get Maria something nice,” Stanton said. “Spend $200, $300. She works so hard.” Then, in a nearly incredulous tone, the 60-year-old actor added, “I’m not rich, but for the first time in my life I have money.”

Grizzled and lean, with a face dominated by hollowed cheeks and deep-socketed brown eyes, Stanton possesses the hungry look of a man who knows about living on the run. No surprise that he has usually played tough guys, psychopaths, and criminals. Somewhere along the way, he even began to live like a marginal character. His house, a small wooden structure that clings to a hillside overlooking the San Fernando Valley, is the epitome of a disheveled bachelor pad.

The bedroom contains a mattress on the floor and not much else. Save for a beer or two, the kitchen refrigerator is usually empty. In these Spartan quarters Stanton—despite all evidence to the contrary—long nurtured the hope that film directors would see him as more than just an onscreen slasher.

After giving his assistant her marching orders, Stanton slipped on a pair of half frame reading glasses and in a pile of bills and magazines located the script for Beth Henley’s Crimes of the Heart, a movie he had turned down.

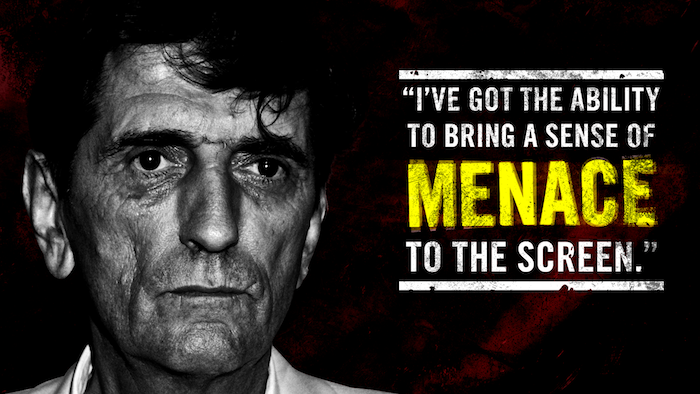

“They wanted me to play a corrupt Southern senator,” Stanton said. “I could have really scored with it, but I would have been a heavy. There’s a scene where the character they wanted me to do kicks the hell out of a black kid, and that’s why I didn’t take it. The role is superbly written, but it’s gotten debilitating over the years to have people say to me, ‘You’re the bad one. You’re the one who gets shot.’ Give me a break for a change. I know I’ve got the ability to bring a sense of menace to the screen. I have that specific competence, and it’s kept me working. But I don’t want to do anything else that’s life negative.”

Standing up, Stanton walked to the fireplace. Outside, it was 85 degrees, but a blaze was roaring on the hearth. “It’s for company,” he said. For several minutes, he stared into the flames.

It is all now finally beginning to change for Harry Dean Stanton. After an apprenticeship of nearly three decades, he is no longer numbered among Hollywood’s character actors, those hard-working cogs whose faces and roles are more memorable than their names. With anonymity only a bad memory, he has just completed work on Slam Dance, in which he plays opposite Tom Hulce, and John Sayles is talking to him about starring in his next film. Earlier this year, a trio of movies featuring him opened almost simultaneously.

In Robert Altman’s Fool for Love, Stanton is the deranged, ornery, but ultimately benevolent “Old Man,” father to both Sam Shepard and Kim Basinger. In Pretty in Pink, he plays Molly Ringwald’s dad. In an episode of Showtime’s Faerie Tale Theater directed by Francis Ford Coppola, he is that most innocent of American folk heroes—Rip Van Winkle. These were quickly followed by Disney’s One Magic Christmas, in which the actor portrays an angel named Gideon.

Recently, celebrity has also come to Stanton in other ways—his friendships with such members of the well-publicized “brat pack” as Madonna and Sean Penn, several appearances on Late Night with David Letterman, and even a gig as guest host of Saturday Night Live, where instead of delivering the traditional opening monologue, he belted out a blues number with the house band.

“There was such a long period in my life in which I was struggling to bloom, and as a result I did a lot of stupid things.”

Stanton’s rise is unusual for his breed of actor. Supporting performers do not ordinarily attract powerful agents or managers, nor can they afford to throw high-visibility parties. They must audition several times a week, thus living with constant rejection. Their pay may range up to $25,000 per picture, but when they do get a break, they are usually cast in the same sort of generic roles—mothers, the hero’s best friend, or small-time villains. Most character actors are stuck in such niches for life.

Prior to 1983, the year things started to turn around for Stanton, his 50 or so film credits read more like a rap sheet than a resume. After breaking into the movies in a 1957 western, he was picked the following year to play a bad guy opposite Alan Ladd in The Proud Rebel, and the type was cast. What followed was a cinematic crime spree— films like Hostage, Day of the Evil Gun, and so on. During the 1960s there was no respite in his television work—in each guest spot he reprised a version of the violent persona that provided his bread and butter.

Occasionally, Stanton rose up out of his rut to deliver gemlike performances that revealed greater depths. In The Missouri Breaks, he was winning and dignified as the co-leader of a gang of horse thieves on the lam from Marlon Brando. In Cool Hand Luke, he was the sweet and melancholy convict who serenades Paul Newman with gospel music. In The Godfather, Part II, he played the taciturn F.B.I. agent assigned to guard Frankie Pentangeli.

The turning point for Stanton was Wim Wenders’s film Paris, Texas, winner of the 1984 Grand Prize at the Cannes Film Festival and the first movie in which Stanton, after 27 years in the business, was cast as the leading man. When Stanton talks about the picture his voice takes on hushed tones. “That opening scene parallels my own personal quest for the grail, as it were,” he observed recently.

Paris, Texas begins out on the parched Southwestern badlands. To the eerie strains of Ry Cooder’s guitar soundtrack, a solitary figure marches resolutely toward some unknown destination. The face is that of a man who has been deeply wounded, and it belongs, of course, to Harry Dean in the role of Travis.

The film ends with Travis’s rejuvenation. After a reunion with his brother and son, he musters the courage to visit his estranged wife (Nastassja Kinski). Their encounters are heartbreaking, and Stanton gives a wrenching performance as a character working through the debris of his life to arrive at the strength and resolution to quit running and begin again.

Stanton got this breakthrough part because Sam Shepard, author of Paris, Texas, looked across a barroom in Santa Fe, New Mexico, one evening in 1983. The place was thronged with people attending a film festival, and Shepard’s eyes fell upon Harry Dean. Over shot glasses of tequila, the playwright-actor and the character actor fell into conversation.

“I was telling him I was sick of the roles I was playing,” Stanton recalled. “I told him I wanted to play something of some beauty or sensitivity. I had no inkling he was considering me for the lead in his movie.”

Not long after Stanton returned to Los Angeles, he picked up the telephone to hear Shepard offering him the part. “My first question was, ‘Why aren’t you doing it?’” Stanton said. “Sam replied that it was too indulgent, and besides, he was also doing Country at the time. So I said yes.”

When Harry Dean Stanton arrived in Hollywood during the 1950’s, he was convinced that within a couple of years he’d become a star. His optimism, however, was undercut by the insecurities and frustrations he’d carried with him since childhood.

Stanton was born in the little town of West Irvine, Kentucky, into a troubled family. His mother and father were constantly separating. During the worst years of the Depression, the brood moved frequently. Often, Harry Dean felt as if there were no place he belonged. Whatever solace he drew from his parents’ strict, Southern Baptist faith evaporated as he began to sense that fundamentalism was anathema to his rebellious spirit.

When he was upset during boyhood, Harry Dean sang about his woes. If the house was empty, he’d climb atop a stool in the kitchen and practice the songs. He was about 8 when he started such performances.

“One day I just got up and started singing ‘T for Texas, T for Tennessee, T for that girl who made a wreck out of me,’” he offered not long ago. “I guess you could say that was the birth of my blues, but it’s also when I went into show biz.”

Stanton, however, never seriously considered acting until he was in college. Following a tour of duty in the Navy during World War II, where he served on an LST in the Pacific and received a commendation for coolness under fire, he entered the University of Kentucky. During his junior year, he settled on a major in drama after a successful campus production. But he quit school without graduating.

“I made it a point not to graduate,” Stanton said. “I thought that was a positive, independent kind of statement. I never liked being ordered around—which, of course, was an overreaction. I eventually found out that I didn’t mind being ordered around at all when it was by someone who knew what he was doing.”

After an interval as a student at the Pasadena Playhouse in California, Stanton joined the American Male Chorus on a national tour (he also drove the bus). Then he moved to New York and signed on to the road company of the Strawbridge children’s theater. Soon he was back on the highways. By 1957, when he’d had his fill of touring, he settled on the West Coast for good and began his long run as a movie bad guy.

Harry Dean Stanton’s friend Fred Roos, a producer and casting agent, remembers that throughout the 1960s, “Harry always had so much hostility and resentment. There was a long period when he couldn’t get anything but bit parts, and the frustration level was extremely high. You read interviews with other character actors, and they’re proud of their work, proud of being able to bring a touch of authenticity to a small part. But not Harry. He kept saying, ‘I have to get out of this.’”

From the perspective provided by his newfound good fortune, Stanton said recently, “I don’t blame anyone but myself for the kind of parts I got. To blame external circumstances is absolute folly. I hated being typecast in those roles. It was personally limiting, only playing stereotyped heavies. But I got those roles because I was angry, because that’s what I projected. I was angry at my mother and father because they didn’t get along, angry at the church. On top of that, I had an extreme lack of self-confidence.”

During his early years in Hollywood, Stanton had numerous brief entanglements with women, none lasting much longer than a year. “I was troubled by all the life problems—finding a mate, having a family, settling down. I just couldn’t get those things right.” Stanton’s longest-lasting relationship was with a young actress, Rebecca de Mornay. However, it ended badly, too. Ultimately, Stanton began to develop the Beat-era persona of a man living on the edge of reality. He was mercurial, nocturnal, and often unconscious. He had a knack for making improbable statements and winding up in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Jack Nicholson, who roomed with Stanton in a house in the Hollywood Hills during the early 1960s when both men were scrounging for small character parts, came to regard Harry Dean as “one of the truly unpredictable entities on the planet.”

“I just couldn’t stand the idea of getting killed by a man in a dress.”

At his worst, Nicholson said, Stanton “could drive people crazy.” For example, during the filming of Pat Garrett and Bill the Kid, Stanton ruined an expensive shot by accidentally jogging across a set while cameras were rolling. Kris Kristofferson, the film’s star and one of Stanton’s old friends, recalled that the movie’s director, Sam Peckinpah, “had waited all day just to get this one shot right in which James Coburn rides off into the early-morning light after killing me. Peckinpah was furious. He yelled at Harry, ‘You just cost me $25,000.’ Then he picked up a bowie knife and threw it at him. It was a pretty close call.”

At his best, however, Stanton was not awed by Hollywood’s biggest stars. “On the set of The Missouri Breaks,” Nicholson was saying not long ago, “I saw Harry Dean make one of the bravest and most inspired moves I’ve ever had the chance to witness. You remember that Brando wore a dress in that picture. It was all in keeping with his character, a deranged lawman chasing me and Harry. On the day he was finally supposed to kill Harry—it was awful; he was supposed to impale him on this stake—Marlon briefly turned his back, and Harry snuck up on him, jumped on top of him, and ripped off the dress. Now, I have a singular admiration for that event. Marlon knew what an honest thing Harry was doing. The whole time Harry was wrestling him down, he was smiling.”

The only thing Stanton cared to say about the episode with Brando was, “I just couldn’t stand the idea of getting killed by a man in a dress.”

Although Stanton is proud of his distaste for artifice and his refusal to be bound by convention, he’s a little sheepish about his reputation. “I sure wish I’d matured earlier,” he said recently. “There was such a long period in my life in which I was struggling to bloom, and as a result I did a lot of stupid things. I’d say that I’m now a lot more stable. I was just a very late bloomer. It was Eastern mysticism that began to help me. Alan Watts’s books on Zen Buddhism were a very strong influence. Taoism and Lao-tse, I read much of, along with the works of Krishnamurti. And I studied tai chi, the martial art, which is all about centering oneself.”

But it was The I Ching (The Book of Changes) in which Stanton found most of his strength. By his bedside he keeps a bundle of sticks wrapped in blue ribbon. Several times every week, he throws them (or a handful of coins) and then turns to the book to search out the meaning of the pattern they made. “I throw them whenever I need input,” he said. “It’s an addendum to my subconscious.” He now does this before almost everything he undertakes—interviews, films, meetings. “It has sustained and nourished me,” he said. “But I’m not qualified to expound on it.”

Stanton contends that his quest for self-awareness has given him the courage “to begin the next phase of my career.” In fact, he suggests, “I’ve only started getting good parts because I’ve changed, because I’m no longer so angry. I’m much more confident now, and it comes through.”

Still, Harry Dean Stanton has retained just enough of his rambunctious, childlike self to have grown into a peculiarly complex man—part tyro, part tough, and part teacher. “Harry Dean has got a rebelliousness in him, a freedom, a youthfulness, that even most young people don’t have,” commented Madonna. “At the same time he has the wisdom of the ages, an Eastern philosophical point of view.” In other words, Stanton is 60 going on 22, a seeker who also likes to drive fast cars, dance all night, and chain-smoke cigarettes with the defiant air of a hood hanging out in the high school boy’s room.

Although Stanton abhors the term brat pack—“It’s just a handle for the media, and it confines everyone to the kiddy table when a couple of these people are way beyond that”—he regards several of the young stars grouped under the heading as his best friends.

The attraction, which is mutual, grew out of his work in the title role of the cult-classic Repo Man in 1983. A hard, nihilistic film set in a sterile California suburb—a place where all the products are packaged in plain wrap, burned-out hippie parents sit comatose in front of TV preachers, and most folks can’t keep up with their car payments—the movie limns the desperation experienced by teenagers who see no place for themselves in the modern world. When one such teenager (played by Emilio Estevez) goes to work for a car repossession agency, Stanton instructs him in the art of legally stealing automobiles. More important, Stanton imbues the boy with what he calls “the Repo code,” a set of commandments for an unglued society: “Repo man don’t go running to the law; Repo man goes it alone; Repo man would rather die on his feet than live on his knees.” When Stanton is shot down by the police at the film’s conclusion, he is seen as a martyr.

Stanton’s role in Repo Man elevated him to the position of punk icon, and thereafter he became one of the few Hollywood old-timers easily embraced by young actors, particularly Sean Penn.

Penn, perhaps the most accomplished and surely the most outrageous of the movie’s new stalwarts, sat down beside Stanton one night at On The Rox, a private West Hollywood club, where the two quickly struck up a friendship. “It was just one of those things where I met someone I really liked,” said Penn. “He’s a good companion, and he could keep up drinking with me all night. After we met, we went to France together for the Cannes Film Festival where Paris, Texas won the prize. Then we spent a week in New York hanging out. The amazing thing about him is that unlike most older guys he treats you like an equal. I think this is because he’s so adaptable himself. Behind that rugged old cowboy face, he’s simultaneously a man, a child, a woman—he just has this full range of emotions I really like. He’s a very impressive soul more than he is a mind, and I find that attractive.”

Penn was so taken with Stanton that he and his soon-to-be wife Madonna began going out with the older actor almost weekly. Now, the three of them— often accompanied by Sean’s parents—spend many evenings together eating dinner, attending the movies, or dancing. Stanton is so fond of Penn and his connections that he’s come to see them as his surrogate family. He calls Sean and Madonna “the kids.”

Similarly, Penn and Madonna feel a strong family tie to Harry Dean. “I know he’s lonely sometimes,” said Madonna, “but I think he’s reconciled himself to being a lone figure in the universe.”

Nowadays, Harry Dean Stanton shows signs of channeling his self-exploration toward becoming the kind of actor remembered for his artistry. His conversations are peppered with words like “good taste,” “quality,” and “significance.” He seeks rolls that are “righteous,” using the word in its street connotation to mean “serious and profound.” What he wants is that one magic part, the one they’ll mention in film dictionaries, that will finally make up for all the awful parts from early in his career.

“The role for Harry Dean really is still out there,” said his old friend Fred Roos. “I’ve been in his corner so long that I’d like to be the one to give it to him, so I’m looking waiting.”

The danger in the tack Stanton has taken is that he may become so selective that producers and directors will regard him as a prima donna. “I think Harry Dean’s a victim,” said Robert Altman. “He’s 60, and he’s been doing this all his life, and now he wants adulation and respect. He’s so thirsty for it. Not only does he want the acclaim, but he wants the things that our industry uses to confer worth—more money, a bigger makeup trailer. As much as I wanted him in Fool for Love, he almost didn’t get the part because his agent was gouging us for these things, making outrageous demands. I hope Harry Dean gets beyond this.”

Stanton, however, is willing to take the chance of alienating Hollywood’s powers because for so many years he feels that he did exactly what he was told and it got him nowhere. “Life is very short, and I have to take advantage of the chance I now have,” he said one evening at dinner at City Restaurant, a hot, new Hollywood dining spot.

Stanton was seated at a good table, and from time to time other patrons glanced over, recognizing that a star was in their midst. It was a new sensation for Harry Dean—something that rarely happens to a character actor—and he liked it. Buoyed by the attention, he said, “I don’t really want a career right now. What I want to do is what is artistically right, to make an impact.”

Stanton, for so many years the touch of evil in film after film, looked across the table and added: “Well, there is one part I really want to play, but it hasn’t been written yet, although some people are talking about it. I want to play Henry Clay, the man who held the Union together for so long before the Civil War. I want to play him because he’s credited with the line, ‘I’d rather be right than be President.’”

It all seemed so improbable yet so apt. Clay, like Stanton, was a Kentuckian. He also had a weathered face, but he is remembered for his noble aspirations. After playing so many men with weathered faces and ignoble desires, it was hard to blame Harry Dean Stanton for dreaming of finishing his acting career not as a sinner but as a saint.

This story is collected in A Man’s World.

[Illustration by Sam Woolley]